126613916.23.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall IV7

Achbeag, Cullicudden, Balblair, Dingwall Achbeag, Outside The property is approached over a tarmacadam Cullicudden, Balblair, driveway providing parking for multiple vehicles Dingwall IV7 8LL and giving access to the integral double garage. Surrounding the property, the garden is laid A detached, flexible family home in a mainly to level lawn bordered by mature shrubs popular Black Isle village with fabulous and trees and features a garden pond, with a wide range of specimen planting, a wraparound views over Cromarty Firth and Ben gravelled terrace, patio area and raised decked Wyvis terrace, all ideal for entertaining and al fresco dining, the whole enjoying far-reaching views Culbokie 5 miles, A9 5 miles, Dingwall 10.5 miles, over surrounding countryside. Inverness 17 miles, Inverness Airport 24 miles Location Storm porch | Reception hall | Drawing room Cullicudden is situated on the Black Isle at Sitting/dining room | Office | Kitchen/breakfast the edge of the Cromarty Firth and offers room with utility area | Cloakroom | Principal spectacular views across the firth with its bedroom with en suite shower room | Additional numerous sightings of seals and dolphins to bedroom with en suite bathroom | 3 Further Ben Wyvis which dominates the skyline. The bedrooms | Family shower room | Viewing nearby village of Culbokie has a bar, restaurant, terrace | Double garage | EPC Rating E post office and grocery store. The Black Isle has a number of well regarded restaurants providing local produce. Market shopping can The property be found in Dingwall while more extensive Achbeag provides over 2,200 sq. ft. of light- shopping and leisure facilities can be found in filled flexible accommodation arranged over the Highland Capital of Inverness, including two floors. -

Scottish Photographers NOTES Summer 2010

Scottish Photographers NOTES Summer 2010 Scottish Photographers is a network of independent photographers in Scotland. Scottish Photographers www.scottish-photographers.com Contents [email protected] 3 Editorial Organiser: Carl Radford 15 Pittenweem Path High Blantyre G72 OGZ 4 Andy Biggs: An English River 01698 826414 [email protected] 10 Stefan Serowatka: Northern Grace Editor: Sandy Sharp 33 Avon Street Motherwell ML1 3AA 16 John Kemplay: Shop Windows 01698 262 313 [email protected] 18 Spotlight: Colin Gray Accountant: Stewart Shaw 13 Mount Stuart Street Glasgow G41 3YL 20 Melanie Sims: Memorandum 0141 632 8926 [email protected] 24 At Work: The Photographic Work of Jakob Jakobsson Webmaster: Jamie McAteer 88/4 Craighouse Gardens Edinburgh EH 10 5LW 28 Donald Stewart. Book Review: Tillman Crane Jordan 0797 13792424 [email protected] 30 Michael Thomson: Wind Farms in Inner Mongolia NOTES for Scottish Photographers is published three times a year, in January, May and September. 34 Robin Gillanders on Diane Arbus If a renewal form is enclosed then your annual subscription is 36 The Photographers' Place due. Donations are always welcome. 37 News and Events Individuals £10.00; Concessions £5.00; Overseas £15.00. Front Cover Jakob Jakobsson: Surveyors NOTES for Scottish Photographers Number Twenty Summer 2010 Michael Shulman. This makes us wonder; when is a Scottish Pho- tographer ever going to apply to join Magnum? The last issue of NOTES had an elegaic theme and the work of Melanie Sims continues this. The Park Gallery in Falkirk was the venue for a truly beautiful exhibition which showed work that Mela- nie had been gradually introducing to the Street Level meetings. -

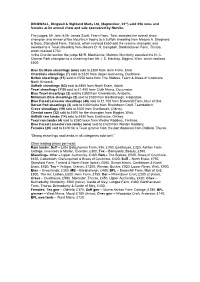

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts Ltd, (September, 23rd) sold 358 rams and females at its annual show and sale sponsored by Norvite. The judges, Mr John & Mr James Scott, Fearn Farm, Tain, awarded the overall show champion and winner of the Mountrich trophy to a Suffolk shearling from Messrs A. Shepherd & Sons, Stonyford Farm, Tarland, which realised £650 and the reserve champion was awarded to a Texel shearling from Messrs D. N. Campbell, Bardnaclaven Farm, Thurso, which realised £700. In the Cheviot section the judge Mr R. MacKenzie, Muirton, Munlochy awarded the N. C. Cheviot Park champion to a shearling from Mr J. S. MacKay, Biggins, Wick, which realised £600. Blue Du Main shearlings (one) sold to £500 from Hern Farm, Errol. Charollais shearlings (7) sold to £320 from Upper Auchenlay, Dunblane. Beltex shearlings (15) sold to £550 twice from The Stables, Fearn & Braes of Coulmore, North Kessock. Suffolk shearlings (63) sold to £850 from North Essie, Adziel. Texel shearlings (119) sold to £1,450 from Clyth Mains, Occumster. Blue Texel shearlings (2) sold to £380 from Greenlands, Arabella. Millenium Blue shearlings (2) sold to £500 from Bardnaheigh, Harpsdale. Blue Faced Leicester shearlings (46) sold to £1,100 from Broomhill Farm, Muir of Ord. Dorset Poll shearlings (4) sold to £300 twice from Rheindown Croft, Teandalloch. Cross shearlings (19) sold to £600 from Overhouse, Orkney. Cheviot rams (32) sold to £600 for the champion from Biggins, Wick. Suffolk ram lambs (14) sold to £420 from Easthouse, Orkney. Texel ram lambs (4) sold to £380 twice from Wester Raddery, Fortrose. Blue Faced Leicester ram lambs (one) sold to £420 from Wester Raddery. -

Scottish Language Letter Cle To

CLE [449] CLE 1 radically the same. From the form of the A.-S. word, Nor his bra targe, on which is seen it seems to have been common to the Celtic and The ycr.l, the sin, the lift, the Can well agree wi' his cair Gothic ; and probably dough had originally aamc cleuck, That cleikit was for thift. sense with Ir. rloiclte, of, or belonging to, a rock or Poems in the Buchan 12. stone. V. CLOWK. Dialect, p. This term is transferred Satchels, when giving the origin of the title Sue- to the hands from their i-li or hold of E. of niih, supplies us with a proof of clench and heuclt being griping laying objects. clutch, which neither Skinner nor Johnson is synon. : gives any etymon, evidently from the same Junius derives clutches Ami for the buck thou stoutly brought origin. from to shake ; but without reason. To us up that steep heugh, Belg. klut-en, any Thy designation ever shall Shaw gives Gael, glaic as signifying clutch. Somner Be John Scot in [ot\Buckscleugh. views the E. word as formed from A.-S. gecliht, "col- History Jfame of Scot, p. 37. lectus, gathered tegether : hand gecliht, manus collecta vel contracta," in modern language, a clinched fat. CLEUCII, adj. 1. Clever, dextrous, light- But perhaps cleuk is rather a dimin. from Su.-G. klo, fingered. One is said to have cleuch hands, Teut. klaawe, a claw or talon. Were there such a word as Teut. as from or to be "cleuch of the fingers," who lifts klugue, unguis, (mentioned GL the resemblance would be so that do not Kilian, Lyndsay, ) greater. -

(November 16Th) Sold 26 Goats, 4 Alpaca, 799 Sheep and 457 Lots of Poultry, Eggs & Poultry Equipment at Their, Rare & Traditional Breeds of Livestock Sale

DINGWALL, Dingwall & Highland Marts (November 16th) sold 26 goats, 4 alpaca, 799 sheep and 457 lots of poultry, eggs & poultry equipment at their, rare & traditional breeds of livestock sale. Goats (26) sold to £380 for pygmy female with a kidd at foot from Allt A’Bhonich, Stromeferry. Alpaca (4) sold to £550 gross for a pair of males from Meikle Geddes, Nairn. Sheep (799) sold to £1,600 gross for a Valais Blacknose ram from 9 Drumfearn, Isleornsay. Poultry (457) sold to £170 gross for a trio of Mandarin from old Schoolhouse, Balvraid. Sheep other leading prices: Zwartble gimmer: 128 Kinlochbervie, Kinlochbervie, £110. Zwartble in lamb gimmers: Carn Raineach, Applecross, £180. Zwartble ewe: 1 Georgetown Farm, Ballindalloch, £95. Zwartble in lamb ewe: Old School, North Strome, £95 Zwartble ewe lambs: Speylea, Fochabers, £85. Zwartble tup lamb: Old School, £55. Zwartble rams: Wester Raddery, £320. Sheep: Lambs: Valais Blacknose – Scroggie Farm, Dingwall, £500; Dorset – An Cala, Canisby, £200; Ryeland – Stronavaich, Tomintoul, £150; Blue Faced Leicester – Beldhu, Croy, £130; Herdwick – Broombank, Culloden, £110; Border Leicester – Balmenach Farm, Ballater, £105; Kerryhill – Invercharron Mains, Ardgay, £100 (twice); Jacob – Lochnell Home Farm, Benderloch, £100; Cheviot – Cuilaneilan, Kinlochewe & Bogburn Farm, Duncanston, £90; Texel – Inverbay, Lower Arboll, £90 (twice); Llanwenog – Burnfield Farm, Rothiemay, £80; Clune Forest – 232 Proncycroy, Dornoch, £74; Blackface – Bogburn Farm, £60; Gotland – Myre Farm, Dallas, £60; Hebridean – Broomhill Farm, Muir of Ord, £55; Shetland – Upper Third Croft, Rothienorman, £50.Gimmers: Beltex – Knockinnon, Dunbeath, £300; Cheviot – Cuilaneilan, £220; Herdwick – Duror, Glenelg, £170; Dorset – Knockinnon, £155; Ryeland – 5 Terryside, Lairg, £120; Jacob – Killin Farm, Garve, £85; Hebridean – Eagle Brae, Struy, £65; Shetland – Lamington, Oyne, £50; Texel – Sandside Cottage, Tomatin, £50. -

Maccoinnich, A. (2008) Where and How Was Gaelic Written in Late Medieval and Early Modern Scotland? Orthographic Practices and Cultural Identities

MacCoinnich, A. (2008) Where and how was Gaelic written in late medieval and early modern Scotland? Orthographic practices and cultural identities. Scottish Gaelic Studies, XXIV . pp. 309-356. ISSN 0080-8024 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/4940/ Deposited on: 13 February 2009 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk WHERE AND HOW WAS GAELIC WRITTEN IN LATE MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN SCOTLAND? ORTHOGRAPHIC PRACTICES AND CULTURAL IDENTITIES This article owes its origins less to the paper by Kathleen Hughes (1980) suggested by this title, than to the interpretation put forward by Professor Derick Thomson (1968: 68; 1994: 100) that the Scots- based orthography used by the scribe of the Book of the Dean of Lismore (c.1514–42) to write his Gaelic was anomalous or an aberration − a view challenged by Professor Donald Meek in his articles ‘Gàidhlig is Gaylick anns na Meadhon Aoisean’ and ‘The Scoto-Gaelic scribes of late medieval Perth-shire’ (Meek 1989a; 1989b). The orthography and script used in the Book of the Dean has been described as ‘Middle Scots’ and ‘secretary’ hand, in sharp contrast to traditional Classical Gaelic spelling and corra-litir (Meek 1989b: 390). Scholarly debate surrounding the nature and extent of traditional Gaelic scribal activity and literacy in Scotland in the late medieval and early modern period (roughly 1400–1700) has flourished in the interim. It is hoped that this article will provide further impetus to the discussion of the nature of the literacy and literary culture of Gaelic Scots by drawing on the work of these scholars, adding to the debate concerning the nature, extent and status of the literacy and literary activity of Gaelic Scots in Scotland during the period c.1400–1700, by considering the patterns of where people were writing Gaelic in Scotland, with an eye to the usage of Scots orthography to write such Gaelic. -

V. Notes on the Contents of Two Viking Graves in Islay

V. E CONTENT NOTEO TH VIKIN N TW O SF GO S GRAVE N ISLAYI S , DISCOVERED BY WILLIAM CAMPBELL, ESQ., OF BALLINABY; WITH NOTICES OF THE BURIAL CUSTOMS OF THE NORSE SEA- KINGS S RECORDEA ,E SAGA TH D ILLUSTRATE AN N SI D Y B D THEIR GRAVE-MOUNDS IN NORWAY AND IN SCOTLAND. Bv JOSEPH ANDERSON, ASSISTANT SEOKETAIIY, AND KEEPER OF THE MUSEUM. The contents of the two graves now to be described were discovered by William Campbell, Esq. Ballinabyf o , sande th n y,i link t Ballinabysa n ,i islane th Islayf do Augusn ,i t 1878 I heardiscovere . th f do Septembeyn i r through Dr Hunter; and recognising it from his description as a deposit of the heathen Viking time, I wrote to Mr Campbell requesting him to entrusr description— fo e articles th e t m o t ' a request with whice h courteously complie y bringinb d g the o Edinburgmt d ultimatelan h y presenting them to the Museum. Mr Campbell states that the discovery was made in consequence of the drifting of the sand showing a deposit of rust on the surface; and on digging to the depth of about 15 inches he found two skeletons a little apart with their heads towards the east. A line of stones on edge formed a sort of enclosure round each of the skeletons othee Th r. content f thso e graves wer follows ea s :— QRAVE No. I. 1. An iron sword in its sheath. 2. Iron bosshielda f so , wit handls hit e attached. -

STD Code Book for 1984 Based on Haddenham & Long Crendon Issue 4, 1984

STD Code Book for 1984 Based on Haddenham & Long Crendon Issue 4, 1984 01 London 0207 Burnopfield 0200 Clitheroe 0207 Consett 0200 5 Gisburn 0207 Dipton 0200 6 Slaidburn 0207 Ebchester 0200 7 Bolton-by-Bowland 0207 Edmundbyers 0200 8 Dunsop Bridge 0207 Lanchester (Co Durham) 0202 Bournemouth 0207 Rowlands Gill 0202 Broadstone 0207 Stanley (Co Durham) 0202 Canford Cliffs 0208 Bodmin 0202 Christchurch (Dorset) 0208 Lanivet 0202 Ferndown 0208 81 Wadebridge 0202 Lytchett Minster 0208 82 Cardinham 0202 Parkstone 0208 84 St Mabyn 0202 Poole 0208 86 Trebetherick 0202 Verwood 0208 88 Port Isaac 0202 Wimborne (Dorset) 0209 Camborne 0203 Bedworth 0209 Porthtowan 0203 Chapel End 0209 Portreath 0203 Coventry 0209 Praze 0203 Nuneaton 0209 Redruth 0203 Royal Show 0209 St Day 0203 Wolston 0209 Stithians 0203 33 Keresley (Coventry) 021 Birmingham 0204 Bolton 0220 23 Histon 0204 Farnworth 0220 26 Comberton 0204 Horwich (Lancs) 0220 29 West Wratting 0204 Turton 0220 5 Teversham 0204 81 Belmont Village 0221 22 Limpley Stoke 0204 88 Tottington 0221 4 Trowbridge (4 & 5 fig nos) 0205 Boston (Lincs) 0221 6 Bradford-on-Avon 0205 73 Langrick 0221 7 Saltford (4 fig nos) 0205 78 Stickney 0222 Caerphilly 0205 79 Hubbert's Bridge 0222 Cardiff 0205 84 New Leake 0222 Dinas Powys 0205 85 Fosdyke 0222 Penarth 0205 86 Sutterton 0222 Pentyrch 0206 Colchester 0222 Radyr (Sth Glam) 0206 Great Bentley 0222 Senghenydd 0206 Nayland (Colchester) 0222 Sully 0206 West Mersea 0222 Taffs Well 0206 22 Wivenhoe 0223 Cambridge 0206 28 Rowhedge 0224 Aberdeen 0206 30 Brightlingsea 0224 -

The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation

. JVASV^iX ^ N^ {/) lSNrNVIN0SHilWS*^S3ldVaan^LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Ni <n - M ^^ <n 5 CO Z ^ ^ 2 ^—^ _j 2 -I RIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHilWS S3iyVdan U r- ^ ^ 2 CD 4 A'^iitfwN r: > — w ? _ ISNI NVINOSHilWS SBiyVdan LIBRARIES'SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION f^ <rt .... CO 2 2 2 s;- W to 2 C/J • 2 CO *^ 2 RIES SMITHSONIAN_INSTITUTlON NOIiniliSNI_NVINOSHilWS S3liiVyan_L; iiSNi"^NViNOSHiiNS S3iyvaan libraries smithsonian'^institution i^ 33 . z I/' ^ ^ (^ RIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS S3lbVHan Li CO — -- — "> — IISNI NVINOSHimS S3IMVHan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION N' 2 -J 2 _j 2 RIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIifllliSNI NVINOSHIIWS SSIMVyail L! MOTITI IT I f\t _NviN0SHiiws'^S3iMvaan libraries'^smithsonian^institution NOlin z \ '^ ^—s^ 5 <^ ^ ^ ^ '^ - /^w\ ^ /^^\ - ^^ ^ /^rf^\ - /^ o ^^^ — x.ii:i2Ji^ o ??'^ — \ii Z ^^^^^""-^ o ^^^^^ -» 2 _J Z -J , ; SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIXniliSNI NVINOSHillMS $3 I M VH 8 !!_ LI BR = C/> ± O) ^. ? CO I NVINOSHimS S3iaVHan libraries SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIlf CO ..-. CO 2 Z z . o .3 :/.^ C/)o Z u. ^^^ i to Z CO • z to * z > SMITHS0NIAN_1NSTITUTI0N NOIiniliSNI_NVINOSHimS S3 I d ViJ 8 n_LI B R UJ i"'NViNOSHiiws S3ibvyan libraries smithsonian"^institution Noiir r~ > z r- Z r- 2: . CO . ^ ^ ^ ^ ; SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHillNS SSiyVMail LI BR CO . •» Z r, <^ 2 z 5 ^^4ii?^^ ^' X^W o ^"^- x life ^<ji; o ^'f;0: i >^ _NVIN0SHiIlMs'^S3iyVdan^LIBRARIEs'^SMITHS0NlAN INSTITUTION NOlif Z \ ^'^ ^-rr-^ 5 CO n CO CO o z > SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHimS S3 I ^Vd 8 11 LI BR >" _ . z 3 ENTOMOLOGIST'S RECORD AND Journal of Variation Edited by P.A. SOKOLOFF fre s Assistant Editors J.A. -

Karen Eastwood Registry Officer

Page 1 of 2 Archived: 16 September 2019 16:23:08 From: [email protected] Sent: 16 September 2019 13:26:01 To: Registry Dingwall Cc: marine. planning@shetland. gov.uk Subject: CAR/L/1185816 - Wick of Gruting Marine Pen Fish Farm, Fetlar, Shetland Importance: Normal Hi Karen, Thanks for this. The corresponding planning application ( Ref: 2019/ 012/ MAR) is currently under determination by Shetland Islands Council. The application was validated on 5th July 2019, and we hope to make a decision within the statutory 4 month period (by/ before 4th November 2019). The application details, and correspondence received to date can be viewed on our website at: https:// pa.shetland. gov.uk/ online-applications/ search. do?action=simple& searchType= Application https:// pa.shetland. gov.uk/ online-applications/ applicationDetails. do? keyVal= PU47YROA02300& activeTab= summary Regards Simon Simon Pallant | Coastal Zone Manager – Marine Planning | Shetland Islands Council | Development Services 8 North Ness Business Park | Lerwick | Shetland | ZE1 0LZ Tel: 01595 744805 From: Registry Dingwall [ mailto: registrydingwall@sepa. org.uk] Sent: 16 September 2019 10:59 To: Marine Planning@Development Services < marine. planning@shetland. gov.uk> Subject: CAR/ L/ 1185816 - Wick of Gruting Marine Pen Fish Farm, Fetlar, Shetland Hi, Please see attached consultation request for an application for CAR/ L/ 1185816. https:// www.sepa.org.uk/ regulations/ consultations/ advertised- applications- under-car/ Thanks Karen Karen Eastwood Registry Officer Dingwall Registry Scottish Environment Protection Agency, Graesser House, Fodderty Way, Dingwall, IV15 9XB tel: 01349 862021 dd: 01349 860384 e-mail: registrydingwall@sepa. org.uk; www.sepa.org.uk The information contained in this response relates to only information held on SEPA’ s Public Register as required by the relevant Legislation. -

TINGWALL: the SIGNIFICANCE of the NAME Gillian Fellows-Jensen

TINGWALL: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE NAME Gillian Fellows-Jensen Introduction: thing and ting1 In present-day English the word thing means 'an entity of any kind', concrete or abstract, as in the pronouns anything, something or nothing. It can even be used as a term of endearment, at least to those not in a position to remonstrate, for example Alice in Wonderland, into whose arm the Duchess tucked her arm affectionately, saying 'You can't think how glad I am to see you again, you dear old thing!' In the modem Scandinavian languages, too, the cognate word ting has the same all-embracing kind of meaning and is found in pronouns such as Danish nogenting 'anything' and ingenting 'nothing'. When used of a person, however, it is generally in a derogatory sense, referring mainly to women who are old, ugly or loose-living or perhaps all three at once (ODS s.v. ting). As a place-name specific or generic, it is clear that thing must have a concrete significance. There are a number of field-names recorded in Middle English and early Modern English sources in which it is compounded with a personal name or a term denoting a human-being and seems to have the sense 'possession'. The earliest example I have noted is Aynoifesthyng 1356 in Ash in Surrey (Gover et al. 1933: 270) but the vast majority of occurrences date from the 15th to the l 7th centuries. In Old English and the other early Germanic languages, however, the word thing and its cognates, which were all of neuter gender, had the meaning 'assembly, meeting' and it is from this meaning that the modern, more general meaning has developed. -

Toward a Broadband Public Interest Standard Anthony E

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2009 Toward a Broadband Public Interest Standard Anthony E. Varona American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Communications Law Commons Recommended Citation Varona, Anthony E. “Toward a Broadband Public Interest Standard.” Administrative Law Review 61, no. 1 (2009): 1-136. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES TOWAm A BROADBAND PUBLIC INTEMST STANDAm Introduction ...................................................................................................3 I. The Broadcast Public Interest Standard ..........................................11 A. Statutorgr and Regulatav Founttations ......................................1 1 B. Defining ""Public Interest" in Broadcasting ............................... 12 1. 1930s Through 1960s-Proactive Regulation "to Promote and Realize the Vast Potentialities'kof Broadcasting .................,...............................................