Crafting Your Father's Idol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bud Fisher—Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Winter 1979 Bud Fisher—Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists Ray Thompson Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Thompson, Ray. "Bud Fisher—Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists." The Courier 16.3 and 16.4 (1979): 23-36. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 0011-0418 ARCHIMEDES RUSSELL, 1840 - 1915 from Memorial History ofSyracuse, New York, From Its Settlement to the Present Time, by Dwight H. Bruce, Published in Syracuse, New York, by H.P. Smith, 1891. THE COURIER SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES Volume XVI, Numbers 3 and 4, Winter 1979 Table of Contents Winter 1979 Page Archimedes Russell and Nineteenth-Century Syracuse 3 by Evamaria Hardin Bud Fisher-Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists 23 by Ray Thompson News of the Library and Library Associates 37 Bud Fisher - Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists by Ray Thompson The George Arents Research Library for Special Collections at Syracuse University has an extensive collection of original drawings by American cartoonists. Among the most famous of these are Bud Fisher's "Mutt and Jeff." Harry Conway (Bud) Fisher had the distinction of producing the coun try's first successful daily comic strip. Comics had been appearing in the press of America ever since the introduction of Richard F. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

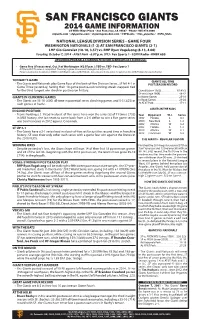

NLDS Notes GM 4.Indd

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2014 GAME INFORMATION 24 Willie Mays Plaza •San Francisco, CA 94107 •Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com •sfgigantes.com •sfgiantspressbox.com •@SFGiants •@los_gigantes• @SFG_Stats NATIONAL LEAGUE DIVISION SERIES - GAME FOUR WASHINGTON NATIONALS (1-2) AT SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (2-1) LHP Gio Gonzalez (10-10, 3.57) vs. RHP Ryan Vogelsong (8-13, 4.00) Tuesday, October 7, 2014 • AT&T Park • 6:07 p.m. (PT) • Fox Sports 1 • ESPN Radio • KNBR 680 UPCOMING PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS & BROADCAST SCHEDULE: • Game Five (if necessary), Oct. 9 at Washington (#2:07p.m.): TBD vs. TBD- Fox Sports 1 # If the LAD/STL series is completed, Thursday's game time would change to 5:37p.m. PT Please note all games broadcast on KNBR 680 AM (English radio) and ESPN Radio. All postseason home games broadcast on 860 AM ESPN Deportes (Spanish radio). TONIGHT'S GAME GIANTS ALL-TIME • The Giants and Nationals play Game Four of this best-of- ve Division Series...SF fell 4-1 in POSTSEASON RECORD Game Three yesterday, having their 10-game postseason winning streak snapped, tied for the third-longest win streak in postseason history. Overall (since 1900) . 87-83-2 SF-era (since 1958) . .48-42 GIANTS IN CLINCHING GAMES In Home Games . .25-18 • The Giants are 15-10 (.600) all-time in potential series clinching games and 5-3 (.625) in In Road Games. .23-24 such games at home. At AT&T Park . .17-11 GIANTS IN THE NLDS IN GOOD POSITION • Teams holding a 2-1 lead in a best-of- ve series have won the series 52 of 71 times (.732) Year Opponent W-L Series in MLB history...the last team to come back from a 2-0 de cit to win a ve game series 1997 Florida L 0-3 was San Francisco in 2012 against Cincinnati. -

By Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis

America’s Pastime: How Baseball Went from Hoboken to the World Series An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis Advisor Dr. Bruce Geelhoed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2020 Expected Date of Graduation July 2020 Abstract Baseball is known as “America’s Pastime.” Any sports aficionado can spout off facts about the National or American League based on who they support. It is much more difficult to talk about the early days of baseball. Baseball is one of the oldest sports in America, and the 1800s were especially crucial in creating and developing modern baseball. This paper looks at the first sixty years of baseball history, focusing especially on how the World Series came about in 1903 and was set as an annual event by 1905. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Carlos Rodriguez, a good personal friend, for loaning me his copy of Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary, which got me interested in this early period of baseball history. I would like to thank Dr. Bruce Geelhoed for being my advisor in this process. His work, enthusiasm, and advice has been helpful throughout this entire process. I would also like to thank Dr. Geri Strecker for providing me a strong list of sources that served as a starting point for my research. Her knowledge and guidance were immeasurably helpful. I would next like to thank my friends for encouraging the work I do and supporting me. They listen when I share things that excite me about the topic and encourage me to work better. Finally, I would like to thank my family for pushing me to do my best in everything I do, whether academic or extracurricular. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

Fentttn China Communist Reactions on Cease-Fire Oiler by United Nations

•' FTtlBAY jijNE K, W BT -'rilUIKMJBTEEN lEtt^nins li^roUi - ^ Avtnifs Dslly N«t Prem Run T h t W n t h t r For Ike Weak Bndtug rsMcast m 0. a WsstlMr rnmmm Among 81 divorcee, g w t e d in June 88. 1961 Hartford Superior Court yester Enters Navy Cheney Aw A. A b o u t T o w n day were; Frances M. Whitneck FarUy cloudy today, vranm rt of JCast Hartford from Ralph E. 10,163 ICr. Mid i t o T T ^ I t o n ^ of Whitneck of Manchester, Opens Year IDDBD iTTBACTION The Hobo Shirt-1951 Variety fe n tttn partly cloudy tm lght; partly MCnIrir of fho Aodlf IM Honry iCMot r*c«iUy rotonied able cruelty, plaintiff granted 810 Boreoa of Olrealstlou Woody and warm tomorrow. •rom « auccMiful M ilnu titp to a week alimony and $16 a week Manche$ter— A City o f Village Charm > m p Otlor on the First OonnecU- for support of one child; Eleanor Representatives of Vari* sut lake la l>ltUbur»h, N. H. The T. Holden of Manchester, from Wil qus Divifions of Plonl ncsl couple hrouKht home aeverel son A. Holden of'Glastonbury. In- VOL. LXX, NO. 230 (ClBMlfled Advwttaing am Pnge 19) MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, JUNE 30, 1951 (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE nVE CENTS ;ske trout, the largest of which tolerable cruelty, plaintiff granted Are Named srslghs seven pounds ,81 a year alimony and 812 a week ^for itipport of onr child; Doriii E. Bruno Dubaldo and Robert Kul- Kanehl of Manchester, from W il The officers of the Cheney Maowskl of this town are among liam E. -

Download in Short, They Represent Hope

Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 64 NO. 4 WINTER 2010 The !"#$%Goes On Its &'($') Changes ENERGY • SPORTS • GOVERNMENT • FAMILY • SCIENCE • ARTS • POLITICS + MORE BEATS ‘to promote and elevate the standards of journalism’ Agnes Wahl Nieman the benefactor of the Nieman Foundation Vol. 64 No. 4 Winter 2010 Nieman Reports The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University Bob Giles | Publisher Melissa Ludtke | Editor Jan Gardner | Assistant Editor Jonathan Seitz | Editorial Assistant Diane Novetsky | Design Editor Nieman Reports (USPS #430-650) is published Editorial in March, June, September and December Telephone: 617-496-6308 by the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University, E-mail Address: One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098. [email protected] Subscriptions/Business Internet Address: Telephone: 617-496-6299 www.niemanreports.org E-mail Address: [email protected] Copyright 2010 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Subscription $25 a year, $40 for two years; add $10 per year for foreign airmail. Single copies $7.50. Periodicals postage paid at Boston, Back copies are available from the Nieman office. Massachusetts and additional entries. Please address all subscription correspondence to POSTMASTER: One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098 Send address changes to and change of address information to Nieman Reports P.O. Box 4951, Manchester, NH 03108. P.O. Box 4951 ISSN Number 0028-9817 Manchester, NH 03108 Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 64 NO. 4 WINTER 2010 4 The Beat Goes On—Its Rhythm Changes The Beat: The Building Block 5 The Capriciousness of Beats | By Kate Galbraith 7 It’s Scary Out There in Reporting Land | By David Cay Johnston 9 The Blog as Beat | By Juanita León 11 A Journalistic Vanishing Act | By Elizabeth Maupin 13 From Newsroom to Nursery—The Beat Goes On | By Diana K. -

Knight Templar "The Magazine for York Rite Masons - and Others, Too" NOVEMBER: November Is the Month We Salute Our Grand Commanders

Grand Master's Message for November 2005 At this most pleasant time of year, we celebrate the recent harvest and give thanks for all of God's blessings. This year should be no different. We are truly blessed in so many ways. It was my pleasure to award two Grand Master's Meritorious Service Awards to Past Grand Commanders and their Grand Commanderies, which have met the requirements for that award. The first was to Sir Knight George A. Hulsinger of the Grand Commandery of Pennsylvania. Next, an award went to Sir Knight Eugene Wright of Oregon. Congratulations to both of them for their dedicated service and efforts on behalf of their Grand Commanderies. On a sad note, I regret the loss of Sir Knight William Q. Moore, Grand Prelate of the Grand Encampment, Knights Templar of the United States of America. Bill was a great friend and one of the finest Prelates I have heard speak. For quite a few years, I thought that he was a minister. In fact, he was an accountant. His delivery was so good that he fooled a number of us. Every time I heard him do the Prelate's part, he touched my heart. I have never met a kinder Sir Knight than Bill. We who were associated with him are richer for that association. He truly lived his Masonry, and we will miss him. You will find Sir Knight Moore's In Memoriam and biography on page 9 of this issue. We extend to the family of Sir Knight Moore our deepest sympathy. -

Thesis 042813

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Utah: J. Willard Marriott Digital Library THE CREATION OF THE DOUBLEDAY MYTH by Matthew David Schoss A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History The University of Utah August 2013 Copyright © Matthew David Schoss 2013 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Matthew David Schoss has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Larry Gerlach , Chair 05/02/13 Date Approved Matthew Basso , Member 05/02/13 Date Approved Paul Reeve , Member 05/02/13 Date Approved and by Isabel Moreira , Chair of the Department of History and by Donna M. White, Interim Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In 1908, a Special Base Ball Commission determined that baseball was invented by Abner Doubleday in 1839. The Commission, established to resolve a long-standing debate regarding the origins of baseball, relied on evidence provided by James Sullivan, a secretary working at Spalding Sporting Goods, owned by former player Albert Spalding. Sullivan solicited information from former players and fans, edited the information, and presented it to the Commission. One person’s allegation stood out above the rest; Abner Graves claimed that Abner Doubleday “invented” baseball sometime around 1839 in Cooperstown, New York. It was not true; baseball did not have an “inventor” and if it did, it was not Doubleday, who was at West Point during the time in question. -

A National Tradition

Baseball A National Tradition. by Phyllis McIntosh. “As American as baseball and apple pie” is a phrase Americans use to describe any ultimate symbol of life and culture in the United States. Baseball, long dubbed the national pastime, is such a symbol. It is first and foremost a beloved game played at some level in virtually every American town, on dusty sandlots and in gleaming billion-dollar stadiums. But it is also a cultural phenom- enon that has provided a host of colorful characters and cherished traditions. Most Americans can sing at least a few lines of the song “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Generations of children have collected baseball cards with players’ pictures and statistics, the most valuable of which are now worth several million dollars. More than any other sport, baseball has reflected the best and worst of American society. Today, it also mirrors the nation’s increasing diversity, as countries that have embraced America’s favorite sport now send some of their best players to compete in the “big leagues” in the United States. Baseball is played on a Baseball’s Origins: after hitting a ball with a stick. Imported diamond-shaped field, a to the New World, these games evolved configuration set by the rules Truth and Tall Tale. for the game that were into American baseball. established in 1845. In the early days of baseball, it seemed Just a few years ago, a researcher dis- fitting that the national pastime had origi- covered what is believed to be the first nated on home soil. -

Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis

Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth–Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Before They Were Cardinals SportsandAmerican CultureSeries BruceClayton,Editor Before They Were Cardinals Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis Jon David Cash University of Missouri Press Columbia and London Copyright © 2002 by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved 54321 0605040302 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cash, Jon David. Before they were cardinals : major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. p. cm.—(Sports and American culture series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8262-1401-0 (alk. paper) 1. Baseball—Missouri—Saint Louis—History—19th century. I. Title: Major league baseball in nineteenth-century St. Louis. II. Title. III. Series. GV863.M82 S253 2002 796.357'09778'669034—dc21 2002024568 ⅜ϱ ™ This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. Designer: Jennifer Cropp Typesetter: Bookcomp, Inc. Printer and binder: Thomson-Shore, Inc. Typeface: Adobe Caslon This book is dedicated to my family and friends who helped to make it a reality This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix Prologue: Fall Festival xi Introduction: Take Me Out to the Nineteenth-Century Ball Game 1 Part I The Rise and Fall of Major League Baseball in St. Louis, 1875–1877 1. St. Louis versus Chicago 9 2. “Champions of the West” 26 3. The Collapse of the Original Brown Stockings 38 Part II The Resurrection of Major League Baseball in St. -

Golf Goods Paramount and Whippet Golf Balls And

OSVOtCO TO Sportsmen anZ Athletes Base Ball, Trap Shooting Hunting, Fishing. College Foot Ball, Golf. Laivn Tennis. Cricket, Track Athletics, Vasket Ball, Sorter. Court snnif. Billiards, Bowling, Rifle and Revolver Shooting, Automobtlmg. Yachting. Camping, Rowing, Canoeing, Motor Boating, Swimming, Motor Cycling, Polo, Harness Racing and Kennel. VOL. 67. NO, 21 PHILADELPHIA. JULY 22,1916 PRICE 5 CENTS illp:':":::;:-::>::>: George men are chased from the game, probably suspended, IN SHORT METRE when they have a righteous kick. For instance, it looked like bad judgment on the part of Bill Klem to ANAGER FIELDKR JONES, of the Browns, is chase Zimmerman last Tuesday,-as 7Am had a right M one of those veterans who thinks the game is not porting Hilt to talk and argue with the umpire, as he is captain played as intelligently as it formerly was: He said: A WEEBTLT JOUBNAL DEVOTED TO BABB BALL, TRAP of the Cubs. Tet a lot of fellows have been pulling "I have not seen many of the plays which formerly rough stuff, and just because they are stars have been \vere used by winning major league teams. They seem SHOOTING AND ALL CLEAN SFOBTS. getting away with it. Ty Cobb was fined ^25 and to have been forgotten or relegated by the order of *HB WORLD'S OLDEST AND BEST BASB BALL JODKNAL. suspended three days for pulling a stunt that should things. The hitting nowadays is not as strong as it have banned him for a month, without pay, yet maybe used to be in the old days, when the pitchers were ZOTTNDED APRIL, 1SS3 a captain or manager will be soaked just as much as just as good as they are today, and in many instances Cobb for arguing with the umpire over a decision that better.