The Allusive Auteur: Wes Anderson and His Influences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hole a Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Going Down the 'Wabbit' Hole A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Barrie, Gregg Award date: 2020 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Gregg Barrie PhD Film Studies Thesis University of Dundee February 2021 Word Count – 99,996 Words 1 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Table of Contents Table of Figures ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Declaration ............................................................................................................................................ -

Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2004 Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Custom Citation King, Homay. "Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes' Opening Night and Faces." Camera Obscura 19, no. 2/56 (2004): 105-139, doi: 10.1215/02705346-19-2_56-105. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/40 For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Homay King, “Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes’ Opening Night and Faces,” Camera Obscura 56, v. 19, n. 2 (Summer 2004): 104-135. Free Indirect Affect in Cassavetes’ Opening Night and Faces Homay King How to make the affect echo? — Roland Barthes, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes1 1. In the Middle of Things: Opening Night John Cassavetes’ Opening Night (1977) begins not with the curtain going up, but backstage. In the first image we see, Myrtle Gordon (Gena Rowlands) has just exited stage left into the wings during a performance of the play The Second Woman. In this play, Myrtle acts the starring role of Virginia, a woman in her early sixties who is trapped in a stagnant second marriage to a photographer. Both Myrtle and Virginia are grappling with age and attempting to come to terms with the choices they have made throughout their lives. -

Greenberg (2011)

Greenberg (2011) “You like me so much more than you think you do.” Major Credits: Director: Noah Baumbach Screenplay: Noah Baumbach, from a story by Baumbach and Jennifer Jason Leigh Cinematography: Harris Savides Music: James Murphy Principal Cast: Ben Stiller (Roger Greenberg), Greta Gerwig (Florence), Rhys Ifans (Ivan), Jennifer Jason Leigh (Beth) Production Background: Baumbach, the son of two prominent New York writers whose divorce he chronicled in his earlier feature The Squid and the Whale (2005), co-wrote the screenplay with his then-wife, Jennifer Jason Leigh, who plays the role of Greenberg’s former girlfriend. His friend and sometime collaborator (they wrote The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou together), Wes Anderson, co-produced Greenberg with Leigh. Most of Baumbach’s films to date deal with characters who are disappointed in their lives, which do not conform to their ideal conceptions of themselves. At whatever age—a father in his 40s, his pretentious teenage son (The Squid and the Whale), a college graduate in her late twenties (Frances Ha, 2012)—they struggle to act like grownups. The casting of Greta Gerwig developed into an enduring romantic and creative partnership: Gerwig co-wrote and starred in his next two films, Frances Ha and Mistress America (2015). You can read about Baumbach and Gerwig in Ian Parker’s fine article published in New Yorker, April 29, 2013. Cinematic Qualities: 1. Screenplay: Like the work of one of his favorite filmmakers, Woody Allen, Baumbach’s dramedy combines literate observation (“All the men dress up as children and the children dress as superheroes”) and bitter commentary (“Life is wasted on… people”) with poignant confession (“It’s huge to finally embrace the life you never planned on”). -

Post-Postmodern Cinema at the Turn of the Millennium: Paul Thomas Anderson’S Magnolia

Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos, vol. 24, 2020. Seville, Spain, ISSN 1133-309-X, pp. 1-21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/REN.2020.i24.01 POST-POSTMODERN CINEMA AT THE TURN OF THE MILLENNIUM: PAUL THOMAS ANDERSON’S MAGNOLIA JESÚS BOLAÑO QUINTERO Universidad de Cádiz [email protected] Received: 20 May 2020 Accepted: 26 July 2020 KEYWORDS Magnolia; Paul Thomas Anderson; post-postmodern cinema; New Sincerity; French New Wave; Jean-Luc Godard; Vivre sa Vie PALABRAS CLAVE Magnolia; Paul Thomas Anderson; cine post-postmoderno; Nueva Sinceridad; Nouvelle Vague; Jean-Luc Godard; Vivir su vida ABSTRACT Starting with an analysis of the significance of the French New Wave for postmodern cinema, this essay sets out to make a study of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia (1999) as the film that marks the beginning of what could be considered a paradigm shift in American cinema at the end of the 20th century. Building from the much- debated passing of postmodernism, this study focuses on several key postmodern aspects that take a different slant in this movie. The film points out the value of aspects that had lost their meaning within the fiction typical of postmodernism—such as the absence of causality; sincere honesty as opposed to destructive irony; or the loss of faith in Lyotardian meta-narratives. We shall look at the nature of the paradigm shift to link it to the desire to overcome postmodern values through a recovery of Romantic ideas. RESUMEN Partiendo de un análisis del significado de la Nouvelle Vague para el cine postmoderno, este trabajo presenta un estudio de Magnolia (1999), de Paul Thomas Anderson, como obra sobre la que pivota lo que se podría tratar como un cambio de paradigma en el cine estadounidense de finales del siglo XX. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

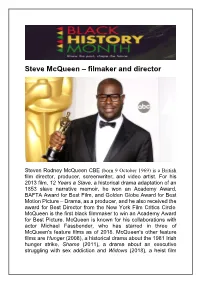

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

The Guardian, April 21, 1969

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 4-21-1969 The Guardian, April 21, 1969 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (1969). The Guardian, April 21, 1969. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WRiGHT STATE -Th e $£***** ) Guardian Volume V April 21, 1969 Freedom Shrine Sanity or lunacy '! rededicated Class hours change On the tenth day of April Announced for Fall nineteen hundred and sixty-nine A major change in the The report indicated that, the Dayton Exchange Club pre- m scheduling of class pi.jods for based on present classroom utili- sented the Rededication of the next Fall was announced at the zation, the projection for next Freedom Shrine to Wright State April 9 meeting of the Academic year indicates a nine room deficit University. The program was con- Council. Classes will be SO min- in the number of classrooms ducted by Robert Whited the utes long on Monday, Wednesday needed a' wak hours. In 1971-72, President of the Exchange Club. and Friday, and 75 minutes long with a .xted en roll men' of Tom Frawley the immediate on Tuesday and Thursday. In a 12,175, ,:ght State would be past president made the introduc- report to the Council of Deans, short 25 classrooms, tion of Clarence J. -

Embargoed Until 12:00PM ET / 9:00AM PT on Tuesday, April 23Rd, 2019

Embargoed Until 12:00PM ET / 9:00AM PT on Tuesday, April 23rd, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 24th ANNUAL NANTUCKET FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES FEATURE FILM LINEUP DANNY BOYLE’S YESTERDAY TO OPEN FESTIVAL ALEX HOLMES’ MAIDEN TO CLOSE FESTIVAL LULU WANG’S THE FAREWELL TO SCREEN AS CENTERPIECE DISNEY•PIXAR’S TOY STORY 4 PRESENTED AS OPENING FAMILY FILM IMAGES AVAILABLE HERE New York, NY (April 23, 2019) – The Nantucket Film Festival (NFF) proudly announced its feature film lineup today. The opening night selection for its 2019 festival is Universal Pictures’ YESTERDAY, a Working Title production written by Oscar nominee Richard Curtis (Four Weddings and a Funeral, Love Actually, and Notting Hill) from a story by Jack Barth and Richard Curtis, and directed by Academy Award® winner Danny Boyle (Slumdog Millionaire, Trainspotting, 28 Days Later). The film tells the story of Jack Malik (Himesh Patel), a struggling singer-songwriter in a tiny English seaside town who wakes up after a freak accident to discover that The Beatles have never existed, and only he remembers their songs. Sony Pictures Classics’ MAIDEN, directed by Alex Holmes, will close the festival. This immersive documentary recounts the thrilling story of Tracy Edwards, a 24-year-old charter boat cook who became the skipper of the first ever all-female crew to enter the Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race. The 24th Nantucket Film Festival runs June 19-24, 2019, and celebrates the art of screenwriting and storytelling in cinema. A24’s THE FAREWELL, written and directed by Lulu Wang, will screen as the festival’s Centerpiece film. -

Moonrise Kingdom"

"Moonrise Kingdom" Screenplay by Wes Anderson and Roman Coppola May 1, 2011 INT. BISHOP’S HOUSE. DAY A landing at the top of a crooked, wooden staircase. There is a threadbare, braided rug on the floor. There is a long, wide corridor decorated with faded paintings of sailboats and battleships. The wallpapers are sun-bleached and peeling at the corners except for a few newly-hung strips which are clean and bright. A small easel sits stored in the corner. Outside, a hard rain falls, drumming the roof and rattling the gutters. A ten-year-old boy in pajamas comes up the steps carefully eating a bowl of cereal as he walks. He is Lionel. Lionel slides open the door to a low cabinet under the window. He takes out a portable record player, puts a disc on the turntable, and sets the needle into the spinning groove. A child’s voice says over the speaker: RECORD PLAYER (V.O.) In order to show you how a big symphony orchestra is put together, Benjamin Britten has written a big piece of music, which is made up of smaller pieces that show you all the separate parts of the orchestra. As Lionel listens, three other children wander out of their bedrooms and down to the landing. The first is an eight-year-old boy in a bathrobe. He is Murray. The second is a nine-year-old boy in white boxer shorts and a white undershirt. He is Rudy. The third is a twelve-year-old girl in a cardigan sweater with knee-high socks and brightly polished, patent-leather shoes. -

Postnormal Imaginings in Wes Anderson's the Darjeeling Limited

Postnormal Imaginings in Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited Perpetuating Orientalist and neocolonial representations, biases, and stereotypes as pretentious comedy is the new creed of the American New Wave Movement JOHN A. SWEENEY THE HISTORY OF THE INDIAN RAILWAY SYSTEM PRESENTS A FABLE SOME 150 YEARS old—one that helped to defne the very topography of the sub-continent and its people. Emphasizing the lasting impact of trains on India, Srinivasan observes, “Railways made India a working and recognizable structure and political and economic entity, at a time when many other forces militated against unity. Through their own internal logic, their transformation of speed and the new dynamic of the economic changes they made possible, the railways defnitively altered the Indian way of life” (Srinivasan, 2006, pxiii). While assisting in the alteration of identities, Indian railways simultaneously united and partitioned the sub-continent on a seemingly unimaginable scale. “If you dug up all the rail track in India and laid it along the equator,” writes Reeves, “you could ride around the world one-and-a- half times.” This enormous enterprise, which occurred when the idea of “India” as an integrated political unit “remained very much an imaginary notion,” originated as the fanciful legacy of British rule, which sought a material means to coalesce its occupation (Reeves, 2006, pxiii). The railway was both the cause and efect of Britain’s colonial sovereignty; the very “idea of establishing and expanding a railway system in India ofered the most vibrant excitement in colonial mind” (Iqbal, 2006, p173). The vast colonial East-West Afairs 75 project was “the work of the capitalist interest in Britain” but it “fourished and expanded frst on ground which was essentially ‘mental’” (Iqbal, 2006, p183). -

Bruce Jackson & Diane Christian Video Introduction to This Week's Film

April 28, 2020 (XL:13) Wes Anderson: ISLE OF DOGS (2018, 101m) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Bruce Jackson & Diane Christian video introduction to this week’s film (with occasional not-very-cooperative participation from their dog, Willow) Click here to find the film online. (UB students received instructions how to view the film through UB’s library services.) Videos: Wes Anderson and Frederick Wiseman in a fascinating Skype conversation about how they do their work (Zipporah Films, 21:18) The film was nominated for Oscars for Best Animated Feature and Best Original Score at the 2019 Academy Isle of Dogs Voice Actors and Characters (8:05) Awards. The making of Isle of Dogs (9:30) CAST Starting with The Royal Tenenbaums in 2001, Wes Isle of Dogs: Discover how the puppets were made Anderson has become a master of directing high- (4:31) profile ensemble casts. Isle of Dogs is no exception. Led by Bryan Cranston (of Breaking Bad fame, as Weather and Elements (3:18) well as Malcolm in the Middle and Seinfeld), voicing Chief, the cast, who have appeared in many Anderson DIRECTOR Wes Anderson films, includes: Oscar nominee Edward Norton WRITING Wes Anderson wrote the screenplay based (Primal Fear, 1996, American History X, 1998, Fight on a story he developed with Roman Coppola, Club, 1999, The Illusionist, 2006, Birdman, 2014); Kunichi Nomura, and Jason Schwartzman. Bob Balaban (Midnight Cowboy, 1969, Close PRODUCERS Wes Anderson, Jeremy Dawson, Encounters