Film Review First Reformed (Paul Schrader, US 2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

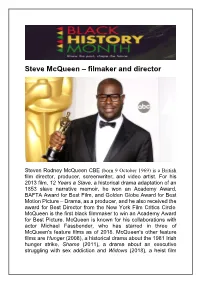

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

El Último Cine

Cartel alemán de Estambul 65 (Antonio Isasi Isasmendi, 1965). Bilbao (Bigas Luna, 1978) SuscripciónSuscripción a la a alertala alerta del del programa programa mensual mensual del del cine cine Doré Doré en: en: http://www.mcu.es/suscripciones/loadAlertForm.do?cache=init&layout=alertasFilmo&area=FILMO http://www.mcu.es/suscripciones/loadAlertForm.do?cache=init&layout=alertasFilmo&area=FILMO Ciclos en preparación: Marzo: William Wellman (y II) CiclosAño enDual preparación: España-Japón 3XDOC Febrero:Ellas crean: Nueve cineastas argentinas Muestra de cine filipino (y II) MuestraRecuerdo de cinede: Jesúsbúlgaro Franco, Alfredo Landa, Lolita Sevilla … CasaCentenario Asia presenta: de Rafael ‘El últimoGil (y II) cine iraní’ RecuerdoJirí Menzel de Maureen O´Hara Mikhail Romm Jirí Menzel Brian de Palma Alberto Lattuada Alberto Lattuada Luc Moullet GOBIERNO MINISTERIO DE ESPAÑA DE EDUCACIÓN, CULTURA Y DEPORTE ENERO 2016 Centenario de Harold Lloyd Robert Bresson Recuerdo de Vicente Aranda Costa-Gavras Muestra de cine filipino Muestra de cine palestino (y II) Muestra de cine rumano (y II) Costa-Gavras Mike de Leon rodando Itim (1976) Agradecimientos enero 2016: A Contracorriente Films, Barcelona; Antonio Isasi Jr., Barcelona; Cinemateca Portuguesa, Lisboa; Film Development Council of the Philippines (Briccio Santos, presidente, y Teodoro Granados, director ejecutivo), Makati; Flat Cinema, Madrid; Gaumont, Harold Lloyd Entertainment, Inc. (Sara Juárez), Los Ángeles; Instituto Cultural Rumano de Madrid (Ioana Anghel, Ovidiu Miron); Lola Films, Madrid; Multivideo S.L, Madrid; Oesterreichisches Filmmuseum (Regina Schlagnitweit ), Viena; Plataforma de Divulgación UCM (Ricardo Jimeno y José Antonio Jiménez de las Heras), Madrid; Tamasa Distribu- tion, París; Universal Pictures; Video Mercury, Madrid; Warner Bros. Pictures int. -

Directing the Narrative Shot Design

DIRECTING THE NARRATIVE and SHOT DESIGN The Art and Craft of Directing by Lubomir Kocka Series in Cinema and Culture © Lubomir Kocka 2018. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Cinema and Culture Library of Congress Control Number: 2018933406 ISBN: 978-1-62273-288-3 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. CONTENTS PREFACE v PART I: DIRECTORIAL CONCEPTS 1 CHAPTER 1: DIRECTOR 1 CHAPTER 2: VISUAL CONCEPT 9 CHAPTER 3: CONCEPT OF VISUAL UNITS 23 CHAPTER 4: MANIPULATING FILM TIME 37 CHAPTER 5: CONTROLLING SPACE 43 CHAPTER 6: BLOCKING STRATEGIES 59 CHAPTER 7: MULTIPLE-CHARACTER SCENE 79 CHAPTER 8: DEMYSTIFYING THE 180-DEGREE RULE – CROSSING THE LINE 91 CHAPTER 9: CONCEPT OF CHARACTER PERSPECTIVE 119 CHAPTER 10: CONCEPT OF STORYTELLER’S PERSPECTIVE 187 CHAPTER 11: EMOTIONAL MANIPULATION/ EMOTIONAL DESIGN 193 CHAPTER 12: PSYCHO-PHYSIOLOGICAL REGULARITIES IN LEFT-RIGHT/RIGHT-LEFT ORIENTATION 199 CHAPTER 13: DIRECTORIAL-DRAMATURGICAL ANALYSIS 229 CHAPTER 14: DIRECTOR’S BOOK 237 CHAPTER 15: PREVISUALIZATION 249 PART II: STUDIOS – DIRECTING EXERCISES 253 CHAPTER 16: I. -

Pdf-Collections-.Pdf

1 Directors p.3 Thematic Collections p.21 Charles Chaplin • Abbas Kiarostami p.4/5 Highlights from Lobster Films p.22 François Truffaut • David Lynch p.6/7 The RKO Collection p.23 Robert Bresson • Krzysztof Kieslowski p.8/9 The Kennedy Films of Robert Drew p.24 D.W. Griffith • Sergei Eisenstein p.10/11 Yiddish Collection p.25 Olivier Assayas • Alain Resnais p.12/13 Themes p.26 Jia Zhangke • Gus Van Sant p.14/15 — Michael Haneke • Xavier Dolan p.16/17 Buster Keaton • Claude Chabrol p.18/19 Actors p.31 Directors CHARLES CHAPLIN THE COMPLETE COLLECTION AVAILABLE IN 2K “A sort of Adam, from whom we are all descended...there were two aspects of — his personality: the vagabond, but also the solitary aristocrat, the prophet, the The Kid • Modern Times • A King in New York • City Lights • The Circus priest and the poet” The Gold Rush • Monsieur Verdoux • The Great Dictator • Limelight FEDERICO FELLINI A Woman of Paris • The Chaplin Revue — Also available: short films from the First National and Keystone collections (in 2k and HD respectively) • Documentaries Charles Chaplin: the Legend of a Century (90’ & 2 x 45’) • Chaplin Today series (10 x 26’) • Charlie Chaplin’s ABC (34’) 4 ABBas KIAROSTAMI NEWLY RESTORED In 2K OR 4K “Kiarostami represents the highest level of artistry in the cinema” — MARTIN SCORSESE Like Someone in Love (in 2k) • Certified Copy (in 2k) • Taste of Cherry (soon in 4k) Shirin (in 2k) • The Wind Will Carry Us (soon in 4k) • Through the Olive Trees (soon in 4k) Ten & 10 on Ten (soon in 4k) • Five (soon in 2k) • ABC Africa (soon -

This Is a Title

http://dx.doi.org/10.14236/ewic/RESOUND19.6 The Primacy of Sound in Robert Bresson’s Films Amresh Sinha School of Visual Arts 209 E 23rd St, New York, NY 10010 [email protected] Sound and Image, in ideal terms, should have equal position in the film. But somehow, sound always plays the subservient role to the image. In fact, the introduction of sound in the cinema for the purists was the end of movies and the beginning of the talkies. The purists thought that sound would be the ‘deathblow’ to the art of movies. No less revolutionary a director than Eisenstein himself viewed synchronous sound with suspicion and advocated a non-synchronous contrapuntal sound. But despite opposition, the sound pictures became the norm in 1927, after the tremendous success of The Jazz Singer. In this paper, I will discuss the work of French director Robert Bresson, whose films privilege the mode of sound over the image. Bresson’s films challenge the traditional hierarchical relationship of sight and sound, where the former’s superiority is considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to lend a new dimension to the cinematographic art. The liberation of sound is the liberation of cinema from its bondage to sight. Bresson, Sound, Image, Music, Voiceover, Inner Monologue, Diegetic, Non-Diegetic. 1. INTRODUCTION considered indispensable. The prominence of sound is the principle strategy of subverting the Films are essentially made of two major imperial domain of sight, the visual, but the aural ingredients—image and sound—both independent implications also provide Bresson the opportunity to of each other. -

PAJ77/No.03 Chin-C

AIN’T NO SUNSHINE The Cinema in 2003 Larry Qualls and Daryl Chin s 2003 came to a close, the usual plethora of critics’ awards found themselves usurped by the decision of the Motion Picture Producers Association of A America to disallow the distribution of screeners to its members, and to any organization which adheres to MPAA guidelines (which includes the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences). This became the rallying cry of the Independent Feature Project, as those producers who had created some of the most notable “independent” films of the year tried to find a way to guarantee visibility during award season. This issue soon swamped all discussions of year-end appraisals, as everyone, from critics to filmmakers to studio executives, seemed to weigh in with an opinion on the matter of screeners. Yet, despite this media tempest, the actual situation of film continues to be precarious. As an example, in the summer of 2003 the distribution of films proved even more restrictive, as theatres throughout the United States were block-booked with the endless cycle of sequels that came from the studios (Legally Blonde 2, Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle, Terminator 3, The Matrix Revolutions, X-2: X-Men United, etc.). A number of smaller films, such as the nature documentary Winged Migration and the New Zealand coming-of-age saga Whale Rider, managed to infiltrate the summer doldrums, but the continued conglomeration of distribution and exhibition has brought the motion picture industry to a stultifying crisis. And the issue of the screeners was the rallying cry for those working on the fringes of the industry, the “independent” producers and directors and small distributors. -

Film, Philosophy Andreligion

FILM, PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION Edited by William H. U. Anderson Concordia University of Edmonton Alberta, Canada Series in Philosophy of Religion Copyright © 2022 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy of Religion Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942573 ISBN: 978-1-64889-292-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: "Rendered cinema fimstrip", iStock.com/gl0ck To all the students who have educated me throughout the years and are a constant source of inspiration. It’s like a splinter in your mind. ~ The Matrix Table of contents List of Contributors xi Acknowledgements xv Introduction xvii William H. -

The Actor’S Craft Pp.7-18

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Howe, William (2015) A Cinema of Happenings: Exploring Improvisation as Process in Filmmaking. Master of Philosophy (MPhil) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/62458/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html A CINEMA OF HAPPENINGS Exploring Improvisation as Process in Filmmaking Will Howe Submission for MPhil in Drama: Practice as Research ABSTRACT This thesis supports a practice-based-research project that examines differing methodologies of improvisation across the production of four film exercises: Fallen Angels (2005), Blood Offering (2005), Birdman (2009) and The Graduate -

Christianity and the Climate Crisis in Auteur Cinema

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 3-10-2021 "Will God Forgive Us?": Christianity and the Climate Crisis in Auteur Cinema Margaret Alice Parson Louisiana State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Parson, Margaret Alice, ""Will God Forgive Us?": Christianity and the Climate Crisis in Auteur Cinema" (2021). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5477. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5477 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “WILL GOD FORGIVE US?”: CHRISTIANITY AND THE CLIMATE CRISIS IN AUTEUR CINEMA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Margaret Alice Parson B.A., Otterbein University, 2015 M.A., Ball State University, 2017 May 2021 For Tegan ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation, as with all dissertations, is a communal act. Without the massive support of my community, it never would have come into being. Most significantly, Dr. Bryan McCann. This project was completed because of your empathy and guidance. I can never thank you enough. The other members of my committee, Drs. Mack, Saas, and Shaffer have all offered their expertise and kindness in this project’s growth, and I of course am indebted to them for their comments and encouragement.