Commonwealth Forests 2010 an Overview of the Forests and Forestry Sectors of the Countries of the Commonwealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SFI 2020 Annual Report

SUSTAINABLE FORESTRY INITIATIVE 2YEARS SFI-00001 1995-20205 BETTER CHOICES FOR THE PLANET 2020 SFI PROGRESS REPORT 18-month calendar July 2020–December 2021 SUSTAINABLE FORESTRY INITIATIVE 2YEARS SFI-00001 1995-20205 IT IS CRITICAL THAT WE WORK TOGETHER TO ENSURE THE SUSTAINABILITY OF OUR PLANET. People and organizations are seeking solutions that don’t just reduce negative impacts but ensure positive contributions to the long-term health of people and the planet. SFI-certified forests and products are powerful tools to achieve shared goals such as climate action, reduced waste, conservation of biodiversity, education of future generations, and sustainable economic development. SFI PROVIDES PRACTICAL, SCALABLE SOLUTIONS FOR MARKETS AND COMMUNITIES WORKING TO PURSUE THIS GROWING COMMITMENT TO A SUSTAINABLE PLANET. When companies, consumers, educators, community, and sustainability leaders collaborate with SFI, they are making active, positive choices to achieve a sustainable future. Our mission is to advance sustainability through forest-focused collaborations. For 25 years, SFI has been a leader in sustainable forest management through our standards. In recent years, we have built on our successes and evolved into a solutions-oriented sustainability organization that addresses local, national, and global challenges. Our recently updated mission, to advance sustainability through forest-focused collaborations, reflects this focus. Climate change, biodiversity, strength in diversity, clean water, the future of our youth, the importance of a walk in the forest, and the sustainability and resilience of our communities—these are some of the important issues that the SFI community is working to address. Thank you for We also realized that we will need a new generation of leaders to help us tackle the future challenges being a part of facing our planet. -

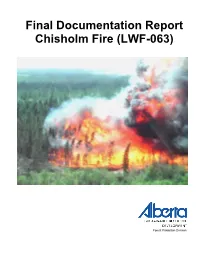

Final Documentation Report Chisholm Fire (LWF-063)

Final Documentation Report Chisholm Fire (LWF-063) Forest Protection Division TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 OVERVIEW.................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Context ................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Chisholm Community............................................................................................. 2 1.3 Documentation Team.............................................................................................. 3 Section 1.0 1 1.0 OVERVIEW 1.1 CONTEXT Over the past decade, fire seasons in North America have generally increased in both length and severity. In both 2000 and 2001, the fire season in Alberta was officially declared on March 1, one month earlier than all previous years on record. Coinciding with this has been the aging of forests throughout North America beyond their natural historic ranges, and the increase in community and industrial developments in forested areas which are creating a greater number of wildland/rural/industry interface boundaries. The latter has required unique fire management strategies. As the severity of the 2001 fire season developed in late May, Land and Forest Service escalated man-up and aircraft expenditures significantly above normal levels in expection of increased fire load (Figures 1-3). Prior to fire activity in the Protection Zone of Alberta, municipalities in the agricultural areas were experiencing extreme fire behaviour -

2021 Directory of Wildland Fire Management Personnel

2021 DIRECTORY OF WILDLAND FIRE MANAGEMENT PERSONNEL April 1, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Forest Fire Centres ....................................................................................................................................... i Provincial / Territorial Warehouses ............................................................................................................ ii Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (CIFFC) .................................................................................... 1 CIFFC Working Groups / Communities of Practice ................................................................................... 1 Forest Fire Management Agencies British Columbia ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Yukon ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Alberta ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Northwest Territories................................................................................................................................. 5 Saskatchewan .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Manitoba .................................................................................................................................................. -

Recent Impacts of Drought on Aspen and White Spruce Forests in Western Canada

Recent impacts of drought on aspen and white spruce forests in western Canada E.H. (Ted) Hogg and Michael Michaelian Canadian Forest Service, Northern Forestry Centre, 5320-122 Street, Edmonton, Alberta E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 110th CIF-IFC Conference and AGM Grande Prairie, Edmonton, September 19, 2018 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Natural Resources, 2017 1 Team members, collaborators & acknowledgments CIPHA research team Field & laboratory assistance Jim Hammond Ray Fidler Pam Melnick Ted Hogg (NoFC) Rick Hurdle Michelle Filiatrault Ryan Raypold Mike Michaelian (NoFC) Al Keizer Cathryn Hale Erin Van Overloop Trisha Hook (NoFC) Brad Tomm Bonny Hood Martin Robillard Mike Undershultz (Alberta AF) Jim Weber Tom Hutchinson Dan Rowlinson and others Devon Belanger Crystal Ionson Mark Schweitzer Marc Berube Amy Irvine Dominic Senechal Collaborators Natacha Bissonnette Oksana Izio Jessica Snedden Sarah Breen Angela Johnson Joey Tanney Lindsay Bunn Devin Letourneau Ryan Tew Craig Allen (USGS) Laura Chittick Jen MacCormick Bill van Egteren Alan Barr (Environment Canada) Brian Christensen Chelsea Martin Bryan Vroom Pierre Bernier (LFC) Owen Cook Sarah Martin Cedar Welsh Andy Black (UBC) Andrea Durand Lindsay McCoubrey Caroline Whitehouse Scott Goetz (NAU-ABoVE) Fraser McKee Dave Wieder Ron Hall (NoFC) and many others Bob Kochtubajda (EC) Funding Werner Kurz (PFC) Canada Climate Change Action Fund Vic Lieffers (U of Alberta) Program of Energy Research and Development -

Suceava, Romania

IUFRO WP 7.03.10 Methodology of forest insect and disease survey in Central Europe “Recent Changes in Forest Insects and Pathogens Significance” Working Party Meeting 16‐20 September 2019 ‐ Suceava, Romania Meeting programme (overview) Monday, 16 September 2019 13:00 – 19:00 Arrival 17:00 – 19:00 Registration 19:30 Dinner Tuesday, 17 September 2019 07:30 – 08:30 Breakfast and registration 09:00 – 09:40 Conference welcome and opening 09:40 – 10:00 Phytosanitary situation of Suceava County forests 10:00 – 11:20 Meeting Session 1: Oral presentations (4 presentations) (hotel conf. hall) 11:20 – 11:40 Coffee break 11:40 – 13:00 Meeting Session 2: Oral presentations (4 presentations) (hotel conf. hall) 13:00 – 14:00 Lunch break 14:00 – 15:40 Meeting Session 3: Oral presentations (5 presentations) (hotel conf. hall) 15:40 – 16:00 Going to ”Ștefan cel Mare” University 16:00 – 17:30 Poster session (coffee break included) (University E Building hall) 17:30 – 19:30 Free time (optional short Suceava City tour) 19:30 Dinner 1 Recent Changes in Forest Insects and Pathogens Significance Meeting of IUFRO WP 7.03.10 Methodology of forest insect and disease survey in Central Europe Wednesday, 18 September 2019 07:30 – 08:30 Breakfast 08:30 Field trip Thursday, 19 September 2019 07:30 – 08:30 Breakfast 09:00 – 10:40 Meeting Session 4: Oral presentations (5 presentations) (hotel conf. hall) 10:40 – 11:00 Coffee break 11:00 – 12:40 Meeting Session 5: Oral presentations (5 presentations) (hotel conf. hall) 12:40 – 14:00 Lunch break 14:00 – 15:40 Meeting Session 6: Oral presentations (5 presentations) (hotel conf. -

World Forestry Congress Paper

WORLD FORESTRY CONGRESS PAPER First Nations Forestry Program: An innovative integrated community development partnership approach By Alain Dubois1, Nello Cataldo2 and Reginald Parsons3 1. Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, 1055 du P.E.P.S., P.O. Box 3800, Sainte- Foy, QC, Canada G1V 4C7, Tel.: (418) 648-7134, Fax: (418) 648-2529, E-Mail: [email protected] 2. Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, 506 West Burnside Road, Room 239, Victoria, BC, Canada, V8Z 1M5, Tel.: (250) 363-6014, Fax: (25) 363-0775, E-Mail: [email protected] 3. Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, 580 Booth Street, 7th Floor, Ottawa, ON, Canada, K1A 0E4, Tel.: (613) 943-5230, Fax: (613) 947-7399, E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract Canada is home to over 600 First Nation bands from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans. From time immemorial, forests have been a way of life for First Nations, bringing together cultural, spiritual and social values. They have relied on forests for food, medicine, clothing and shelter. Forests continue to form an essential part of First Nations’ well-being, providing economic benefits and fulfilling cultural and spiritual needs for present and future generations. In 1996, the Government of Canada established the First Nations Forestry Program (FNFP) to help improve economic conditions in First Nation communities. Through this program, First Nations are able to build capacity and assume control of the management of forest resources on reserve lands, establish partnerships, and actively participate in off-reserve forestry and other economic development opportunities. First Nations are directly involved in the management of this innovative and highly successful program. -

Illegal Logging: a Market-Based Analysis of Trafficking in Illegal Timber

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Illegal Logging: A Market-Based Analysis of Trafficking in Illegal Timber Author(s): William M. Rhodes, Ph.D. ; Elizabeth P. Allen ; Myfanwy Callahan Document No.: 215344 Date Received: August 2006 Award Number: ASP TR-002 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Illegal Logging: A Market-Based Analysis of Trafficking in Illegal Timber Contract # 2004 TO 164 FINAL REPORT May 31, 2006 Prepared for Jennifer L. Hanley International Center National Institute of Justice 810 Seventh Street NW Washington, D.C. 20431 Prepared by William M. Rhodes, Ph.D. Elizabeth P. Allen, B.A. Myfanwy Callahan, M.S. Abt Associates Inc. 55 Wheeler Street Cambridge, MA 02138 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. -

The Canadian Forest Service Celebrated Its Centennial

In 1999, the Canadian Forest Service celebrated its centennial. The organization’s durability through a roller coaster of organizational focus and financial support is its legacy. For more than 100 years, its forward-looking solutions to forest management challenges have left a lasting imprint on the Canadian forest. Canada’s forests represent about 10 percent of the forests worldwide and with that responsibility the CFS is taking a leadership role on the international stage. The Canadian Forest Service: CATALYST FOR THE FOREST SECTOR anada is defined by its forests. They are the country’s dominant geograph- ical feature. They are also of central importance in the lives of Canadians, Cwhose attitudes toward their forests have changed over time. A little more than a century ago, an entirely new way of thinking about forests and the uses to which they could be put, evolved. The idea of the per- CFS’s expertise at providing a sound, scientific foundation for the petual forest emerged, a forest maintained forever by human evolving economic and social policies that determine the fate of effort, employing scientific management practices. Canada’s forests. Since then, there has been a steady evolution of that concept. Today, as we enter a new phase of the human relationship with THE CANADIAN FOREST: LIQUIDATION TO CONSERVATION forests, the scientific foundations of forest management, in com- bination with new social objectives, are more important than The mythical Canadian forest—an eternal pristine wilderness ever. Throughout this period, a single, small agency, now known unaltered by human intervention—has never existed. Until about as the Canadian Forest Service, led development of scientific for- 10,000 years ago, for several hundred centuries, virtually all of est management in Canada. -

NAFC Fact Sheet

N O R T H A M ER ican F O R E S T C ommi SS ion ( N A F C ) Atmospheric Change and Forests Working Group The Working Group on Atmospheric Change and Forests was established in 1984 when acid rain was a major global issue. The focus in the early years was on “atmospheric deposition.” In 1986, the group was also asked to consider broader climate change issues. As a result, most of the current working group members are scientists whose interests and expertise have evolved over the years to include the broader aspects of climate change. Current Activities/Impacts Recently, the Atmospheric Change and Forests Working Group has focused efforts on exchanging technologies and approaches used in the three countries to study, assess and forecast the impact of atmospheric changes on forests. Particular areas of assessing impact include species distribution and environmental niche change, process changes (such as Mission carbon cycling) as well as the effects of forest fire. The Atmospheric Change and Forests Working Group promotes In support of its objectives, the Atmospheric Change and the knowledge of forest ecosystems through science and Forests WG has jointly initiated a manuscript for submission monitoring of the effects of atmospheric changes on forests, to a peer reviewed journal. This manuscript aims to address and through cooperation and dissemination of new technologies the rationale for trilateral collaboration on the impacts of and techniques. atmospheric changes in North American forests. Objectives • Promote the collection, exchange and dissemination of information and techniques in the field of monitoring of forest health and the evaluation of the effects of atmospheric changes on forests. -

A Best Practices Guide for Generating Forest Inventory Attributes from Airborne Laser Scanning Data Using an Area-Based Approach

CANADIAN FOREST SERVICE CANADIAN WOOD FIBRE CENTRE INFORMATION REPORT FI-X-010 A best practices guide for generating forest inventory attributes from airborne laser scanning data using an area-based approach Joanne C. White, Michael A. Wulder, Andrés Varhola, Mikko Vastaranta, Nicholas C. Coops, Bruce D. Cook, Doug Pitt, and Murray Woods cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/publications The Canadian Wood Fibre Centre, Victoria, British Columbia The Canadian Wood Fibre Centre brings together forest sector researchers to develop solutions for the Canadian forest sector’s wood fibre related industries in an environmentally responsible manner. Its mission is to create innovative knowledge to expand the economic opportunities for the forest sector to benefit from Canadian wood fibre. The Canadian Wood Fibre Centre operates within the CFS, but under the umbrella of FPInnovations’ Board of Directors. FPInnovations is the world’s largest private, not-for-profit forest research institute. With over 600 employees spread across Canada, FPInnovations unites the individual strengths of each of these internationally recognized forest research and development institutes into a single, greater force. For more information visit http://www.FPInnovations.ca Additional information on Natural Resources Canada, the Canadian Forest Service, and Canadian Wood Fibre Centre research and publications is also available online at: cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/regions/cwfc. To download or order additional copies of this publication, see our online bookstore at: cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/publications. A best practices guide for generating forest inventory attributes from airborne laser scanning data using an area-based approach (Version 2.0) Joanne C. White1, Michael A. Wulder1, Andrés Varhola2, Mikko Vastaranta1,3, Nicholas C. -

Proceedings RMRS-P-6

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Workshop Participants Workshop Participants IUFRO Workshop Participants, August 23-26, 1998 Quebec City, Quebec, Canada 62 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-6. 1998. IU FRO Workshop Participants, August 23-26, 1998 Quebec City, Quebec, Canada 62 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-6. 1998. Workshop Participants jospeh Anawati Denver P. Burns jean Cook Canadian Forest Service USDA Forest Service Forintek Canada Corp. Head Office Rocky Mountain Research Station 2665 East Mall 580 Booth Street, 7th floor 240 West Prospect Road Vancouver, BC Ottawa, ON Fort Collins, CO 80526 USA V6T 1 WS Canada K1 A OE4 Canada (970) 498-1126 (604) 222-5633 (613) 947-8996 director/[email protected] cook@van. fori ntek.ca j anawati @n rcan .gc.ca (Speaker) jack Coster Lou is Archambau It Errol T. Caldwell West Virginia University Service canadien des forets Canadian Forest Service Agricultural Sciences Centre de foresterie des Laurentides Great Lakes Forestry Centre 1164 Agricultural Sciences 1055, rue du P.E.P.S. 1 21 9 Queen Street East Morgantown, WV 26506 USA Ste-Foy, Qc Sault Ste. Marie, ON (304) 293-4421 G 1V 4C7 Canada P6A 5M7 Canada [email protected] (418) 648-7230 (705) 759-5740-2037 larchambau [email protected]. forestry.ca [email protected] Dave Cown (Group facilitator) Forest Research Institute janice Campbell PO Box 3020 Philip Aune Canadian Forest Service Rotorua, New Zealand USDA Forest Service Atlantic Forest Centre 64 7 347 5525 Pacific Southwest Research Station P.O. -

Cdn Forest History Preservation Project

The Canadian Forest History Preservation Project / Projet canadien de conservation d!histoire de forêt being a collaboration between the Canadian Forest Service, the Forest History Society, and the Network in Canadian History and Environment. Prepared by David Brownstein of Klahanie Research Ltd. for Ken Farr (Canadian Forest Service), Steven Anderson (FHS) and Alan MacEachern & Graeme Wynn (NiCHE). October 31, 2012 Objective “The purpose of the project was to research, discover and compile an inventory of significant caches of existing records of Canadian Forest History. Although the inventory will not be complete by the Project end date, a process will be started which will identify suitable repositories.” Scope Deliverables produced during the contract include a national survey of repositories; an inventory of repositories able and willing to accept donation of forest history collections; a search for records in danger of loss or destruction; facilitation of those records into the appropriate archive; and English and French versions of a project brochure. 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Synopsis of Recommendations 3 Summary of Context 4 Brochure and Communications 5 Facilitation of Archival Donations 6 The Archival Survey 11 Survey Analysis Distribution of Institution Types Archivists Climate Control Forest History Collections Mandate to Increase Forest History Collections Willingness to expand forest history collections Obstacles to increasing forest history collections Adequate money and staff resources Hidden Collections