'Family' in BBC Pre-School Television Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PSB Report Definitions

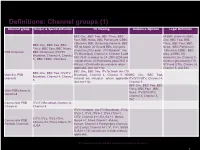

Definitions: Channel groups (1) Channel group Output & Spend definition TV Viewing Audience Opinion Legal Definition BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC All BBC channels (BBC Four, BBC News, BBC Parliament, CBBC, One, BBC Two, BBC CBeebies, BBC streaming channels, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC BBC One, BBC Two, BBC HD (to March 2013) and BBC Olympics News , BBC Parliament Three, BBC Four, BBC News, channels (2012 only). ITV Network* (inc ,CBeebies, CBBC, BBC PSB Channels BBC Parliament, ITV/ITV ITV Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5 and Alba, all BBC HD Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel S4C (S4C is added to C4 2008-2009 and channels), the Channel 3 5,, BBC CBBC, CBeebies excluded from 2010 onwards post-DSO in services (provided by ITV, Wales). HD variants are included where STV and UTV), Channel 4, applicable (but not +1s). Channel 5, and S4C. BBC One, BBC Two, ITV Network (inc ITV BBC One, BBC Two, ITV/ITV Main five PSB Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5. HD BBC One, BBC Two, Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel channels variants are included where applicable ITV/STV/UTV, Channel 4, 5 (but not +1s). Channel 5 BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four , BBC Main PSB channels News, ITV/STV/UTV, combined Channel 4, Channel 5, S4C Commercial PSB ITV/ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channels Channel 5 ITV+1 Network (inc ITV Breakfast) , ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV3+1, ITV4, ITV4+1, CITV, Channel 4+1, E4, E4 +1, More4, CITV, ITV2, ITV3, ITV4, Commercial PSB More4 +1, Film4, Film4+1, 4Music, 4Seven, E4, Film4, More4, 5*, Portfolio Channels 4seven, Channel 4 Paralympics channels 5USA (2012 only), Channel 5+1, 5*, 5*+1, 5USA, 5USA+1. -

Workshop Briefing

King’s Research Portal Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Steemers, J. H., Sakr, N., & Singer, C. (2018). Facilitating Arab-European Dialogue: Consolidated Report on an AHRC Project for Impact and Engagement: Children's Screen Content in an Era of Forced Migration - 8 October 2017 to 3 November 2018. King's College London. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS with SUNRISE TV TV Channel List for Printing

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS WITH SUNRISE TV TV channel list for printing Need assistance? Hotline Mon.- Fri., 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. Sat. - Sun. 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. 0800 707 707 Hotline from abroad (free with Sunrise Mobile) +41 58 777 01 01 Sunrise Shops Sunrise Shops Sunrise Communications AG Thurgauerstrasse 101B / PO box 8050 Zürich 03 | 2021 Last updated English Welcome to Sunrise TV This overview will help you find your favourite channels quickly and easily. The table of contents on page 4 of this PDF document shows you which pages of the document are relevant to you – depending on which of the Sunrise TV packages (TV start, TV comfort, and TV neo) and which additional premium packages you have subscribed to. You can click in the table of contents to go to the pages with the desired station lists – sorted by station name or alphabetically – or you can print off the pages that are relevant to you. 2 How to print off these instructions Key If you have opened this PDF document with Adobe Acrobat: Comeback TV lets you watch TV shows up to seven days after they were broadcast (30 hours with TV start). ComeBack TV also enables Go to Acrobat Reader’s symbol list and click on the menu you to restart, pause, fast forward, and rewind programmes. commands “File > Print”. If you have opened the PDF document through your HD is short for High Definition and denotes high-resolution TV and Internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari...): video. Go to the symbol list or to the top of the window (varies by browser) and click on the print icon or the menu commands Get the new Sunrise TV app and have Sunrise TV by your side at all “File > Print” respectively. -

The Future of The

The Future of Public Service Broadcasting Some thoughts Stephen Fry Before I can even think to presume to dare to begin to expatiate on what sort of an organism I think the British Broadcasting Corporation should be, where I think the BBC should be going, how I think it and other British networks should be funded, what sort of programmes it should make, develop and screen and what range of pastries should be made available in its cafés and how much to the last penny it should pay its talent, before any of that, I ought I think in justice to run around the games field a couple of times puffing out a kind of “The BBC and Me” mini‐biography, for like many of my age, weight and shoe size, the BBC is deeply stitched into my being and it is important for me as well as for you, to understand just how much. Only then can we judge the sense, value or otherwise of my thoughts. It all began with sitting under my mother’s chair aged two as she (teaching history at the time) marked essays. It was then that the Archers theme tune first penetrated my brain, never to leave. The voices of Franklin Engelman going Down Your Way, the women of the Petticoat Line, the panellists of Twenty Questions, Many A Slip, My Word and My Music, all these solid middle class Radio 4 (or rather Home Service at first) personalities populated my world. As I visited other people’s houses and, aged seven by now, took my own solid state transistor radio off to boarding school with me, I was made aware of The Light Programme, now Radio 2, and Sparky’s Magic Piano, Puff the Magic Dragon and Nelly the Elephant, I also began a lifelong devotion to radio comedy as Round The Horne, The Clitheroe Kid, I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again, Just A Minute, The Men from The Ministry and Week Ending all made themselves known to me. -

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

Save Kids’ TV Campaign British children’s television - on the BBC, Channel 4, ITV and Five - has been widely acknowledged as amongst the most creative and innovative in the world. But changes in children’s viewing patterns, and the ban on certain types of advertising to children, are putting huge strains on commercial broadcasters. Channel 4 no longer makes children’s programmes and ITV (until recently the UK’s second largest kids’ TV commissioner) has ceased all new children’s production. They are deserting the children’s audience because it doesn’t provide enough revenue. Channel FIVE have cut back their children’s programming too. The international channels - Disney, Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network - produce some programming here, but not enough to fill the gap, and much of that has to be international in its focus so that it can be used on their channels in other territories. The recent Ofcom report on the health of children’s broadcasting in the UK has revealed that despite the appearance of enormous choice in children’s viewing, the many channels available offer only a tiny number of programmes produced in the UK with British kids’ interests at their core. The figures are shocking – only 1% of what’s available to our kids is new programming made in the UK. To help us save the variety and quality of children’s television in the UK sign the e-petition on the 10 Downing Street website or on http://www.SaveKidsTV.org.uk ends Save Kids' TV - Name These Characters and Personalities 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Help save the quality in UK children's television Go to www.savekidstv.org.uk Save Kids TV - Answers 1 Parsley The Lion The Herbs/The Adventures of Parsley 2 Custard Roobarb and Custard 3 Timothy Claypole Rentaghost 4 Chorlton Chorlton and the Wheelies 5 Aunt Sally Worzel Gummidge 6 Errol The Hamster Roland's Rat Race, Roland Rat on TV-AM etc 7 Roland Browning Grange Hill 8 Floella Benjamin TV Presenter 9 Wizbit Wizbit 10 Zelda Terrahawks 11 Johnny Ball Presenter 12 Nobby The Sheep Ghost Train, It's Wicked, Gimme 5 etc. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Why Can't the Daily Mail Eat Humble Pie Over MMR?

reBOOKS • CD ROMSviews • ART • WEBSITES • MEDIA • PERSONAL VIEWS • SOUNDINGS ful role of the media in the course of the of guilt over having had their children MMR controversy. immunised. It is true that the MMR-autism scare did Phillips is one of many journalists (by not start in the press. Both a reputable Lon- no means confined to the tabloids) who don teaching hospital and a prestigious have endorsed the anti-MMR campaign. medical journal allowed the scare to start. They have provided a voice for middle class Yet, once Wakefield decided to go public anxieties about environmental threats and Why can’t the Daily with his anti-MMR campaign, the media for the distrust of established sources of played a major part in promoting the scare. authority in science, medicine, and politics Mail eat humble pie Phillips’s response to the Cochrane study that have led some parents to reject MMR. follows the familiar themes of numerous Some journalists, writing as celebrity par- over MMR? anti-MMR articles over the years, including ents, have followed the principles of the several by Phillips herself. “journalism of attachment” popularised in recent military conflicts. This requires a he recent publication of a Cochrane Phillips’s article is scientifically flawed. high level of emotional engagement but no systematic review concluding that She seems to misunderstand the nature of a specialist knowledge of the subject (special- there is “no credible evidence” of a systematic review and to misinterpret any T criticism of studies of MMR safety, or any ist medical and scientific correspondents link between the measles, mumps, and have generally rejected the MMR-autism rubella (MMR) vaccine and either inflamma- expression of uncertainty about their link). -

Official Report

Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee Thursday 29 October 2020 Session 5 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.parliament.scot or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000 Thursday 29 October 2020 CONTENTS Col. DECISION ON TAKING BUSINESS IN PRIVATE ....................................................................................................... 1 SUBORDINATE LEGISLATION............................................................................................................................... 2 Census (Scotland) Amendment Order 2020 [Draft] ..................................................................................... 2 BBC ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS ........................................................................................................... 11 CULTURE, TOURISM, EUROPE AND EXTERNAL AFFAIRS COMMITTEE 25th Meeting 2020, Session 5 CONVENER *Joan McAlpine (South Scotland) (SNP) DEPUTY CONVENER *Claire Baker (Mid Scotland and Fife) (Lab) COMMITTEE MEMBERS *Annabelle Ewing (Cowdenbeath) (SNP) *Kenneth Gibson (Cunninghame North) (SNP) *Ross Greer (West Scotland) (Green) Dean Lockhart (Mid Scotland and Fife) (Con) *Oliver Mundell (Dumfriesshire) (Con) *Stewart Stevenson (Banffshire and Buchan Coast) (SNP) *Beatrice Wishart (Shetland Islands) (LD) *attended THE FOLLOWING ALSO PARTICIPATED: Steve Carson (BBC Scotland) Fiona Hyslop (Cabinet Secretary for Economy, Fair Work -

Download the Art of Smallfilms: the Work of Oliver Postgate & Peter

THE ART OF SMALLFILMS: THE WORK OF OLIVER POSTGATE & PETER FIRMIN DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Oliver Postgate, Peter Firmin, Stewart Lee, Jonny Trunk, Richard Embray | 320 pages | 24 Feb 2015 | FOUR CORNERS BOOKS | 9781909829022 | English | London, United Kingdom RIP Oliver Postgate 1925-2008 Retrieved 23 September Surprisingly for the Guardian, they are recommending a man who hates the Top Gear presenters and co wrote a hit show that offended Christians. Amazon Business Service for business customers. Or push it down hill. I could just close my eyes, but fantasizing about punching Stewart Lee is still more fun than sitting in complete, stony silence. No The Art of Smallfilms: The Work of Oliver Postgate & Peter Firmin, if we don't laugh at your material then it's just not good enough. Arnold Schwarzenegger. A fabulous big book for all oliver postgate and peter firmin fans. More Details To gain experience, he accepted a contract as a television director in the BBC Children's Department inon a show entitled Little Lauraanother animated series made on film, written and drawn by V. Gianmarco Milesi. Categories : Television production companies of the United Kingdom British animation studios Mass media companies established in British companies established in Ivor the engine, bagpuss, clangers, pogles, noggin, tottie and pinny are all included. Bruce Lee. He addressed an insular cadre of socially challenged, prematurely middle-aged, pseudo-intellectual men, I thought. Add to Wish List. In short, if you're a bigoted, socialist worker, civil servant, teacher, social worker or NHS employee then Stuart Lee is the comedian for you. -

Known Nursery Rhymes Residencies Fruit Eaten Remembered World

13 Nov. 1995 – Leah Betts in coma after taking ecstasy 26 Sep. 2007 – Myanmar government, using extreme force, cracks down on protests Blockbusters Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1982 Pratchett, T. – Soul Music Celery Hilden, Linda The Tortoise and the Eagle Beverly Hills Cop Goodfellas Speed Peanut Brittle Dial M for Murder Russ Abbott Arena Coast To Coast Gary Numan Live Rammstein Vast Ready to Rumble (Dreamcast) Known Nursery Rhymes 22 Nov. 1995 – Rosemary West sentenced to life imprisonment 06 Oct. 2007 – Musharraf breezes to easy re-election in Pakistan Buckaroo Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1984 Pratchett, T. - Sorcery Chard Hill, Debbie The Jackdaw and the Fox Beverly Hills Cop 2 The Goonies Speed 2 Pear Drops Dinnerladies The Ruth Rendell Mysteries Aretha Franklin Cochine Gene McDaniels The Living End Ramones Vegastones Resident Evil (Various) All Around the Mulberry Bush 14 Dec. 1995 – Bosnia peace accord 05 Nov. 2007 – Thousands of lawyers take to the streets to protest the state of emergency rule in Pakistan. Chess Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1985 Pratchett, T. – The Streets of Ankh-Morpork Chickpea Hiscock, Anna-Marie The Boy and the Wolf Bicentennial Man The Good, The Bad and the Ugly Spider Man Picnic Doctor Who The Saint Armand Van Helden Cockney Rebel Gene Pitney Lizzy Mercier Descloux Randy Crawford The Velvet Underground Robocop (Commodore 64) As I Was Going to St. Ives 02 Jan. 1996 – US Peacekeepers enter Bosnia 09 Nov. 2007 – Police barricade the city of Rawalpindi where opposition leader Benazir Bhutto plans a protest Chinese Checkers Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1988 Pratchett, T. -

UK@Kidscreen Delegation Organised By: Contents

© Bear Hunt Films Ltd 2016 © 2016 Brown Bag Films and Technicolor Entertainment Services France SAS Horrible Science Shane the Chef © Hoho Entertainment Limited. All Rights Reserved. ©Illuminated Films 2017 © Plug-in Media Group Ltd. UK@Kidscreen delegation organised by: Contents Forewords 3-5 KidsCave Entertainment Productions 29 David Prodger 3 Kidzilla Media 30 Greg Childs and Sarah Baynes 4-5 Kindle Entertainment 31 Larkshead Media 32 UK Delegate Companies 6-53 Lupus Films 33 Accorder Music 6 MCC Media 34 Adorable Media 7 Mezzo Kids 35 Animation Associates 8 Myro, On A Mission! 36 Blink Industries 9 Blue-Zoo Productions 10 Ollie’s Edible Adventures/MRM Inc 37 Cloth Cat Animation 11 Plug-in Media 38 DM Consulting 12 Raydar Media 39 Enabling Genius 13 Reality Studios 40 Eye Present 14 Serious Lunch 41 Factory 15 Sixth Sense Media 42 Film London 16 Spider Eye 43 Fourth Wall Creative 17 Studio aka 44 Fudge Animation Studios 18 Studio Liddell 45 Fun Crew 19 The Brothers McLeod 46 Grass Roots Media 20 The Children’s Media Conference 47 History Bombs Ltd 21 The Creative Garden 48 HoHo Rights 22 Three Arrows Media 49 Hopster 23 Thud Media 50 Ideas at Work 24 Tiger Aspect Productions 51 Illuminated Productions 25 Tom Angell Ltd 52 ITV PLC 26 Visionality 53 Jellyfish Pictures 27 Jetpack Distribution 28 Contacts 54 UK@Kidscreen 2017 3 Foreword By David Prodger, Consul General, Miami, Foreign and Commonwealth Office I am delighted to welcome such an impressive UK delegation to Kidscreen which is taking place in Miami for the third time.