Borderline Features, Rejection Sensitivity, and Romantic Relationships: a Daily Diary Study of Romantic Partners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masculinity of Men Communicating Abuse Victimization

Male Victimization 1 Running Head: MALE VICTIMIZATION Masculinity of Men Communicating Abuse Victimization Jessica J. Eckstein1, Ph.D. May 5th, 2010 Assistant Professor, Communication Department Western Connecticut State University 1 This paper is “in press” in the journal of Culture, Society, and Masculinities. The manuscript is based on an earlier version of the paper, “Constructing Gendered Victimization: Examining the Narratives of Men Experiencing Violence from Female Partners,” presented at the 2007 annual conference of National Communication Association, Chicago, IL. Male Victimization 2 Abstract This study explored, through in-depth interviews, the experiences of men sexually, psychologically, and/or physically victimized by female romantic partners. Men‟s narratives were analyzed to determine how masculinity and construction of victim-identities were related. Results show that abused men construed victimization as precipitated internally through self- blame and externally via societal-blame. Gendered masculinity was demonstrated for most men in the form of hegemonic-striving via complicit rationalizations; however, a minority of men constructed victimization in terms of protest masculinity. KEY WORDS: Masculinity, Hegemony, Intimate partner violence, Men, Victimization Male Victimization 3 Masculinity of Men Communicating Abuse Victimization Each year, 3.2 million men in the United States are victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). Male IPV victimization, while not as common as female victimization, is a serious problem with its own set of identity issues for male victims. Unfortunately, men‟s victimization from female partners receives comparatively limited scholarly attention (George, 2003). The goal of this study was to explore, through in-depth interviews, male IPV victims‟ communication of gender identities. -

Workplace Bullying Legislation That Would Allow Workers to Sue for Harassment Without Requiring a Showing of Discrimination

Workplace-Bullying Laws on the Horizon? By Roy Maurer Since 2003, 25 states have introduced workplace bullying legislation that would allow workers to sue for harassment without requiring a showing of discrimination. Critics contend that these laws would encourage frivolous lawsuits. Could they protect workers from bullying while not opening up employers to scores of meritless claims or imposing a civility code on the workplace? “In fact, workplace bullying may lead to the boldest proposed change in U.S. employment law since the passage of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act,” said Lori Armstrong Halber, a partner in the Philadelphia office of Fisher & Phillips. “We all agree with the concept that there shouldn’t be jerks in the workplace, but the issue is whether we can legislate that,” said Rick Grimaldi, a partner in the Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., offices of Fisher & Phillips. “The whole concept is difficult to get your head around when you think about how expansive this could be. Every disgruntled employee becomes a potential plaintiff.” Presently, bullying by itself does not violate Title VII or any other anti-discrimination law. Employees can sue companies for creating a “hostile work environment,” which can include bullying as harassment, but the harassment usually is tied to a protected category, such as race, sex, religion or national origin. Anti-bullying advocates are pushing legislation to protect workers who are not in a protected class. Other countries—England, Sweden, Australia—already have such laws. But how do you define bullying? asked Armstrong Halber. “In an effort to avoid litigation, employers would be mediating all sorts of employee interactions. -

Research Into Cyberbullying and Cyber Victimisation

Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2007, 23(4), 435-454 Bullying in the new playground: Research into cyberbullying and cyber victimisation Qing Li University of Calgary This study examines the nature and extent of adolescents’ cyberbullying experiences, and explores the extent to which various factors, including bullying, culture, and gender, contribute to cyberbullying and cyber victimisation in junior high schools. In this study, one in three adolescents was a cyber victim, one in five was a cyberbully, and over half of the students had either experienced or heard about cyberbullying incidents. Close to half of the cyber victims had no idea who the predators were. Culture and engagement in traditional bullying were strong predictors not only for cyberbullying, but also for cyber victimisation. Gender also played a significant role, as males, compared to their female counterparts, were more likely to be cyberbullies. Cyberbullying and cyber victimisation School bullying has been widely recognised as a serious problem and it is particularly persistent and acute during junior high and middle school periods (National Center for Educational-Statistics, 1995). In the USA, “up to 15% of students … are frequently or severely harassed by their peers. … Only a slim majority of 4th through 12th graders … (55.2%) reported neither having been picked on nor picking on others” (Hoover & Olsen, 2001). Universally, bullying is reported as a significant problem in many countries of the world including European countries, North America, and Japan (Smith et al., 1999), suggesting that bullying may play a important role in adolescents’ life in many societies. More importantly, it is reported that in many cases of school shootings, the bully played a major role (Dedman, 2001; Markward, Cline & Markward, 2002). -

Neural and Behavioral Effects of Being Excluded by the Targets of a Witnessed Social Exclusion

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Psychology 2014 Neural and Behavioral Effects of Being Excluded by the Targets of a Witnessed Social Exclusion Kaitlin R. Dunn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/psych_honproj Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Dunn, Kaitlin R., "Neural and Behavioral Effects of Being Excluded by the argetsT of a Witnessed Social Exclusion" (2014). Honors Projects. 164. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/psych_honproj/164 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Running Head: WITNESSING AND EXPERIENCING SOCIAL EXCLUSION 1 Neural and Behavioral Effects of Being Excluded by the Targets of a Witnessed Social Exclusion Kaitlin R. Dunn Illinois Wesleyan University Running Head: WITNESSING AND EXPERIENCING SOCIAL EXCLUSION 2 Abstract The consequences of social exclusion can be extremely detrimental to physical and emotional well being, ranging from mild distress to extreme violence and aggression. Research findings indicate that witnessing exclusion is just as common as experiencing exclusion and can invoke similar levels of distress. -

A Male Victim's Experience of Gaslighting and His Legal Fight to See

A male victim’s experience of gaslighting and his legal fight to see his son This is the story of a man who experienced domestic abuse, as written by himself, hoping that other men with similar experiences will recognise the signs and get help. The names of the people involved have been changed. The beginning of the relationship During the start of the relationship with Jenny, she portrayed herself as a loving mother and girlfriend. She had made huge statements about abuse from the father of her children and I formed a strong bond with them very quickly. Jenny starts to manipulate James Jenny was very public about how amazing I was with her kids and made a huge deal about me being a great stepfather. What I didn’t realise at the time was she was completely love-bombing me; she had also already started chipping away and undermining me. However, due to my naivety and trying to see the good in someone, I went along with it. When she was pregnant with my son there were several isolated incidents of abuse. I naively put this down to the pregnancy and to the horrific experiences from her past relationship she had told me about. In hindsight, Jenny undermined me, put me down, used gaslighting and emotionally and financially abused me. She used these small isolated incidents with love-bombing, so at first the abuse was bearable, as I was naive to this type of behaviour. Gaslighting Jenny started changing the way I was thinking. When her behaviour was wrong, she would convince me that it was me who needed to change. -

Experiences of Children of Parents with Personality Disorders Miriam

I May be Slightly Broken i I May be Slightly Broken: Experiences of Children of Parents with Personality Disorders Miriam Tepper, BSW, MSW Candidate Supervising Faculty Member: Regina Praetorius, PhD, LMSW-AP December 2019 I May be Slightly Broken ii Abstract Child abuse is defined as any emotional, psychological or physical abuse or neglect inflicted on a child, that causes distress and impaired functioning for that child. A child’s caregiver was reported to be the main source of child abuse, with increasing chances if the parent struggles with a mental health disorder and or co-morbid substance use disorder or physical issues. The mental health issues that have been noted as a significant source of abuse include a parent who struggles with a personality disorder including borderline personality disorder (BPD) and narcissistic personality disorder (NPD). These personality disorders stem from years of negative childhood beliefs and feedback with an underlying character trait of emotional dysregulation (ED). Research has noted that individuals experiencing abuse from a parent with NPD or BPD struggled to not only seek help, but were unable to complete their recommended treatment intervention due to many obstacles. Two of the main obstacles reported from adult survivors who did reach for help was losing their family members because they sought assistance and the individual not knowing that what he/she experienced as a child was considered abuse. Key words: borderline personality disorder (BPD), narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), help seekers, non-help seekers, cycle of abuse. I May be Slightly Broken iii Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….1 Prevalence of Childhood Abuse and or Neglect…………………………………………………..1 Typical Characteristics of Abusers………………………………………………………………..1 Abuse as a Maladaptive Coping Mechanism and Personality Disorders…………………………2 Cyclical Possibility of Victims Becoming Abusers…………………...…………………………. -

Two New Faculty Members in Purdue's Creative Writing Program

on the cover P A G E 4 The year 1953 was historic for the College of Liberal Arts, for it was the year that the School of Science was renamed the School of Science, Education, and Humanities. This move acknowledged Remembering Purdue the growing interest in the humanities and social sciences and their place as legitimate fields of study within the University. Alumni reflect on their favorite Purdue memories The lifestyle and environment of a student in 1953 was drastically different from that of a current student. Student essentials in 2006 may include a cell phone, laptop, and iPod, whereas a student in 1953 probably considered pencil and paper adequate supplies. Taking a look back, in 1953 … • Chart toppers include Perry Como, Dean Martin, and Teresa Brewer. P A G E • The first color television sets go on sale for about $1,175. 6 • The IBM 650 computer is introduced. • The best-selling car is the Volkswagen Beetle at $1,495. • The Greatest Show on Earth wins the 1953 Academy Award What’s in a Name? for Best Picture. • The first successful open heart surgery is performed. Evolution of liberal arts at Purdue • New York City adopts three-color traffic lights. • The first issue of TV Guide magazine hits the newsstands on April 3 in 10 cities with a circulation of 1,560,000. • The airwaves boast 2,357 AM radio, 616 FM radio, and 125 TV stations. • Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower is inaugurated President of the United States. P A G E • Soviet ruler Joseph Stalin dies. 10 • Lucille Ball gives birth to Desi Arnaz Jr. -

F. Catanzariti, Oct06

ACC Docket 84 April 2010 An employee in your company approaches you and tells you he is ter- rified to come to work. He explains that he is constantly the sub- ject of social ostracism, vulgar language and dismissive and rude behavior from both supervisors and coworkers. Despite producing quality work, he is criticized on a regular basis for his performance. He does not believe, however, that this treatment is because of race, gender, age or any other protected characteristic. Is this employee sim- ply disgruntled, or just too sensitive and unable to handle the rigorous nature of today’s corporate climate? As we all know, times are tough and competition among coworkers and supervi- sors in corporate America is not uncommon. Some What Employers Should companies may even en- Do to Address Bullying courage such behavior by overemphasizing that Behavior in the Workplace competitiveness. How- ever, the behavior that your employee describes may be more than workplace competition, and failing to deal with the issue promptly may have a negative impact on your com- pany — both legally and financially. By Carol Rick Gibbons, Rodney A. Satterwhite and Latoya C. Asia ACC Docket 85 April 2010 employee morale and performance, and What is Workplace Bullying? Carol riCk Gibbons is an An emerging risk for companies today associate general counsel your company’s culture. for Capital one Financial is a surprisingly common phenomenon Corporation in richmond, Va, known as workplace bullying. While there where she leads the legal de- Workplace Bullying and Its Impact partment’s employment and benefits group. is no standard definition of workplace Gibbons is the chair of the Employment and on the Workplace bullying, the expression is commonly used labor law Committee and a member of the Workplace bullying is becoming more WMaCCa board. -

Peer Victimization and the Development of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms: the Roles of Stress Physiology and Gender Leigh Ann Holterman University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2016 Peer Victimization and the Development of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms: The Roles of Stress Physiology and Gender Leigh Ann Holterman University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Developmental Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Holterman, Leigh Ann, "Peer Victimization and the Development of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms: The Roles of Stress Physiology and Gender" (2016). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 460. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/460 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PEER VICTIMIZATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF ANXIETY AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS: THE ROLES OF STRESS PHYSIOLOGY AND GENDER A Thesis Presented by Leigh Ann Holterman to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in Psychological Science January, 2016 Defense Date: October 21, 2015 Thesis Examination Committee: Dianna “Annie” Murray-Close, Ph.D., Advisor Patricia Prelock, Ph.D., CCC-SLP, Chairperson Jamie Abaied, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College Abstract The overall goal of the current study was to determine whether experiences of relational and physical victimization were related to anxiety and depressive symptoms in a sample of emerging adults. This study also investigated whether these associations were moderated by gender, as well as by sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) reactivity to peer stress. -

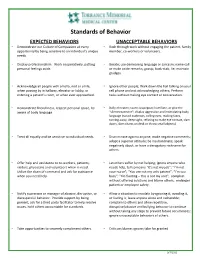

Standards of Behavior

Standards of Behavior EXPECTED BEHAVIORS UNACCEPTABLE BEHAVIORS • Demonstrate our Culture of Compassion at every • Rush through work without engaging the patient, family opportunity by being sensitive to an individual’s unique member, co-workers or volunteers. needs. • Display professionalism. Work cooperatively, putting • Berate; use demeaning language or sarcasm; name call personal feelings aside. or make snide remarks; gossip; back-stab; lie; maintain grudges. • Acknowledge all people with a hello, nod or smile, • Ignore other people; Walk down the hall talking on your when passing by in hallway, elevator or lobby, or cell phone and not acknowledging others; Perform entering a patient’s room, or when ever approached. tasks without making eye contact or conversation. • Demonstrate friendliness, respect personal space, be • Bully; threaten; taunt; scapegoat; humiliate, or give the aware of body language. “silent treatment”; display aggressive and intimidating body language (raised eyebrows, rolling eyes, making faces, turning away, deep sighs, refusing to make eye contact, slam doors, slam charts on desk or throw small objects). • Treat all equally and be sensitive to individual needs. • Discriminate against anyone; make negative comments; adopt a superior attitude; be insubordinate; speak negatively about, or have a derogatory nickname for others. • Offer help and assistance to co-workers, patients, • Let others suffer by not helping; ignore anyone who visitors, physicians and volunteers when in need. needs help, tell someone “It’s not my job”; “I’m not Utilize the chain of command and ask for assistance your nurse”; “You are not my only patient”; “I’m too when you need help. busy”; “I’m floating – this is not my unit”; complain without offering solutions and blame others; endanger patient or employee safety. -

Self Esteem and Self Confidence As Self Preservation © Copyright Unrulynerdgirl

Self Esteem and Self Confidence as Self Preservation © copyright UnrulyNerdGirl (Please do not reproduce or share this material as it is intended as support for workshop attendees, and does not represent the whole) Note ● I am not a mental or physical health care professional, and can not provide professional advice in terms of coping with mental or emotional trauma. ● I can only provide you with what I have learned through lived experience, and my own research. It is my hope that both of these will be of benefit to you, and perhaps make your journey a little easier. ● If you are in need of counselling or professional help, I would urge you to seek it - with no shame or judgement - in case it might assist you in walking your best path. Four Human Affects ● Shame - I am bad, falling short of societal standards ● Guilt - I did something, falling short of own self standards ● Embarrassment - fleeting, happens to everyone ● Humiliation - didn’t deserve it, usually brought on by others What is Shame? ● a painful feeling of distress caused by the consciousness of wrong or foolish behaviour ● the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing we are flawed, and therefore unworthy of love and belonging - something we’ve experienced, done, or failed to do makes us unworthy of connection Shame leaves one feeling alone and isolated. What Does Shame Feel Like? ● Hot ● Perspiration ● Tingling ● Tunnel Hearing ● Fight/flight/freeze/fawn (friend)/flop/fuck ● Anger ● Numbness ● Crying ● Choked up ● Stomach tightens ● Face flush ● Dry mouth ● Shutting down ● Racing heart ● Mind goes blank ● Can’t hold a gaze The physical/mental/emotional/psychological reactions to shame are the same as the reactions to trauma. -

Employee Silence: Investigation of Dimensionality

EMPLOYEE SILENCE: INVESTIGATION OF DIMENSIONALITY, DEVELOPMENT OF MEASURES, AND EXAMINATION OF RELATED FACTORS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad T. Brinsfield ***** The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor Roy J. Lewicki, Advisor Professor Howard J. Klein ______________________ Professor Steffanie L. Wilk Advisor Labor and Human Resources Graduate Program Copyright by Chad T. Brinsfield 2009 ABSTRACT The intentional withholding of information by employees at work has been linked to many important individual and organizational outcomes. Only in recent years, however, has the concept of employee silence as meaningful beyond the absence of speaking-up become an important area of inquiry in the organizational sciences. Notwithstanding this emerging interest, relatively little is known about the underlying nature of this abstract phenomenon. In an attempt to increase our understanding of this phenomenon, a model of employee silence is presented and three related studies are conducted. The proposed model illustrates proximal and component factors of employee silence and their proposed relationships. This model adapts elements of cybernetic control theory (Carver & Scheier, 1982) and psychological field theory (Lewin, 1936, 1943) to explain different aspects of the manifestation of employee silence at different levels of abstraction. The three studies which follow are designed to: (a) investigate the nature and dimensionality of the motives for employee silence, (b) develop survey measures of employee silence based on these dimensions, and (c) use these new measures to investigate factors related to the manifestation of the various dimensions of employee silence.