An Index to the Tuneful Yankee and Melody Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 1923) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1923 Volume 41, Number 04 (April 1923) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 41, Number 04 (April 1923)." , (1923). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/700 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. >< T? <1 Theodore Presser Co., Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa. for Child Pianists Teachers Little Albums of Children .ptaliW P“e‘h Send for our interesting Pearls of Instruction in L “Catalogue of Juvenile •ollections makes them children and the Musical Publications This catalogue ha. many helpful The very appearance of these charming wotk8d«Cirfed._Thck.ndertgc9tK nd the covers are just as delightful. little musical gems beh ■ niiMc MOW HELPFUL WITH JUVEN1LES_ TEACHERS WILL FIND THESE / The World of Music Old Rhymes with New Tunes Birthday Jewels THE ETUDE APRIL 1923 Page 219 THE ETUDE AN UP-TO-THE-MINUTE LIST OF 1922-1923 New Music Etude Prize Contest Piano Solos and Duets, Vocal Solos, Sacred and Secular, PIANO SOLOS-VOCAL SOLOS Vocal Duets, Violin and Piano Numbers, ANTHEMS — PART SCfNGS $1,250.00 in Prizes PIANO SOLOS UTE TAKE pipleasure in making the following offer our Etude Prize Contest, being WsKSf of the real value of a contest of this der interest in composition and of of composers. -

March 1941) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 3-1-1941 Volume 59, Number 03 (March 1941) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 59, Number 03 (March 1941)." , (1941). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/252 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. March. THEM ETOPE 1941 Price 25 Cents majqjoizzfimcD !' 1" Pho.00'" ' . ) ) the Sadi e$ Vatutinaf Some of whose interesting songs are i m the catalog of The John Church Co. DOROTHY GAYNOR BLAKE Other outstanding composers represented in The John Church Co. Catalog include Ethelbert Nevin (Mighty Lak' a Rose), Charles Gilbert Spross (Will o’ the Wisp), Oley Speaks (In Maytime ), C. B. Hawley (Sweetest Flower That Blows), Carl Hahn (The Green Cathedral), and many others. Catalogs giving thematic portions of successful John Church Co. song publications cheerfully sent on request. LOUISE SNODGRASS Enchantment Claims Its Own. High (F-c3-flat .60 Star Wishes. High (E-a) .50 Low (c-sharp-F-sharp) .50 ROSADA LAWRANCE Star Wishes. Achal by the Sea. High (d-sharp-a) LILY STRICKLAND Roses. High (d-g) .50 Achal by the Sea. -

Section IX the STATE PAGES

Section IX THE STATE PAGES THE FOLLOWING section presents information on all the states of the United States and the District of Columbia; the commonwealths of Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands; the territories of American Samoa, Guam and the Virgin Islands; and the United Na tions trusteeships of the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and the Republic of Belau.* Included are listings of various executive officials, the justices of the supreme courts and officers of the legislatures. Lists of all officials are as of late 1981 or early 1982. Comprehensive listings of state legislators and other state officials appear in other publications of The Council of State Governments. Concluding each state listing are population figures and other statistics provided by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, based on the 1980 enumerafion. Preceding the state pages are three tables. The first lists the official names of states, the state capitols with zip codes and the telephone numbers of state central switchboards. The second table presents historical data on all the states, commonwealths and territories. The third presents a compilation of selected state statistics from the state pages. *The Northern Mariana Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and the Republic of Belau (formerly Palau) have been administered by the United Slates since July 18, 1947, as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPl), a trusteeship of the United Nations. The Northern Mariana Islands separated themselves from TTPI in March 1976 and now operate under a constitutional govern ment instituted January 9, 1978. -

Herbert Hoover Subject Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf758005bj Online items available Register of the Herbert Hoover subject collection Finding aid prepared by Elena S. Danielson and Charles G. Palm Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1999 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Herbert Hoover 62008 1 subject collection Title: Herbert Hoover subject collection Date (inclusive): 1895-2006 Collection Number: 62008 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 354 manuscript boxes, 10 oversize boxes, 31 card file boxes, 2 oversize folders, 91 envelopes, 8 microfilm reels, 3 videotape cassettes, 36 phonotape reels, 35 phonorecords, memorabilia(203.2 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, writings, printed matter, photographs, motion picture film, and sound recordings, relating to the career of Herbert Hoover as president of the United States and as relief administrator during World Wars I and II. Sound use copies of sound recordings available. Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. Access Boxes 382, 384, and 391 closed. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights Published as: Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace. Herbert Hoover, a register of his papers in the Hoover Institution archives / compiled by Elena S. Danielson and Charles G. Palm. Stanford, Calif. : Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, c1983 For copyright status, please contact Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1962. -

Alex North Collection of Motion Picture Music,1951-1969

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft2j49n6fx No online items Finding Aid for the Alex North Collection of Motion Picture Music , 1951-1969 Collection processed and machine-readable finding aid created by UCLA Library Special Collections staff. UCLA Library Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library UCLA Library Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Arts and Humanities--Music Finding Aid for the Alex North PASC-M 17 1 Collection of Motion Picture Music , 1951-1969 Finding Aid of the Alex North Collection of Motion Picture Music,1951-1969 Collection number: 17 UCLA Library, UCLA Library Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA Contact Information University of California, Los Angeles, Library UCLA Library Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm Processed by: UCLA Library Special Collections staff Date Completed: 1968 Encoded by: Bryan Griest © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Alex North Collection of Motion Picture Music, Date (inclusive): 1951-1969 Collection number: PASC-M 17 Creator: North, Alex Extent: 83 boxes (41.5 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. -

03042021 Clue Program (Final).Pdf

BASED ON THE SCREENPLAY BY JONATHAN LYNN DIRECTED BY DANE CT LEASURE ❘ MARCH 5-13TH WRITTEN BY SANDY RUSTIN. ADDITIONAL MATERIAL BY HUNTER FOSTER, SANDY RUSTIN, AND ERIC PRICE. ADMINISTRATION Interim Program Coordinator Arnold Tunstall, M.F.A. presents Office Manager Alana Weber, M.M. Theatre Coordinator Anna-Jeannine Kemper Dance Coordinator Spring Healy Social Media Manager Madeleine Parks Arts Connections Series Amy Mellinger Photographer John Aylward based on the screenplay by Branding Design Greta Conley and Amanda Ebert JONATHAN LYNN Written by Sandy Rustin Additional Material by Hunter Foster and Eric Price Based on the Paramount Pictures Motion Picture Based on the Hasbro board game CLUE Original Music by David Abbinanti VIDEO PRODUCTION Director Dane CT Leasure, SDC Production Manager Anna-Jeannine Kemper General Manager Juan Eduardo Contreras Barberena, M.A. Stage Manager Cennidie Hall Broadcast Engineer Richard Kent Assistant Stage Manager Arianna Allen Costume Designer Kendra Strickland Production Crew Lighting Designer Patricia Donavan, assisted by the Lighting Design & Technology class Brooke Nappier, Caleb Morgan, Cameron Blenton, Scenic Designer Brian C. Seckfort Connor Vanmaele, De’Abion Strozier, Elek Kitchen, Light Board Operator & Production Assistant Jacen Conlan Jake Herron, Joe Goodman, Jordan Domingo, Kathy Sovak, Michael Matthews, Natalie Savage, Nick McFadden, Sound Engineer Memo Diaz-Capt Nicole Maxhimer, Payton Burkhammer, Tanner Martin Props Master Joseph Fox This show will be performed without intermission. ENSEMBLE CAST Arianna Allen (Ensemble) is a Freshman UA WARNING: Physical Theatre major from Ontario, Ohio who was previously seen as Jinny in The Waves. She The video or audio recording of this performance has spent the last 12 years training as a dancer, by any means is strictly prohibited. -

Jnea1re Organ Bombarde

Jnea1reOrgan Bombarde JOURNAL of the AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN ENTHUSIASTS THE LINK ROBERSON CENTER REGIONAL CONVENTION PREVIEW Wurlitzer Theatre Organ 1 flIll II IIMMlllnllI The modern Theatre Console Organ that combines the grandeur of yesterday with the electronic wizardry of today. Command performance! Wurlitzer combines the classic Horseshoe Design of the immortal Mighty Wurlitzer with the exclusive Total Tone electronic circuitry of today. Knowledge and craftsmanship from the Mighty Wurlitzer Era have produced authentic console dimensions in this magnificent new theatre organ. It stands a part, in an instru ment of its size, from all imitative theatre organ • Dual system of tone generation • Authentic Mighty Wurlitzer Horseshoe Design designs. To achieve its big, rich and electrifying • Authentic voicing of theatrical Tibia and tone, Wurlitzer harmonically "photographed" Kinura originating on the Mighty Wurlitzer pipe organ voices of the Mighty Wurlitzer pipe organ to • Four families of organ tone serve as a standard. The resultant voices are au • Two 61-note keyboards • 25-note pedal keyboard with two 16' and thentic individually, and when combined they two 8' pedal voices augmented by Sustain blend into a rich ensemble of magnificent dimen • Multi-Matic Percussion ® with Ssh-Boom ®, Sustain, Repeat, Attack , Pizzicato, and sion. Then, to crown the accomplishment, we Bongo Percussion incorporated the famous Wurlitzer Multi-Matic • Silicon transistors for minimum maintenance Percussion ® section with exclusive Ssh-Boom ® • Reverb , Slide, Chimes, and Solo controls • Electronic Vibrato (4 settings) that requires no special playing techniques, • Exclusive 2 speed Spectra -Tone @ Sound Pizzi ca to Touch that was found only on larger pipe in Motion • Two-channel solid state amplifiers , 70 watts organs, Chimes and Slide Control .. -

Hurricane Recovery and Resilience Task Force

DRAFT DRAFT USVI SECTOR PRIVATE COMMUNICATIONS: HURRICANE RECOVERY AND RESILIENCE TASK FORCE REPORT 2018 USVI Hurricane Recovery and Resilience Task Force 1 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT This report is dedicated to the Virgin Islanders who lost their lives during and as a result of Hurricanes Irma and Maria, and to their loved ones. No written report could ever accurately or even approximately convey the destruction, loss and pain brought to US Virgin Islands communities by the 2017 hurricanes. These pages also recognize the strength, resilience and resourcefulness of the Virgin Islanders working hard to rebuild and recover. We are Virgin Islands Strong. USVI Hurricane Recovery and Resilience Task Force 3 DRAFT DRAFT Contents Table of Table 4 Report 2018 DRAFT DRAFT Governor’s Address 11 Introduction 12 Executive Summary 18 Hurricanes Irma and Maria 22 Climate Analysis 32 Energy 44 Private Telecom 72 Public Telecom 87 Transportation 100 Water 118 Solid Waste and Wastewater 128 Housing and Buildings 144 Health 160 Vulnerable Categories 182 Education 192 Economy 208 Nonprofit, Philanthropy and Voluntary 226 Organizations Government Response 226 Funding 258 Implementation and Monitoring 268 Table of Table Contents USVI Hurricane Recovery and Resilience Task Force 5 DRAFT DRAFT LIST OF ACRONYMS AMI Advanced Metering Infrastructure ECC Emergency Communication Center ASA Alternative Support Apparatus ED US Department of Education BIT Bureau of Information Technology EDA Economic Development Authority BVI British Virgin Islands EDC Economic Development -

Rage in Eden Records, Po Box 17, 78-210 Bialogard 2, Poland [email protected]

RAGE IN EDEN RECORDS, PO BOX 17, 78-210 BIALOGARD 2, POLAND [email protected], WWW.RAGEINEDEN.ORG Artist Title Label HAUSCHKA ROOM TO EXPAND 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX BLUE NOTEBOOKS, THE 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX SONGS FROM BEFORE 130701/FAT CAT CD ASCENSION OF THE WAT NUMINOSUM 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY COVER UP 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS LTD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE BLOOD 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE DUB YA 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD PRONG POWER OF THE DAMAGER 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKED AND LOADED 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKTAIL MIXXX 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD BERNOCCHI, ERALDO/FE MANUAL 21ST RECORDS CD BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FA BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FAMILY 21ST RECORDS CD FLOWERS OF NOW INTUITIVE MUSIC LIVE IN COLOGNE 21ST RECORDS CD LOST SIGNAL EVISCERATE 23DB RECORDS CD SEVENDUST ALPHA 7 BROS RECORDS CD SEVENDUST CHAPTER VII: HOPE & SORROW 7 BROS RECORDS CD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM COLD A DIFFERENT DRUM MCD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM ON THE ROAD TO WISDOM A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE ALTERNATES AND REMIXES A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE EVENING BELL, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE FALLING STAR, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE MACHINE BOX A DIFFERENT DRUM BOX BLUE OCTOBER ONE DAY SILVER, ONE DAY GOLD A DIFFERENT DRUM CD BLUE OCTOBER UK INCOMING 10th A DIFFERENT DRUM 2CD CAPSIZE A PERFECT WRECK A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMIC ALLY TWIN SUN A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMICITY ESCAPE POD FOR TWO A DIFFERENT DRUM CD DIGNITY -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2019 T 06 Stand: 05. Juni 2019 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2019 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-201811221866 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie sche Katalogisierung von Ausgaben musikalischer Wer- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ke (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ zugrunde. -

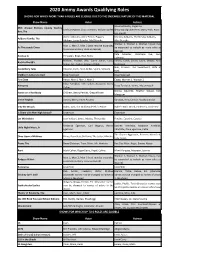

2020 Jimmy Awards Qualifying Roles

2020 Jimmy Awards Qualifying Roles SHOWS FOR WHICH MORE THAN 6 ROLES ARE ELIGIBLE DUE TO THE ENSEMBLE NATURE OF THE MATERIAL Show Name Actor Actress Olive Ostrovsky, Logainne 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Leaf Coneybear, Chip Tolentino, William Barfee Shwartzandgrubenierre, Marcy Park, Rona Bee, The Lisa Peretti Gomez Addams, Uncle Fester, Pugsley Morticia Addams, Wednesday Addams, Addams Family, The Addams, Lucas Beineke, Mal Beineke Alice Beineke Woman 1, Woman 2, Woman 3 (cast may Man 1, Man 2, Man 3 (cast may be expanded As Thousands Cheer be expanded to include as many roles as to include as many roles as desired) desired) Kate Monster, Christmas Eve, Gary Avenue Q Princeton, Brian, Rod, Nicky Coleman Michael, Feargal, Billy, Corey Junior, Corey Tiffany, Cyndi, Eileen, Laura, Debbie, Miss Back to the 80's Senior, Mr. Cocker, Featured Male Brannigan Nun, Prioress, The Sweetheart, Wife of Canterbury Tales Chaucer, Clerk, Host, Miller, Squire, Steward Bath Children's Letters to God Ensemble Cast Ensemble Cast First Date Aaron, Man 1, Man 2, Man 3 Casey, Woman 1, Woman 2 Edna Turnblad, Link Larken, Seaweed, Corny Hairspray Tracy Turnblad, Velma, Motormouth Collins Norma Valverde, Heather Stovall, Kelli Hands on a Hardbody JD Drew, Benny Perkins, Greg Wilhote Mangrum In the Heights Usnavi, Benny, Kevin Rosario Vanessa, Nina, Camila, Abuela Claudia Into the Woods Baker, Jack, The Wolf/Cinderella's Prince Baker's Wife, Witch, Cinderella, Little Red Is There Life After High School? Ensemble Ensemble Les Misérables Jean Valjean, Javert, Marius, Thenardier Fantine, Eponine, Cosette Frederick Egerman, Carl Magnus, Henrik Desiree Armfeldt, Madame Armfeldt, Little Night Music, A Egerman Charlotte, Anne Egerman, Petra The Queen Aggravain, Princess Winnifred, Once Upon a Mattress Prince Dauntless, Sir Harry, The Jester, Minstrel Lady Larkin Prom, The Barry Glickman, Trent Oliver, Mr. -

APPENDICES Appendix A. Islands of the West Indies A.I. Greater Antilles

APPENDICES Appendix A. Islands of the West Indies Caribbean: The Charibee; French : La Mer des Caraibes; Spanish : Mare de las Antillas West Indies: French: Les Antilles; Spanish: Las Antillas; German: Westindischen Inseln Greater Antilles : French: Les Grandes Antilles; Spanish : Antillas Mayores; German: Die Große ren Antillen Lesser Antilles: French: Les Petites Antilles; Spanish: Antillas Manores; German : Die Kleineren Antillen Leeward Islands : French: Les lles Sous-le-Vent; Spanish: Islas de Sotavento Wind ward Islands: French: Les lles Sur-le-Vent; Spanish: Islas de Barlovento The left column contains the islands and in brackets with some of their smaller islands. The right column lists the country or political association. Arehaie or alternate names found in the sources are listed here in brackets. During the early history of the Caribbean, islands were sometimes called by the name of the principal settlement as with San Juan for Puerto Rico, Road Town for Tortola, Bassin (an early name for Christiansted) for Saint Croix, or St. John 's for Antigua. This last may have precipitated Saint John in the U.S. Virgin Islands sometimes being mistaken for Antigua or vice versa. A.I. Greater Antilles Cuba Repüblica de Cuba [Isla de la Juventud (lsle of Pines), Archipielago de Camagüey, Archipielago de Sabana, Cayos de San Filipe, Archipielago de los Canarreos, Archipielago de los Colorodos, Jardines de la Reina] Jamaica Jamaica [Pigeon Island, Morant Cays] [La Jamai"gue, Jamaika, Jamaco] Haiti (western Hispaniola) Republique d'Hai'ti [Ile de la Tortue, Ile Pierre-Joseph, Ile de la [Hayti, Santo Domingo, Saint Gonäve, Grande Cayemite, Ile ä Vache] Domingue, Hispaniola, Espafiola] Dominican Republic (eastern Hispaniola) Repüblica Dominicana [Isla Beata, Isla Catalina, Isla Saona] [Santo Domingo, Saint-Domingue, Haiti, Hispaniola, Espafiola] Puerto Rico Commonwealth ofPuerto Rico (U.S.