AWEJ Vol5 No 1 March 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Basic Challenges and Strategies in Teaching Translation to Chemistry Majors Iazyka (Pp

Training, Language and Culture doi: 10.29366/2018tlc.2.3.4 Volume 2 Issue 3, 2018 rudn.tlcjournal.org Some basic challenges and strategies in teaching translation to Chemistry majors iazyka (pp. 48-56). Moscow: Agraf. Svetovidova, I. V. (2000). Perenos znacheniia i ego ontologiia by Elena E. Aksenova and Svetlana N. Orlova Schwanke, M. (1991). Maschinelle Übersetzung: v angliiskom i russkom iazykakh [Transfer of meaning Klärungsversuch eines unklaren Begriffs [Machine and its ontology in English and Russian]. Moscow: Elena E. Aksenova Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO University) [email protected] translation: Clarifying the unclear term]. In Lomonosov Moscow State University. Maschinelle Übersetzung (pp. 47-67). Berlin, Toury, G. (2012). Descriptive translation studies and beyond: Svetlana N. Orlova Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University) [email protected] Heidelberg: Springer. Revised edition (Vol. 100). John Benjamins Publishing. Published in Training, Language and Culture Vol 2 Issue 3 (2018) pp. 71-85 doi: 10.29366/2018tlc.2.3.5 Schweitzer, A. D. (1988). Teoriia perevoda: Status, problemy, Venuti, L. (2017). The translator’s invisibility: A history of Recommended citation format: Aksenova, E. E., & Orlova, S. N. (2018). Some basic challenges and strategies in aspekty [Theory of translation: Status, issues, aspects]. translation. Routledge. teaching translation to Chemistry majors. Training, Language and Culture, 2(3), 71-85. doi: Moscow: Nauka. Vinay, J. P., & Darbelnet, J. (1958). Stylistique comparée de Shaitanov, I. (2009). Perevodim li Pushkin? Perevod kak l’anglais et du français [Stylistic comparison of English 10.29366/2018tlc.2.3.5 komparativnaia problema [Is Pushkin translatable? and French]. Paris and Montreal: Didier/Beauchemin. -

6 the Affront Of

6 The Affront of UntranslatabilityDavid GramlingThe Affront of Untranslatability Ten Scenarios David Gramling I too am not a bit tamed, I too am untranslatable. —(Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself”) Non que je cultive l’intraduisible. —(Jacques Derrida, Le Monolinguisme de l’autre: 100) Untranslatability is, already on the face of it, a less-than-amicable dis- course, prone to offence and to disturbing interdisciplinary peace. Now a century and a half since Whitman’s penning of “Song of Myself,” so- called Untranslatables continue to “sound [their] barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world,” whether or not they are appreciated when and where they do so (Whitman [1855] 2016: 183). This chapter is devoted not to repairing the word untranslatability’s accumulated impertinences, but to canvassing a range of typical scenarios that, when viewed collectively, might account for the social effrontery inherent in untranslatability as a concept, a charge or a gesture. This is thus not an apologetic exploration, nor one that sets out to delimit the phenomenon of untranslatability as such—as so many other thoughtful investigations in this book do—but is rather an attempt to understand the complex, even chaotic illocutionary force that calling something “untranslatable” routinely unleashes in vari- ous scholarly and everyday conversations. To the extent that the reader agrees with the notion that effrontery is somehow immanent in the word untranslatable, and that a variety of typical scenarios of affront collude with one another to intensify for the word an arch and casuistic aura, we may then consider whether the concept of untranslatability is—despite itself—still capable of holding water in scholarly work, cultural politics and indeed activism, and whether any modest adjustments might miti- gate its performative excesses thus far. -

Translation Loss in Translation of the Glorious Quran, with Special Reference to Verbal Similarity

Translation Loss in Translation of the Glorious Quran, with Special Reference to Verbal Similarity Batoul Ahmed Omer Translation Loss in Translation of the Glorious Quran, with Special Reference to Verbal Similarity Batoul Ahmed Omer Abstract The process of translation is highly delicate and extremely difficult task to undertake when it deals with the translation of the Quran which, of course, transforms the Quran as the WORD of Allah into Arabic to the speech of a human being in another language. Translations of the Quran into all languages are indispensable to communicate the Divine message to Non-Arabic Muslims as well as Non-Muslims around the world. Nowadays, numerous translations are available for non-Arabic speakers. Many English translations have been widely criticized for their inability to capture the intended meaning of Quranic words and expressions. These translations proved the inimitability of the Qur'anic discourse that employs extensive and complex syntactical and rhetoric features and that linguistically the principle of absolute untranslatability applies to the Quran. Consequently, partial or complete grammatical and semantic losses are encountered in translation due to the lack of some of these features in English. These translation losses is particularly apparent in translation of verbal similarity in the Quranic verses, as an abundant phenomenon in the Quran, in the form of over-, under-, or mistranslation of a source text (ST). This study attempted to investigate these translation losses in the translation of the Holy Quran focusing on verbal similarity as an impressive way of expression and a rhetorical figure widely used in the Quran. Qualitative descriptive approach was adopted to analyze the data extracted from among the best known translations of the Quran, (Abdallah Yusuf Ali 1973) Translation of the Meaning of the Glorious Quran into English and Pickthall’s (1930) The Meaning of the Holy Quran and Arthur John Arberry (1905-1969) The Koran Interpreted. -

The Accuracy of the English-Indonesian Translation of Cultural Terms in Hosseini’S

THE ACCURACY OF THE ENGLISH-INDONESIAN TRANSLATION OF CULTURAL TERMS IN HOSSEINI’S A THOUSAND SPLENDID SUNS a Final Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Department by Dinda Anjasmara Puspita 2211416027 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND ARTS UNIVERSITAS NEGERI SEMARANG 2020 ii iii MOTTO AND DEDICATION ”It is difficult to be patient but to waste the rewards for patience is worse.” (Abu Bakr as-Siddiq RA) This final project is dedicated to: - My dearest parents - My beloved family - All of my friends iv ACKWOLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to Allah SWT for all His favor and guidance. Without His continuously help and mercy, this final project will not be complete. Peace and salutation be upon to the greatest prophet Muhammad SAW who had brought us from the darkness to the lightness era. I would like to express my sincere thanks to my advisor, Dr. Rudi Hartono, M.Pd. for giving me continuous guidance, suggestions and encouragement in finishing this final project. My special thank also addressed to all lecturers and staff of English Department of Universitas Negeri Semarang who have given me great knowledge, motivation and guidance during the years of my study at Universitas Negeri Semarang. I dedicate my sincerest and deepest thanks to my beloved Father (Yatno Yuwono) and mother (Intra Miarsih), my sisters (Ajeng Tirana Puspita, and Antradiva Oktaviola Puspita), who always support me with great love, attention, and continuous prayer. Special thanks goes to the all expert raters, Mrs. -

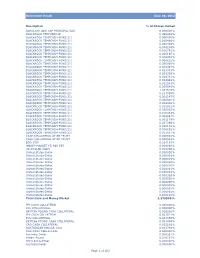

Retirement Funds June 30, 2012 Description % of Shares Owned

Retirement Funds June 30, 2012 Description % of Shares Owned BARCLAYS LOW CAP PRINCIPAL CAS 0.000000% BLACKROCK FEDFUND(30) 0.440244% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000000% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000486% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000485% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.008246% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.006791% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.005165% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.006043% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.004035% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.035990% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.020497% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.023343% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.008326% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000781% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.004848% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.022593% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000646% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 1.307615% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.214356% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.001147% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.024810% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.009406% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.018922% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.030062% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.010464% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.004697% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.001179% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.007266% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.000112% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.008062% BLACKROCK TEMPCASH-FUND(21) 0.011657% CASH COLLATERAL AT BR TRUST 0.000001% CASH COLLATERAL AT BR TRUST 0.000584% EOD STIF 0.024153% MONEY MARKET FD FOR EBT 0.000000% US DOLLAR CASH 0.008786% United States-Dollar 0.000000% United States-Dollar 0.000003% United States-Dollar 0.000019% United States-Dollar 0.000003% United States-Dollar -

A Dictionary of Translation and Interpreting

1 A DICTIONARY OF TRANSLATION AND INTERPRETING John Laver and Ian Mason 1 2 This dictionary began life as part of a much larger project: The Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Speech and Language (General Editors John Laver and Ron Asher), involving nearly 40 authors and covering all fields in any way related to speech or language. The project, which from conception to completion lasted some 25 years, was finally delivered to the publisher in 2013. A contract had been signed but unfortunately, during a period of ill health of editor-in- chief John Laver, the publisher withdrew from the contract and copyright reverted to each individual contributor. Translation Studies does not lack encyclopaedic information. Dictionaries, encyclopaedias, handbooks and readers abound, offering full coverage of the field. Nevertheless, it did seem that it would be a pity that the vast array of scholarship that went into The Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Speech and Language should come to nought. Consequently, we offer this small sub-part of the entire project as a free-to-use online resource in the hope that it will prove to be of some use, at least to undergraduate and postgraduate students of translation studies – and perhaps to others too. Each entry consists of a headword, followed by a grammatical categoriser and then a first sentence that is a definition of the headword. Entries are of variable length but an attempt is made to cover all areas of Translation Studies. At the end of many entries, cross-references (in SMALL CAPITALS) direct the reader to other, related entries. Clicking on these cross- references (highlight them and then use Control and right click) sends the reader directly to the corresponding headword. -

And Cross-Lingual Paraphrased Text Reuse and Extrinsic Plagiarism Detection

Mono- and Cross-Lingual Paraphrased Text Reuse and Extrinsic Plagiarism Detection Muhammad Sharjeel School of Computing and Communications, Lancaster University Supervisors: Dr. Paul Rayson Dr. Rao Muhammad Adeel Nawab Lancaster University, COMSATS University Islamabad, Lancaster, United Kingdom Lahore Campus, Pakistan [email protected] [email protected] A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science June 23, 2020 This thesis is dedicated to my mother, and my late father. Acknowledgements In the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful First and foremost, I thank the Almighty Allah (SWT), the ultimate source of all knowledge and wisdom in this world, for His countless blessings on me. Regarding my dissertation, I would like to express my sincere gratitude towards my thesis supervisors, Dr. Paul Rayson and Dr. Rao Muhammad Adeel Nawab. And I wish to “reuse” this sentence in so many ways, to show how grateful I am for their guidance, continuous motivation, and outstanding support that formed an endless “corpus” of wisdom that will be with me, always! I greatly admire Dr. Paul Rayson for being a kind, accessible, and an amiable supervisor. I am indebted to Dr. Rao Muhammad Adeel Nawab for mentoring my research for the past several years and helping me to develop a strong background in Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning. A thanks also goes to all the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback that has led to significant improvements in my PhD study. A heartfelt thanks goes to my parents! Words cannot express my feelings, espe- cially towards my mother. -

Translating Humor: a Comparative Analysis of Three

TRANSLATING HUMOR: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THREE TRANSLATIONS OF THREE MEN IN A BOAT HARİKA KARAVİN BOĞAZİÇİ UNIVERSITY 2015 TRANSLATING HUMOR: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THREE TRANSLATIONS OF THREE MEN IN A BOAT Thesis submitted to the Institute for Graduate Studies in Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Translation Studies by Harika Karavin B U 2015 ABSTRACT Translating Humor: A Comparative Analysis of Three Translations of Three Men in a Boat When academic studies on translating humor are examined in Turkey, there are not sufficient sources or data providing enough space for the discussion of the issue. It is also observed that most of the available studies focus on the linguistic and cultural problems observed in the transference of humorous elements in audio-visual texts and deal only with the translation of the specific humorous elements (e.g. wordplay) in terms of verbal humor. As a conclusion, it has been found out that there does not exist a comprehensive study in the target system that provides detailed information on the translation of verbal humor and the problems to be observed in the translation process. Since the translation strategies display differences in relation to the type of humorous device that texts include, studies focusing on the translation of different humorous devices are required. For this purpose, a descriptive comparison of the three l f J m K. J m ’ f m u l Three Men in a Boat including different humorous devices has been carried out. In the comparisons, the g x ’ lu c h u c x ’ hum u ff c h b analyzed in a descriptive manner and an objective translation criticism has been presented. -

Lexical Gaps and Untranslatability in Translation

================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 20:5 May 2020 ============================================================= Lexical Gaps and Untranslatability in Translation Prof. Rajendran Sankaravelayuthan Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetam University Coimbatore 641 112 [email protected] ================================================================== 1. Introduction Linguists consider the word as a crucial unit in their description of language. While doing so they mostly focus on those words that are recognized as part of the vocabulary of a language. Sometimes it is relevant to consider the words that are not part of the vocabulary. They can be referred to as non-existing words. In lexical semantics, it is customary to talk about lexical gaps instead of referring to non-existing words. The non-existing words are indications of “gaps” or “holes” in the lexicon of the language that could be filled. Lexical gaps are also known as lexical lacunae. The vocabulary of all the languages, including English and Tamil, shows lexical gaps. For example, the English noun horse as a hypernym incorporates its denotation both stallion (male horse) and mare (female horse). However, there is no such hypernym in the case of cows and bulls, which subsumes both cow and bull in denotation. The absence of such a hypernym is called a lexical gap. Lyons (1977, pp. 301-305) addresses lexical gaps from a structuralist perspective. He defines lexical gaps as slots in a patterning. Wang (1989) defines lexical gaps as empty linguistic symbols and Fan (1989) defines them as empty spaces in a lexeme cluster. Rajendran (2001) defines lexical gap as a vacuum in the vocabulary structure of a language. -

Untranslatability and Readability

John Cayley Brown University UNTRANSLATABILITY AND READABILITY Abstract: Rather than as a function or inevitable consequence of conventional translation practices (of, for example, some attempt on the ‘untranslatable’ poem), or as the literary maker's right to refuse the application of such practices, untranslatability is proposed as a special case of unreadability, where the latter is taken to be entailed by all embodiments of language-as-such in particular natural languages or linguistic forms. A thought experiment is described within which mutual unreadability is inscribed in the form of separate monolingual discussions on the same special subject. The discussion is complicated by the proposal that the subject of discussion - in both thought experiment and essay - is that of an actual, Chinese, 'unreadable book,' the artist Xu Bing's (1955- ) Book from the Sky. Keywords: translation untranslatability readability and unreadability philosophy of language literary conceptualism art and language n “On language as such and on the language of man” Walter Benjamin grounds a crucial understanding of translation on the commensurability of separately instituted I human communities. He evokes what he calls an “evolved language” abstracted from the totality of a particular human community’s linguistic practices. “Translation attains its full meaning in the realization that every evolved language can be considered as a translation of all the others.” (Benjamin 1997, 117) Benjamin wrote in German, a Cayley, John. “Untranslatability and Readability.“ Critical Multilingualism Studies 3:1 (2015): pp. 70-89. ISSN 2325-2871. Cayley Untranslatability and Readability language of which I know very little. I read his German texts only through existing English translations. -

Untranslatability and Philosophy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham INVISIBLE UNTRANSLATABILITY AND PHILOSOPHY KATHRYN BATCHELOR The subtitle of the Vocabulaire européen des philosophies, ‘dictionnaire des intraduisibles’, links the publication to the issue of untranslatability that has accompanied discussions of translation throughout history; Andrew Chesterman even goes so far as to identify untranslatability as one of the five ‘supermemes’ of translation.1 This problematization of the very possibility of translation, and the issues that it pushes to the fore, becomes particularly acute when considered in conjunction with another issue on which scholarly attention has recently focussed, namely that of translation invisibility. This latter notion – associated primarily with the writings of Lawrence Venuti – refers to the general tendency to overlook the fact of a text’s translation; to read a text as if it were the original, and to ignore the inevitable differences that are introduced through the act of translation. In this paper, I shall outline recent thinking on the issue of untranslatability as it relates specifically to philosophy, examining the implications of the translation of untranslatables, particularly in terms of how the relationship between originals and translations is conceived. I shall also assess the extent to which invisibility is truly an issue in relation to translations of philosophical texts, and explore the inevitable dissonance that arises if a transparent relationship -

Chapter 4 the Internationalized Text and Its Localized Variations

Chapter 4 The internationalized text and its localized variations: A parallel analysis of blurbs localized from English into Arabic and French Madiha Kassawat Université Sorbonne Nouvelle (ESIT) In an increasingly globalized world, accessibility to digital content has become in- dispensable for people around the world. This accessibility would not be possible without translation which plays an important role in linguistic and cultural media- tion, as well as in marketing. As the majority of products is promoted for and sold on the internet, their web pages are often localized based on the market, including the language and the culture. The required speed in this type of work, its tools and process play a remarkable role which influences the quality of the localized texts. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze these texts, explore the different interpreta- tions of a text in several languages and cultures, and the adaptation level which should convince the consumer to purchase the product. This pilot study is an at- tempt to compare the product descriptions provided in English and localized into Arabic and several French versions. The results show the relationship between the international text and the localized texts on the linguistic and cultural levels. 1 Introduction We are living in a globalized world where translation is a daily-lived practice (Ladmiral 2014). The majority of translated texts nowadays are not literary but utilitarian (Le Disez 2004). At the same time, the digital environment is consid- ered a decisive channel of marketing. It absorbs increasingly between 20 to 30 Madiha Kassawat. 2021. The internationalized text and its localized variations: A parallel anal- ysis of blurbs localized from English into Arabic and French.