Essay I Origin of Jazz Elements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014-2015 Fine Arts Mid-Season Brochure

Deana Martin Photo credit: Pat Lambert The Fab Four NORTH CENTRAL COLLEGE Russian National SEASON Ballet Theatre 2015 WINTER/SPRING Natalie Cole Robert Irvine 630-637-SHOW (7469) | 3 | JA NUARY 2015 Event Price Page # January 8, 9, 10, 11 “October Mourning” $10, $8 4 North Central College January 16 An Evening with Jazz Trumpeter Art Davis $20, $15 4 January 18 Chicago Sinfonietta “Annual Tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” $58, $46 4 January 24 27th Annual Gospel Extravaganza $15, $10 4 Friends of the Arts January 24 Jim Peterik & World Stage $60, $50 4 January 25 Janis Siegel “Nightsongs” $35, $30 4 Thanks to our many contributors, world-renowned artists such as Yo-Yo Ma, the Chicago FEbrUARY 2015 Event Price Page # Symphony Orchestra, Vienna Boys Choir, Wynton Marsalis, Celtic Woman and many more have February 5, 6, 7 “True West” $5, $3 5 performed in our venues. But the cost of performance tickets only covers half our expenses to February 6, 7 DuPage Symphony Orchestra “Gallic Glory” $35 - $12 5 February 7 Natalie Cole $95, $85, $75 5 bring these great artists to the College’s stages. The generous support from the Friends of the February 13 An Evening with Jazz Vocalist Janice Borla $20, $15 5 Arts ensures the College can continue to bring world-class performers to our world-class venues. February 14 Blues at the Crossroads $65, $50 5 February 21 Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn $65, $50 6 northcentralcollege.edu/shows February 22 Robin Spielberg $35, $30 6 Join Friends of the Arts today and receive exclusive benefits. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

For Alto Saxophone and Piano Wade Howles University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music 2017 The nflueI nce of Jazz Elements in Don Freund's Sky Scrapings for Alto Saxophone and Piano Wade Howles University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Composition Commons, and the Ethnomusicology Commons Howles, Wade, "The nflueI nce of Jazz Elements in Don Freund's Sky Scrapings for Alto Saxophone and Piano" (2017). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 113. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/113 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE INFLUENCE OF JAZZ ELEMENTS IN DON FREUND’S SKY SCRAPINGS FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO by Jason Wade Howles A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Paul Haar Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2017 THE INFLUENCE OF JAZZ ELEMENTS IN DON FREUND’S SKY SCRAPINGS FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO J. Wade Howles, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2017 Adviser: Paul Haar Jazz influence surfaces within traditional repertoire for the saxophone more often than other instruments. This is due to the saxophone’s close association with the jazz idiom. -

Paquito D' Rivera

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. PAQUITO D’RIVERA NEA Jazz Master (2005) Interviewee: Paquito D’ Rivera (June 4, 1948 - ) Interviewer: Willard Jenkins with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: June 11, 2010 and June 12, 2010 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 68 pp. Willard: Please give us your full given name. Paquito: I was born Francisco Jesus Rivera Feguerez, but years later I changed to Paquito D’Rivera. Willard: Where did Paquito come from? Paquito: Paquito is the little for Francisco in Latin America. Tito, or Paquito Paco, it is a little word for Francisco. My father’s name was Francisco also, but, his little one was Tito, like Tito Puente. Willard: And what is your date of birth? Paquito: I was born June 4, 1948, in Havana, Cuba. Willard: What neighborhood in Havana were you born in? Paquito: I was born and raised very close, 10 blocks from the Tropicana Cabaret. The wonderful Tropicana Night-Club. So, the neighborhood was called Marinao. It was in the outskirts of Havana, one of the largest neighborhoods in Havana. As I said before, very close to Tropicana. My father used to import and distribute instruments and accessories of music. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] Page | 1 Willard: And what were your parents’ names? Paquito: My father’s name was Paquito Francisco, and my mother was Maura Figuerez. Willard: Where are your parents from? Paquito: My mother is from the Riento Province, the city of Santiago de Cuba. -

Earshot Jazz Festival in November, P 4

A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community Nov 2005 Vol. 21, No. 11 EARSHOT JAZZSeattle, Washington Earshot Jazz Festival in November, P 4 Conversation with Randy Halberstadt, P 21 Ballard Jazz Festival Preview, P 23 Gary McFarland Revived on Film, P 25 PHOTO BY DANIEL SHEEHAN EARSHOT JAZZ A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community ROCKRGRL Music Conference Executive Director: John Gilbreath Earshot Jazz Editor: Todd Matthews Th e ROCKRGRL Music Conference Highlights of the 2005 conference Editor-at-Large: Peter Monaghan 2005, a weekend symposium of women include keynote addresses by Patti Smith Contributing Writers: Todd Matthews, working in all aspects of the music indus- and Johnette Napolitano; and a Shop Peter Monaghan, Lloyd Peterson try, will take place November 10-12 at Talk Q&A between Bonnie Raitt and Photography: Robin Laanenen, Daniel the Madison Renaissance Hotel in Seat- Ann Wilson. Th e conference will also Sheehan, Valerie Trucchia tle. Th ree thousand people from around showcase almost 250 female-led perfor- Layout: Karen Caropepe Distribution Coordinator: Jack Gold the world attended the fi rst ROCKRGRL mances in various venues throughout Mailing: Lola Pedrini Music Conference including the legend- downtown Seattle at night, and a variety Program Manager: Karen Caropepe ary Ronnie Spector and Courtney Love. of workshops and sessions. Registra- Icons Ann and Nancy Wilson of Heart tion and information at: www.rockrgrl. Calendar Information: mail to 3429 were honored with the fi rst Woman of com/conference, or email info@rockrgrl. Fremont Place #309, Seattle WA Valor lifetime achievement Award. com. 98103; fax to (206) 547-6286; or email [email protected] Board of Directors: Fred Gilbert EARSHOT JAZZ presents.. -

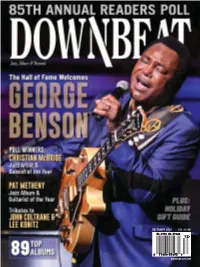

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

8V\..E¢"T <~D~C~'Y

J w,·_" -- ver, and Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, eschewing the refinements and affecta Stream"). They are picking things up where the Parkers, Dolphys, Coltranes, tions of "classical" techniques, returned to jazz roots for inspiration, mainly the Bud Powells, and Scott LaFaros left things some years ago. blues and the mUSic ofthe black church. Into this setting stepped four saxophon ists who were in their own ways to change the face of jazz: Sonny Rollins, John Reprinted from MUSings: The Mustcal World ofGunther Schuller by permission ofOxford University Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Eric Dolphy. All four typified a revolt not only Press. Copyright © 1986 by Gunther Schuller. Cjas~'( L ~):s". <!) A T ~cn~- against the effeteness of"cool" jazz, but even against the "modem jazz» conven c..~I"'''i. ~b ~'- tions, a heritage left in some state of confusion by the untimely death of Charlie ~e~+~8V\..e¢"t <~D~c~'Y Parker. .(tV 8,c.Ls • ""-'.lJ 15 ~\c.':, " t <\ ~ b Both Rollins-with his prodigious facility and almost encyclopedic knowledge \ ) The Jazz Avant-Garde of musical traditions (comparable to a computer memory bank)-and Coltrane with hIS agonizing need to struggle through his musical problems in public-ex pressing the anguish of the artist as a serious quiet man in a violent, crude, and In the early 1960s, the African-American dramatist, novelist, poet, historian, and activist unquiet world-flirted with the avant-garde. But it was Ornette Coleman who in Amiri Baraka (born 1934) contributed many fine essays on jazz and blues to Down 1959 seemed to break all links with the past. -

A Researcher's View on New Orleans Jazz History

2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Format 6 New Orleans Jazz 7 Brass & String Bands 8 Ragtime 11 Combining Influences 12 Party Atmosphere 12 Dance Music 13 History-Jazz Museum 15 Index of Jazz Museum 17 Instruments First Room 19 Mural - First Room 20 People and Places 21 Cigar maker, Fireman 21 Physician, Blacksmith 21 New Orleans City Map 22 The People Uptown, Downtown, 23 Lakefront, Carrollton 23 The Places: 24 Advertisement 25 Music on the Lake 26 Bandstand at Spanish Fort 26 Smokey Mary 26 Milneburg 27 Spanish Fort Amusement Park 28 Superior Orchestra 28 Rhythm Kings 28 "Sharkey" Bonano 30 Fate Marable's Orchestra 31 Louis Armstrong 31 Buddy Bolden 32 Jack Laine's Band 32 Jelly Roll Morton's Band 33 Music In The Streets 33 Black Influences 35 Congo Square 36 Spirituals 38 Spasm Bands 40 Minstrels 42 Dance Orchestras 49 Dance Halls 50 Dance and Jazz 51 3 Musical Melting Pot-Cotton CentennialExposition 53 Mexican Band 54 Louisiana Day-Exposition 55 Spanish American War 55 Edison Phonograph 57 Jazz Chart Text 58 Jazz Research 60 Jazz Chart (between 56-57) Gottschalk 61 Opera 63 French Opera House 64 Rag 68 Stomps 71 Marching Bands 72 Robichaux, John 77 Laine, "Papa" Jack 80 Storyville 82 Morton, Jelly Roll 86 Bolden, Buddy 88 What is Jazz? 91 Jazz Interpretation 92 Jazz Improvising 93 Syncopation 97 What is Jazz Chart 97 Keeping the Rhythm 99 Banjo 100 Violin 100 Time Keepers 101 String Bass 101 Heartbeat of the Band 102 Voice of Band (trb.,cornet) 104 Filling In Front Line (cl. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

June 2015 Vol

A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community June 2015 Vol. 31, No. 06 EARSHOT JAZZSeattle, Washington Morgan Gilkeson & Adriana Giordano: New Faces of Seattle Jams Photo by Daniel Sheehan 2 • Earshot Jazz • June 2015 EaRSHOT JAZZ LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community Executive Director John Gilbreath Money Makes the World Go ‘Round Managing Director Karen Caropepe Programs Assistant Caitlin Peterkin Artists make the art go ‘round. And Earshot Jazz Editors Schraepfer Harvey, art, for most of us, makes life worth Caitlin Peterkin living. Contributing Writers Halynn Blanchard, The issue of artist compensation Levi Gillis, Jeff Janeczko, Bryan Lineberry, has come to the forefront again here Andrew Luthringer, Peter Monaghan in Seattle, and much of the dialogue Calendar Editor Schraepfer Harvey seems to be centered around working Calendar Volunteer Tim Swetonic jazz musicians. Lists are being made, Photography Daniel Sheehan discussions held, and names being Layout Caitlin Peterkin called. Politicians and city offices are Distribution Dan Wight and volunteers showing public support for our art- their pocket, and that the musician’s send Calendar Information to: ists, no doubt while also supporting talented hand is just one more. email [email protected] or the revenue-producing infrastructure But battle lines are sometimes too go to www.earshot.org/Calendar/data/ of our growing city of music. gigsubmit.asp to submit online easily drawn into bi-polar, “us vs. Though the population and econ- them” camps. I would like to propose Board of Directors Ruby Smith Love omy here are in obvious “boom” (president), Diane Wah (vice president), Sally that we all take responsibility, and Nichols (secretary), Sue Coliton, John W. -

Where the Gin Is Cold, but the Piano's Hot Where the Gin Is Cold, but The

03-0106 ETF_46_56 8/25/03 3:53 PM Page 46 THE SAVOY BALLROOM H ARLEM, NEW Y ORK C ITY j Start the car, I know a whoopee spot Where the gin is cold, but the piano’s hot from Overture/All That Jazz “Chicago” movie soundtrack 46 A PRIL© 2002 Sony2003 Music Entertainment,E Inc.NGLISH T EACHING F ORUM 03-0106 ETF_46_56 8/25/03 3:11 PM Page 47 All That Jazzby C. L. Smoak AZZ HAS BEEN LABELED HOT, COOL, SWING, BEBOP AND FUSION, yet it is all these styles and more. Jazz is the irrepressible expression of freedom, liberation, and individual rights through musical improvisation. It is a way people can express themselves and their emotions by means of music. As Art Blakely, noted jazzj drummer and band leader, once said, “Jazz washes away the dust of everyday life.” Jazz has been called the purist expression of American democracy; a music built on individualism and compromise, independence and cooperation. Though it was born in New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 1800s, jazz music was con- ceived over a period of 200 years from world influences including African, Latin Amer- ican, and European. New Orleans, a major seaport of the United States, was the most cosmopolitan city of its time and a melting pot of cultures and nationalities. Even then, the city was known for its openness and vitality. Storyville, a part of town famous for bars and brothels, became the perfect environment for musicians to experiment and improvise with music. By the 1890s there were two distinct styles of music played in New Orleans: ragtime and blues. -

Album Everything's Beautiful

Sydney Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Vol. 9, December 2019 How does Robert Glasper and Miles Davis’ Album Everything’s Beautiful (2016) Move the Legacy of Jazz Rap Forward? ISOBEL SAVULESCU By the late 1980s, hip-hop artists seeking an alternative to mainstream, commercial sounds began to incorporate jazz codes into their music. This led to the conception of the sub-genre known as “jazz rap.” The fusion of these genres brought an elitism to hip-hop records through its association with jazz’s long standing cultural and political capital. Since the twenty-first century, jazz rap as a distinct sub-genre receded into the background of hip-hop and neo-soul music, despite the fact that some artists continue to both lyrically and musically reference jazz. This article begins with a comparative analysis of the evolution of jazz rap over the 1990s, before discussing specifically the jazz codes used in this sub-genre. I then explore how jazz codes emerged in a new and dynamic form in Robert Glasper’s album Everything’s Beautiful (2016), where Glasper re-worked recordings of Miles Davis. I argue that this album uses jazz codes in a different way than jazz rap records of the 1990s, and embodies jazz’s evolution and relevance to the ongoing conversation on what constitutes contemporary music today. Glasper’s samples are not simply static snapshots of jazz as it once was; rather, Glasper integrates recordings of Davis’s music in such a way that it both shapes and is shaped by each track. Davis and Glasper interact in a dynamic way as opposed to the traditionally static way of sampling jazz recordings in hip-hop records; the album represents the two artists as coexisting creative forces.