Profile on John Lewis.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REFLECTION REFLECTION the Freedom Riders of the Civil Rights Movement

REFLECTION REFLECTION The Freedom Riders of the Civil Rights Movement “I’m taking a trip on the Greyhound bus line, I’m riding the front seat to New Orleans this time. Hallelujah I’m a travelin’, hallelujah ain’t it fine, Hallelujah I’m a travelin’ down freedom’s main line.” This reflection is based on the PBS documentary, “Freedom Riders,” which is a production of The American Experience. To watch the film, go to: http://to.pbs.org/1VbeNVm. SUMMARY OF THE FILM From May to November 1961, over 400 Americans, both black and white, witnessed the power of nonviolent activism for civil rights. The Freedom Riders were opposing the racist Jim Crow laws of the South by riding bus lines from Washington, D.C., down through the Deep South. These Freedom Rides were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Despite the violence, threats, and extraor- dinary racism they faced, people of conscience, both black and white, Northern and Southern, rich and poor, old and young, carried out the Freedom Rides as a testimony to the basic truth all Americans hold: that the government must protect the constitutional rights of its people. Finally, on September 22, 1961, segregation on the bus lines ended. This was arguably the movement that changed the force and effectiveness of the Civil Rights Movement as a whole and set the stage for other organized movements like the Selma to Montgomery March and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This documentary is based on the book Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Equality by Raymond Arsenault (http://bit.ly/1Vbn4sy). -

How Did the Civil Rights Movement Impact the Lives of African Americans?

Grade 4: Unit 6 How did the Civil Rights Movement impact the lives of African Americans? This instructional task engages students in content related to the following grade-level expectations: • 4.1.41 Produce clear and coherent writing to: o compare and contrast past and present viewpoints on a given historical topic o conduct simple research summarize actions/events and explain significance Content o o differentiate between the 5 regions of the United States • 4.1.7 Summarize primary resources and explain their historical importance • 4.7.1 Identify and summarize significant changes that have been made to the United States Constitution through the amendment process • 4.8.4 Explain how good citizenship can solve a current issue This instructional task asks students to explain the impact of the Civil Rights Movement on African Claims Americans. This instructional task helps students explore and develop claims around the content from unit 6: Unit Connection • How can good citizenship solve a current issue? (4.8.4) Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task 1 Performance Task 2 Performance Task 3 Performance Task 4 How did the 14th What role did Plessy v. What impacts did civic How did Civil Rights Amendment guarantee Ferguson and Brown v. leaders and citizens have legislation affect the Supporting Questions equal rights to U.S. Board of Education on desegregation? lives of African citizens? impact segregation Americans? practices? Students will analyze Students will compare Students will explore how Students will the 14th Amendment to and contrast the citizens’ and civic leaders’ determine the impact determine how the impacts that Plessy v. -

Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, the Montgomery Bus Boycott and The

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. III, 1917-1968 Black Belt Press The ONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT M and the WOMEN WHO STARTED IT __________________________ The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson __________________________ Mrs. Jo Ann Gibson Robinson Black women in Montgomery, Alabama, unlocked a remarkable spirit in their city in late 1955. Sick of segregated public transportation, these women decided to wield their financial power against the city bus system and, led by Jo Ann Gibson Robinson (1912-1992), convinced Montgomery's African Americans to stop using public transportation. Robinson was born in Georgia and attended the segregated schools of Macon. After graduating from Fort Valley State College, she taught school in Macon and eventually went on to earn an M.A. in English at Atlanta University. In 1949 she took a faculty position at Alabama State College in Mont- gomery. There she joined the Women's Political Council. When a Montgomery bus driver insulted her, she vowed to end racial seating on the city's buses. Using her position as president of the Council, she mounted a boycott. She remained active in the civil rights movement in Montgomery until she left that city in 1960. Her story illustrates how the desire on the part of individuals to resist oppression — once *it is organized, led, and aimed at a specific goal — can be transformed into a mass movement. Mrs. T. M. Glass Ch. 2: The Boycott Begins n Friday morning, December 2, 1955, a goodly number of Mont- gomery’s black clergymen happened to be meeting at the Hilliard O Chapel A. -

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF Mourns the Loss of the Honora

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF mourns the loss of The Honorable John Lewis, an esteemed member of Congress and revered civil rights icon with whom our organization has a deeply personal history. Mr. Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. “I don’t know of another leader in this country with the moral standing of Rep. John Lewis. His life and work helped shape the best of our national identity,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s President & Director-Counsel. “We revered him not only for his work and sacrifices during the Civil Rights Movement, but because of his unending, stubborn, brilliant determination to press for justice and equality in this country. “There was no cynicism in John Lewis; no hint of despair even in the darkest moments. Instead, he showed up relentlessly with commitment and determination - but also love, and joy and unwavering dedication to the principles of non-violence. He spoke up and sat-in and stood on the front lines – and risked it all. This country – every single person in this country – owes a debt of gratitude to John Lewis that we can only begin to repay by following his demand that we do more as citizens. That we ‘get in the way.’ That we ‘speak out when we see injustice’ and that we keep our ‘eyes on the prize.’” The son of sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. He grew up attending segregated public schools in the state’s Pike County and, as a boy, was inspired by the work of civil rights activists, including Dr. -

What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective During the Civil Rights Movement?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 5011th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? © Bettmann / © Corbis/AP Images. Supporting Questions 1. What was tHe impact of the Greensboro sit-in protest? 2. What made tHe Montgomery Bus Boycott, BirmingHam campaign, and Selma to Montgomery marcHes effective? 3. How did others use nonviolence effectively during the civil rights movement? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 11th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? 11.10 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE/DOMESTIC ISSUES (1945 – PRESENT): Racial, gender, and New York State socioeconomic inequalities were addressed By individuals, groups, and organizations. Varying political Social Studies philosophies prompted debates over the role of federal government in regulating the economy and providing Framework Key a social safety net. Idea & Practices Gathering, Using, and Interpreting Evidence Chronological Reasoning and Causation Staging the Discuss tHe recent die-in protests and tHe extent to wHicH tHey are an effective form of nonviolent direct- Question action protest. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Guided Student Research Independent Student Research What was tHe impact of tHe What made tHe Montgomery Bus How did otHers use nonviolence GreensBoro sit-in protest? boycott, the Birmingham campaign, effectively during tHe civil rights and tHe Selma to Montgomery movement? marcHes effective? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Create a cause-and-effect diagram tHat Detail tHe impacts of a range of actors Research the impact of a range of demonstrates the impact of the sit-in and tHe actions tHey took to make tHe actors and tHe effective nonviolent protest by the Greensboro Four. -

Public Relations Manager Atlanta Streetcar

CITY OF ATLANTA 55 TRINITY Ave, S.W Kasim Reed ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30335-0300 Sonji Jacobs Dade Mayor Director of Communications City of Atlanta TEL (404) 330-6004 City of Atlanta Public Relations Manager Atlanta Streetcar Title: Public Relations Manager Department: Atlanta Streetcar / Department of Public Works Supervisor: Tim Borchers, Executive Director, Atlanta Streetcar Interested candidates should submit a cover letter and resume to [email protected] no later than Friday, September 13, 2013 at 5:30 p.m. About the Atlanta Streetcar The Atlanta Streetcar is the first phase of a comprehensive, regional streetcar and transit system in the City of Atlanta and the region to address issues of transportation, land use, smart growth, and sustainability while providing last-mile connectivity to riders. The Atlanta Streetcar is a modern, ADA compliant, electrically powered transit system. The streetcar will run for 2.7 miles in the heart of Atlanta’s downtown, business, tourism and convention corridor connecting Centennial Olympic Park area with the vibrant Sweet Auburn and Edgewood Avenue districts. The Atlanta Streetcar project is a cooperative effort by the City of Atlanta, the Atlanta Downtown Improvement District (ADID) and MARTA. The streetcar will run through the heart of Atlanta's business, tourism and convention corridor, bringing jobs and new economic development to the city. Public Relations Manager Overview The Atlanta Streetcar seeks an energetic and articulate Public Relations Director for our press initiatives. The Public Relations Manager will be the primary spokesperson for the Atlanta Streetcar. S/he will work with our staff and partners to build and undertake communications strategies that keep the public informed on the construction and operation of the Streetcar. -

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

CASE STUDY The Montgomery Bus Boycott What objectives, targets, strategies, demands, and rhetoric should a nascent social movement choose as it confronts an entrenched system of white supremacy? How should it make decisions? Peter Levine December 2020 SNF Agora Case Studies The SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University offers a series of case studies that show how civic and political actors navigated real-life challenges related to democracy. Practitioners, teachers, organizational leaders, and trainers working with civic and political leaders, students, and trainees can use our case studies to deepen their skills, to develop insights about how to approach strategic choices and dilemmas, and to get to know each other better and work more effectively. How to Use the Case Unlike many case studies, ours do not focus on individual leaders or other decision-makers. Instead, the SNF Agora Case Studies are about choices that groups make collectively. Therefore, these cases work well as prompts for group discussions. The basic question in each case is: “What would we do?” After reading a case, some groups role-play the people who were actually involved in the situation, treating the discussion as a simulation. In other groups, the participants speak as themselves, dis- cussing the strategies that they would advocate for the group described in the case. The person who assigns or organizes your discussion may want you to use the case in one of those ways. When studying and discussing the choices made by real-life activists (often under intense pres- sure), it is appropriate to exhibit some humility. You do not know as much about their communities and circumstances as they did, and you do not face the same risks. -

Montgomery Bus Boycott and Freedom Rides 1961

MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT AND FREEDOM RIDES 1961 By: Angelica Narvaez Before the Montgomery Bus Boycott vCharles Hamilton Houston, an African-American lawyer, challenged lynching, segregated public schools, and segregated transportation vIn 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality organized “freedom rides” on interstate buses, but gained it little attention vIn 1953, a bus boycott in Baton Rouge partially integrated city buses vWomen’s Political Council (WPC) v An organization comprised of African-American women led by Jo Ann Robinson v Failed to change bus companies' segregation policies when meeting with city officials Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) vVirginia's law allowed bus companies to establish segregated seating in their buses vDuring 1944, Irene Morgan was ordered to sit at the back of a Greyhound Bus v Refused and was arrested v Refused to pay the fine vNAACP lawyers William Hastie and Thurgood Marshall contested the constitutionality of segregated transportation v Claimed that Commerce Clause of Article 1 made it illegal v Relatively new tactic to argue segregation with the commerce clause instead of the 14th Amendment v Did not claim the usual “states rights” argument Irene Morgan v Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) v Supreme Court struck down Virginia's law v Deemed segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional v “Found that Virginia's law clearly interfered with interstate commerce by making it necessary for carriers to establish different rules depending on which state line their vehicles crossed” v Made little -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

The Freedom Rides of 1961

The Freedom Rides of 1961 “If history were a neighborhood, slavery would be around the corner and the Freedom Rides would be on your doorstep.” ~ Mike Wiley, writer & director of “The Parchman Hour” Overview Throughout 1961, more than 400 engaged Americans rode south together on the “Freedom Rides.” Young and old, male and female, interracial, and from all over the nation, these peaceful activists risked their lives to challenge segregation laws that were being illegally enforced in public transportation throughout the South. In this lesson, students will learn about this critical period of history, studying the 1961 events within the context of the entire Civil Rights Movement. Through a PowerPoint presentation, deep discussion, examination of primary sources, and watching PBS’s documentary, “The Freedom Riders,” students will gain an understanding of the role of citizens in shaping our nation’s democracy. In culmination, students will work on teams to design a Youth Summit that teaches people their age about the Freedom Rides, as well as inspires them to be active, engaged community members today. Grade High School Essential Questions • Who were the key players in the Freedom Rides and how would you describe their actions? • Why do you think the Freedom Rides attracted so many young college students to participate? • What were volunteers risking by participating in the Freedom Rides? • Why did the Freedom Rides employ nonviolent direct action? • What role did the media play in the Freedom Rides? How does media shape our understanding -

Atlanta Streetcar System Plan

FINAL REPORT | Atlanta BeltLine/ Atlanta Streetcar System Plan This page intentionally left blank. FINAL REPORT | Atlanta BeltLine/ Atlanta Streetcar System Plan Acknowledgements The Honorable Mayor Kasim Reed Atlanta City Council Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. Staff Ceasar C. Mitchell, President Paul Morris, FASLA, PLA, President and Chief Executive Officer Carla Smith, District 1 Lisa Y. Gordon, CPA, Vice President and Chief Kwanza Hall, District 2 Operating Officer Ivory Lee Young, Jr., District 3 Nate Conable, AICP, Director of Transit and Cleta Winslow, District 4 Transportation Natalyn Mosby Archibong, District 5 Patrick Sweeney, AICP, LEED AP, PLA, Senior Project Alex Wan, District 6 Manager Transit and Transportation Howard Shook, District 7 Beth McMillan, Director of Community Engagement Yolanda Adrean, District 8 Lynnette Reid, Senior Community Planner Felicia A. Moore, District 9 James Alexander, Manager of Housing and C.T. Martin, District 10 Economic Development Keisha Lance Bottoms, District 11 City of Atlanta Staff Joyce Sheperd, District 12 Tom Weyandt, Senior Transportation Policy Advisor, Michael Julian Bond, Post 1 at Large Office of the Mayor Mary Norwood, Post 2 at Large James Shelby, Commissioner, Department of Andre Dickens, Post 3 at Large Planning & Community Development Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. Board Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director of Planning, Department of Planning & Community The Honorable Kasim Reed, Mayor, City of Atlanta Development John Somerhalder, Chairman Joshuah Mello, AICP, Assistant Director of Planning Elizabeth B. Chandler, Vice Chair – Transportation, Department of Planning & Earnestine Garey, Secretary Community Development Cynthia Briscoe Brown, Atlanta Board of Education, Invest Atlanta District 8 At Large Brian McGowan, President and Chief Executive The Honorable Emma Darnell, Fulton County Board Officer of Commissioners, District 5 Amanda Rhein, Interim Managing Director of The Honorable Andre Dickens, Atlanta City Redevelopment Councilmember, Post 3 At Large R. -

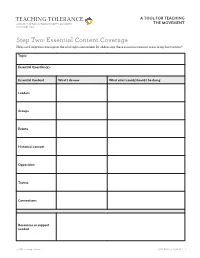

Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How Can I Improve Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement by Addressing These Essential Content Areas in My Instruction?

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: Essential Question(s): Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should I be doing Leaders Groups Events Historical context Opposition Tactics Connections Resources or support needed © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage (SAMPLE) How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should be doing Leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, John Lewis, Roy A. Philip Randolph Wilkins, Whitney Young, Dorothy Height Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Groups Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), National Urban League (NUL), Negro American Labor Council (NALC) The 1963 March on Washington was one of the most visible and influential Some 250,000 people were present for the March Events events of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther on Washington. They marched from the Washington King Jr.