Thesis 042813

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis

America’s Pastime: How Baseball Went from Hoboken to the World Series An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis Advisor Dr. Bruce Geelhoed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2020 Expected Date of Graduation July 2020 Abstract Baseball is known as “America’s Pastime.” Any sports aficionado can spout off facts about the National or American League based on who they support. It is much more difficult to talk about the early days of baseball. Baseball is one of the oldest sports in America, and the 1800s were especially crucial in creating and developing modern baseball. This paper looks at the first sixty years of baseball history, focusing especially on how the World Series came about in 1903 and was set as an annual event by 1905. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Carlos Rodriguez, a good personal friend, for loaning me his copy of Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary, which got me interested in this early period of baseball history. I would like to thank Dr. Bruce Geelhoed for being my advisor in this process. His work, enthusiasm, and advice has been helpful throughout this entire process. I would also like to thank Dr. Geri Strecker for providing me a strong list of sources that served as a starting point for my research. Her knowledge and guidance were immeasurably helpful. I would next like to thank my friends for encouraging the work I do and supporting me. They listen when I share things that excite me about the topic and encourage me to work better. Finally, I would like to thank my family for pushing me to do my best in everything I do, whether academic or extracurricular. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

A Historical Examination of the Institutional Exclusion of Women from Baseball Rebecca A

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2012 No Girls in the Clubhouse: A Historical Examination of the Institutional Exclusion of Women From Baseball Rebecca A. Gularte Scripps College Recommended Citation Gularte, Rebecca A., "No Girls in the Clubhouse: A Historical Examination of the Institutional Exclusion of Women From Baseball" (2012). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 86. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/86 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NO GIRLS IN THE CLUBHOUSE: A HISTORICAL EXAMINATION OF THE INSTITUTIONAL EXCLUSION OF WOMEN FROM BASEBALL By REBECCA A. GULARTE SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR BENSONSMITH PROFESSOR KIM APRIL 20, 2012 1 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my reader, Professor Bensonsmith. She helped me come up with a topic that was truly my own, and guided me through every step of the way. She once told me “during thesis, everybody cries”, and when it was my turn, she sat with me and reassured me that I would in fact be able to do it. I would also like to thank my family, who were always there to encourage me, and give me an extra push whenever I needed it. Finally, I would like to thank my friends, for being my library buddies and suffering along with me in the trenches these past months. -

A National Tradition

Baseball A National Tradition. by Phyllis McIntosh. “As American as baseball and apple pie” is a phrase Americans use to describe any ultimate symbol of life and culture in the United States. Baseball, long dubbed the national pastime, is such a symbol. It is first and foremost a beloved game played at some level in virtually every American town, on dusty sandlots and in gleaming billion-dollar stadiums. But it is also a cultural phenom- enon that has provided a host of colorful characters and cherished traditions. Most Americans can sing at least a few lines of the song “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Generations of children have collected baseball cards with players’ pictures and statistics, the most valuable of which are now worth several million dollars. More than any other sport, baseball has reflected the best and worst of American society. Today, it also mirrors the nation’s increasing diversity, as countries that have embraced America’s favorite sport now send some of their best players to compete in the “big leagues” in the United States. Baseball is played on a Baseball’s Origins: after hitting a ball with a stick. Imported diamond-shaped field, a to the New World, these games evolved configuration set by the rules Truth and Tall Tale. for the game that were into American baseball. established in 1845. In the early days of baseball, it seemed Just a few years ago, a researcher dis- fitting that the national pastime had origi- covered what is believed to be the first nated on home soil. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Baseball Cards

THE KNICKERBOCKER CLUB 0. THE KNICKERBOCKER CLUB - Story Preface 1. THE EARLY DAYS 2. THE KNICKERBOCKER CLUB 3. BASEBALL and the CIVIL WAR 4. FOR LOVE of the GAME 5. WOMEN PLAYERS in the 19TH CENTURY 6. THE COLOR LINE 7. EARLY BASEBALL PRINTS 8. BIRTH of TRADE CARDS 9. BIRTH of BASEBALL CARDS 10. A VALUABLE HOBBY The Knickerbocker Club played baseball at Hoboken's "Elysian Fields" on October 6, 1845. That game appears to be the first recorded by an American newspaper. This Currier & Ives lithograph, which is online via the Library of Congress, depicts the Elysian Fields. As the nineteenth century moved into its fourth decade, Alexander Cartwright wrote rules for the Knickerbockers, an amateur New York City baseball club. Those early rules (which were adopted on the 23rd of September, 1845) provide a bit of history (perhaps accurate, perhaps not) for the “Recently Invented Game of Base Ball.” For many years the games of Townball, Rounders and old Cat have been the sport of young boys. Recently, they have, in one form or another, been much enjoyed by gentlemen seeking wholesome American exercise. In 1845 Alexander Cartwright and other members of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York codified the unwritten rules of these boys games into one, and so made the game of Base Ball a sport worthy of attention by adults. We have little doubt but that this gentlemanly pastime will capture the interest and imagination of sportsman and spectator alike throughout this country. Within two weeks of adopting their rules, members of the Knickerbocker Club played an intra-squad game at the Elysian Fields (in Hoboken, New Jersey). -

Name of the Game: Do Statistics Confirm the Labels of Professional Baseball Eras?

NAME OF THE GAME: DO STATISTICS CONFIRM THE LABELS OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL ERAS? by Mitchell T. Woltring A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Leisure and Sport Management Middle Tennessee State University May 2013 Thesis Committee: Dr. Colby Jubenville Dr. Steven Estes ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not be where I am if not for support I have received from many important people. First and foremost, I would like thank my wife, Sarah Woltring, for believing in me and supporting me in an incalculable manner. I would like to thank my parents, Tom and Julie Woltring, for always supporting and encouraging me to make myself a better person. I would be remiss to not personally thank Dr. Colby Jubenville and the entire Department at Middle Tennessee State University. Without Dr. Jubenville convincing me that MTSU was the place where I needed to come in order to thrive, I would not be in the position I am now. Furthermore, thank you to Dr. Elroy Sullivan for helping me run and understand the statistical analyses. Without your help I would not have been able to undertake the study at hand. Last, but certainly not least, thank you to all my family and friends, which are far too many to name. You have all helped shape me into the person I am and have played an integral role in my life. ii ABSTRACT A game defined and measured by hitting and pitching performances, baseball exists as the most statistical of all sports (Albert, 2003, p. -

PHR Local Website Update 4-25-08

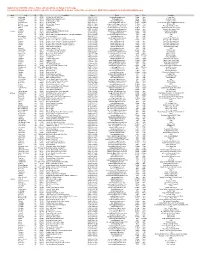

Updated as of 4/25/08 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Host or MLB PHR Headquarters at [email protected] State City ST Zip Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska Anchorage AK 99508 Mt View Boys & Girls Club (907) 297-5416 [email protected] 22-Apr 4pm Lions Park Anchorage AK 99516 Alaska Quakes Baseball Club (907) 344-2832 [email protected] 3-May Noon Kosinski Fields Cordova AK 99574 Cordova Little League (907) 424-3147 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Volunteer Park Delta Junction AK 99737 Delta Baseball (907) 895-9878 [email protected] 6-May 4:30pm Delta Junction City Park HS Baseball Field Eielson AK 99702 Eielson Youth Program (907) 377-1069 [email protected] 17-May 11am Eielson AFB Elmendorf AFB AK 99506 3 SVS/SVYY (907) 868-4781 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Elmendorf Air Force Base Nikiski AK 99635 NPRSA 907-776-8800x29 [email protected] 10-May 10am Nikiski North Star Elementary Seward AK 99664 Seward Parks & Rec (907) 224-4054 [email protected] 10-May 1pm Seward Little League Field Alabama Anniston AL 36201 Wellborn Baseball Softball for Youth (256) 283-0585 [email protected] 5-Apr 10am Wellborn Sportsplex Atmore AL 36052 Atmore Area YMCA (251) 368-9622 [email protected] 12-Apr 11am Atmore Area YMCA Atmore AL 36502 Atmore Babe Ruth Baseball/Atmore Cal Ripken Baseball (251) 368-4644 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Birmingham AL 35211 AG Gaston -

Baseball News Clippings

! BASEBALL I I I NEWS CLIPPINGS I I I I I I I I I I I I I BASE-BALL I FIRST SAME PLAYED IN ELYSIAN FIELDS. I HDBOKEN, N. JT JUNE ^9f }R4$.* I DERIVED FROM GREEKS. I Baseball had its antecedents In a,ball throw- Ing game In ancient Greece where a statue was ereoted to Aristonious for his proficiency in the game. The English , I were the first to invent a ball game in which runs were scored and the winner decided by the larger number of runs. Cricket might have been the national sport in the United States if Gen, Abner Doubleday had not Invented the game of I baseball. In spite of the above statement it is*said that I Cartwright was the Johnny Appleseed of baseball, During the Winter of 1845-1846 he drew up the first known set of rules, as we know baseball today. On June 19, 1846, at I Hoboken, he staged (and played in) a game between the Knicker- bockers and the New Y-ork team. It was the first. nine-inning game. It was the first game with organized sides of nine men each. It was the first game to have a box score. It was the I first time that baseball was played on a square with 90-feet between bases. Cartwright did all those things. I In 1842 the Knickerbocker Baseball Club was the first of its kind to organize in New Xbrk, For three years, the Knickerbockers played among themselves, but by 1845 they I had developed a club team and were ready to meet all comers. -

Lagrange College Baseball and Statistics Travel Seminar Draft Itinerary: May 17-26, 2020

LaGrange College Baseball and Statistics Travel Seminar Draft Itinerary: May 17-26, 2020 Day 1 Sunday, May 17, 2020 Depart Atlanta for Philadelphia Sample Flight Delta Flight DL 1494 Depart Atlanta (ATL) at 8:56 AM Arrive Philadelphia (PHL) at 10:59 AM 10:59 Arrive Philadelphia, 11:30 Meet Guide and Transfer to the Hotel 1:00 Group Lunch 2:30 - 4:30 Founding Fathers Tour of Philadelphia Experience the history of the United States on this guided, 2-hour, small-group walking tour around Philadelphia, the birthplace of freedom in America. See Independence Hall, where the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence (this tour does not enter Independence Hall). Snap a selfie with the iconic Liberty Bell. Learn about Pennsylvania’s founder, William Penn, and see where George Washington, the first President of the United States, lived. Then check out the galleries and eateries in Old City Philadelphia, America's most historic square mile 6:30 Group Welcome Dinner Day 2 Monday, May 18, 2020 Breakfast served in hotel 9:00 - 12:00 Cultural Experience Philadelphia Museum of Art 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway Philadelphia, PA 19130 Run up the Rocky Steps in front of the museum and take a picture with the Rocky Statue, then enter one of the largest and most renowned museums in the country. Find beauty, enchantment, and the unexpected among artistic and architectural achievements from the United States, Asia, Europe, and Latin America. 12:30 - 1:30 Group Lunch Philadelphia Cheesesteak Lunch Pat's King of Steaks or Geno's Steaks 2:00 - 3:30 Meeting or Cultural Activity Philadelphia Phillies 4:00 - 5:30 Citizens Bank Park Tour One Citizens Bank Way Philadelphia, PA 19148 Tour guests will be treated to a brief audio/visual presentation of Citizens Bank Park, followed by an up-close look at the ballpark. -

First Look at the Checklist

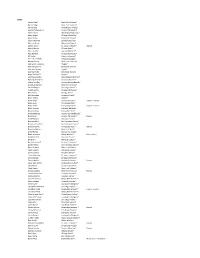

BASE Aaron Hicks New York Yankees® Aaron Judge New York Yankees® Aaron Nola Philadelphia Phillies® Adalberto Mondesi Kansas City Royals® Adam Eaton Washington Nationals® Adam Engel Chicago White Sox® Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® Adam Ottavino Colorado Rockies™ Addison Reed Minnesota Twins® Adolis Garcia St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie Albert Almora Chicago Cubs® Alex Colome Seattle Mariners™ Alex Gordon Kansas City Royals® All Smiles American League™ AL™ West Studs American League™ Always Sonny New York Yankees® Andrelton Simmons Angels® Andrew Cashner Baltimore Orioles® Andrew Heaney Angels® Andrew Miller Cleveland Indians® Angel Stadium™ Angels® Anthony Rendon Washington Nationals® Antonio Senzatela Colorado Rockies™ Archie Bradley Arizona Diamondbacks® Aroldis Chapman New York Yankees® Austin Hedges San Diego Padres™ Avisail Garcia Chicago White Sox® Ben Zobrist Chicago Cubs® Billy Hamilton Cincinnati Reds® Blake Parker Angels® Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ League Leaders Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ League Leaders Blake Treinen Oakland Athletics™ Boston's Boys Boston Red Sox® Brad Boxberger Arizona Diamondbacks® Brad Keller Kansas City Royals® Rookie Brad Peacock Houston Astros® Brandon Belt San Francisco Giants® Brandon Crawford San Francisco Giants® Brandon Lowe Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie Brandon Nimmo New York Mets® Brett Phillips kansas City Royals® Brian Anderson Miami Marlins® Future Stars Brian McCann Houston Astros® Bring It In National League™ Busch Stadium™ St. Louis Cardinals® Buster Posey San Francisco -

The History of Baseball the Rise of America and Its “National Game”

The History of Baseball The Rise of America and its “National Game” “Baseball, it is said, is only a game. True. And the Grand Canyon is only a hole in Arizona.” – George Will History 389-007 Dr. Ryan Swanson Contact: [email protected] Office hours: Monday 1:30-3pm, by appt. Robinson B 377D Baseball. America’s National Pastime. The thinking man’s and thinking woman’s sport. A rite of spring and ritual of fall. A game that explains the nation, or at least that’s what some have contended. ―Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America,‖ argued French historian Jacques Barzan, ―had better learn Baseball.‖ The game is at once simple, yet complex. And so is the interpretation of its history. In this course we will examine the development of the game of baseball as means of better understanding the United States. Baseball evidences many of the contradictions and conflicts inherent in American history—urban v. rural, capital v. labor, progress v. nostalgia, the ideals of the Bill of Rights v. the realities of racial segregation, to name a few. This is not a course where we will engage in baseball trivia, but rather a history course that uses baseball as its lens. Course Objectives 1. Analyze baseball’s rich primary resources 2. Understand the basic chronology of baseball history 3. Critique 3 secondary works 4. Interpret the rise and fall of baseball’s racial segregation 5. Write a thesis-driven, argumentative historical paper Structure The course will utilize a combination of lectures and discussion sessions.