North American Burkitt's Lymphoma Presenting with Intraoral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alveolar Ridge Preservation at Different Anatomical Locations

ALVEOLAR RIDGE PRESERVATION AT DIFFERENT ANATOMICAL LOCATIONS- CLINICAL AND HISTOLOGICAL EVALUATION OF TREATMENT OUTCOME MASTERS THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Dentistry in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mabel Salas, DDS Graduate Program in Dentistry The Ohio State University 2009 Master’s Examination Committee: Binnaz Leblebicioglu, DDS, MS, PhD, Advisor Dimitris N. Tatakis, DDS, PhD Suda Agarwal, PhD Do-Gyoon Kim, PhD Copyright by Mabel Salas 2009 ABSTRACT Background: Alveolar ridge preservation (ARP) is a surgical technique designed to prevent naturally occurring post-extraction bone resorption. It is well documented that alveolar bone height and width are reduced following tooth extraction as a result of physiologic bone remodeling. Depending on the type of post-extraction intrabony defect, an immediate or early implant placement itself may preserve the bone height and width. However, if the defect is generally too wide for immediate and/or early implant placement, it is recommended to perform ARP surgery to preserve the bone volume for future implant placement. The purpose of this study was to investigate clinical and histological healing outcomes following ARP performed on molar and premolar sites by using freeze-dried bone allograft (FDBA) together with a collagen membrane. Maxillary and mandibular sextants were compared for clinical and histological parameters. Methods: Patients who were scheduled to have tooth extraction and implant placement for a molar or premolar tooth were included into this study. Inclusion criteria were single tooth extraction with intact mesial and distal adjacent teeth. Exclusion criteria were smokers, systemic health problems that may affect wound healing and acute infection ii that may prevent bone graft placement. -

Quantitative Analysis of Bcl-2 Expression in Normal and Leukemic Human B-Cell Differentiation

Leukemia (2004) 18, 491–498 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0887-6924/04 $25.00 www.nature.com/leu Quantitative analysis of bcl-2 expression in normal and leukemic human B-cell differentiation P Menendez1,2, A Vargas3, C Bueno1,2, S Barrena1,2, J Almeida1,2 M de Santiago1,2,ALo´pez1,2, S Roa2, JF San Miguel2,4 and A Orfao1,2 1Servicio General de Citometrı´a, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain; 2Departamento de Medicina and Centro de Investigacio´n del Ca´ncer, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain; 3Servicio de Inmunodiagno´stico, Departamento de Patologı´a Clı´nica, Hospital Nacional Edgardo Rebagliati Martins, Lima, Peru´, ; and 4Servicio de Hematologı´a, Hospital Universitario, Salamanca, Spain Lack of apoptosis has been linked to prolonged survival of results in the overexpression of the bcl-2 protein and it malignant B cells expressing bcl-2. The aim of the present represented the first clear example of a common step in study was to analyze the amount of bcl-2 protein expressed 9,10 along normal human B-cell maturation and to establish the oncogenesis mediated by decreased cell death. Currently, frequency of aberrant bcl-2 expression in B-cell malignancies. the exact antiapoptotic pathways through which bcl-2 exerts its In normal bone marrow (n ¼ 11), bcl-2 expression obtained by role are only partially understood, involving decreased mito- quantitative multiparametric flow cytometry was highly vari- chondrial release of cytochrome c, which in turn is required for þ À able: very low in both CD34 and CD34 B-cell precursors, high the activation of procaspase-9 and the subsequent initiation of in mature B-lymphocytes and very high in plasma cells. -

Lecture 2 – Bone

Oral Histology Summary Notes Enoch Ng Lecture 2 – Bone - Protection of brain, lungs, other internal organs - Structural support for heart, lungs, and marrow - Attachment sites for muscles - Mineral reservoir for calcium (99% of body’s) and phosphorous (85% of body’s) - Trap for dangerous minerals (ex:// lead) - Transduction of sound - Endocrine organ (osteocalcin regulates insulin signaling, glucose metabolism, and fat mass) Structure - Compact/Cortical o Diaphysis of long bone, “envelope” of cuboid bones (vertebrae) o 10% porosity, 70-80% calcified (4x mass of trabecular bone) o Protective, subject to bending/torsion/compressive forces o Has Haversian system structure - Trabecular/Cancellous o Metaphysis and epiphysis of long bone, cuboid bone o 3D branching lattice formed along areas of mechanical stress o 50-90% porosity, 15-25% calcified (1/4 mass of compact bone) o High surface area high cellular activity (has marrow) o Metabolic turnover 8x greater than cortical bone o Subject to compressive forces o Trabeculae lined with endosteum (contains osteoprogenitors, osteoblasts, osteoclasts) - Woven Bone o Immature/primitive, rapidly growing . Normally – embryos, newborns, fracture calluses, metaphyseal region of bone . Abnormally – tumors, osteogenesis imperfecta, Pagetic bone o Disorganized, no uniform orientation of collagen fibers, coarse fibers, cells randomly arranged, varying mineral content, isotropic mechanical behavior (behavior the same no matter direction of applied force) - Lamellar Bone o Mature bone, remodeling of woven -

Periodontal Ligament, Cementum, and Alveolar Bone in the Oldest Herbivorous Tetrapods, and Their Evolutionary Significance

Periodontal Ligament, Cementum, and Alveolar Bone in the Oldest Herbivorous Tetrapods, and Their Evolutionary Significance Aaron R. H. LeBlanc*, Robert R. Reisz Department of Biology, University of Toronto Mississauga, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada Abstract Tooth implantation provides important phylogenetic and functional information about the dentitions of amniotes. Traditionally, only mammals and crocodilians have been considered truly thecodont, because their tooth roots are coated in layers of cementum for anchorage of the periodontal ligament, which is in turn attached to the bone lining the alveolus, the alveolar bone. The histological properties and developmental origins of these three periodontal tissues have been studied extensively in mammals and crocodilians, but the identities of the periodontal tissues in other amniotes remain poorly studied. Early work on dental histology of basal amniotes concluded that most possess a simplified tooth attachment in which the tooth root is ankylosed to a pedestal composed of ‘‘bone of attachment’’, which is in turn fused to the jaw. More recent studies have concluded that stereotypically thecodont tissues are also present in non-mammalian, non-crocodilian amniotes, but these studies were limited to crown groups or secondarily aquatic reptiles. As the sister group to Amniota, and the first tetrapods to exhibit dental occlusion, diadectids are the ideal candidates for studies of dental evolution among terrestrial vertebrates because they can be used to test hypotheses of development and homology in deep time. Our study of Permo-Carboniferous diadectid tetrapod teeth and dental tissues reveal the presence of two types of cementum, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone, and therefore the earliest record of true thecodonty in a tetrapod. -

The Preservation of Alveolar Bone Ridge During Tooth Extraction Marius Kubilius, Ricardas Kubilius, Alvydas Gleiznys

REVIEWS SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES Stomatologija, Baltic Dental and Maxillofacial Journal, 14: 3-11, 2012 The preservation of alveolar bone ridge during tooth extraction Marius Kubilius, Ricardas Kubilius, Alvydas Gleiznys SUMMARY Objectives. The aims were to overview healing of extraction socket, recommendations for atraumatic tooth extraction, possibilities of post extraction socket bone and soft tissues preservation, augmentation. Materials and Methods. A search was done in Pubmed on key words in English from 1962 to December 2011. Additionally, last decades different scientifi c publications, books from ref- erence list were assessed for appropriate review if relevant. Results and conclusions. There was made intraalveolar and extraalveolar postextractional socket healing overview. There was established the importance and effectiveness of atraumatic tooth extraction and subsequent postextractional socket augmentation in limited hard and soft tissue defects. There are many different methods, techniques, periods, materials in regard to the review. It is diffi cult to compare the data and to give the priority to one. Key words: tooth extraction, grafting, socket, healing, ridge preservation. INTRODUCTION Nowadays tooth extraction becomes more im- portunity to get acknowledge with summarized con- portant in complex odontological treatment. Three temporary scientifi c publication results, methodologies dimensional bones’ and soft tissue parameters infl u- and practical recommendations in preserving alveolar ence further treatment plan, results and long time crest in tooth extraction (validity for atraumatic tooth prognosis. Tooth extraction inevitably has infl uence extraction, operative methods, protection of alveolus in bone resorption and changes in gingival contours. after extractions, feasible post extraction fi llers and Further treatment may become more complex in using complications, alternative treatment). -

SNF Mobility Model: ICD-10 HCC Crosswalk, V. 3.0.1

The mapping below corresponds to NQF #2634 and NQF #2636. HCC # ICD-10 Code ICD-10 Code Category This is a filter ceThis is a filter cellThis is a filter cell 3 A0101 Typhoid meningitis 3 A0221 Salmonella meningitis 3 A066 Amebic brain abscess 3 A170 Tuberculous meningitis 3 A171 Meningeal tuberculoma 3 A1781 Tuberculoma of brain and spinal cord 3 A1782 Tuberculous meningoencephalitis 3 A1783 Tuberculous neuritis 3 A1789 Other tuberculosis of nervous system 3 A179 Tuberculosis of nervous system, unspecified 3 A203 Plague meningitis 3 A2781 Aseptic meningitis in leptospirosis 3 A3211 Listerial meningitis 3 A3212 Listerial meningoencephalitis 3 A34 Obstetrical tetanus 3 A35 Other tetanus 3 A390 Meningococcal meningitis 3 A3981 Meningococcal encephalitis 3 A4281 Actinomycotic meningitis 3 A4282 Actinomycotic encephalitis 3 A5040 Late congenital neurosyphilis, unspecified 3 A5041 Late congenital syphilitic meningitis 3 A5042 Late congenital syphilitic encephalitis 3 A5043 Late congenital syphilitic polyneuropathy 3 A5044 Late congenital syphilitic optic nerve atrophy 3 A5045 Juvenile general paresis 3 A5049 Other late congenital neurosyphilis 3 A5141 Secondary syphilitic meningitis 3 A5210 Symptomatic neurosyphilis, unspecified 3 A5211 Tabes dorsalis 3 A5212 Other cerebrospinal syphilis 3 A5213 Late syphilitic meningitis 3 A5214 Late syphilitic encephalitis 3 A5215 Late syphilitic neuropathy 3 A5216 Charcot's arthropathy (tabetic) 3 A5217 General paresis 3 A5219 Other symptomatic neurosyphilis 3 A522 Asymptomatic neurosyphilis 3 A523 Neurosyphilis, -

Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Lymphoproliferative disorders Objectives: • To understand the general features of lymphoproliferative disorders (LPD) • To understand some benign causes of LPD such as infectious mononucleosis • To understand the general classification of malignant LPD Important. • To understand the clinicopathological features of chronic lymphoid leukemia Extra. • To understand the general features of the most common Notes (LPD) (Burkitt lymphoma, Follicular • lymphoma, multiple myeloma and Hodgkin lymphoma). Success is the result of perfection, hard work, learning Powellfrom failure, loyalty, and persistence. Colin References: Editing file 435 teamwork slides 6 girls & boys slides Do you have any suggestions? Please contact us! @haematology436 E-mail: [email protected] or simply use this form Definitions Lymphoma (20min) Lymphoproliferative disorders: Several clinical conditions in which lymphocytes are produced in excessive quantities (Lymphocytosis) increase in lymphocytes that are not normal Lymphoma: Malignant lymphoid mass involving the lymphoid tissues. (± other tissues e.g: skin, GIT, CNS ..) The main deference between Lymphoma & Leukemia is that the Lymphoma proliferate primarily in Lymphoid Tissue and cause Mass , While Leukemia proliferate mainly in BM& Peripheral blood Lymphoid leukemia: Malignant proliferation of lymphoid cells in Bone marrow and peripheral blood. (± other tissues e.g: lymph nodes, spleen, skin, GIT, CNS ..) BCL is an anti-apoptotic (prevent apoptosis) Lymphocytosis (causes) 1- Viral infection: 2- Some* bacterial -

Non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin Lymphomas Select for Overexpression of BCLW Clare M

Published OnlineFirst August 29, 2017; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1144 Biology of Human Tumors Clinical Cancer Research Non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin Lymphomas Select for Overexpression of BCLW Clare M. Adams1, Ramkrishna Mitra1, Jerald Z. Gong2, and Christine M. Eischen1 Abstract Purpose: B-cell lymphomas must acquire resistance to apopto- follicular, mantle cell, marginal zone, and Hodgkin lymphomas. sis during their development. We recently discovered BCLW, an Notably, BCLW was preferentially overexpressed over that of antiapoptotic BCL2 family member thought only to contribute to BCL2 and negatively correlated with BCL2 in specific lymphomas. spermatogenesis, was overexpressed in diffuse large B-cell lym- Unexpectedly, BCLW was overexpressed as frequently as BCL2 in phoma (DLBCL) and Burkitt lymphoma. To gain insight into the follicular lymphoma. Evaluation of all five antiapoptotic BCL2 contribution of BCLW to B-cell lymphomas and its potential to family members in six types of B-cell lymphoma revealed that confer resistance to BCL2 inhibitors, we investigated the expres- BCL2, BCLW, and BCLX were consistently overexpressed, whereas sion of BCLW and the other antiapoptotic BCL2 family members MCL1 and A1 were not. In addition, individual lymphomas in six different B-cell lymphomas. frequently overexpressed more than one antiapoptotic BCL2 Experimental Design: We performed a large-scale gene family member. expression analysis of datasets comprising approximately Conclusions: Our comprehensive analysis indicates B-cell 2,300 lymphoma patient samples, including non-Hodgkin lymphomas commonly select for BCLW overexpression in andHodgkinlymphomasaswellasindolentandaggressive combination with or instead of other antiapoptotic BCL2 lymphomas. Data were validated experimentally with qRT- family members. Our results suggest BCLW may be equally as PCR and IHC. -

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Rick, non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivor This publication was supported in part by grants from Revised 2013 A Message From John Walter President and CEO of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) believes we are living at an extraordinary moment. LLS is committed to bringing you the most up-to-date blood cancer information. We know how important it is for you to have an accurate understanding of your diagnosis, treatment and support options. An important part of our mission is bringing you the latest information about advances in treatment for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, so you can work with your healthcare team to determine the best options for the best outcomes. Our vision is that one day the great majority of people who have been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma will be cured or will be able to manage their disease with a good quality of life. We hope that the information in this publication will help you along your journey. LLS is the world’s largest voluntary health organization dedicated to funding blood cancer research, education and patient services. Since 1954, LLS has been a driving force behind almost every treatment breakthrough for patients with blood cancers, and we have awarded almost $1 billion to fund blood cancer research. Our commitment to pioneering science has contributed to an unprecedented rise in survival rates for people with many different blood cancers. Until there is a cure, LLS will continue to invest in research, patient support programs and services that improve the quality of life for patients and families. -

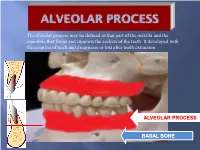

Alveolar Process May Be Defined As That Part of the Maxilla and the Mandible That Forms and Supports the Sockets of the Teeth

The alveolar process may be defined as that part of the maxilla and the mandible that forms and supports the sockets of the teeth. It developed with the eruption of teeth and disappears or lost after tooth extraction ALVEOLAR PROCESS BASAL BONE Alveolar (bone) process: is that part of the maxilla and the mandible that forms and supports the sockets of the teeth. Basal Bone. it is the bone of the facial skeleton which support the alveolar bone. There is no anatomical boundary between basal bones and alveolar bone. Both alveolar process and basal bone are covered by the same periosteum. In some areas alveolar processes may fuse or masked with jaw bones as in (1) Anterior part of maxilla (palatal). (2) Oblique line of the mandible. * Alveolar process is resorbed after extraction of teeth. Functions of alveolar bone – Houses and protects developing permanent teeth, while supporting primary teeth. – Organizes eruption of primary and permanent teeth. – Anchors the roots of teeth to the alveoli, which is achieved by the insertion of Sharpey’s fibers into the alveolar bone proper (attachment). – Helps to move the teeth for better occlusion (support). – Helps to absorb and distribute occlusal forces generated during tooth contact (shock absorber). – Supplies vessels to periodontal ligament. •DEVELOPMENT OF ALVEOLAR BONE •Near the end of the second month of fetal life, the maxilla as well as the mandible form a groove that is open towards the surface of the oral cavity. •Tooth germs develop within the bony structures at late bell stage. •Bony septa and bony bridge begin to form and separatethe individual tooth germs from one another, keeping individual tooth germs in clearly outlined bony compartments. -

Mature B-Cell Neoplasms

PEARLS OF LABORATORY MEDICINE Mature B-cell Neoplasms Michael Moravek, MD Kamran M. Mirza, MD, PhD Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine DOI: 10.15428/CCTC.2018.287706 © Clinical Chemistry The Lymphoid System Bone Marrow Stem Cell • Mature B-cell lymphomas comprise approximately 75% of all lymphoid neoplasms • Genetic alterations lead to deregulation of cell T cell Immature NK cell proliferation or apoptosis B cell • Low-grade lymphomas typically present as painless B cell lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or incidental lymphocytosis • High-grade lymphomas typically present with a rapidly enlarging mass and “B” symptoms (fever, weight loss, night sweats) Plasma cell 2 B-Cell Maturation antigen Naïve B cell Post- Germinal Center Germinal Center Marginal Zone DLBCL (some) FL, BL, some DLBCL, CLL/SLL Mantle Cell Hodgkin lymphoma MZL MALT Lymphoma Plasma cell myeloma CD5 + CD10 + CD5/CD10 Neg 3 Frequency among mature B-cell neoplasms DLBCL 27.6% CLL/SLL 19.4% Mature B-cell neoplasms Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma Follicular Lymphoma -Monoclonal B-12.2%cell lymphocytosis Mantle cell lymphoma Marginal Zone LymphomaB-cell prolymphocytic 3.7% leukemia -Leukemic non-nodal mantle cell lymphoma Splenic marginal zone lymphoma -In situ mantle cell neoplasia Mantle Cell LymphomaHairy cell leukemia1.9% Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), NOS Splenic B-cell lymphoma/leukemia, unclassifiable -Germinal center B-cell type Burkitt Lymphoma -Splenic diffuse1.3% red pulp -

Burkitt Lymphoma

Board Review- Part 2B: Malignant HemePath 4/25/2018 Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma SLL: epidemiology SLL: 6.7% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Majority of patients >50 y/o (median 65). M:F ratio 2:1. Morphology • Lymph nodes – Effacement of architecture, pseudofollicular pattern of pale areas of large cells in a dark background of small cells. Occasionally is interfollicular. – The predominant cell is a small lymphocyte with clumped chromatin, round nucleus, ocassionally a nucleolus. – Mitotic activity usually very low. Morphology - Pseudofollicles or proliferation centers contain small, medium and large cells. - Prolymphocytes are medium-sized with dispersed chromatin and small nucleoli. - Paraimmunoblasts are medium to large cells with round to oval nuclei, dispersed chromatin, central eosinophilic nucleoli and slightly basophilic cytoplasm. Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma Pseudo-follicle Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma Prolymphocyte Paraimmunoblast Immunophenotype Express weak or dim surface IgM or IgM and IgD, CD5, CD19, CD20 (weak), CD22 (weak), CD79a, CD23, CD43, CD11c (weak). CD10-, cyclin D1-. FMC7 and CD79b negative or weak. Immunophenotype Cases with unmutated Ig variable region genes are reported to be CD38+ and ZAP70+. Immunophenotype Cytoplasmic Ig is detectable in about 5% of the cases. CD5 and CD23 are useful in distinguishing from MCL. Rarely CLL is CD23-. Rarely MCL is CD23+. Perform Cyclin D1 in CD5+/CD23- cases. Some cases with typical CLL morphology may have a different profile (CD5- or CD23-, FMC7+ or CD11c+, or strong sIg, or CD79b+). Genetics Antigen receptor genes: Ig heavy and light chain genes are rearranged. Suggestion of 2 distinct types of SLL defined by the mutational status of the IgVH genes: 40-50% show no somatic mutations of their variable region genes (naïve cells, unmutated).