The Spiritual and Film: Two Test Cases from 1947

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fables and Distances Where God Put the West Spring

SPRING |SUMMER 6 20 2013 14 36 42+ MOVING PICTURES The Films of Farona Konopak FABLES AND DISTANCES DRESSING THE WEST Filmmaking with costume designer with DOTTIE DIAMANT in the Southwest CATHY SMITH jou rns jou Technicolor ROCKS A starring Sedona’s own WHERE GOD PUT o JOHN MURRAY THE WEST JOE O’NEILL Production a documentary 28 S ( Moab’s Movie featuring JUST LIKE IN Museum BETTE STANTON THE MOVIES by SAM WAINER as recorded by script by CINDY HARDGRAVE RENNARD STRICKLAND meep meep! and that’s all, folks! John A. MurrAy am sitting on a rock overlooking Monument Valley. It is the hour before sunrise. The sky to the west, over Oljeto Mesa, is still sprinkled with a few stars. The sky to the east, over the distant Chuska Mountains, is as pink as the palm of my hand. Even as I watch, a lens of red light is forming on the horizon. Before me are three great buttes—Left Mitten, Merrick, and Right Mitten. The names Imay not be familiar, but almost everyone has seen the formations, for they have been fables AND featured in dozens of films. For vast distances the landscape is perfectly flat, and then suddenly there are these three heavy solid rocks, each rising to the height of a one- hundred-story building. As the light comes up on the earth, the country begins to reveal distances its secrets. It is a desert land, spare and disciplined, and there is no fat on it. The colors are dry and sun-washed, like the colors of Anasazi pottery sherds. -

La Mémoire De La Seconde Guerre Mondiale Au Cinéma - 1946 : La Bataille Du Rail, René Clément : Hommage Aux Cheminots Résistants

La mémoire de la Seconde Guerre mondiale au cinéma - 1946 : La Bataille du Rail, René Clément : hommage aux cheminots résistants. Grand prix du Jury au festival de Cannes. - 1946 : Le Père tranquille, René Clément : un retraité qui cultive des orchidées et semble lâche est en fait le chef de la Résistance de la région. - 1949 : Le Silence de la mer, Jean-Pierre Melville : un officier allemand loge chez un grand-père et sa petite fille qui refusent de lui parler. Premier livre édité par les Editions de Minuit, maison d’édition de la Résistance, pendant la guerre. L’auteur est Vercors. - 1956 : Nuit et Brouillard, Alain Resnais. - 1959 : La Vache et le Prisonnier, Henri Verneuil, un prisonnier de guerre français tente de s’évader avec une vache. Enorme succès, un des films les plus diffusés à la télévision. - 1962 : Le Jour le plus long, Andrew Marton, Bernhard Wicki et Ken Annakin : le débarquement en Normandie. - 1963 : La Grande Evasion, John Sturges, l’évasion collective de prisonniers de guerre. - 1966 : Paris brûle-t-il ? René Clément. Récit de la libération de Paris. De Gaulle au pouvoir, mais si les communistes sont mécontents, électriciens et machinistes refuseront de travailler. Film hollywoodien (Kirk Douglas, Alain Delon, Jean Paul Belmondo, Orson Welles…). Les communistes (le mot n’est quasiment pas prononcé, il s’agit de Rol-Tanguy et des rolistes) apparaissent comme des agités, général Chaban représente le bon sens et la modération. Bidault (ex président du CNR mais mal vu en 1966) n’est pas représenté dans le film. Enorme couverture médiatique pour la sortie du film. -

Wagon Master Caravana De Paz 1950, USA

Wagon Master Caravana de paz 1950, USA Prólogo: Una familia de bandoleros, los Cleggs, atraca un banco asesinando D: John Ford; G: Frank S. Nugent, a sangre fría a uno de sus empleados. Patrick Ford, John Ford; Pr: Lowell J. Farrell, Argosy Pictures; F: Bert Títulos de crédito: imágenes de una caravana de carretas atravesando un Glennon; M: Richard Hageman; río, rodando a través de (como dice la canción que las acompaña) “ríos y lla- Mn: Jack Murray, Barbara Ford; nuras, arenas y lluvia”. A: Ben Johnson, Joanne Dru, Harry Carey Jr., Ward Bond, 1849. A la pequeña población de Cristal City llegan dos tratantes de caballos, Charles Kemper, Alan Mowbray, Travis (Ben Johnson) y Sandy (Harry Carey Jr.) con la finalidad de vender sus Jane Darwell, Ruth Clifford, Russell recuas. Son abordados por un grupo de mormones que desean comprarles los Simpson, Kathleen O’Malley, caballos y contratarles como guías para que conduzcan a su gente hasta el río James Arness, Francis Ford; San Juan, más allá del territorio navajo, hasta “el valle que el señor nos tiene B/N, 86 min. DCP, VOSE reservado, que ha reservado a su pueblo para que lo sembremos y lo cultive- mos y lo hagamos fructífero a sus ojos”. Los jóvenes aceptan la primera oferta pero rechazan la segunda. A la mañana siguiente la caravana mormona se pone en camino, vigilada muy de cerca por las intolerantes gentes del pueblo. Travis y Sandy observan la partida sentados en una cerca. De repente, en apenas dos versos de la can- ción que entona Sandy, el destino da un vuelco y los jóvenes deciden incorpo- rarse al viaje hacia el oeste: “Nos vemos en el río. -

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

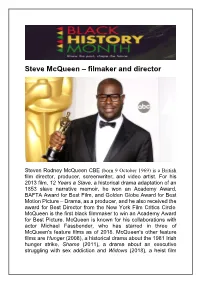

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The Holy Fool in Late Tarkovsky

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha Journal of Religion & Film Volume 18 | Issue 1 Article 45 3-31-2014 The olH y Fool in Late Tarkovsky Robert O. Efird Virginia Tech, [email protected] Recommended Citation Efird, Robert O. (2014) "The oH ly Fool in Late Tarkovsky," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 18 : Iss. 1 , Article 45. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol18/iss1/45 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The olH y Fool in Late Tarkovsky Abstract This article analyzes the Russian cultural and religious phenomenon of holy foolishness (iurodstvo) in director Andrei Tarkovsky’s last two films, Nostalghia and Sacrifice. While traits of the holy fool appear in various characters throughout the director’s oeuvre, a marked change occurs in the films made outside the Soviet Union. Coincident with the films’ increasing disregard for spatiotemporal consistency and sharper eschatological focus, the character of the fool now appears to veer off into genuine insanity, albeit with a seemingly greater sensitivity to a visionary or virtual world of the spirit and explicit messianic task. Keywords Andrei Tarkovsky, Sacrifice, Nostalghia, Holy Foolishness Author Notes Robert Efird is Assistant Professor of Russian at Virginia Tech. He holds a PhD in Slavic from the University of Virginia and is the author of a number of articles dealing with Russian and Soviet cinema. -

A.U.I. Trustee Scholarships Are Established

VOLUME 18, NUMBER 13 Published by the BNL Personnel Office JANUARY 20, 1965 BERA FILM SERIES PURPLE NOON A.U.I. TRUSTEE SCHOLARSHIPS ARE ESTABLISHED A scholarship program for the children of regular employees of Brookhaven National Laboratory and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory has been established by the Board of Trustees of Associated Universities, Inc. Dr. Maurice Goldhaber, Director, announced the creation of the A.U.I. Trustee Scholarships to all Brookhaven employees on January 18. Under the new program, up to ten scholarships each year will be made avail- able to the children of regular BNL employees. They will carry a stipend of up to $900 per year. For those who maintoin satisfactory progress in school, the scholor- ships will be renewoble for up to three additional years. Winners of the awards may attend any accredited college or university in the United States and may select any course of study leading to a bachelor’s degree. Thurs., Jan. 21 - lecture Hall - 8:30 p.m. The scholarships will be granted on o strictly competitive basis, independent Rene Clement (“Forbidden Games,” of financial need and the existence of other forms of aid to the student. Winners “Gervaise”) has here fashioned a highly will be selected on the basis of their secondary school academic records and gen- entertaining murder thriller, beautifully eral aptitude for college work as indicated by achievement and aptitude tests. photographed in color by Henri Decae The Laboratory will not be involved in the processing of applications or the (“400 Blows, ” “The Cousins,” “Sundays determination of scholarship winners. -

CFP Refocus: the Films of Andrei Tarkovsky

H-Announce CFP ReFocus: The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky Announcement published by Sergei Toymentsev on Wednesday, August 3, 2016 Type: Call for Publications Date: November 30, 2016 Location: United States Subject Fields: Art, Art History & Visual Studies, Cultural History / Studies, Film and Film History, Humanities, Russian or Soviet History / Studies ReFocus: The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky Andrei Tarkovsky (1932 -1986) is a renowned Russian filmmaker whose work, despite an output of only seven feature films in twenty years, has had a profound influence on international cinema. Famous for languid pacing, long takes, dreamlike imagery, spiritual depth and philosophical allegories, most of his films have gained cult status among cineastes and are often included in various kinds of ranking polls and charts dedicated to the "best movies ever made." Thus, for example, the British Film Institute's "50 Greatest Films of All Time" poll conducted for the film magazine Sight & Sound in 2012 honors three of Tarkovsky's films: Andrei Rublev (1966) is ranked at No. 26, Mirror (1974) at No. 19, and Stalker (1979) at No. 29. Beginning with the late 1980, Tarkovsky's highly complex cinema has continuously attracted scholarly and critical attention in film studies by generating countless hermeneutic challenges and possibilities for film scholars. Almost all intellectual vogues and methodologies in humanities, whether it's feminism, psychoanalysis, poststructuralism, diaspora studies or film-philosophy, have left their interpretative trace on the reception of his work. This ReFocus anthology on Andrei Tarkovsky invites chapter proposals of 200-400 words that would take yet another look at the director's legacy from interdisciplinary perspectives. -

I Think You'll Like It: an Experimental Film

I Think You’ll Like It: An experimental film Self-Determined Major Final Project Proposal Major: Film Readers: Adam Tinkle, Rik Scarce 1 Intro/ Background Through my study of film-making, I have developed a personal affinity for abstract films and nontraditional uses of video as an artistic and abstract medium. Video is often seen as a way to portray an event in the most literal and ‘true-to-life’ way. In studying film studies and production though, I have learned first-hand that no video can be truly objective. Just as any medium is informed by the creator’s point of view and the story they wish to tell, all of the creative tools that a filmmaker can use to make a piece also impact the meaning based on their individual perspective and the influence of their ‘eye’ on the final product. In the abstract works that I have studied, this -wide fascination with telling truth is focused more on deeper and less traditionally observable truths. Films like Hiroshima, Mon Amour, At Land, and Fuses use video to tell truths of the mind, heart, and soul that might otherwise be inexpressible. The layered use of visual elements like color, texture, and imagery, combined with audio layering act as tools to express these truths artistically. The self expression and portrayal of different parts of human experience are immersive and beautiful because of their nontraditional nature in these experimental films. For my final project, I propose creating an experimental 10 minute short film: I Think You’ll Like It, which explores senses, color, and imagination.