TOURISMOS Is an International, Multi-Disciplinary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Environmental Management Report

Annual Environmental Management Report Reporting Period: 1/1/2018÷ 31/12/2018 Submitted to EYPE/Ministry of the Environment, Planning and Public Works within the framework of the JMDs regarding the Approval of the Environmental Terms of the Project & to the Greek State in accordance with Article 17.5 of the Concession Agreement Aegean Motorway S.A. – Annual Environmental Management Report – January 2019 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 2. The Company ............................................................................................................... 3 3. Scope .......................................................................................................................... 4 4. Facilities ....................................................................................................................... 8 5. Organization of the Concessionaire .............................................................................. 10 6. Integrated Management System .................................................................................. 11 7. Environmental matters 2018 ....................................................................................... 13 8. 2018 Public Relations & Corporate Social Responsibility Activity ..................................... 32 Appendix 1 ........................................................................................................................ 35 MANAGEMENT -

Tourism Development in Greek Insular and Coastal Areas: Sociocultural Changes and Crucial Policy Issues

Tourism Development in Greek Insular and Coastal Areas: Sociocultural Changes and Crucial Policy Issues Paris Tsartas University of the Aegean, Michalon 8, 82100 Chios, Greece The paperanalyses two issuesthat have characterised tourism development inGreek insularand coastalareas in theperiod 1970–2000. The firstissue concerns the socioeco- nomic and culturalchanges that have taken place in theseareas and ledto rapid– and usuallyunplanned –tourismdevelopment. The secondissue consists of thepolicies for tourismand tourismdevelopment atlocal,regional and nationallevel. The analysis focuseson therole of thefamily, social mobility issues,the social role of specific groups, and consequencesfor the manners, customs and traditionsof thelocal popula- tion.It also examines the views and reactionsof localcommunities regarding tourism and tourists.There is consideration of thenew productive structuresin theseareas, including thedowngrading of agriculture,the dependence of many economicsectors on tourism,and thelarge increase in multi-activityand theblack economy. Another focusis on thecharacteristics of masstourism, and on therelated problems and criti- cismsof currenttourism policies. These issues contributed to amodel of tourism development thatintegrates the productive, environmental and culturalcharacteristics of eachregion. Finally, the procedures and problemsencountered in sustainabledevel- opment programmes aiming at protecting the environment are considered. Social and Cultural Changes Brought About by Tourism Development in the Period 1970–2000 The analysishere focuseson three mainareas where these changesare observed:sociocultural life, productionand communication. It should be noted thata large proportionof all empirical studies of changesbrought aboutby tourism development in Greece have been of coastal and insular areas. Social and cultural changes in the social structure The mostsignificant of these changesconcern the family andits role in the new ‘urbanised’social structure, social mobility and the choicesof important groups, such as young people and women. -

The Primal Greece : Between Dream and Archaeology

The primal Greece : between dream and archaeology Introduction The Aegean civilisations in the French National Archaeological Museum « This unusual form […] reveals an unknown Greece within Greece […] as solemn, profound and colossal as the other is radiant, light and considered; […] all here meets the reputation of the Atrids and brings back the horror of the Achaean fables », wrote on 1830 in front of the walls of Mycenae, the traveller Edgard Quinet, who was passionate about Greek tragedies. Like other travellers before him, he was aware of approaching the memory of an unknown past, of a primal Greece, but he would never have believed that this Greece dated from prehistoric times. It will be the end of the 19th century before the pioneers of archaeology reveal to the world the first civilisations of the Aegean. The « Museum of National Antiquities» played then a key role, spreading the knowledge about these fabulous finds. Here, as well as in the Louvre, the public has been able to meet the Aegean civilisations. The Comparative Archaeology department had a big display case entirely dedicated to them. The exhibition invites visitors back to this era of endless possibilities in order to experience this great archaeological adventure. Birth of a state, birth of an archaeology As soon as it becomes independent (1832), Greece is concerned with preserving its antiquities and creates an Archaeological Service (1834). Shortly afterwards, Ephemeris Archaiologike, the first Greek archaeological review, is founded, at the same time as the Archaeological Society at Athens. The French School at Athens is founded in 1846 in order to promote the study of antiquities, and is followed by a German study Institute in 1874; many other countries will follow the example of France and Germany. -

Greek Tourism and Economic Crisis in Historical Perspective: the Case of Travel Agencies, Interwar Years

Greek tourism and economic crisis in historical perspective: The case of travel agencies, interwar years Abstract The interwar years may be considered as a key period for Greek tourism. Prepaid packages, group carriage, larger hotel and travel firms and finally, state policies signified the transition to modern tourist practices and opened the way to the mass tourism phase after the Second World War. The period under examination has had an ambiguous benchmark, however, in terms of the degree of negative impacts. Undoubtedly the aftermath of the world economic crisis and the following bankruptcy of the Greek state affected all economic activities. Statistics as well as personal business archives reveal the extent of the consequences on Greek tourism and its transition-growth procedure. In the current paper, travel business is examined. More specifically, the types of organisations, motives of entrepreneurship, strategy and management patterns at the time of crisis, are related to the ability of surpassing the problems and to their continuity. The paper suggests that the economic implications were a challenge for Greek tourism and travel business that overcame the problems, in the long term. The private sector tried to exploit the favouring circumstances and the dynamism that followed but this was not the case for the public sector. Introduction Mediterranean economies increasingly rely on tourism revenue; for Greece tourism is considered the main economic activity. Lately, while a deep depression has set in the country, political and economic analysts’ discussion, has focused on tourism and its possibilities to help the economy confront the negative effects of the crisis. A retrospective glance on previous crises may generate interesting observations about policies and strategies to overcome depressions. -

Tourism in Greece!

Tourism in Greece! Semiramis Ampatzoglou Konstantina Vlachou Greece is more preferable for tourists during the summer season because this period of time allows you to enjoy the finest things in our country. Most tourists visit Greece to discover our great history and culture as well as to have fun and relax in our beautiful islands! Greece has a great variety of things you can do and, the most important is that, it even satisfies the most demanding tourists…! Now, let’s show you some places you should definitely visit! Museums The Acropolis Museum: The Acropolis Museum is an archaeological museum focused on the findings of the archaeological site of the Acropolis of Athens. The Archeological Museum of Delphi: The Archaeological Museum of Delphi, one of the most important in Greece, exhibits the history of the Delphic sanctuary, site of the most famous ancient Greek oracle. The National Gallery: The gallery exhibitions are mainly focused on post-Byzantine Greek Art. The gallery owns and exhibits also an extensive collection of European artists. Particularly valuable is the collection of paintings from the Renaissance. Museums The Acropolis Museum The National Gallery of Athens The Archeological Museum of Delphi Monuments The Parthenon: The Parthenon is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. The Panathenaic Stadium: The Panathenaic Stadium is located on the site of an ancient stadium and for many centuries hosted games in which naked male athletes competed in track events, athletic championships as we would call them today. The Temple of Olympian Zeus: The Temple of Olympian Zeus is a colossal ruined temple in the centre of the Greek capital Athens that was dedicated to Zeus, king of the Olympian gods. -

Development of a Cycle-Tourism Strategy in Greece Based on the Preferences of Potential Cycle-Tourists

sustainability Article Development of a Cycle-Tourism Strategy in Greece Based on the Preferences of Potential Cycle-Tourists Efthimios Bakogiannis 1, Thanos Vlastos 1, Konstantinos Athanasopoulos 1, Georgia Christodoulopoulou 1, Christos Karolemeas 1 , Charalampos Kyriakidis 1,*, Maria-Stella Noutsou 2, Trisevgeni Papagerasimou-Klironomou 1, Maria Siti 1, Ismini Stroumpou 2, Avgi Vassi 1, Stefanos Tsigdinos 1 and Eleftheria Tzika 1 1 Department of Geography and Regional Planning, School of Rural and Surveying Engineering, National Technical University of Athens (NTUA), 9, H. Polytechniou Str., Zographou Campus, 15780 Athens, Greece; [email protected] (E.B.); [email protected] (T.V.); [email protected] (K.A.); [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (C.K.); [email protected] (T.P.-K.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (A.V.); [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (E.T.) 2 AETHON Engineering Consultants P.C., 10678,Athens, Greece; [email protected] (M.-S.N.); [email protected] (I.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +30-210-772-11-53 Received: 25 February 2020; Accepted: 17 March 2020; Published: 19 March 2020 Abstract: Cycle-tourism seems to be an emerging touristic model in many countries, including Greece. Although the infrastructure is limited, entrepreneurship can support the development of such tourism sector, as cycle-tourists have specific needs to be met during an excursion. Thus, it would be helpful if stores that meet specific prerequisites could be certificated as cycle-friendly companies. In order for such certification to be developed, it is necessary for those parameters to be defined. -

Tourism and Income in Greece: a Market Solution to the Debt Crisis1

Athens Journal of Tourism - Volume 4, Issue 2 – Pages 97-110 Tourism and Income in Greece: A Market Solution to the Debt Crisis1 By Henry Thompson The tourism industry is showing increased income due to specialization and trade offers Greece the solution to its sovereign debt crisis. Opening the economy to investment and competition, not only in tourism but across all sectors, would raise income and relieve the burden of paying the government debt. This paper assesses the potential of tourism to lead the transformation of Greece into a competitive economy.1 Tourism has steadily grown in Greece over recent decades due to rising incomes worldwide, declining travel cost, and steady investment by the industry. Tourism is showing that moving toward a competitive market economy could raise income and relieve the taxpayer burden of government debt. The present paper evaluates the expanding tourism industry and its potential to influence the rest of the economy. Tourism is an expanding global industry critical to economic growth in a number of countries. The literature on tourism and growth documents this potential especially among developing countries. The situation of Greece is different in that it is a developed country in the European Union. Greece faces a number of well known structural challenges based on the inefficient legal system, archaic labor laws, restricted international investment, burdensome income and sales tax rates, a weak property tax system, and corrupt government. While the tourism industry has the potential to continue raising income, more critically it illustrates the gains from open market competition, specialization, and trade. The first section presents a brief history of the debt crisis in Greece followed by sections on the tourism sector, its relation to the economy, and macroeconomic issues related to tourism. -

Asset Technology Employment-Entrepreneurship

A sset T echn o lo gy Em plo ym en t-E ntrepreneurship Projects ASSET TECHNOLOGY PROMOTION OF EMPLOYMENT AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT OF THE SOCIAL ECONOMY SECTOR “Local Action Plan for the Integration of Vulnerable Groups - Disabled people, of the Municipalities of Ilion and Agii Anargiri-Kamatero” Development Partnership: ERGAXIA Area of Intervention: Municipalities of Ilion and Agii Anargiri - Kamatero Target Group: People with disabilities http://www.ergaxia.gr “Local Action Plan for the Social Integration of Vulnerable Groups of the Municipality of Pylos-Nestor” Development Partnership: PALAIPYLOS Area of Intervention: Municipality of Pylos-Nestor Target Group: Long term unemployed over the age of 45, unemployed living in poverty http://www.palaipylos.gr/ “Local Action Plan for the Social Integration of Vulnerable Groups of the Municipalities of Argithea, Mouzaki, Palamas, Sofades” Development Partnership: KIERION Area of Intervention: Municipalities of Argithea, Mouzaki, Palamas, Sofades / Karditsa Regional Unit Target Group: Long term unemployed over the age of 45, unemployed living in poverty http://www.topeko-kierion.gr/ “Local Action Plan for the Social Integration of Vulnerable Groups of Thesprotia” Development Partnership: THESPROTIAN SOCIAL COOPERATION Area of Intervention: Regional Unit of Thesprotia Target Group: Long term unemployed over the age of 45, unemployed living in poverty http://www.thekoisi.gr/ “Local Action Plan for Employment «HERMES»” Development Partnership: TOPSA HERMES Area of Intervention: Regional Unit of Thessaloniki Target Group: Unemployed women and young people, young scientists http://www.topsa-hermes.gr/ “Local Action Plan for the Development of Employment in Amfiloxia” Development Partnership: D.P. Amfiloxia Area of Intervention: Municipality of Amfiloxia Target Group: Unemployed women and young people, young scientists and farmers http://www.topsa-amfiloxia.gr/ “Local Action Plan for the Development of Employment in Sikionion Municipality” Development Partnership: D.P. -

Travel Business History in Greece: Entrepreneurial and Financial Practices

Travel business history in Greece: entrepreneurial and financial practices Abstract The current draft paper is a part of an ongoing research in the context of my dissertation regarding the history of tourism and especially the evolution of travel business in Greece since the late 19th century. The information gathered, is mainly primary, and was drawn from the historical Greek press, travel guides, archives of people whose families ran travel enterprises in the past, and archives of public services such as the National Tourism Organization. Tourism-oriented policies were developed in Greece later than in other European countries; important steps were made during the interwar years and after the Second World War. During the pre-First World War era, the private tourism sector was the main driving force of changes in traveling. Travel agencies’ role was of overwhelming importance; Thomas Cook’s agencies changed completely the concept of traveling with the introduction and gradual expansion of pre-paid traveling packages. During the interwar years government intervention started; It then accelerated after the Second World War. Keywords: Tourism, travel agencies, entrepreneurship, finance, public policies Early entrepreneurial and financial practices in the business of travel During the mid-nineteenth century the prevailing circumstances in Greece did not favor a systematic tourism development. The country was preoccupied with efforts to stabilize its political system. In the late 19th century railway transport and road networks were still inadequate1. In the 1880’s Greece under the leadership of Charilaos Trikoupis begun sustained effort for economic development. The improvement of communications and transport was central in these efforts. -

Christians and Jews Hand in Hand Against the Occupiers Resistance

DIDACTIC UNIT 1 Christians and Jews hand in hand against the Occupiers Resistance 28th Lyceum of Thessaloniki, Greece 2014-2017 Christians and Jews hand in hand against the Occupiers Resistance 28th Lyceum of Thessaloniki, Greece Table of contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 2 BIOGRAPHY RATIONALE ........................................................................................................................... 22 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ...................................................................................................................... 23 From the Declaration of war (October 1940) to the liberation of Greece (October 1944) ................. 23 The living conditions during the occupation of Greece ....................................................................... 24 Spontaneous acts of resistance, emergence and activity of numerous resistance groups ................. 26 The engineering unit of ELAS in Olympus and the sabotage acts to the trains and the railway tracks .............................................................................................................................................................. 27 The Jewish community of Thessaloniki and its fate ............................................................................. 28 BIOGRAPHY .............................................................................................................................................. -

Fhu2xellcj7lgbnexipovzl4g6a.Pdf

Griechenland Attika...................................................................................................................................................4 Athen-Zentrum.....................................................................................................................................4 Athen-Nord...........................................................................................................................................5 Athen-Süd.............................................................................................................................................6 Athen-West...........................................................................................................................................7 Piräus....................................................................................................................................................8 Inseln....................................................................................................................................................9 Ostattika..............................................................................................................................................10 Westattika............................................................................................................................................11 Epirus.................................................................................................................................................12 Arta.....................................................................................................................................................12 -

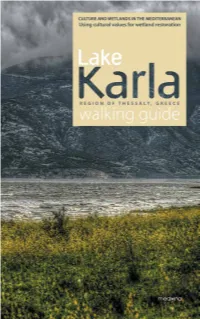

ENG-Karla-Web-Extra-Low.Pdf

231 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration 2 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration Lake Karla walking guide Mediterranean Institute for Nature and Anthropos Med-INA, Athens 2014 3 Edited by Stefanos Dodouras, Irini Lyratzaki and Thymio Papayannis Contributors: Charalampos Alexandrou, Chairman of Kerasia Cultural Association Maria Chamoglou, Ichthyologist, Managing Authority of the Eco-Development Area of Karla-Mavrovouni-Kefalovryso-Velestino Antonia Chasioti, Chairwoman of the Local Council of Kerasia Stefanos Dodouras, Sustainability Consultant PhD, Med-INA Andromachi Economou, Senior Researcher, Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens Vana Georgala, Architect-Planner, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Ifigeneia Kagkalou, Dr of Biology, Polytechnic School, Department of Civil Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace Vasilis Kanakoudis, Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Thessaly Thanos Kastritis, Conservation Manager, Hellenic Ornithological Society Irini Lyratzaki, Anthropologist, Med-INA Maria Magaliou-Pallikari, Forester, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Sofia Margoni, Geomorphologist PhD, School of Engineering, University of Thessaly Antikleia Moudrea-Agrafioti, Archaeologist, Department of History, Archaeology and Social Anthropology, University of Thessaly Triantafyllos Papaioannou, Chairman of the Local Council of Kanalia Aikaterini Polymerou-Kamilaki, Director of the Hellenic Folklore Research