Visto En La Casa De Las Américas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Una Mirada a La Inmigración Española De 1939-40 En Santo Domingo

Una mirada a la inmigración española de 1939-40 en Santo Domingo Disertaciones presentadas en la Universidad APEC Semanas de España en la República Dominicana 2015 Santo Domingo, R.D. Octubre 2016 Una mirada a la inmigración española de 1939-40 en Santo Domingo : disertaciones presentadas en la Universidad APEC : Semanas de España en la República Dominicana 2015 / José del Castillo Pichardo ...[et al.] ; Jaime Lacadena, introducción. – Santo Domingo : Universidad APEC, 2016 168 p. : il. ISBN: 978-9945-423-39-6 1. Emigración - Española 2. Inmigración - República Dominicana 2. España - Historia - Guerra civil, 1936-1939 3. Exilio - España 4. República Dominicana - Influencias españolas 3. Arte dominicano - Influencias españolas 5. España - Vida intelectual - República Dominicana. I. Castillo Pichardo, José del. II. González Tejera, Natalia. III. Vega, Bernardo. IV. Gil Fiallo, Laura. V. Mateo, Andrés L. VI. Céspedes, Diógenes. VII. Lacadena, Jaime, introd. 304.8 I57e CE/UNAPEC Título de la obra: Una mirada a la inmigración española de 1939-40 en Santo Domingo Disertaciones presentadas en la Universidad APEC Semanas de España en la República Dominicana 2015 Primera edición: Octubre 2016 Gestión editorial: Oficina de Publicaciones Vicerrectoría de Investigación, Innovación y Relaciones Internacionales Composición, diagramación y diseño de cubierta: Departamento de Comunicación y Mercadeo Institucional Impresión: Editora Búho ISBN: 978-9945-423-39-6 Impreso en República Dominicana Printed in Dominican Republic JUNTA DE DIRECTORES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD APEC Lic. Opinio Álvarez Betancourt Presidente Lic. Fernando Langa Ferreira Vicepresidente Lic. Pilar Haché Tesorera Dra. Cristina Aguiar Secretaria Lic. Álvaro Sousa Sevilla Miembro Lic. Peter A. Croes Miembro Lic. Isabel Morillo Miembro Lic. -

NEWSLETTER Information Exchange in the Caribbean July 2012 MAC AGM 2012

ISSUE 8 NEWSLETTER Information Exchange in the Caribbean July 2012 MAC AGM 2012 Plans are moving ahead for the 2012 MAC AGM which is to be held in Trinidad, October 21st-24th. For further information please regularly visit the MAC website. Over the last 6 months whilst compiling articles for the newsletter one positive thing that has struck the Secretariat is the increase in the promotion Inside This Issue of information exchange in the Caribbean region. The newsletter has covered a range of conferences occurring this year throughout the Caribbean and 2. Caribbean: Crossroads of several new publications on curatorship in the Caribbean will have been the World Exhibition released by the end of 2012. 3. World Heritage Inscription Ceremony in Barbados Museums and museum staff should make the most of these conferences and 4. Zoology Inspired Art see them not only as a forum to learn about new practices but also as a way 5. 2012 MAC AGM to meet colleagues, not necessarily just in the field of museum work but also 6. New Book Released in many other disciplines. In the present financial situation the world finds ´&XUDWLQJLQWKH&DULEEHDQµ 7. Sint Marteen National itself, it may sound odd to be promoting attendance at conferences and Heritage Foundation buying books but museums must promote continued professional 8. ICOM Advisory Committee development of their staff - if not they will stagnate and the museum will Meeting suffer. 9. Membership Form 10. Association of Caribbean MAC is of course aware that the financial constraints facing many museums at Historians Conference present may limit the physical attendance at conferences. -

Insights from the Field

Insights From the Field UNDERSTANDING GEOGRAPHY, CULTURE, AND SERVICE Paul D. Coverdell worldwise schools Paul D. Coverdell worldwise schools This guide contains materials that were written by educators and others.The views presented here are not official opinions of the United States government or of the Peace Corps. Contents Introduction The Purpose of this Curriculum............................................................ 5 About the Peace Corps...........................................................................6 Coverdell World Wise Schools................................................................ 7 A Standards-Based Approach.................................................................. 8 Content Standards Addressed in this Guide.............................................13 Unit One: Geography: It’s More Than Just a Place Introduction:The Unit at a Glance.........................................................15 Module One:Where We Live Influences How We Live......................... 20 Module Two: Understanding Demographics........................................... 37 Module Three: Beyond Demographics....................................................43 Module Four: Life in a Hurricane Zone................................................ 48 Culminating Performance Task...............................................................59 Unit Two: Culture: It’s More Than Meets the Eye Introduction:The Unit at a Glance.........................................................62 Module One: Understanding Culture.................................................... -

View Exhibition Brochure

1 Renée Cox (Jamaica, 1960; lives & works in New York) “Redcoat,” from Queen Nanny of the Maroons series, 2004 Color digital inket print on watercolor paper, AP 1, 76 x 44 in. (193 x 111.8 cm) Courtesy of the artist Caribbean: Crossroads of the World, organized This exhibition is organized into six themes by El Museo del Barrio in collaboration with the that consider the objects from various cultural, Queens Museum of Art and The Studio Museum in geographic, historical and visual standpoints: Harlem, explores the complexity of the Caribbean Shades of History, Land of the Outlaw, Patriot region, from the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) to Acts, Counterpoints, Kingdoms of this World and the present. The culmination of nearly a decade Fluid Motions. of collaborative research and scholarship, this exhibition gathers objects that highlight more than At The Studio Museum in Harlem, Shades of two hundred years of history, art and visual culture History explores how artists have perceived from the Caribbean basin and its diaspora. the significance of race and its relevance to the social development, history and culture of the Caribbean: Crossroads engages the rich history of Caribbean, beginning with the pivotal Haitian the Caribbean and its transatlantic cultures. The Revolution. Land of the Outlaw features works broad range of themes examined in this multi- of art that examine dual perceptions of the venue project draws attention to diverse views Caribbean—as both a utopic place of pleasure and of the contemporary Caribbean, and sheds new a land of lawlessness—and investigate historical light on the encounters and exchanges among and contemporary interpretations of the “outlaw.” the countries and territories comprising the New World. -

Tercera Parte Oviedo

SÍNTESIS DE LOS TEXTOS Version en inglés Véronique Viala de Gallardo WHATISTHE PAINTING OF HISTORY? THE ROOTS of the word “history” re- clouds. The work of French-Guadelou- fer to the quest of information, of truth, pean artist Guillon-Lethière, showing to the telling, the analysis and the inter- Haitian generals Pétion and Dessalines pretation of events, to a history that is sealing their union under the look of the course of life and fate as well as the God and trampling the chains of slavery, discipline that studies them. The means is an example of this style. Eugène De- of expression have become more nu- lacroix, the last great European histori- merous over the centuries, images have cal painter, was able to breathe a mythi- come to reinforce writing. Photography cal dimension to political and social rea- changed the course of representative lities. art, imposing its testimony, and taking The advent of photography and the away from the painting of history one first photoreports were to change Wes- of its raisons d'être, the visual account tern painting of history. Figurative com- of facts. As for Ramón Oviedo, he has memoration was to survive in some never stopped reinterpreting and rein- compositions during the XXth century, OVIEDO. Extinction of a race. venting history. about World War I, for example, going Mythification was an integral part of back to outmoded aesthetic forms. As traditional rhetoric and painting of his- for painting under the Western dicta- tory. Both the classical and the romantic torships, it was a mere propaganda ve- eras were times of tributes and apolo- hicle of poor pictorial quality. -

Visual Art As a Window for Studying the Caribbean Compiled and Introduced by Peter B

Visual Art as a Window for Studying the Caribbean Compiled and introduced by Peter B. Jordens Curaçao: August 26, 2012 The present document is a compilation of 20 reviews and 36 images1 of the visual-art exhiBition Caribbean: Crossroads of the World that is Being held Between June 12, 2012 and January 6, 2013 at three cooperating museums in New York City, USA. The remarkaBle fact that Crossroads has (to date) merited no fewer than 20 fairly formal art reviews in various US newspapers and on art weBlogs can Be explained By the terms of praise in which the reviews descriBe the exhiBition: “likely the most expansive art event of the summer (p. 20 of this compilation), the summer’s BlockBuster exhiBition (p. 21), the big art event of the summer in New York (p. 15), immense (p. 34), Big, varied (p. 21), diverse (p. 10), comprehensive (p. 20), amBitious (pp. 19, 21, 22, 33, 34), impressive (p. 21), remarkaBle (p. 21), not one to miss (p. 30), wholly different and very rewarding (p. 33), satisfying (pp. 21, 33), visual feast (p. 25), Bonanza (p. 25), rare triumph (p. 21), significant (p. 13), unprecedented (p. 10), groundbreaking (pp. 13, 23), a game changer (p. 13), a landmark exhiBition (p. 13), will define all other suBsequent CariBBean surveys for years to come (p. 22).” Crossroads is the most recent tangiBle expression of an increase in interest in and recognition of CariBBean art in the CariBBean diaspora, in particular the USA and to less extent Western Europe. This increase is likely the confluence of such factors as: (1) the consolidation of CariBBean immigrant communities in North America and Europe, (2) the creative originality of artists of CariBBean heritage, (3) these artists’ greater moBility and presence in the diaspora in the context of gloBalization, especially transnational migration, travel and information flows,2 and (4) the politics of multiculturalism and of postcolonial studies. -

Catálogo Fondo Raúl Anguiano

José Raúl Anguiano Valadez (1915-2006) Autorretrato Pintor, muralista y grabador, nacido en el estado de Jalisco en el año de 1915. Exponente del muralismo mexicano; su trabajo en este género artístico pertenece a la segunda generación de muralistas al lado de Jorge González Camarena, Juan O’Gorman y Federico Cantú Garza. En 1934 llegó a la ciudad de México y se unió a la Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios. En 1938 fue miembro fundador del Taller de la Gráfica Popular, más tarde de la Escuela de Pintura y Escultura La Esmeralda y en 1952 del Salón de la Plástica Mexicana. La escuela que siguió fue la clásica académica, manifestando su inclinación por el dibujo preciso, fuerte, riguroso y concreto. Después de un viaje al sitio arqueológico maya de Bonampak (Ocosingo, Chiapas) en 1949, surgió en él la pasión por la temática indígena y creó el estilo conocido como indigenista, el cual fue una constante en su carrera y lo definiría dentro de la plástica mexicana. Murió a la edad de 91 años en la capital de la república mexicana, dejando un invaluable legado como muralista, pintor, litógrafo y creador de innumerables obras de los diferentes géneros del campo de las artes. Críticos de arte han comentado acerca de la obra del Mtro. Anguiano:1 La vida del pueblo, es, ciertamente, la realidad de mayor volumen en la obra de Anguiano; allí el drama percibido y expresado por el artista, ya sea en el trabajo sinfín que el hombre lleva a cuestas, en los vicios, a veces tratados con suma gracia en las fiestas y entretenimientos y, sobre todo, en la resignación o el estoicismo con que pinta a la mujer mexicana. -

Kobro Ing.Pdf

KATARZYNA KOBRO & WŁADYSŁAW STRZE MIŃ KOBRO STRZEAVANT-GARDE PROTOTYPES ŃSKI atarzyna Kobro (1898–1951) and Władysław Strzemiński (1893–1952) are among the silent protagonists of the Eu- ropean avant-gardes, to which they contributed by both fostering and questioning the legacy of modernism with a plastic and theoretical oeuvre that was as fertile as it was Kcomplex. Dedicated to experimentation on pure forms—Kobro funda- mentally in sculpture and Strzemiński in painting—and closely related to international artistic movements like the Bauhaus, neoplasticism and constructivism, their work is pivotal for an understanding of abstract art in the Central Europe of the first decades of the twentieth century. The Museo Reina Sofía presents a retrospective on their work made up of drawings, paintings, collages, sculptures and designs ranging from the typographical arrangement of a poem to furnishing concepts or the projection of architectural spaces. With exhibits dating from the early 1920s to the late 1940s, the show functions as an exegesis of their heterogeneous production through a description of the artistic transi- tions that marked their careers. Clearly influenced at first by such great avant-garde figureheads as Tatlin, Rodchenko and Malevich, their work moves on to their unist creations, their great contribution. Unism was abandoned with the arrival of the economic crisis, and after a period dedicated to an art they classed as “recreational” and, simultaneously, to the practice of functionalism, Kobro and Strzemiński took different paths. At the end of the Second World War, she made sculptures of nudes close to cubism, while he started to sketch out a realist theory ver- tebrated by works where afterimages live side by side with abstraction. -

Afro-Latin American Art

10 Afro-Latin American Art Alejandro de la Fuente1 It is a remarkable moment, barely perceptible, tucked at the edge of the image. Titled “Mercado de Escravos,” the 1835 Johann Moritz Rugendas (1802–58) lithograph depicts a group of African slaves who wait to be purchased, while some potential buyers walk around and a notary or scribe appears ready to make use of the only visible desk (see Figure 10.1). In the background, a Catholic Church coexists harmoniously with the market and overlooks a bay and a vessel, perhaps the same ship that brought those Africans from across the Atlantic. While they wait, most of the slaves socialize, sitting around a fire. Others stand up, awaiting their fate, between resignation and defiance. One slave, however, is doing something different: he is drawing on a wall, an action that elicits the attention of several of his fellow slaves (see Figure 10.1A). What was this person drawing on the wall? What materials was he using? Who was his intended audience? Did these drawing partake of the graphic communication systems developed by some population groups in the African continent? Was he drawing one of the cosmograms used by the Bantu people from Central Africa to communicate with the ancestors and the divine? (Thompson 1981; Martínez-Ruiz 2012). Was he leaving a message for other Africans who might find themselves in the same place at 1 I gratefully acknowledge the comments, suggestions, and bibliographic references that I received from Paulina Alberto, George Reid Andrews, David Bindman, Raúl Cristancho Álvarez, Thomas Cummins, Lea Geler, María de Lourdes Ghidoli, Bárbaro Martínez- Ruiz, and Doris Sommer. -

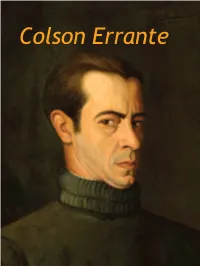

Colson Errante Colson Errante 1 H

Colson Errante Colson Errante 1 H NY P B M LH CM. Colson Errante H SD Colson Errante 2 3 C Colson Errante Colson Errante 4 5 Colson Errante Colson Errante 6 20 de noviembre de 2008 Sala de Exposiciones Temporales Museo Bellapart H NY P Índice B M Un sueño hecho realidad 6 Jaime Colson considera JUAN JOSE BELLAPART que el arte contemporáneo está barbarizado 136 POR MARÍA UGARTE Colson: Fuerza e instinto creador 12 PAULA GÓMEZ JORGE Los pasos de Colson 1918-1958 144 Jaime ColsonLH en el Museo Bellapart 15 Cronología 1901-2008 146 POR RICARDO RAMÓN JARNE Período de aprendizaje en España 1918-1924 17 CM. Perfil Biográfico de Autores 154 Colson Errante Las vanguardias en París y abrazo al cubismo 1924-1928 21 Colson Errante H El triunfo del Neohumanismo 1929-1934SD 28 8 9 México 1934-1938 34 Catálogo de obras 156 El periplo trashumante 1938 -1939 46 Barcelona 1939-1949 56 Bibliografía 170 Pintura de subsistencia y religiosa. La catarsis 56 Vuelta a París 1949 79 República Dominicana 1950-1975 80 Cubismo y negritud 87 C Jaime Colson: Desde el Caribe a la Modernidad 106 POR ABELARDO G. MENA CHICURI Las Pasiones de Colson 108 POR MARIANNE DE TOLENTINO La Pasión por el Maestro 108 La Pasión y el Cuerpo 111 La Catarsis 115 Raza y Antillanismo 117 Importancia de la Religión 118 Impulsos creativos y Energías 122 Amistad y Sentimientos 126 El Pintor Trashumante 130 El Gran Sufrimiento Final 133 Imagen de portada Autorretrato, 1925 Óleo sobre madera 48.5 x 40.5 cm. -

I PAINT MY REALITY Surrealism in Latin America Through Spring 2021

I PAINT MY REALITY Surrealism in Latin America Through Spring 2021 The avant-garde Surrealist movement emerged in France in the wake of World War I and spread globally as artists and art works traveled, and ideas circulated through art journals and mass media. Dreams, psychoanalysis, automatism (creating without conscious thought), collage, assemblage and chance were among the methods the Surrealists used to tap into the unconscious mind and stimulate the imagination. The European Surrealists embraced their Latin American colleagues, who nevertheless expressed ambivalence about the movement. Mexican artist Frida Kahlo famously refuted being labeled as a Surrealist, stating that she never painted dreams, instead asserting, “I painted my own reality,” while Uruguayan Joaquin Torres-Garcia advocated for a modern art that was not beholden to European modern art. Latin America’s complex history, magical landscapes, indigenous cultures, archeological sites, mythologies, migrations, and European and African religious traditions shaped these artists’ reality. The rise of fascism in Europe in the 1930s as well as the Spanish Civil War and World War II shifted the focus of Surrealism to the United States and Latin America, where many of the European artists sought refuge. These artists’ proximity to each other promoted friendships that were especially fruitful during this period and in the post-war years. While many of the exiled European artists who lived in the United States during the war returned home afterwards, those in Latin America and in Mexico in particular, tended to remain there for the rest of their lives. This exhibition is drawn exclusively from NSU Art Museum’s Latin American collection, including promised gifts from Fort Lauderdale collectors Stanley and Pearl Goodman. -

Mario Carreño

(Des)Aparecen los ducos de MARIO CARREÑO Por José Ramón Alonso Lorea. EECC2003 Edición EstudiosCulturales2003.es Miami, septiembre de 2016 1 Según reconocía Mario Carreño en sus memorias (1991), “nunca supe qué se hicieron esos paneles que pinté al duco1 a pesar de que estuvieron expuestos en París, Moscú y el Museo de Arte Moderno de 2 Nueva York, desaparecieron misteriosamente”. Hoy, ya no es así. La mayoría de estos ducos, seis décadas después de pintados y expuestos (algunos no fueron exhibidos, pues fueron considerados ensayos o experimentos), han ido re-apareciendo a través de las casas de subasta de arte, principalmente. Las obras han logrado importantes cotizaciones, lo que a su vez ha estimulado la aparición de otras antológicas tablas que se creían irremediablemente perdidas o, en el mejor de los casos, en paradero desconocido. En México, en 1936, y “bajo la tutela artística” del pintor dominicano Jaime Colson, Mario Carreño había iniciado “sus primeras investigaciones con las lacas llamadas ducos”. Pero durante su viaje por Europa había desistido de este material innovador ante el tradicionalismo pictórico del óleo.3 Pero con la llegada a Cuba, en 1943, del pintor mexicano David Alfaro Siqueiros, Carreño revaloriza la técnica del duco. Ante la imposibilidad de lograr un espacio público donde dejar su impronta muralista, Siqueiros aceptó el encargo original de la familia Carreño-Gómez Mena de hacer un Mario Carreño delante del duco Fuego en el batey. Foto firmada en el cuadro de caballete, lo cual fue hábilmente transformado por él en un inferior derecho por Julio Berestein, mural interior donde utilizó la técnica del duco -piroxilina del tipo de La Habana, [agosto-noviembre] de la que se utiliza para pintar coches- con pistola pulverizadora, sobre 1943.