Ethiopia Food Economy Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Djibouti: Z Z Z Z Summary Points Z Z Z Z Renewal Ofdomesticpoliticallegitimacy

briefing paper page 1 Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn’s Strategic Hub David Styan Africa Programme | April 2013 | AFP BP 2013/01 Summary points zz Change in Djibouti’s economic and strategic options has been driven by four factors: the Ethiopian–Eritrean war of 1998–2000, the impact of Ethiopia’s economic transformation and growth upon trade; shifts in US strategy since 9/11, and the upsurge in piracy along the Gulf of Aden and Somali coasts. zz With the expansion of the US AFRICOM base, the reconfiguration of France’s military presence and the establishment of Japanese and other military facilities, Djibouti has become an international maritime and military laboratory where new forms of cooperation are being developed. zz Djibouti has accelerated plans for regional economic integration. Building on close ties with Ethiopia, existing port upgrades and electricity grid integration will be enhanced by the development of the northern port of Tadjourah. zz These strategic and economic shifts have yet to be matched by internal political reforms, and growth needs to be linked to strategies for job creation and a renewal of domestic political legitimacy. www.chathamhouse.org Djibouti: Changing Influence in the Horn’s Strategic Hub page 2 Djibouti 0 25 50 km 0 10 20 30 mi Red Sea National capital District capital Ras Doumeira Town, village B Airport, airstrip a b Wadis ERITREA a l- M International boundary a n d District boundary a b Main road Railway Moussa Ali ETHIOPIA OBOCK N11 N11 To Elidar Balho Obock N14 TADJOURA N11 N14 Gulf of Aden Tadjoura N9 Galafi Lac Assal Golfe de Tadjoura N1 N9 N9 Doraleh DJIBOUTI N1 Ghoubbet Arta N9 El Kharab DJIBOUTI N9 N1 DIKHIL N5 N1 N1 ALI SABIEH N5 N5 Abhe Bad N1 (Lac Abhe) Ali Sabieh DJIBOUTI Dikhil N5 To Dire Dawa SOMALIA/ ETHIOPIA SOMALILAND Source: United Nations Department of Field Support, Cartographic Section, Djibouti Map No. -

Sustainable Farming Systems in Upland Areas ©APO 2004, ISBN: 92-833-7031-7

From: Sustainable Farming Systems in Upland Areas ©APO 2004, ISBN: 92-833-7031-7 (STM 09-00) Report of the APO Study Meeting on Sustainable Farming Systems in Upland Areas held in New Delhi, India, 15–19 January 2001 Edited by Dr. Tej Partap, Vice Chancellor, CSK Himachal Pradesh Agriculture University, Himachal Pradesh, India Published by the Asian Productivity Organization 1-2-10 Hirakawacho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0093, Japan Tel: (81-3) 5226 3920 • Fax: (81-3) 5226 3950 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.apo-tokyo.org Disclaimer and Permission to Use This document is a part of the above-titled publication, and is provided in PDF format for educational use. It may be copied and reproduced for personal use only. For all other purposes, the APO's permission must first be obtained. The responsibility for opinions and factual matter as expressed in this document rests solely with its author(s), and its publication does not constitute an endorsement by the APO of any such expressed opinion, nor is it affirmation of the accuracy of information herein provided. Note: This title is available over the Internet as an APO e-book, and has not been published as a bound edition. SUSTAINABLE FARMING SYSTEMS IN UPLAND AREAS 2004 Asian Productivity Organization Tokyo Report of the APO Study Meeting on Sustainable Farming Systems in Upland Areas held in New Delhi, India, 15-19 January 2001. (STM-09-00) This report was edited by Dr. Tej Partap, Vice Chancellor, CSK Himachal Pradesh Agriculture University, Himachal Pradesh, India. The opinions expressed in this publication do not reflect the official view of the Asian Productivity Organization. -

Trees of Somalia

Trees of Somalia A Field Guide for Development Workers Desmond Mahony Oxfam Research Paper 3 Oxfam (UK and Ireland) © Oxfam (UK and Ireland) 1990 First published 1990 Revised 1991 Reprinted 1994 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library ISBN 0 85598 109 1 Published by Oxfam (UK and Ireland), 274 Banbury Road, Oxford 0X2 7DZ, UK, in conjunction with the Henry Doubleday Research Association, Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Coventry CV8 3LG, UK Typeset by DTP Solutions, Bullingdon Road, Oxford Printed on environment-friendly paper by Oxfam Print Unit This book converted to digital file in 2010 Contents Acknowledgements IV Introduction Chapter 1. Names, Climatic zones and uses 3 Chapter 2. Tree descriptions 11 Chapter 3. References 189 Chapter 4. Appendix 191 Tables Table 1. Botanical tree names 3 Table 2. Somali tree names 4 Table 3. Somali tree names with regional v< 5 Table 4. Climatic zones 7 Table 5. Trees in order of drought tolerance 8 Table 6. Tree uses 9 Figures Figure 1. Climatic zones (based on altitude a Figure 2. Somali road and settlement map Vll IV Acknowledgements The author would like to acknowledge the assistance provided by the following organisations and individuals: Oxfam UK for funding me to compile these notes; the Henry Doubleday Research Association (UK) for funding the publication costs; the UK ODA forestry personnel for their encouragement and advice; Peter Kuchar and Richard Holt of NRA CRDP of Somalia for encouragement and essential information; Dr Wickens and staff of SEPESAL at Kew Gardens for information, advice and assistance; staff at Kew Herbarium, especially Gwilym Lewis, for practical advice on drawing, and Jan Gillet for his knowledge of Kew*s Botanical Collections and Somalian flora. -

Forest Soils of Ethiopian Highlands: Their Characteristics in Relation to Site History Studies Based on Stable Isotopes

Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae SlLVESTRIA 147 Ax y* > uU z <$> * SLU Forest Soils of Ethiopian Highlands: Their Characteristics in Relation to Site History Studies based on stable isotopes Zewdu Eshetu -'•« V i $ V • *• - / ‘ *. * < * J »>•>. ; > v ‘ U niversity of Agricultural S c ien c es JL0>" ""’'■t ■SLU, Forest soils of Ethiopian highlands: Their characteristics in relation to site history.Studies based on stable isotopes. Zewdu Eshetu Akademisk avhandling som för vinnande av skoglig doktorsexamen kommer att offentligen försvaras i hörsal Björken, SLU, fredagen den 9 juni, 2000, kl. 13.00. Abstract Isotopic composition and nutrient contents of soils in forests, pastures and cultivated lands were studied in Menagesha and Wendo-Genet, Ethiopia, in order to determine the effects of land use changes on soil organic matter, the N cycle and the supply of other nutrients. In the Menagesha forest, which according to historical accounts was planted in the year 1434-1468, 5I3C values at > 20 cm soil depth of from-23 to -17%oand in the surface layers of from-27 to -24%o suggest that C4 grasses or crops were important components of the past vegetation. At Wendo-Genet, the 5'3C values in the topsoils of from-23 to -16%o and in the > 20 cm of from-16 to -14%o indicated more recent land use changes from grassland to forest. At Menagesha, 5I5N values shifted from -8.8%oin the litter to +6.8%o in the > 20 cm. The low 5I5N in the litter (-3%o) and topsoils(0%o) suggest a closed N cycle at Menagesha. -

A History of Domestic Animals in Northeastern Nigeria

A history of domestic animals in Northeastern Nigeria Roger M. BLENCH * PREFATORY NOTES Acronyms, toponyms, etc. Throughout this work, “Borna” and “Adamawa” are taken ta refer to geographical regions rather than cunent administrative units within Nigeria. “Central Africa” here refers to the area presently encompas- sed by Chad, Cameroun and Central African Republic. Orthography Since this work is not wrîtten for specialised linguists 1 have adopted some conventions to make the pronunciation of words in Nigerian lan- guages more comprehensible to non-specialists. Spellings are in no way “simplified”, however. Spellings car-rbe phonemic (where the langua- ge has been analysed in depth), phonetic (where the form given is the surface form recorded in fieldwork) or orthographie (taken from ear- lier sources with inexplicit rules of transcription). The following table gives the forms used here and their PA equivalents: This Work Other Orthographie IPA 11989) j ch tî 4 d3 zl 13 hl, SI Q Words extracted from French sources have been normalised to make comparison easier. * Anthropologue, African Studies Cenfer, Universify of Cambridge 15, Willis Road, Cambridge CB7 ZAQ, Unifed Kingdom. Cah. Sci. hum. 37 (1) 1995 : 787-237 182 Roger BLENCH Tone marks The exact significance of tone-marks varies from one language to ano- ther and 1 have used the conventions of the authors in the case of publi- shed Ianguages. The usual conventions are: High ’ Mid Unmarked Low \ Rising ” Falling A In Afroasiatic languages with vowel length distinctions, only the first vowel of a long vowel if tone-marked. Some 19th Century sources, such as Heinrich Barth, use diacritics to mark stress or length. -

Table 2. Geographic Areas, and Biography

Table 2. Geographic Areas, and Biography The following numbers are never used alone, but may be used as required (either directly when so noted or through the interposition of notation 09 from Table 1) with any number from the schedules, e.g., public libraries (027.4) in Japan (—52 in this table): 027.452; railroad transportation (385) in Brazil (—81 in this table): 385.0981. They may also be used when so noted with numbers from other tables, e.g., notation 025 from Table 1. When adding to a number from the schedules, always insert a decimal point between the third and fourth digits of the complete number SUMMARY —001–009 Standard subdivisions —1 Areas, regions, places in general; oceans and seas —2 Biography —3 Ancient world —4 Europe —5 Asia —6 Africa —7 North America —8 South America —9 Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds —001–008 Standard subdivisions —009 History If “history” or “historical” appears in the heading for the number to which notation 009 could be added, this notation is redundant and should not be used —[009 01–009 05] Historical periods Do not use; class in base number —[009 1–009 9] Geographic treatment and biography Do not use; class in —1–9 —1 Areas, regions, places in general; oceans and seas Not limited by continent, country, locality Class biography regardless of area, region, place in —2; class specific continents, countries, localities in —3–9 > —11–17 Zonal, physiographic, socioeconomic regions Unless other instructions are given, class -

Martial Race Ideology and the Experience of Highland Scottish and Irish Regiments in Mid-Victorian Conflicts, 1853-1870 Adam Spivey East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2017 Friend or Foe? Martial Race Ideology and the Experience of Highland Scottish and Irish Regiments in Mid-Victorian Conflicts, 1853-1870 Adam Spivey East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Spivey, Adam, "Friend or Foe? Martial Race Ideology and the Experience of Highland Scottish and Irish Regiments in Mid-Victorian Conflicts, 1853-1870" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3216. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3216 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Friend or Foe? Martial Race Ideology and the Experience of Highland Scottish and Irish Regiments in Mid-Victorian Conflicts, 1853-1870 ________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _______________________ by Adam M. Spivey May 2017 ________________________ Dr. John Rankin, Chair Dr. Stephen Fritz Dr. William Douglas Burgess Keywords: British Empire, Martial Race, Highland Scots, Fenian, Indian Mutiny, Crimean War ABSTRACT Friend or Foe? Martial Race Ideology and the Experience of Highland Scottish and Irish Regiments in Mid-Victorian Conflicts, 1853-1870 by Adam M. -

The Effects of Land Use on Stream

THE EFFECTS OF LAND USE ON STREAM COMMUNITIES IN HIGHLAND TROPICAL NIGERIA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand by Danladi Mohammed Umar University of Canterbury 2013 Contents Acknowledgements ...........................................................................................................iv Abstract ..............................................................................................................................vi Chapter 1 General introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 2 Illustrated guide to freshwater invertebrates of the Mambilla Plateau .............................. 24 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 24 Methods.............................................................................................................................. 25 Freshwater invertebrates .................................................................................................... 29 Taxonomic classifications .................................................................................................. 31 Key to the aquatic macroinvertebrates of the Mambilla Plateau ....................................... 32 Chapter 3 Response of benthic invertebrates to a land use gradient in tropical highland streams ... 103 Introduction -

Agriculture and Conservation in the Hills and Uplands

AGRICULTUREAND CONSERVATION IN THEHILLS AND UPLANDS INSTITUTEof TERRESTRIALECOLOGY NATURALENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL á Natural Environment Research Council Agriculture and conservation in the hills and uplands ITE symposium no. 23 Edited by M BELL and R GH BUNCE ITE, Merlewood Research Station INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY Printed in Great Britain by Galliard (Printers) Ltd, Great Yarmouth, Norfolk NERC Copyright 1987 Published in 1987 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Merlewood Research Station GRANGE-OVER-SANDS Cumbria LA11 6JU BRITISHLIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Agriculture and conservation in the hills and uplands (ITE symposium, ISSN 0263-8614: no. 23) 1. Nature conservation - Great Britain 3. Landscape conservation - Great Britain I. Bell, M II. Bunce, R G H III. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology. V. Series 333. 76160941 OH77. G7 ISBN 1 870393 03 1 COVER ILLUSTRATION North Pennine Dales Environmentally Sensitive Area, a landscape created by farming, retaining semi-natural vegetation and hay meadows whereon traditional management practices are crucial to the maintenance of floral diversity. New national and European Commission grants can assist conservation and the small farm structure which underpins the area. It is no longer tenable to consider farm, conservation or rural social policies in isolation (Photograph R Scott) The Institute of Terrestrial Ecologywas established in 1973. from the former Nature Conservancy's research stations and staff, joined later by the Institute of the Tree Biology and Culture Centre of Algae and Protozoa. ITE contributes to. and draws upon, the collective knowledge of the 14 sister institutes which make up the Natural Environment Research Council, spanning all the environmental sciences. The Institute studies the factors determining the structure, composition and processes of land and freshwater systems, and of individual plant and animal species. -

Ethiopia. Conservation Can No Longer Be Viewed Separately from Development: a Nationwide Strategy of Conservation Based Development Is Needed

AG:UTF/ETH/O37/ETH Final Report, Vol, I ETHIOPIAN FUNDS-IN-TRUST ETHIOPIAN HIGHLANDS RECLAMATION STUDY ETHIOPIA FINAL REPORT Volume 1 Report prepared for the Government of Ethiopia by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 1986 AG:UTF/ETH/037/ETH Final Report, Vol. 1 ETHI.OPIAN FUNDS-IN-TRUST ETHIOPIAN HIGHLANDS RECLAMATION STUDY ETHIOPIA FINAL REPORT Volume 1 Report prepared for the Government of Ethiopia by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 1986 The designations employed and the presentation of the material and maps in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The compilation of this report, with itscoverage of the different sectors and activities relevant to the development of an areaas large and diverse as the Ethiopian highlands, would not have beenpossible within the two-year period since the study became operational without the assistance of many people. Unfortunately itis not possibleto name individually the several hundred persons who have contributed to the EHRS, sometimes at much inconvenience to themselves, but the team acknowledges with gratitude its indebtedness to all those persons and institutions who have assistedtheproject by providing information, advice, suggestions, comments on working papers and logistical support and facilities. -

The Geology and Hydrogeology of Springs on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada: an Overview Fred E

Document generated on 10/02/2021 2:48 a.m. Atlantic Geology Journal of the Atlantic Geoscience Society Revue de la Société Géoscientifique de l'Atlantique The geology and hydrogeology of springs on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada: an overview Fred E. Baechler, Heather J. Cross and Lynn Baechler Volume 55, 2019 Article abstract Cape Breton Island springs have historically played a role in developing URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1060417ar potable water supplies, enhancing salmonid streams, creating thin-skinned DOI: https://doi.org/10.4138/atlgeol.2019.004 debris flows, as well as mineral and hydrocarbon exploration. Cape Breton Island provides a hydrogeological view into the roots of an ancient mountain See table of contents range, now exhumed, deglaciated and tectonically inactive. Exhumation and glaciation over approximately 140 Ma since the Cretaceous are of particular relevance to spring formation. A total of 510 springs have been identified and Publisher(s) discussed in terms of hydrological regions, flow, temperature, sphere of influence, total dissolved solids, pH and water typing. Examples are provided Atlantic Geoscience Society detailing characteristics of springs associated with faults, karst, salt diapirs, rockfall/alluvial systems and debris avalanche sites. Preliminary findings from ISSN a monitoring program of 27 springs are discussed. Future research should focus on identifying additional springs and characterizing associated 0843-5561 (print) groundwater dependent ecosystems. Incorporating springs into the provincial 1718-7885 (digital) groundwater observation well monitoring program could facilitate early warning of drought conditions and other impacts associated with changing Explore this journal climate. Cite this article Baechler, F., Cross, H. -

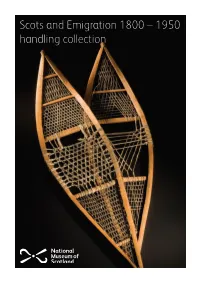

Scots and Emigration 1800 – 1950 Handling Collection

Scots and Emigration 1800 – 1950 handling collection . Scots and Emigration 1800 – 1950 handling collection Teachers notes Welcome to the National Museum of Scotland. Our Emigration handling collection contains 9 original artefacts and 9 written sources from our collection and we encourage everyone to enjoy looking at and touching the artefacts to find out all about them. These notes include: • Background information on emigration from Scotland, including the Highland Clearances in the 19th century. • Details about each item. • Ideas for questions, things to think about and discuss with your group. NMS Good handling guide The collection is used by lots of different groups so we’d like your help to keep the collection in good condition. Please follow these guidelines for working with the artefacts and talk them through with your group. 1 Always wear gloves when handling the artefacts (provided) 2 Always hold artefacts over a table and hold them in two hands 3 Don’t touch or point at artefacts with pencils, pens or other sharp objects 4 Check the artefacts at the start and the end of your session 5 Please report any missing or broken items using the enclosed form National Museum of Scotland Teachers’ Resource Pack Scots and Emigration 1800 – 1950 handling collection What is emigration? • Emigration involves individuals or groups of people leaving their country of origin to settle in another. This may be for personal, social or economic reasons, or to escape hardship or persecution. • Immigration is the arrival and settlement into a country or population of people from other countries. Scots and emigration • For hundreds of years, Scots have left this country to live and work abroad.