'Graffiti' and 'Street Art'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere Something Possible

NYC 1983–84 NYC PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere Something Possible PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere NYC 1983–84 PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere NYC 1983–84 Jane Bauman PIER 34 Mike Bidlo Something Possible Everywhere Paolo Buggiani NYC 1983–84 Keith Davis Steve Doughton John Fekner David Finn Jean Foos Luis Frangella Valeriy Gerlovin Judy Glantzman Peter Hujar Alain Jacquet Kim Jones Rob Jones Stephen Lack September 30–November 20 Marisela La Grave Opening reception: September 29, 7–9pm Liz-N-Val Curated by Jonathan Weinberg Bill Mutter Featuring photographs by Andreas Sterzing Michael Ottersen Organized by the Hunter College Art Galleries Rick Prol Dirk Rowntree Russell Sharon Kiki Smith Huck Snyder 205 Hudson Street Andreas Sterzing New York, New York Betty Tompkins Hours: Wednesday–Sunday, 1–6pm Peter White David Wojnarowicz Teres Wylder Rhonda Zwillinger Andreas Sterzing, Pier 34 & Pier 32, View from Hudson River, 1983 FOREWORD This exhibition catalogue celebrates the moment, thirty-three This exhibition would not have been made possible without years ago, when a group of artists trespassed on a city-owned the generous support provided by Carol and Arthur Goldberg, Joan building on Pier 34 and turned it into an illicit museum and and Charles Lazarus, Dorothy Lichtenstein, and an anonymous incubator for new art. It is particularly fitting that the 205 donor. Furthermore, we could not have realized the show without Hudson Gallery hosts this show given its proximity to where the the collaboration of its many generous lenders: Allan Bealy and terminal building once stood, just four blocks from 205 Hudson Sheila Keenan of Benzene Magazine; Hal Bromm Gallery and Hal Street. -

Recognized Stature: Protecting Street Art As Cultural Property

Chicago-Kent Journal of Intellectual Property Volume 12 Issue 2 Article 2 7-1-2013 Recognized Stature: Protecting Street Art as Cultural Property Griffin M. Barnett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/ckjip Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Griffin M. Barnett, Recognized Stature: Protecting Street Art as Cultural Property, 12 Chi. -Kent J. Intell. Prop. 204 (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/ckjip/vol12/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Journal of Intellectual Property by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RECOGNIZED STATURE: PROTECTING STREET ART AS CULTURAL PROPERTY Griffin M. Barnett INTRODUCTION I was very embarrassed when my canvases began to fetch high prices, I saw myself condemned to a future of painting nothing but masterpieces. —Henri Matisse1 Copyright © 2013, Griffin Barnett; Chicago-Kent College of Law. Associate, Silverberg, Goldman & Bikoff, LLP, Washington, DC. The author holds a JD, cum laude, from American University Washington College of Law and a BA in International Studies from Johns Hopkins University. The author would like to thank his family and friends for their unwavering love and support, and Professor Joshua J. Kaufman for providing the impetus for writing this Article. ** Photograph provided by Fine Art Auctions Miami. 1 Frequently asked questions, BANKSY, http://web.archive.org/web/2013062716574 1/http://www.banksy.co.uk/QA/qaa.html (accessed by searching http://www.banksy.co. -

Graffiti and Street Art Free

FREE GRAFFITI AND STREET ART PDF Anna Waclawek | 208 pages | 30 Dec 2011 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500204078 | English | London, United Kingdom Graffiti vs. Street Art Make The GraffitiStreet newsletter your first port of call, and leave the rest to us. As well as showcasing works from established artists we will be continuously scouring the globe to discover and bring you the freshest upcoming artist talent. Around the clock, GraffitiStreet's dedicated team of art lovers are here to bring you the best and latest street art in the world! So, what are you waiting for? Explore the world of street art! The son of Entitled after the quality of Graffiti and Street Art strong, much needed in the A new mural by the elusive Banksy has been painted on Graffiti and Street Art side of a hair and beauty salon on the corner of Rothesay Avenue in Nottingham. The image depicts a girl playing with a disused Amadora celebrates itself as a multicultural city that celebrates diversity as Want to keep up with the latest street art news and views? Email address There's no Spam, and we'll never sell on your details. That's a promise! Looking for an authentic Banksy artwork? Full pest control certificate and condition report Browse The Collection. Hand pulled screen prints, Hand finished prints, Etchings and more! Bringing you our own limited edition prints Browse Our Editions. Check out Graffiti and Street Art online store for secondary market artworks Browse The Collection. Murals, Festivals, Interviews and more Bringing you the latest street art news from all over the Graffiti and Street Art Read more. -

Lorraine O'grady Writing in Space

Mlle Bourgeoise Noire and her Master of Ceremonies arrive for her 25th Anniversary celebration at precisely 9:00 p.m. They have dificulty entering (their names having been omitted from the guest list at the door). After a few peremptory commands by Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, they are let in, passing through the tight pink maze especially designed by artist David Hammons and featuring three salt ish hanging from hooks. At last they can greet the crowds awaiting them. Oohs and aahs on all sides for Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s gown. After all these years, it still its. She smiles, she smiles, she smiles. Mlle Bourgeoise Noire has lost none of the charm that originally won her crown. Each of her nine tails has three white chrysanthemums, which she gives to her subjects one at a time as she says, while smiling brightly, “Won’t you help me lighten my heavy bouquet?” She moves gradually around the room. Photographers and video cameramen are having a ield day. Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, in her 180 pairs of white gloves, white cat-o- nine-tails, and rhinestone and seed pearl crown, is very photogenic. Unreluctantly, she obliges them. But Mlle Bourgeoise Noire has had a change of heart between 1955 and 1980. She has come to a conclusion. As the band goes on its break, she discreetly retires. All her flowers have been given away, and now she removes her cape, handing it to her Master of Ceremonies. She is wearing a backless, white-glove gown. Her , by prearranged signal, hands her a pair of above-the-elbow gloves, which she proceeds to put on. -

Revisiting the Detective Show 63 64 65 66 Xxx 67 68 69 70 71 72 Revisiting the Detective Show 73 74 75 76 77 78 Revisiting the Detective Show 79

62 NUART JOURNAL 2021 VOLUME 3 NUMBER 1 62–79 Revisiting The Detective Show Gorman Park Queens NYC John Fekner May 7–June 30, 1978 The Detective Show was quite unlike current (or at least, pre- Created for an unsuspecting Queens neighbourhood com- pandemic) street art festivals, with their spectacular large munity, it was unexpected and not intended to overwhelm murals, bright colours, and street fair atmosphere. The the viewer. It was beyond the visible; a kind of hide and show was quiet and removed; distanced from the usual seek art game; participatory projects that made you engage New York art world locations and audiences. Extremely with the work which ultimately would inform, question and low key; it was a temporary art installation about subtlety, challenge the concept of art, with viewers of all ages, nuance, and the magic of discovery by happenstance. within a New York City playground. REVISITING THE DETECTIVE SHOW 63 64 65 66 XXX 67 68 69 70 71 72 REVISITING THE DETECTIVE SHOW 73 74 75 76 77 78 REVISITING THE DETECTIVE SHOW 79 All photographs courtesy of ©John Fekner John Fekner is a multimedia artist best known for his series and ©Len Bellinger archives. Queens, New York. of environmentally conceptual works consisting of words, symbols, and dates painted throughout the five boroughs of New York in 'Memory' was not part of the 'Detective Show', 1981. the '70s. The ‘Warning Signs’ pointed out hazards and dangerous Photograph: ©Martha Cooper conditions that overtook a financially bankrupt city in disrepair. Using hand-cut cardboard stencils and spray paint, he began in In order of appearance: the industrial streets of Queens and on the East River bridges, Richard Artschwager (black blps on parkhouse) and continuing to the South Bronx in 1980 where his ‘messages’ Carolyn Conrad (handball court installation in progress) brought awareness to areas that were in desperate need of Elisa D'Arrigo (fence installation in progress) attention, whether through demolition or repairs. -

La Creatividad Como Forma De Identidad Y Ejercicio De Ciudadanía

LA CREATIVIDAD COMO FORMA DE IDENTIDAD Y EJERCICIO DE CIUDADANÍA. El caso del postgraffiti. Dr. Jesús Alberto Peredo Pozos 46 Arq. Melissa Guadalupe Retamoza Ávila 47 PALABRAS CLAVE: Postgraffiti, identidad, creatividad, ciudadanía. Resumen Dentro de los diversos fenómenos socio-urbanos contemporáneos, los que corresponden a la contracultura son algunos de los que tienen mayor impacto y participación específica en la esfera pública. Estas formas de cohabitar un territorio supone, en la mayoría de los casos un rechazo sistemático generalizado, tanto por la irrupción al orden establecido, como por su condición emergente y sus lenguajes novedosos, codificados y transgresores con que se manifiestan. A pesar de que los sectores sociales oficialmente válidos no reconocen de una forma abierta su autenticidad e importancia para el autoconocimiento social y territorial, la permanencia de estas formas subversivas de habitar la ciudad, habla de una fuerza que construye tanto identidades como patrimonio e imaginarios al paso del tiempo. Ejemplo de lo anterior, podría ser el fenómeno graffiti surgido en los años 70 del pasado siglo, que luego de haber sido objeto de persecución policiaca, al paso de los años algunas de éstas obras han llegado a otorgar una suerte de identidad comunitaria o patrimonio urbano insospechado. Este sería el caso de las intervenciones del denominado “padre del graffiti” Taki 183, a quien en la actualidad le dedican homenajes, retrospectivas, exposiciones y hasta la protección o conservación de las pocas intervenciones que aún persisten dentro del Area Metropolitana de Nueva York. Años después se han replicado fenómenos alrededor del mundo como el caso del artista inglés Banksy, que ha llegado a conmocionar tanto a las autoridades como a corredores de arte y ciudadanos de todo el mundo. -

Woodward Gallery Established 1994

Woodward Gallery Established 1994 Richard Hambleton 1954 Born Vancouver, Canada. 1975 BFA, Painting and Art History at the Emily Carr School of Art, Vancouver, BC 1975-80 Founder and Co-Director “Pumps” Center for Alternative Art, Gallery, Performance and Video Space; Vancouver, BC; The Furies: Western Canada’s first punk band played their first gig at Richard Hambleton’s Solo Exhibition, May, 1976. Lives and works in New York City’s Lower East Side. SOLO EXHIBITION S 2013 “Beautiful Paintings,” Art Gallery at the Rockefeller State Park Preserve, Sleepy Hollow, NY 2011 “Richard Hambleton: A Retrospective,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with Phillips de Pury and Giorgio Armani at Phillips de Pury & Company, New York 2010 “Richard Hambleton New York, The Godfather of Street Art,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with Giorgio Armani at The Dairy, London “Richard Hambleton New York,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with Giorgio Armani at the State Museum of Modern Art of the Russian Academy of Arts, Moscow “Richard Hambleton New York,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with Giorgio Armani, Milan “Richard Hambleton New York,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with Giorgio Armani, amFAR Annual Benefit, May 20, 2010 2009 “Richard Hambleton New York,” presented by Andy Valmorbida and Vladimir Restoin Roitfeld in collaboration with -

Is Street Art a Crime? an Attempt at Examining Street Art Using Criminology

Advances in Applied Sociology 2012. Vol.2, No.1, 53-58 Published Online March 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2012.21007 Is Street Art a Crime? An Attempt at Examining Street Art Using Criminology Zeynep Alpaslan Department of Sociology, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey Email: [email protected] Received February 1st, 2012; revised February 29th, 2012; accepted March 13th, 2012 A clear and basic definition is the fundamental element in understanding, thus explaining any social sci- entific concept. Street art is a social phenomenon, characterized by its illegal nature, which social scien- tists from several subjects have increasingly been examining, interpreting and discussing for the past 50 years. Even though the concept itself has been defined much more clearly over the years, its standing concerning whether it is a crime or form of art is still a borderline issue. This paper attempts to first try to define street art under a type of crime, then examine it using criminological perspective, with crimino- logical and deviance theories in order to understand and explain it better using an example, the KÜF Pro- ject from Ankara Turkey. Keywords: Street Art; Definition; Criminology; Crime Theory; KÜF Project Introduction what it has to offer. The street artists, who use the technologies of the modern time to claim space, communicate ideas, and Art, in the general sense, is the process and/or product of de- express social and/or political views, have motivations and liberately arranging elements in a way that appeals to the senses objectives as varied as the artists themselves. -

Stencilling-Anushka

Questions How did stencilling begin ? When was it first seen as an art form in the streets? Who are the artists currently employing it ? What is Stencilling? Stencil graffiti makes use of stencils made out of paper, cardboard, or other media to create an image or text that is easily reproducible. The desired design is cut out of the selected medium and then the image is transferred to a surface through the use of spray paint or roll- on paint. Often the stencils express political and social opinions of the artist, or are simply images of pop culture icons. By Golan Levin, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania How did stencilling begin? When was it first seen as an art form in the streets? Those who began stencilling may have had many motivations. It is a cheap and easy method to produce a message. Because stencils are prepared ahead of time, and spraying (or rolling) over them is quite quick, a street artist can make a detailed piece in seconds. Since the stencil stays uniform throughout its use, it is easier for an artist to quickly replicate what could be a complicated piece at a very quick rate. The stencil graffiti subculture has been around since the mid 60s to 70s and evolved from the freestyle graffiti seen in the New York City subways and streets. Social turmoil ruled the United States in the 1970s, which gave rise to anti-establishment movements. Punk rock bands, such as Black Flag and Crass, and punk venues would stencil their names and logos across cities and became known as symbols to the punk scene. -

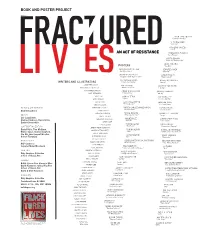

Book and Poster Project an Act of Resistance

BOOK AND POSTER PROJECT IGOR LANGSHTEYN “Secret Formulas” SEYOUNG PARK “Hard Hat” CAROLINA CAICEDO “Shell” AN ACT OF RESISTANCE FRANCESCA TODISCO “Up in Flames” CURTIS BROWN “Not in my Fracking City” WOW JUN CHOI POSTERS “Cracking” SAM VAN DEN TILLAAR JENNIFER CHEN “Fracktured Lives” “Dripping” ANDREW CASTRUCCI LINA FORSETH “Diagram: Rude Algae of Time” “Water Faucet” ALEXANDRA ROJAS NICHOLAS PRINCIPE WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS “Protect Your Mother” “Money” SARAH FERGUSON HYE OK ROW ANDREW CASTRUCCI ANN-SARGENT WOOSTER “Water Life Blood” “F-Bomb” KATHARINE DAWSON ANDREW CASTRUCCI MICHAEL HAFFELY MIKE BERNHARD “Empire State” “Liberty” YOKO ONO CAMILO TENSI JUN YOUNG LEE SEAN LENNON “Pipes” “No Fracking Way” AKIRA OHISO IGOR LANGSHTEYN MORGAN SOBEL “7 Deadly Sins” CRAIG STEVENS “Scull and Bones” EDITOR & ART DIRECTOR MARIANNE SOISALO KAREN CANALES MALDONADO JAYPON CHUNG “Bottled Water” Andrew Castrucci TONY PINOTTI “Life Fracktured” CARLO MCCORMICK MARIO NEGRINI GABRIELLE LARRORY DESIGN “This Land is Ours” “Drops” CAROL FRENCH Igor Langshteyn, TERESA WINCHESTER ANDREW LEE CHRISTOPHER FOXX Andrew Castrucci, Daniel Velle, “Drill Bit” “The Thinker” Daniel Giovanniello GERRI KANE TOM MCGLYNN TOM MCGLYNN KHI JOHNSON CONTRIBUTING EDITORS “Red Earth” “Government Warning” JEREMY WEIR ALDERSON Daniel Velle, Tom McGlynn, SANDRA STEINGRABER TOM MCGLYNN DANIEL GIOVANNIELLO Walter Sipser, Dennis Crawford, “Mob” “Make Sure to Put One On” ANTON VAN DALEN Jim Wu, Ann-Sargent Wooster, SOFIA NEGRINI ALEXANDRA ROJAS DAVID SANDLIN Robert Flemming “No” “Frackicide” -

California State University, Northridge Shepard Fairey

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE SHEPARD FAIREY AND STREET ART AS POLITICAL PROPAGANDA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Art, Art History by Andrea Newell August 2016 Copyright by Andrea Newell 2016 ii The thesis of Andrea Newell is approved: _______________________________________________ ____________ Meiqin Wang, Ph.D. Date _______________________________________________ ____________ Owen Doonan, Ph.D. Date _______________________________________________ ____________ Mario Ontiveros, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Mario Ontiveros of the Art Department at California State University, Northridge. He always challenged me in a way that brought out my best work. Our countless conversations pushed me to develop a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of my research and writing as well as my knowledge of theory, art practices and the complexities of the art world. He consistently allowed this paper to be my own work, but guided me whenever he thought I needed it, my sincerest thanks. My deepest gratitude also goes out to my committee, Dr. Meiqin Wang and Dr. Owen Doonan, whose thoughtful comments, kind words, and assurances helped this research project come to fruition. Without their passionate participation and input, this thesis could not have been successfully completed. I would also like to acknowledge Dr. Peri Klemm for her constant support beyond this thesis and her eagerness to provide growth opportunities in my career as an art historian and educator. I am gratefully indebted to my co-worker Jessica O’Dowd for our numerous conversations and her input as both a friend and colleague. -

Banksy. Urban Art in a Material World

Ulrich Blanché BANKSY Ulrich Blanché Banksy Urban Art in a Material World Translated from German by Rebekah Jonas and Ulrich Blanché Tectum Ulrich Blanché Banksy. Urban Art in a Material World Translated by Rebekah Jonas and Ulrich Blanché Proofread by Rebekah Jonas Tectum Verlag Marburg, 2016 ISBN 978-3-8288-6357-6 (Dieser Titel ist zugleich als gedrucktes Buch unter der ISBN 978-3-8288-3541-2 im Tectum Verlag erschienen.) Umschlagabbildung: Food Art made in 2008 by Prudence Emma Staite. Reprinted by kind permission of Nestlé and Prudence Emma Staite. Besuchen Sie uns im Internet www.tectum-verlag.de www.facebook.com/tectum.verlag Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Angaben sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Table of Content 1) Introduction 11 a) How Does Banksy Depict Consumerism? 11 b) How is the Term Consumer Culture Used in this Study? 15 c) Sources 17 2) Terms and Definitions 19 a) Consumerism and Consumption 19 i) The Term Consumption 19 ii) The Concept of Consumerism 20 b) Cultural Critique, Critique of Authority and Environmental Criticism 23 c) Consumer Society 23 i) Narrowing Down »Consumer Society« 24 ii) Emergence of Consumer Societies 25 d) Consumption and Religion 28 e) Consumption in Art History 31 i) Marcel Duchamp 32 ii) Andy Warhol 35 iii) Jeff Koons 39 f) Graffiti, Street Art, and Urban Art 43 i) Graffiti 43 ii) The Term Street Art 44 iii) Definition