The Actual Characteristics of the Dec Ian Persecution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Ottobre: SAN FRANCESCO D'assisi

Ottobre-Dicembre.qxp_Layout 1 07/12/18 11:29 Pagina 1 Santini e Santità Notiziario A.I.C.I.S. n. 4/2018, Ottobre-Dicembre 4 Ottobre: SAN FRANCESCO D’ASSISI Ottobre-Dicembre.qxp_Layout 1 07/12/18 11:29 Pagina 2 Notiziario A.I.C.I.S. n. 4-2018, Ottobre - Dicembre dell’Associazione Italiana Cultori Immaginette Sacre, fondata da Gennaro Angiolino il 6 luglio 1983 Sommario 3 Vita Associativa Renzo Manfè 4 Maria Madre della Chiesa Attilio Gardini 6 La magia dall’impronta del Cristo Veronica Piraccini 7 Mostre di santini Renzo Manfè 11 Santi, Beati e Servi di Dio in immagini Vittorio Casale 12 5.7.2018: Prom.ne Decreti della Congr. Cause dei Santi Renzo Manfè 13 Prolusione in occasione dell’Apertura dello Studium 2018 Card. Angelo Amato 16 Mostra Aicis sul santino natalizio 2018 Renzo Manfè 17 Cerimonie di Beatificazione e canonizzazione nel mondo Renzo Manfè 18 Notizie dal mondo Renzo Manfè 19 I Santini Orientali Maria Grazia Reami O. 28 Lungo i sentieri del Fondatore dell’Aicis: Gennaro Angiolino Attilio Gardini 29 Ss.Patroni di Regioni e Province italiane 7ª Regione: Lombardia, 1ª parte Giancarlo Gualtieri 32 Manifesto Mostra sociale Aicis “In dulci Jubilo” Daniele Pennisi Ufficio di Redazione: Via Merulana 137 - 00185 Roma In copertina: San Francesco d’Assisi DIRETTORE RESPONSABILE: Mario Giunco (4 ottobre) REDAZIONE: R. Manfè, G. Gualtieri, A. Mennonna, G. Zucco, A. Cottone Incisione della prima metà del COLLABORATORI di questo numero: Amato Card. Angelo, V. Casale, A. Gardini, 1800 di area praghese con ac- G. Gualtieri, R.Manfè, D. -

Dublin Jerome School Profile

Dublin City Schools Dublin Jerome High School 8300 Hyland Croy Road • Dublin, Ohio 43016 614-873-7377 • 614-873-1937 Fax • http://dublinjerome.net Principal: Dr. Dustin Miller CEEB: 365076 School & District Dublin is a rapidly growing, upper-middle class, suburban, residential community located northwest of Columbus, Ohio. The majority of the residents are professional and business people employed in Columbus. Dublin Jerome High School is a four-year high school, with an enrollment of 1,580 students in grades 9-12. This 2015-16 school year is the twelfth year for DJHS, which anticipates a graduating class of 370 students. Dublin Jerome is fully accredited by both the State of Ohio Department of Education and North Central Association of Secondary Schools and Colleges. Jerome High School has 120 certificated staff. Of these, 90 have a master’s degree. Counseling Staff & Ratio Mrs. Lisa Bauer 9th-12th A-E Mrs. Jennifer Rodgers 9th-12th F-K Mr. Aaron Bauer 9th-12th L-Rh Mr. Andy Zweizig 9th-12th Ri-Z Mrs. Karen Kendall-Sperry 9th-12th A-Z Enrichment Specialist Graduation Requirements The curriculum at Dublin Jerome is comprehensive, including Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate, honors, occupational, vocational and adjusted programs. Twenty-one units of credit are required for graduation. Specific requirements include 5 elective courses and the following: 4 units English 4 units Math 1/2 unit Health 1 unit Fine Arts 3 units Social Studies 3 units Science 1/2 unit Phys. Ed. Honors / Advanced Placement Honors opportunities are available in English I, II, III, College Composition I, College Composition II, Algebra II, Geometry, Precalculus, Spanish IV and V, Latin Poetry or Latin Literature, and Japanese IV. -

Ulivo 2007-1.Indd

l’Ulivo Nuova serie • Anno XXXVII Gennaio-Giugno 2007 - N. 1 3 Editoriale Texte francais, p. 5 – English text, p. 7 – Texto español, p. 9 Articoli 11 PAOLO MARIA GIONTA La mistica cristiana 54 MICHELE FONTANA La Parola efficace nella mediazione della Chiesa 81 RÉGINALD GRÉGOIRE Le congregazioni di fine medioevo e la nascita del monachesimo moderno con il Concilio di Trento (1545-1562) 100 CHRISTIAN A. ALMADA, Anselmo d’Aosta nella “storia-monastico-effettiva”. Il suo posto nella storia del pensiero sulla scia di H. U. von Balthasar, R.W. Southern e J. Leclercq 121 DONATO GIORDANO, Le prospettive dell’ecumenismo e del dialogo in Italia 134 ENRICO MARIANI Il “Ristretto compendio” delle Costituzioni olivetane 169 BERNARDO FRANCESCO GIANNI, «La città dagli ardenti desideri». Mario Luzi custode e cantore della civitas 221 HANS HONNACKER, «Siamo qui per questo ...». Mario Luzi a San Miniato al Monte Vita della famiglia monastica di Monte Oliveto 231 ILDEBRANDO WEHBÉ D. Miniato Tognetti, un profilo biografico Indicazioni bibliografiche 244 Recensioni e segnalazioni 254 Bibliografia olivetana 2 EDITORIALE In coerenza col nostro umile ma appassionato servizio alla memoria e alla traditio del patrimonio umano e spirituale della famiglia mona- stica di Monte Oliveto, inauguriamo in questo numero dell’Ulivo una nuova sezione della rivista interamente dedicata alla pubblicazione di immagini fotografiche, quale espressione documentaria e non di rado anche artistica in grado di custodire e veicolare aspetti, protagonisti e momenti della nostra storia monastica. Un sorta di album si incariche- rà infatti di raccogliere, principalmente col contributo degli archivi di tutti i monasteri della nostra Congregazione, un’antologia di immagi- ni che, organizzata tematicamente, contribuirà non solo ad arricchire le nostre conoscenze, ma anche ad incentivare nelle singole comunità la valorizzazione, mediante un’adeguata raccolta e catalogazione, del patrimonio fotografico posseduto. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St

NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome About NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome Title: NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.html Author(s): Jerome, St. Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) (Editor) Freemantle, M.A., The Hon. W.H. (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Print Basis: New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892 Source: Logos Inc. Rights: Public Domain Status: This volume has been carefully proofread and corrected. CCEL Subjects: All; Proofed; Early Church; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. Fathers of the Church, etc. NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome St. Jerome Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page.. p. 1 Title Page.. p. 2 Translator©s Preface.. p. 3 Prolegomena to Jerome.. p. 4 Introductory.. p. 4 Contemporary History.. p. 4 Life of Jerome.. p. 10 The Writings of Jerome.. p. 22 Estimate of the Scope and Value of Jerome©s Writings.. p. 26 Character and Influence of Jerome.. p. 32 Chronological Tables of the Life and Times of St. Jerome A.D. 345-420.. p. 33 The Letters of St. Jerome.. p. 40 To Innocent.. p. 40 To Theodosius and the Rest of the Anchorites.. p. 44 To Rufinus the Monk.. p. 44 To Florentius.. p. 48 To Florentius.. p. 49 To Julian, a Deacon of Antioch.. p. 50 To Chromatius, Jovinus, and Eusebius.. p. 51 To Niceas, Sub-Deacon of Aquileia. -

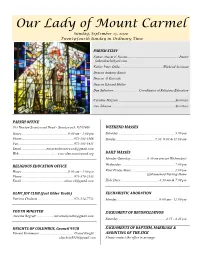

September 13, 2020 Twenty-Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time

Our Lady of Mount Carmel Sunday, September 13, 2020 Twenty-fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time PARISH STAFF Father Abuchi F. Nwosu ............................................................ Pastor [email protected] Father Peter Oddo .................................................. Weekend Assistant Deacon Anthony Barile Deacon Al Kucinski Deacon Edward Muller Dan Salvatore ............................. Coordinator of Religious Education Caroline Mazzola .................................................................. Secretary Ann Johnson .......................................................................... Secretary PARISH OFFICE 203 Newton-Swartswood Road • Swartswood, NJ 07860 WEEKEND MASSES Hours ...................................................... 9:00 am - 1:00 pm Saturday ................................................................. 5:00 pm Phone ............................................................. 973-383-3566 Sunday ............................................. 7:30, 9:00 & 11:00 am FaX ................................................................. 973-383-3831 Email ............................. [email protected] Web ............................................ www.olmcswartswood.org DAILY MASSES Monday-Saturday ................... 8:30 am (except Wednesday) RELIGIOUS EDUCATION OFFICE Wednesday .............................................................. 7:00 pm Hours ...................................................... 9:00 am - 1:00 pm First Friday Mass .................................................. -

The Life and Death of Sir Thomas More, Knight by Nicholas Harpsfield

The Life and Death of Sir Thomas More, Knight by Nicholas Harpsfield icholas Harpsfield (1519–1575) com- Clements, and the Rastells. With Mary’s ac- Npleted this biography ca. 1557, during cession to the throne in 1553, he returned and the reign of Queen Mary, but it was not pub- became archdeacon of Canterbury and worked lished until 1932. Indebted to William Rop- closely with Cardinal Reginald Pole, the Arch- er’s recollections, Harpsfield’s Life presents bishop of Canterbury. With Mary’s and Pole’s More as both a spiritual and secular figure, and deaths in 1558, and with his refusal to take the Harpsfield dedicates his biography to William oath recognizing Queen Elizabeth’s suprem- Roper, presenting More as the first English acy, Harpsfield was imprisoned from 1559 to martyr among the laity, who serves as an “am- 1574 in Fleet Prison where, as he relates in his bassador” and “messenger” to them. Dedicatory Epistle, William Roper supported Harpsfield was born in London, and was ed- him generously. ucated at Winchester and then New College This edition of Harpsfield’s Life is based on at Oxford where he became a perpetual fellow the critical edition published for the Early En- and eventually earned a doctorate in canon glish Text Society (EETS) in 1932 by Oxford law. In 1550, during the reign of Edward VI, University Press, edited by E. V. Hitchcock; he moved to Louvain and come to know many the cross-references in the headnotes refer to in the More circle such as Antonio Bonvisi, the this edition. -

Church “Fathers”: Polycarp

Church History and Evidences Notes: Church “Fathers”: Polycarp I.Church “fathers” and their writings: Polycarp A. Polycarp of Smyrna 1. Polycarp of Smyrna (c. 69 – c. 155) was a Christian bishop of Smyrna (now İzmir in Turkey). 2. According to Eusebius (260-340AD) supposedly quoting Irenaeus (130- 202AD), Polycrates of Ephesus (130-196AD) cited the example of Polycarp in defense of local practices during the Quartodeciman Controversy. Polycarp supposedly tried and failed to persuade Pope Anicetus to have the West celebrate Passover on the 14th of Nisan, as in the Eastern calendar. 3. Around A.D. 155, the Smyrnans of his town demanded Polycarp's execution as a Christian, and he died a martyr. The story of his martyrdom describes how the fire built around him would not burn him, and that when he was stabbed to death, so much blood issued from his body that it quenched the flames around him. Polycarp is recognized as a saint in both the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. 4. Both Irenaeus, who as a young man heard Polycarp speak, and Tertullian recorded that Polycarp had been a disciple of John the Apostle. 5. There are two chief sources of information concerning the life of Polycarp: the letter of the Smyrnaeans recounting the martyrdom of Polycarp and the passages in Irenaeus' Adversus Haereses. Other sources are the epistles of Ignatius, which include one to Polycarp and another to the Smyrnaeans, and Polycarp's own letter to the Philippians. In 1999, some third to 6th-century Coptic fragments about Polycarp were also published. -

The Trinitarian Theology of Irenaeus of Lyons

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects The Trinitarian Theology of Irenaeus of Lyons Jackson Jay Lashier Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Lashier, Jackson Jay, "The Trinitarian Theology of Irenaeus of Lyons" (2011). Dissertations (1934 -). 109. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/109 THE TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY OF IRENAEUS OF LYONS by Jackson Lashier, B.A., M.Div. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2011 ABSTRACT THE TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY OF IRENAEUS OF LYONS Jackson Lashier, B.A., M.Div. Marquette University, 2011 This dissertation is a study of the Trinitarian theology of Irenaeus of Lyons. With the exception of two recent studies, Irenaeus’ Trinitarian theology, particularly in its immanent manifestation, has been devalued by scholarship due to his early dates and his stated purpose of avoiding speculative theology. In contrast to this majority opinion, I argue that Irenaeus’ works show a mature understanding of the Trinity, in both its immanent and economic manifestations, which is occasioned by Valentinianism. Moreover, his Trinitarian theology represents a significant advancement upon that of his sources, the so-called apologists, whose understanding of the divine nature converges in many respects with Valentinian theology. I display this advancement by comparing the thought of Irenaeus with that of Justin, Athenagoras, and Theophilus, on Trinitarian themes. Irenaeus develops Trinitarian theology in the following ways. First, he defines God’s nature as spirit, thus maintaining the divine transcendence through God’s higher order of being as opposed to the use of spatial imagery (God is separated/far away from creation). -

Bede As a Classical and a Patristic Scholar,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 16 (1933): 69-93

M.L.W. Laistner, “Bede as a Classical and a Patristic Scholar,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 16 (1933): 69-93. Bede as a Classical and a Patristic Scholar1 M.L.W. Laistner, M.A., F.R.Hist.S. [p.69] Read 11 May, 1933. Along the many and complex problems with which the history of Europe in the Middle Ages―and especially the earlier period of the Middle Ages―teems is the character of the intellectual heritage transmitted to medieval men from classical and later Roman imperial times. The topic has engaged the attention of many scholars, amongst them men of the greatest eminence, so that much which fifty years ago was still dark and uncertain is now clear and beyond dispute. Yet the old notions and misconceptions die hard, especially in books approximating to the text book class. In a recently published volume on the Middle Ages intended for university freshmen there is much that is excellent and abreast of the most recent investigations; but the sections on early medieval education and scholarship seem to show that the author has never read anything on that subject later than Mullinger’s Schools of Charles the Great. Even in larger works it is not uncommon to find the author merely repeating what the last man before him has said, without inquiring into controversial matters for himself. Years ago Ludwig Traube pointed the way to a correct estimate of Greek studies [p.70] in Western Europe during the earlier Middle Ages, and subsequent research, while it has greatly added to the evidence collected by him, has only fortified his general conclusions. -

The Tetragrammaton Among the Orthodox in Late Antiquity1

chapter 3 The Tetragrammaton among the Orthodox in Late Antiquity1 In this chapter we shall consider first explicit mention of the Tetragrammaton among the Church Fathers. This material was to form the basis of the intellectual heritage on the divine name which they transmitted to the Middle Ages and the early modern period, and it is for ease of later reference that I isolate that mate- rial rather artificially here. Thereafter we shall explore more fully their thoughts on the name of God when we consider their interpretations of Exodus 3:14. We have anticipated repeatedly the emergence of a Christian Greek Old Testament—and, indeed, the New—without the Tetragrammaton and with the general substitution of kurios for it. By the end of the 1st century a.d. it would appear this version had been taken up by the Christians and was at the same time being progressively avoided by Jews.2 The substitution of kurios in the Septuagint, and thence of dominus in the Vulgate, effectively removed the name of God from the awareness of those who read or heard read these Scriptures. As we have seen, Exodus 3:14 thereby effectively ceased to be an explanation of the Tetragrammaton, but rather became an independent state- ment of God’s existence. The Tetragrammaton was simply not in their Bibles, nor did its absence draw attention to itself. Explicit Mention of the Tetragrammaton among the Fathers3 Such learned comment as is found among the early Fathers of the Church on the subject of the Tetragrammaton may now receive our attention. -

Pope Cornelius

Pope Cornelius Pope Cornelius (died June 253) was the Bishop of Rome from 6 or 13 March 251 to his martyrdom in 253.[1] 1 Christian persecution Emperor Decius, who ruled from 249 to 251 AD, per- secuted Christians in the Roman Empire rather sporadi- cally and locally, but starting January in the year 250, he ordered all citizens to perform a religious sacrifice in the presence of commissioners, or else face death.[2] Many Christians refused and were martyred (possibly including the pope, St Fabian, on 20 January), while others partook in the sacrifices in order to save their own lives.[3] Two schools of thought arose after the persecution. One side, led by Novatian, who was a priest in the diocese of Rome, believed that those who had stopped practising Christian- ity during the persecution could not be accepted back into the church even if they repented. Under this philosophy, the only way to re-enter the church would be re-baptism. The opposing side, including Cornelius and Cyprian the Bishop of Carthage, did not believe in the need for re- baptism. Instead they thought that the sinners should only need to show contrition and true repentance to be wel- comed back into the church.[4] In hopes that Christian- ity would fade away, Decius prevented the election of a new pope. However, soon afterwards Decius was forced to leave the area to fight the invading Goths and while he was away the elections for pope were held.[3] In the 14 months without a pope, the leading candidate, Moses, had died under the persecution.