You Can Download This Book Here in Pdf Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bakery Price List

BAKERY GOODS ROLLS PRICE SLICED BREAD PRICE MORNING ROLL £0.31 HOMESTYLE WHITE 800G £2.00 WHEATEN ROLL £0.36 RICH FRUIT LOAF £2.45 BARM £0.35 MULTISEED 800G £2.38 BURGER ROLL £0.35 COUNTRY COARSE 400G £1.90 GRANARY ROLL £0.36 CRUSTY 400G £1.90 ROUGH W/MEAL ROLL £0.35 GLENCRUST 400G £2.00 CRACKED WHEAT ROLL £0.35 WHEATMEAL 400G £1.76 TRADITIONAL ROLL £0.32 BERRYMEAL 400G £2.00 CHEESY BAP £0.42 CRUSTY 800G £2.80 POPPYSEED FINGER £0.35 RUSTIC 800G £2.95 WHITE DINNER ROLL £0.26 RUSTIC 400G £2.00 BROWN DINNER ROLL £0.26 HERB & ONION 400G £2.05 FYNE HERB & ONION DINNER ROLL £0.28 BROWN SANDWICH LOAF 800G £2.00 WHITE SUB £0.45 SOFTIE £0.35 NEW YORK HOT DOG ROLL £0.40 TEABREAD BRIOCHE ROLL £0.62 OATIE SUB £0.45 PLAIN COOKIE £0.40 HERB & ONION SUB £0.45 FARM SCONE £0.78 LARGE POPPYSEED SUB £0.45 COTTAGE SCONE £0.50 SULTANA SCONE £0.50 BREAD POTATO SCONE £0.33 CRUMPET £0.50 CRUSTY 400G £1.90 HOT X BUN £0.42 GLENCRUST 400G £2.00 PANCAKE £0.48 BERRYMEAL 400G £2.00 CROISSANT £0.56 BAGUETTE £2.00 WHEATMEAL 400G £1.76 COUNTRY COARSE 400G £1.90 HERB & ONION 400G £2.05 RICH FRUIT LOAF £2.45 DO-NUTS RUSTIC 800G £2.95 CRUSTY 800G £2.80 SUGAR RING DO-NUT £0.54 BROICHE LOAF 400G £1.90 ICED DO-NUT £0.70 RUSTIC 400G £2.00 JAM BALL DO-NUT £0.70 PASTRIES PRICE CONFECTIONERY SMALL PRICE CAKES APPLE TART S/CRUST £2.65 CHOCOLATE & MARZIPAN £0.86 LOG RHUBARB TART S/CRUST £2.65 FRENCH CAKE £0.80 DANISH PASTRY £0.94 TOFFEE SLICE £0.82 APPLE TURNOVER £1.06 ICED GINGER SLICE £0.80 CHELSEA BUN £0.94 FERN CAKE £0.72 APPLE & CUSTARD DANISH £1.06 PINEAPPLE PEAK £0.78 RASPBERRY -

Breakfast Order Order a Breakfast Menu (See the Back) Or/And a Selection of Freshly Baked Bread, Drinks, Marmelade, Cheese Etc

Breakfast order Order a breakfast menu (see the back) or/and a selection of freshly baked bread, drinks, marmelade, cheese etc. Give the order form to our receptionist or put it in the mailbox in the entrance before 06.00 a.m. It will be ready for You at 8 a.m. in the reception. 1. Fill in the information Order for the following day : Date : Holiday Home number: Name: 2. Choose from our freshly baked and delicious rolls and bread Eco rye bread roll Eco rye with sesame Baked with rye and Price DKK 8 /each Baked with rye. Price DKK 8 /each sprinkled with oat flakes Delicious nutty flavor and pumpkin seeds Pieces__________ from roasted sesame Pieces __________ seeds. 01 06 Skagen roll Roll, rustic dark Light and airy with a crisp Handmade with depth Price DKK 8 /each Price DKK 8 /each crust. Sunflower seeds at and sweetness from rye the bottom. Topped with flour and toasted malt. Pieces __________ Pieces __________ poppyseed and sesame Baked on baking stone 02 07 seeds Skagen roll, full-grain Spanish roll, rustic Topped with oat flakes Price DKK 8 /each Light and rustic Price DKK 8 /each and with sunflower morning roll with a thin seeds at the bottom. Pieces __________ crisp crust Pieces __________ 03 08 Butterbread Dark butterbread Crisp roll topped Tasty and airy with Price DKK 8 /each Price DKK 8 /each with poppies and filled oat flakes and linseed. Pieces __________ with sweet and Pieces __________ Coarse and crisp. caramelized remonce. 04 09 Mini Roll Price DKK 5 /each Bianca piece Baked on stone plate. -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

Trish Reid, Theatre & Scotland (Houndmills

Ian Brown, editor, The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011); Trish Reid, Theatre & Scotland (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) Alan Riach What might be described as the conventional wisdom about Scottish drama is summed up in the first two sentences of chapter 10 of Marshall Walker’s book, Scottish Literature since 1707 (1996): ‘There is no paucity of Scottish theatrical heritage, but there is a shortage of durable Scottish plays. Drama is the genre in which Scottish writers have shown least distinction.’ It is a judgement that has been perpetuated over generations but only relatively recently has the necessary scholarship and engagement been advanced, by both academics and theatre practitioners, to interrogate the assumptions that lie behind it. Walker refers to ‘the circumstances of theatrical history’ and questions of suppression and censorship, the Reformation, the removal of the court to London in 1603, the Licensing Act of 1737, and concludes his introduction to the chapter by saying that despite familiar references to Allan Ramsay, John Home, Joanna Baillie, and the vitality of folk, music-hall and variety theatre, nothing much happens between Sir David Lyndsay in the sixteenth century and the ‘return’ of Scottish drama in the twentieth century. Most of his chapter then goes on to discuss incisively and refreshingly the achievements of J.M. Barrie, James Bridie and John McGrath but the context he sketches out is barren. As a summary, there is some brutal truth in this, but as an appraisal of the whole complex story, there is much more to be said, and much more has been discovered and made public in the decades since Walker’s book appeared. -

ORKNEY BOOKS CATALOGUE SEPTEMBER 2021 Please Email Queries to Bi [email protected] Or Telephone 07496 122658

ORKNEY BOOKS CATALOGUE SEPTEMBER 2021 Please email queries to bi [email protected] Or telephone 07496 122658 Around Orkney; A Picture Guide. Lerwick: Shetland Times Ltd, 2001. 1st Edition. ISBN: 1 898852 77 4. Very good. Softcover. (339) £2.00 Illustrated Guide to Orkney. Kirkwall: John Mackay, Ca 1918. Early guide published by the proprietor of Kirkwall and Stromness hotels (and with numerous adverts for the same). Some great photographs including the 'cromlech' at Brodgar and harbours at Stromness and Kirkwall. Scarce. Good +. Softcover. (3788) £20.00 Institute of Geological Sciences. One Inch Series. Scotland Sheet 120. Southampton: Director General - Ordnance Survey, 1932. Covers eastern part of Orkney Islands including Stronsay and Shapinsay. Based on the 1910 revision. Very good +. (1624) £5.00 Institute of Geological Sciences. One inch series. Scotland Sheet 122 - Sanday. Southampton: Director General - Ordnance Survey, 1932. Drift Edition. Based on the 1910 revision. Very good. (1628) £5.00 Magnus in Orkney Looking at Nature; A Story Book with Pictures to Colour. Kirkwall: Orkney Pre-School Play Association, 1989. ISBN: 0951356917. Small mark on front cover otherwise unused. Very good +. Softcover. (4961) £0.10 New North 2. The Magazine of Aberdeen University Literary Society. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Literary Society, 1967. 1st Edition. With introduction to, and short piece of writing by, George Mackay Brown. Clean copy - some marking around the staples. Good. Softcover staple bound. (4824) £1.00 Orkney Economic Review No 17. Kirkwall: Orkney Islands Council, 1997. 1st Edition. Near fine. Softcover. (4957) £0.50 Orkney Heritage Volume 1. Kirkwall: Orkney Heritage Society, 1981. 1st Edition. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer The field of play Citation for published version: McDowell, M 2014, 'The field of play: Phases and themes in the historiography of pre-1914 Scottish football', The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 31, no. 17, pp. 2121-2140. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2014.900489 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/09523367.2014.900489 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The International Journal of the History of Sport Publisher Rights Statement: © McDowell (2014). The Field of Play: Phases and Themes in the Historiography of Pre-1914 Scottish Football. The International Journal of the History of Sport. 10.1080/09523367.2014.900489 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 The field of play: phases and themes in the historiography of pre-1914 Scottish football Matthew L. McDowell University of Edinburgh Pre-publication print of: Matthew L. McDowell, ‘The field of play: phases and themes in the historiography of pre-1914 Scottish football’, The International Journal of the History of Sport (issue not yet assigned). -

Lot 0 This Is Our First Sale Catalogue of 2021. Due to the Current Restrictions

Bowler & Binnie Ltd - Antique & Collectors Book Sale - Starts 20 Feb 2021 Lot 0 This is our first sale catalogue of 2021. Due to the current restrictions, we felt this sale was the best type of sale to return with- welcome to our first ever ‘Rare & Collectable Book Sale’… Firstly, please note that all lots within this sale catalogue are used and have varying levels of use and age-related wear. However, we can inform that all entries have come from the same vendor, whom, was the owner of an established book shop. There are some new and remaining alterations that we are making to our sales, they are as follows: 1- There will continue to be no viewing for this sale. Each lot has a description based on the information we have. Furthermore, there are multiple images to accompany each lot (which can be zoomed in on). If there is a question you have (that cannot be answered through the description or images) please contact us via email. 2- The sale will continue to be held from home; however, we will be working with a further reduced workforce. We will be unable to answer phone calls on sale day and therefore ask that if you have a request for a condition report, that these are in by 12pm on Friday 19th and that all commission bids are placed by 7pm on this same date- anything received after these times, will not be accepted. 3- Due to our current reduced workforce and the restrictions, we are working with, we will only be able to pack and send individual books. -

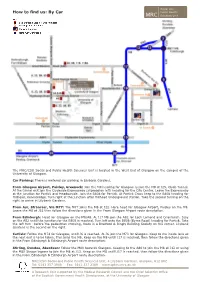

How to Find Us: by Car

How to find us: By Car The MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit is located in the West End of Glasgow on the campus of the University of Glasgow. Car Parking: There is metered car parking in Lilybank Gardens. From Glasgow Airport, Paisley, Greenock: Join the M8 heading for Glasgow. Leave the M8 at J25, Clyde Tunnel. At the tunnel exit join the Clydeside Expressway (sliproad on left) heading for the City Centre. Leave the Expressway at the junction for Partick and Meadowside. Join the B808 for Partick. At Partick Cross keep to the B808 heading for Hillhead, Kelvinbridge. Turn right at the junction after Hillhead Underground station. Take the second turning on the right to arrive in Lilybank Gardens. From Ayr, Stranraer, Via M77: The M77 joins the M8 at J22. Here head for Glasgow Airport, Paisley on the M8. Leave the M8 at J25 then follow the directions given in the From Glasgow Airport route description. From Edinburgh: Head for Glasgow on the M8/A8. At J17 M8 join the A82 for Loch Lomond and Crianlarich. Stay on the A82 untill the junction for the B808 is reached. Turn left onto the B808 (Byres Road) heading for Partick. Take the left turn before the pedestrian crossing, there is a Bradford & Bingly Building Society on the corner. Lilybank Gardens is the second on the right. Carlisle: Follow the M74 for Glasgow, untill J6 is reached. At J6 join the M73 for Glasgow. Keep to the inside lane as the next exit is to be taken. This joins the M8. -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

Scottish Language Letter Cle To

CLE [449] CLE 1 radically the same. From the form of the A.-S. word, Nor his bra targe, on which is seen it seems to have been common to the Celtic and The ycr.l, the sin, the lift, the Can well agree wi' his cair Gothic ; and probably dough had originally aamc cleuck, That cleikit was for thift. sense with Ir. rloiclte, of, or belonging to, a rock or Poems in the Buchan 12. stone. V. CLOWK. Dialect, p. This term is transferred Satchels, when giving the origin of the title Sue- to the hands from their i-li or hold of E. of niih, supplies us with a proof of clench and heuclt being griping laying objects. clutch, which neither Skinner nor Johnson is synon. : gives any etymon, evidently from the same Junius derives clutches Ami for the buck thou stoutly brought origin. from to shake ; but without reason. To us up that steep heugh, Belg. klut-en, any Thy designation ever shall Shaw gives Gael, glaic as signifying clutch. Somner Be John Scot in [ot\Buckscleugh. views the E. word as formed from A.-S. gecliht, "col- History Jfame of Scot, p. 37. lectus, gathered tegether : hand gecliht, manus collecta vel contracta," in modern language, a clinched fat. CLEUCII, adj. 1. Clever, dextrous, light- But perhaps cleuk is rather a dimin. from Su.-G. klo, fingered. One is said to have cleuch hands, Teut. klaawe, a claw or talon. Were there such a word as Teut. as from or to be "cleuch of the fingers," who lifts klugue, unguis, (mentioned GL the resemblance would be so that do not Kilian, Lyndsay, ) greater. -

Reserve Cup Fixtures 2018/19

RD DAY DATE COMPETITION HOME AWAY VENUE KO 1 MON 10/09/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group A Dundee United v St. Johnstone St Andrews University 2pm 1 MON 10/09/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group A St. Mirren v Hamilton Academical Simple Digital Arena 2pm 1 MON 10/09/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group B Celtic v Aberdeen Cappielow Park 2pm 1 MON 10/09/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group B Falkirk v Ross County Falkirk Stadium 2pm 1 MON 10/09/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group C Hibernian v Heart of Midlothian Oriam 2pm 1 MON 10/09/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group C Kilmarnock v Partick Thistle Rugby Park 2pm 1 MON 10/09/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group D Dunfermline Athletic v Queen of the South New Central Park 2pm 1 MON 10/09/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group D Motherwell v Dundee Forthbank Stadium 2pm 2 MON 08/10/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group A Hamilton Academical v Dundee United New Douglas Park 2pm 2 MON 08/10/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group A St. Johnstone v St. Mirren McDiarmid Park 2pm 2 MON 08/10/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group B Aberdeen v Falkirk Balmoral Stadium 2pm 2 MON 08/10/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group B Ross County v Celtic Highland Football Academy 2pm 2 MON 08/10/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group C Heart of Midlothian v Kilmarnock Oriam 2pm 2 MON 08/10/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group C Partick Thistle v Hibernian Lesser Hampden 2pm 2 MON 08/10/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group D Dundee v Morton Links Park 2pm 2 MON 08/10/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group D Queen of the South v Motherwell Palmerston Park 2pm 3 MON 15/10/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group D Morton v Queen of the South Cappielow Park 2pm 3 MON 15/10/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group D Motherwell v Dunfermline Athletic Forthbank Stadium 2pm 4 MON 05/11/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group D Dunfermline Athletic v Morton New Central Park 2pm 4 MON 05/11/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group D Queen of the South v Dundee Palmerston Park 2pm 5 MON 12/11/2018 SPFL Reserve Cup Group A Dundee United v St.