UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

RHETORIC and RATIONALITY Steve Mackey

Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, vol. 9, no. 1, 2013 RHETORIC AND RATIONALITY Steve Mackey ABSTRACT: The dominance of a purist, ‘scientistic’ form of reason since the Enlightenment has eclipsed and produced multiple misunderstandings of the nature, role of and importance of the millennia-old art of rhetoric. For centuries the multiple perspectives conveyed by rhetoric were always the counterbalance to hubristic claims of certainty. As such rhetoric was taught as one of the three essential components of the ‘trivium’ – rhetoric, dialectic and grammar; i.e. persuasive communication, logical reasoning and the codification of discourse. These three disciplines were the legs of the three legged stool on which western civilisation still rests despite the perversion and muddling of the first of these three. This essay explains how the evisceration of rhetoric both as practice and as critical theory and the consequent over- reliance on a virtual cult of rationality has impoverished philosophy and has dangerously dimmed understandings of the human condition. KEYWORDS; Rhetoric; Dialectic; Rationality; Enlightenment; Philosophy; Communication; C.S.Peirce: Max Horkheimer; Theodor Adorno; Jürgen Habermas; John Deely THE PROBLEM There are many criticisms of the rationalist themes and approaches which burgeoned during and since the Enlightenment. This paper enlists Max Horkheimer (1895 – 1973) and Theodor Adorno (1903 – 1969), John Deely (1942 – ) and Charles Sanders Peirce (1839 –1914), along with some leading Enlightenment figures themselves in order to mount a critique of the fate of the millennia-old art of rhetoric during that revolution in ways of thinking. The argument will be that post-Enlightenment over- emphasis on what might variously be called dialectic, logic or reason (narrowly understood) has dulled understanding of what people are and how people think. -

Perceptive Intent in the Works of Guenter Grass: an Investigation and Assessment with Extensive Bibliography

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Perceptive Intent in the Works of Guenter Grass: an Investigation and Assessment With Extensive Bibliography. George Alexander Everett rJ Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Everett, George Alexander Jr, "Perceptive Intent in the Works of Guenter Grass: an Investigation and Assessment With Extensive Bibliography." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1980. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1980 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 71-29,361 EVERETT, Jr., George Alexander, 1942- PRECEPTIVE INTENT IN THE WORKS OF GUNTER GRASS: AN INVESTIGATION AND ASSESSMENT WITH EXTENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. PRECEPTIVE INTENT IN THE WORKS OF GUNTER GRASS; AN INVESTIGATION AND ASSESSMENT WITH EXTENSIVE BIBIIOGRAPHY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Foreign Languages by George Alexander Everett, Jr. B.A., University of Mississippi, 1964 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1966 May, 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

1964 Jaargang 19 (Xix)

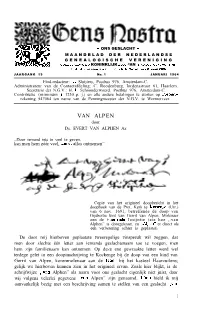

- ONS GESLACHT - MAANDBLAD DER NEDERLANDSE GENEALOGISCHE VERENIGING OOEDGEKEURD 312 KONINKLIJK BESL. “AN 16 A”O”STUS reaa. YO. 85 Llc.tstel,jk podpeKe”rd 51, KO”i”kli,k a.,,uit van J .+r,, ,833 JAARGANG 19 No. 1 JANUARI 1964 Eind-redacteur: J. Sluijters, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Administrateur van de Contactafdeling: C. Roodenburg, Iordensstraat 61, Haarlem. Secretaris der N.G.V.: H. J. Schoonderwoerd, Postbus 976, Amsterdam-C. Contributie (minimum f 1230 p. j.) en alle andere betalingen te storten op Postgiro- rekening 547064 ten name van de Penningmeester der N.G.V. te Wormerveer. VAN ALPEN door Ds. EVERT VAN ALPHEN Az ,,Door iemand iets te veel te geven, kan men hem zéér veel, zoniet alles ontnemen” Copie van het origineel doopbericht in het doopboek van de Prot. Kerk te Kortenge (Utr.) van 6 nov. 1691, betreffende de doop van Gijsbertie kint van Gerrit van Alpen, Molenaer aen de Haer ende Josijntie (zie hoe ,,van Alphen” is doorgekrast, en ,,Alpen” er direct als een verbetering achter is geplaatst). De door mij hierboven geplaatste tweeregelige zinspreuk wil zeggen, dat men door slechts één letter aan iemands geslachtsnaam toe te voegen, men hem zijn familienaam kan ontnemen. Op deze ene gewraakte letter werd wel terdege gelet in een doopinschrijving te Kockenge bij de doop van een kind van Gerrit van Alpen, korenmolenaar aan de Haer bij het kasteel Haarzuilens; gelijk we hierboven kunnen zien in het origineel ervan. Zoals hier blijkt, is de schrijfwijze ,,van Alphen” als naam voor ons geslacht eigenlijk niet juist, daar wij volgens velerlei gegevens ,,van Alpen” zijn genaamd. -

Board of the International Association for Cognitive Semiotics

Book of Abstracts for the 3rd Conference of the International Association for Cognitive Semiotics Multimodalities Book of Abstracts for the 3rd Conference of the International Association for Cognitive Semiotics Multimodalities Toronto, Ontario (Canada) July 13–15, 2018 IACS-2018: Third Conference of the International Association for Cognitive Semiotics | 1 Local Organizing Committee of IACS-2018 Some rights reserved. Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Among other sponsors, this project was made possible by funding from the Dean of the Faculty of Arts, Ryerson University, in addition to funding from the Ryerson University Office of the Vice President for Research and Innovation and the Ryerson University Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures, including a Knowledge Dissemination Grant (KDG), an Undergraduate Research Opportunity Grant (URO) and an Event Funding Grant. Please see the back cover of this manuscript for a full list of project partners. No responsibility is assumed by the IACS-2018 Local Organizing Committee for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of product liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions or ideas contained in the material herein. Printed in Toronto, Ontario (Canada) 2 | IACS-2018: Third Conference of the International Association for Cognitive Semiotics About the International Association for Cognitive Semiotics The International Association for Cognitive Semiotics (IACS) was founded in 2013 at Aarhus University, Denmark, in connection with the Eighth Conference of the Nordic Association for Semiotic Studies (NASS). Cognitive semiotics is the study of meaning-making, both in language and by means of other sign vehicles, as well as in perception, and in action. -

Averroes's Dialectic of Enlightenment

59 AVERROES'S DIALECTIC OF ENLIGHTENMENT. SOME DIFFICULTIES IN THE CONCEPT OF REASON Hubert Dethier A. The Unity ofthe Intellect This theory of Averroes is to be combated during the Middle ages as one of the greatest heresies (cft. Thomas's De unitate intellectus contra Averroystas); it was active with the revolutionary Baptists and Thomas M"Unzer (as Pinkstergeest "hoch liber alIen Zerstreuungen der Geschlechter und des Glaubens" 64), but also in the "AufkHinmg". It remains unclear on quite a few points 65. As far as the different phases of the epistemological process is concerned, Averroes reputes Avicenna's innovation: the vis estimativa, as being unaristotelian, and returns to the traditional three levels: senses, imagination and cognition. As far as the actual abstraction process is concerned, one can distinguish the following elements with Avicenna. 1. The intelligible fonns (intentiones in the Latin translation) are present in aptitude and in imaginative capacity, that is, in the sensory images which are present there; 2. The fonns are actualised by the working of the Active Intellect (the lowest celestial sphere), that works in analogy to light ; 3. The intelligible fonns-in-act are "received" by the "possible" or the "material intellecf', which thereby changes into intellect-in-act, also called: habitual or acquired intellect: the. perfect form ofwhich - when all scientific knowledge that can be acquired, has been acquired -is called speculative intellect. 4. According to the Aristotelian principle that the epistemological process and knowing itselfcoincide, the state ofintellect-in-act implies - certainly as speculative intellect - the conjunction with the Active Intellect. 64 Cited by Ernst Bloch, Avicenna und die Aristotelische Linke, (1953), in Suhrkamp, Gesamtausgabe, 7, p. -

Kopstukken Van De Nsb

KOPSTUKKEN VAN DE NSB Marcel Bergen & Irma Clement Marcel Bergen & Irma Clement KOPSTUKKEN VAN DE NSB UITGEVERIJ MOKUMBOOKS Inhoud Inleiding 4 Nationaalsocialisme en fascisme in Nederland 6 De NSB 11 Anton Mussert 15 Kees van Geelkerken 64 Meinoud Rost van Tonningen 98 Henk Feldmeijer 116 Max Blokzijl 132 Robert van Genechten 155 Johan Carp 175 Arie Zondervan 184 Tobie Goedewaagen 198 Henk Woudenberg 210 Evert Roskam 222 Noten 234 Literatuur 236 Colofon 238 dwang te overtuigen van de Groot-Germaanse gedachte. Het gevolg is dat Mussert zich met enkele getrouwen terug- trekt op het hoofdkwartier aan de Maliebaan in Utrecht en de toenemende druk probeert te pareren met notities, toespraken en concessies. Naarmate de bezetting voortduurt nemen de concessies die Mussert aan de Duitse bezetter doet toe. Inleiding De Nationaal Socialistische Beweging (NSB) speelt tijdens Het Rijkscommissariaat de Tweede Wereldoorlog een opmerkelijke rol. Op 14 mei 1940 aanvaardt Arthur Seyss-Inquart in de De NSB, die op 14 december 1931 in Utrecht is opgericht in Ridderzaal de functie van Rijkscommissaris voor de een zaaltje van de Christelijke Jongenmannen Vereeniging, bezette Nederlandse gebieden. Het Rijkscommissariaat vecht tijdens haar bestaan een richtingenstrijd uit. Een strijd is een civiel bestuursorgaan en bestaat verder uit: die gaat tussen de Groot-Nederlandse gedachte, die streeft – Friederich Wimmer (commissaris-generaal voor be- naar een onafhankelijk Groot Nederland binnen een Duits stuur en justitie en plaatsvervanger van Seyss-Inquart). Rijk en de Groot-Germaanse gedachte,waarin Nederland – Hans Fischböck (generaal-commissaris voor Financiën volledig opgaat in een Groot-Germaans Rijk. Niet alleen de en Economische Zaken). richtingenstrijd maakt de NSB politiek vleugellam. -

Conceptions of Terror(Ism) and the “Other” During The

CONCEPTIONS OF TERROR(ISM) AND THE “OTHER” DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF THE RED ARMY FACTION by ALICE KATHERINE GATES B.A. University of Montana, 2007 B.S. University of Montana, 2007 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures 2012 This thesis entitled: Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction written by Alice Katherine Gates has been approved for the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures _____________________________________ Dr. Helmut Müller-Sievers _____________________________________ Dr. Patrick Greaney _____________________________________ Dr. Beverly Weber Date__________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Gates, Alice Katherine (M.A., Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures) Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction Thesis directed by Professor Helmut Müller-Sievers Although terrorism has existed for centuries, it continues to be extremely difficult to establish a comprehensive, cohesive definition – it is a monumental task that scholars, governments, and international organizations have yet to achieve. Integral to this concept is the variable and highly subjective distinction made by various parties between “good” and “evil,” “right” and “wrong,” “us” and “them.” This thesis examines these concepts as they relate to the actions and manifestos of the Red Army Faction (die Rote Armee Fraktion) in 1970s Germany, and seeks to understand how its members became regarded as terrorists. -

Theodor W. Adorno)

Conclusion: Speaking of the Noose in the Country of the Hangman (Theodor W. Adorno) I deny that there has ever been such a German-Jewish dialogue in any genuine sense whatsoever, i.e., as a historical phenomenon . It takes two to have a dialogue, who listen to each other, who are prepared to perceive the other as what he is and represents, and to respond to him. Nothing can be more misleading than to apply such a concept to the discussions between Germans and Jews during the last 200 years. —Gershom Scholem, Against the Myth of the German-Jewish Dialogue This book would not be complete without a consideration of Theodor W. Adorno’s role in the formation of a public discourse on the Holocaust in postwar Ger- many. There are multiple reasons for this. Adorno’s presence loomed large in the new republic’s sociopolitical and intellectual landscape. During the 1950s and 1960s he gave over three hundred public speeches and delivered about as many radio lectures, prompting some to speak of a veritable Adorno-infl ation.1 Adorno could be heard—and was indeed listened to—on an almost weekly basis. 2 1. Quoted in Michael Schwarz, “ ‘Er redet leicht, schreibt schwer’: Theodor W. Adorno am Mikro- phon,” Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History , Online-Ausgabe, 8 (2011): 1, http:// www.zeithistorische-forschungen.de/16126041-Schwarz-2-2011 . 2. Schwarz, “ ‘Er redet leicht, schreibt schwer.’ ” 196 Speaking the Unspeakable in Postwar Germany Evidently this aural and performative aspect of his public engagement was impor- tant to Adorno, who did not want to be reduced to the role of a writer. -

245 LIST A'brakel, Wilhelmus the Christian's Reasonable Service

LIST 245 1. A’BRAKEL, The Christian’s Reasonable Service. S.D.G.-1992. d.w’s. 4 £ 45.00 Wilhelmus volumes. ills. 2. ADAMS, J. E. The Time is at Hand. Prophecy and the Book of Revelation. £ 3.95 Timeless Texts-2000. lfpb. 16+138pp. 3. ADAMS, J. E. A Theology of Christian Counselling More than Redemption. £ 4.95 Zon.-1979 lfpb. 338pp. 4. ADAMS, J. E/FISHER The Time of the End. Daniel’s Prophecy Reclaimed. Timeless £ 3.95 Text-2000. lfpb. 120pp. Frwd. by R. C. Sproul. 5. ADAMS, J. G. The Big Umbrella. (Christian Counselling) BBH.-1975. lfpb. £ 4.50 265pp. 6. ALLISON, D.C Jesus of Nazareth Millenarian Prophet. Fortress-1998. lfpb. £ 4.50 255pp. 7. ALTHUSIUS, J. (1557 Politica. An abridged translation of Politics methodically set £ 8.50 -1638) forth and illustrated with Sacred and Profane examples. Trans. by F. S. Carney. Liberty -1995. lfpb. 62+238pp. From 1614 edition. 8. ALVARDO, R. A Common Law, the Law of Nations and Western Civilization. £ 3.50 Pietas-1999. lfpb. 161pp. 9. AMBROSE, Isaac Looking Unto Jesus. A View of the Everlasting Gospel etc. £ 8.00 Sprinkle-1986. hb. 694pp. Large volume, Puritan devotional classic. 10. ANON The Truth of the History of the Gospel Made Out by Heathen £ 22.00 Evidence. Edin.-1741. 38pp. XL. Pam. 11. ANON Queries Concerning the Reasonableness of Reclaiming the £ 22.00 Corporation Test Acts as Far as They Relate to Protestant Dissenters. Lon.-1732. 23pp. XL. Pam. Scarce. 12. ASHTON John F. Edt. In Six Days: Why 50 Scientists choose to Believe in Creation. -

Chiasmus in Ancient Greek and Latin Literatures

Chiasmus in Ancient Greek and Latin Literatures John W. Welch Notwithstanding the fact that most recent scholarly attention has dealt with the occurrence of chiasmus in ancient Near Eastern languages and literatures, a signicant amount of chiasmus is to be found in ancient Greek and Latin literatures as well. Indeed, the word ,,chiasmus” itself stems from the Greek word chiazein, meaning to mark with or in the shape of a cross, and chiasmus has been earnestly studied in Greek and Latin syntax and style far more extensively and many years longer than is has even been acknowledged in the context of Semitic and other ancient writings. That chiasmus has received more attention in the Classical setting than in other ancient literatures is at the same time both ironic and yet completely understandable. The irony lies in the fact that more scholarly acceptance and utilization of chiasmus is found in connection with the appreciation of Western literary traditions than in the study of other ancient literatures, whereas chiasmus is relatively simple and certainly less informative in respect to the Greek and Latin authors than it is in regard to many of the writers from other arenas of the ancient world. One would expect the greater efforts to be made where the rewards promise to be the more attractive. Yet this situation is also easily explained. For one thing, numerous Western scholars have exhaustively studied secular Greek literary texts since the thirteenth century, and Latin, since it was spoken in Rome. The use of literary devices in Hebrew literature, on the other hand, has only been given relatively sparse scholarly treatment in the West for something over two hundred years, and the study of gures of speech in most other ancient languages, dialects and literatures can still be said to be somewhat in a state of infancy. -

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 By

The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair Professor John F. Connelly Professor Jeroen Dewulf Professor David W. Bates Spring 2012 Abstract The Actuality of Critical Theory in the Netherlands, 1931-1994 by Nicolaas Peter Barr Clingan Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Martin E. Jay, Chair This dissertation reconstructs the intellectual and political reception of Critical Theory, as first developed in Germany by the “Frankfurt School” at the Institute of Social Research and subsequently reformulated by Jürgen Habermas, in the Netherlands from the mid to late twentieth century. Although some studies have acknowledged the role played by Critical Theory in reshaping particular academic disciplines in the Netherlands, while others have mentioned the popularity of figures such as Herbert Marcuse during the upheavals of the 1960s, this study shows how Critical Theory was appropriated more widely to challenge the technocratic directions taken by the project of vernieuwing (renewal or modernization) after World War II. During the sweeping transformations of Dutch society in the postwar period, the demands for greater democratization—of the universities, of the political parties under the system of “pillarization,” and of