94100-TRIAMS Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scraps of Hope in Banda Aceh

Marjaana Jauhola Marjaana craps of Hope in Banda Aceh examines the rebuilding of the city Marjaana Jauhola of Banda Aceh in Indonesia in the aftermath of the celebrated SHelsinki-based peace mediation process, thirty years of armed conflict, and the tsunami. Offering a critical contribution to the study of post-conflict politics, the book includes 14 documentary videos Scraps of Hope reflecting individuals’ experiences on rebuilding the city and following the everyday lives of people in Banda Aceh. Scraps of Hope in Banda Aceh Banda in Hope of Scraps in Banda Aceh Marjaana Jauhola mirrors the peace-making process from the perspective of the ‘outcast’ and invisible, challenging the selective narrative and ideals of the peace as a success story. Jauhola provides Gendered Urban Politics alternative ways to reflect the peace dialogue using ethnographic and in the Aceh Peace Process film documentarist storytelling. Scraps of Hope in Banda Aceh tells a story of layered exiles and displacement, revealing hidden narratives of violence and grief while exposing struggles over gendered expectations of being good and respectable women and men. It brings to light the multiple ways of arranging lives and forming caring relationships outside the normative notions of nuclear family and home, and offers insights into the relations of power and violence that are embedded in the peace. Marjaana Jauhola is senior lecturer and head of discipline of Global Development Studies at the University of Helsinki. Her research focuses on co-creative research methodologies, urban and visual ethnography with an eye on feminisms, as well as global politics of conflict and disaster recovery in South and Southeast Asia. -

District Secretariat - Matara

කායය සාධන වාතාව සහ - 2012 ெசயதிற அறிைக, கண - 2012 Performance Report & Accounts - 2012 ස් ෙක කායාලය - මාතර மாவட ெசயலக - மாதைற District Secretariat - Matara Content 1 Message of the District Secretary 1 2. Introduction of the District Secretariat 2-3 3 Introduction of the District 4-15 4 Organizational Structure and Approved Cadre 15-17 5 Performance – Comparison with action plan 18-57 5.1 Progress of General Administration Activities 18-26 5.2 Progress of Social Servicers and Cultural 27-31 5.3 Progress of Development Activities 31-47 5.4 Annual Accounts 48-57 0 Performance Report and Accounts of District Secretariat of Matara for the year 2012 1. Message from District Secretary As the guardian of the district, it is my responsibility to plan and implement policies needed for the development of Matara district and obtain utmost benefits through that process. I highly appreciate this opportunity in issuing a message for this report by which the standard of the service provided to the general public is measured and targets of service planning expected to be achieve in the year 2013. State policies have featured that most of services provided by the government in order to upgrade the living standard of the low income families are provided and many development projects are carried out through District Secretariat and Divisional Secretariats. Public trust will be ensured by publishing details of performance of these activities and services and people contribution to the development process could be promoted. According to the annual budget, in the process of utilizing financial resources allocated within the year 2012, performance of financial operations of District Secretariat, 16 Divisional Secretariats, 650 Grama Niladari divisions and line ministries including Economic Development and Disaster Management is included in this report. -

!"#$"%&'()%!*"+(#,%-&./"#0%/!- Annual Report 2015/16

!"#$"%&'()%!*"+(#,%-&./"#0%/!- Annual Report 2015/16 What we have achieved together Our business interests are wide ranging, generating employment in a diversity of industry sectors including financial services, agriculture and plantations, energy, leisure, construction, manufacturing and trading. Our operations also impact the lives of thousands of people every day, through our micro-finance and SME services that have empowered Sri Lankans islandwide. Our strategic alliances with several reputed global lending agencies strengthen our offering, as we expand our footprint across the region. The year under review was an outstanding one and we are proud to deliver these fine results to our loyal stakeholders, as together we imagine the possibilities for value creation that we can explore in the years that lie ahead. LANKA ORIX LEASING COMPANY PLC Annual Report 2015/16 Group Overview / Operational Information / Governance / Financial Information / Supplementary Information Contents Group Overview Financial Information About Us 3 Financial Calendar 130 Sector Overview 4 Chief Executive Officer’s and Chief Financial A Compelling Investment Proposition 8 Officer’s Responsibility Statement 131 Our Presence 10 Directors’ Responsibility for Financial Reporting 132 Group Structure 12 Independent Auditors’ Report 133 Funding Partners 14 Statement of Financial Position 134 The ORIX Connection 17 Statement of Profit or Loss 136 Financial Highlights 18 Statement of Comprehensive Income 137 Awards and Certifications 20 Statement of Changes in Equity 138 -

Cultivated Tastes Colonial Art, Nature and Landscape in The

F Cultivated Tastes G Colonial Art, Nature and Landscape in the Netherlands Indies A Doctoral Dissertation by Susie Protschky PhD Candidate School of History University of New South Wales Sydney, Australia Contents Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………….. iii List of Abbreviations ………………………………………………………….. v List of Plates …………………………………………………………………… vi F G Introduction ……………………………………………………………………. 1 Part I — Two Journeys Chapter 1: Landscape in Indonesian Art ……………………………………….. 36 Chapter 2: Dutch Views of Indies Landscapes …………………………………. 77 Part II — Ideals Chapter 3: Order ………………………………………………………………. 119 Chapter 4: Peace ………………………………………………………………. 162 Chapter 5: Sacred Landscapes ………………………………………………… 201 Part III — Anxieties Chapter 6: Seductions …………………………………………………………. 228 Chapter 7: Identity – Being Dutch in the Tropics …………………………….. 252 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………….. 293 F G Glossary ……………………………………………………………………….. 319 Bibliography …………………………………………………………………... 322 ii Acknowledgments First, I would like to express my gratitude to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of New South Wales for granting me an Australian Postgraduate Award between 2001 and 2005. The same Faculty funded two research trips abroad, one to the Netherlands in 2004 and another to Indonesia in 2005. Without these sources of funding this thesis would not have possible. In the Netherlands, I must thank Pim Westerkamp at the Museum Nusantara, Delft, for taking me on a tour through the collection and making archival materials available to me. Thanks also to Marie-Odette Scalliet at the University of Leiden, for directing me toward more of her research and for showing me some of the university library’s Southeast Asia collection. I also appreciate the generosity of Peter Boomgaard, of the KITLV in Leiden, for discussing aspects of my research with me. Thanks to the staff at the KIT Fotobureau in Amsterdam, who responded admirably to my vague request for ‘landscape’ photographs from the Netherlands Indies. -

5000-Schools-Funded-By-The-Ministry

5000 Schools developed as Child Frendly Schools by funding Rs 500,000.00 by Economic Development Ministry to develop infastructure Province District Name of School Address Education Zone Education Division 1 Western Colombo SRI SANGAMITTA P.V. 62,ANANDA RAJAKARUNA MW.,COL-09 Colombo Borella 2 Western Colombo SUJATHA B.V. KIRIMANDALA MW.,COL-05 Colombo Colombo - South 3 Western Colombo LUMBINI P.V. HAVELOCK TOWN,COL-05. Colombo Colombo - South 4 Western Colombo ST.CLARE'S B.M.V. 1SR CHAPEL LANE,COL-06. Colombo Colombo - South 5 Western Colombo THANNINAYAGAM T.V. LESLEY RANAGALA MW.,COL-08 Colombo Borella 6 Western Colombo SIR BARON JAYATHILAKA V. MALIGAWATTA,COL-10. Colombo Colombo - Central 7 Western Colombo MIHINDU MAWATHA SINHALA V. MIHINDU MAWATHA,COLOMBO 12. Colombo Colombo - Central 8 Western Colombo ROMAN CATHOLIC V. KOTIKAWATTA, MULLERIYAWA NEW TOWN. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 9 Western Colombo MEETHOTAMULLA SRI RAHULA V. MEETHOTAMULLA, KOLONNAWA. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 10 Western Colombo KOTUWILA GAMINI V. KOTUWILA, WELLAMPITIYA. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 11 Western Colombo WERAGODA K.V. KOLONNAWA, WELLAMPITIYA. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 12 Western Colombo GOTHATUWA M.V. GOTHATUWA, ANGODA. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 13 Western Colombo VIDYAWARDENA V. WELLAMPITIYA, KOLONNAWA. Sri Jaya' pura Kolonnawa 14 Western Colombo SUGATHADHARMADHARA V. EGODAUYANA, MORATUWA Piliyandala Moratuwa 15 Western Colombo KATUKURUNDA ST MARY'S V. KATUKURUNDA, MORATUWA Piliyandala Moratuwa 16 Western Colombo SRI SADDARMODAYA V. KORALAWELLA MORATUWA Piliyandala Moratuwa 17 Western Colombo SRI NAGASENA V. KORAWELLA, MORATUWA Piliyandala Moratuwa 18 Western Colombo PITIPANA K.V. PITIPANA NORTH, HOMAGAMA. Homagama Homagama 19 Western Colombo DOLAHENA K.V. -

Region Kabupaten Kecamatan Kelurahan Alamat Agen Agen Id Nama Agen Pic Agen Jaringan Kantor

REGION KABUPATEN KECAMATAN KELURAHAN ALAMAT AGEN AGEN ID NAMA AGEN PIC AGEN JARINGAN_KANTOR NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEEH UTARA DEWANTARA ULEE PULO GAMPONG ULEE PULO 213IB0107P000076 INDI CELL INDIRA MAYA RISWADANA PENSION LHOKSEUMAWE NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEEH UTARA SEUNUDDON ALUE CAPLI DUSUN MATANG ARON 213IB0115P000048 DUA PUTRA MANDIRI RATNA JELITA PENSION LHOKSEUMAWE NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEH BESAR BAITUSSALAM BAET DUSUN KRUENG CUT 213IA0115P000031 KIOS NASI IBU BETA SURYANI PENSION BANDA ACEH NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEH BESAR BAITUSSALAM BAET JL LAKSAMANA MALAHAYATI 213IA0115P000039 KIOS WARKOP PAYONG 1903 HERI DARMANSYAH PENSION BANDA ACEH NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEH BESAR BAITUSSALAM BAET JL LAKSAMANA MALAHAYATI 213IA0115P005130 MOCHY CELL ERNI PENSION BANDA ACEH NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEH BESAR BAITUSSALAM BAET JL LAKSAMANA MALAHAYATI 213IA0115P010046 KIOS ARRAHMAN ARAHMAN KAUNUS PENSION BANDA ACEH NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEH BESAR BAITUSSALAM BAET JL LAKSAMANA MALAHAYATI 213IA0115P000026 KIOS ZAIMAN ZAIMAN NURDIN S.PT PENSION BANDA ACEH NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEH BESAR BAITUSSALAM CADEK JL LAKSAMANA MALAHAYATI 213IA0115P010008 ARITA NEW STEEL MASRI PENSION BANDA ACEH NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEH BESAR BAITUSSALAM CADEK JL LAKSAMANA MALAHAYATI 213IA0115P005091 USAHA HIJRAH SYAIF ANNUR PENSION BANDA ACEH NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEH BESAR BAITUSSALAM CADEK JL MALAHAYATI 213IA0115P005080 USAHA BARU T ISKANDAR PENSION BANDA ACEH NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEH BESAR BAITUSSALAM CADEK JL. LAKSAMANA MALAHAYATI 213IA0115P000004 PUTRA MAMA ANWARDI PENSION BANDA ACEH NORTHERN SUMATERA ACEH -

The Emergence of Movie-Going in Colonial Indonesia, 1896-1914

THE KOMEDI BIOSCOOP: The Emergence of Movie-going in Colonial Indonesia, 1896-1914 DE KOMEDI BIOSCOOP: De opkomst van de filmcultuur in koloniaal Indonesië, 1896-1914 (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 29 april 2015 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door Dafna Ruppin geboren op 30 november 1980 te Tel Aviv, Israel i Promotor: Prof. dr. F. E. Kessler Copromoter: Dr. A. van der Velden This thesis was accomplished with financial support from the NWO program “Cultural Dynamics”. ii iii Figure I. Map of the Netherlands Indies , c. 1893, showing railway lines and steamship connections iv Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin (source: http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/nederlandsch_indie_1893.jpg) v vi Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................... vii List of figures ..................................................................................................................................... xi Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... xiii Glossary .......................................................................................................................................... -

Download Fact Sheet

ENSELLWATTA ESTATE, VIHARAHENA, DENIYAYA. SRI LANKA Head Office Reservations: +94766900900 E. [email protected] Hotel Inquiries: +94 41 4546010 / 0766919243 W. www.rainforest-ecolodge.com Introduction Step into the wilderness where time stands still in eternal moments of sheer bliss, where nature and man make a merger of the most spectacular kind. Discover the Sinharaja rainforest, the only natural UNESCO World Heritage Site in the country whose diverse culture of exquisite flora and fauna pave the way for an enchanting experience. Feel at home within 20 comfortable chalets that are designed with recycled material and adorned with every amenity imaginable. An unparalleled level of sustainability has been reached by incorporating the best practices in the spheres of planning, construction and operations. Awarded the 'LEEDS PLATINUM for Sustainable Tourism' through Eco Management, The Rainforest, Deniyaya, Sri Lanka is proud to be the 1st in Sri Lanka, 5th in the world and 4th in Asia to be crowned with this rare honour. IFC, a member of the World Bank Group, provided advisory assistance and USAID supported the initiative. The hotel consists of 20 Eco Chalets which includes comfortable cosy bedroom, a washroom, a living area and a private deck. The Main building houses the restaurant, kitchen, the lounge and the bar, interpretation Centre and the deck adjoining. The lounge provides a beautiful view of the tea patch and the forest around it. Its cosy interior is an ideal place to snuggle in when the rain characteristic to the area pours on. Location The closest town to the Rainforest Ecolodge is Deniyaya, which can be reached from Colombo / Bandaranaike International Airport via following routes. -

PUBLIC Dehiattakandiya M/B 027-577-6253 NO

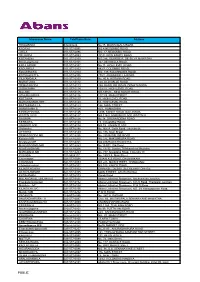

Showroom Name TelePhone Num Address HINGURANA 632240228 No.15, MUWANGALA ROAD. KADANA 011-577-6095 NO.4 NEGOMBO ROAD JAELA 011-577-6096 NO. 17, NEGOMBO ROAD DELGODA 011-577-6099 351/F, NEW KANDY ROAD KOTAHENA 011-577-6100 NO:286, GEORGE R. DE SILVA MAWATHA Boralesgamuwa 011-577-6101 227, DEHIWALA ROAD, KIRULAPONE 011-577-6102 No 11, HIGH LEVEL ROAD, KADUWELA 011-577-6103 482/7, COLOMBO ROAD, KOLONNAWA 011-577-6104 NO. 139, KOLONNAWA ROAD, KOTIKAWATTA 011-577-6105 275/2, AVISSAWELLA ROAD, PILIYANDALA 011-577-6109 No. 40 A, HORANA ROAD , MORATUWA 011-577-6112 120, OLD GALLE ROAD, DEMATAGODA 011-577-6113 394, BASELINE ROAD, DEMATAGODA, GODAGAMA 011-577-6114 159/2/1, HIGH LEVEL ROAD. MALABE 011-577-6115 NO.837/2C , NEW KANDY ROAD, ATHURUGIRIYA 011-577-6116 117/1/5, MAIN STREET, KOTTAWA 011-577-6117 91, HIGH LEVEL ROAD, MAHARAGAMA RET 011-577-6120 63, HIGH LEVEL ROAD, BATTARAMULLA 011-577-6123 146, MAIN STREET, HOMAGAMA B 011-577-6124 42/1, HOMAGAMA KIRIBATHGODA 011-577-6125 140B, KANDY ROAD, DALUGAMA, WATTALAJVC 011-577-6127 NO.114/A,GAMUNU PLACE,WATTALA RAGAMA 011-577-6128 No.18, SIRIWARDENA ROAD KESBAWA 011-577-6130 19, COLOMBO ROAD, UNION PLACE 011-577-6134 NO 19 , UNION PLACE Wellwatha 011-577-6148 No. 506 A, Galle Road, colombo 06 ATTIDIYA 011-577-6149 No. 186, Main Street, DEMATAGODA MB 011-577-6255 No. 255 BASELINE ROAD Kottawa M/B 011-577-6260 NO.375, MAKUMBURA ROAD, Moratuwa M/B 011-577-6261 NO.486,RAWATHAWATTA MAHARAGAMA M/B 011-577-6263 No:153/01, Old Road, NUGEGODA MB 011-577-6266 No. -

Draft Sri Lanka National Factsheet

Best Practice in Small-scale Gemstone Mining DFID Knowledge and Research Project DRAFT SRI LANKA NATIONAL FACTSHEET 1999 Sri Lanka National Factsheet Disclaimer This project is an output from a project (R7115) funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the DFID. Author: Dr Paul Henney, British Geological Survey (BGS), UK Project Manager – Heather Mackay Intermediate Technology Consultants (ITC) Ltd Bourton Hall Bourton-on-Dunsmore Rugby, CV23 9QZ United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)1926 634403 Fax: +44 (0)1926 634405 Email: [email protected] Web: www.itcltd.com 1 Sri Lanka National Factsheet Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................1 1. PURPOSE OF THE RESEARCH AND FACTSHEET ..........................6 2. BACKGROUND....................................................................................7 2.1 The Small Scale Mining Industry......................................................................7 2.2 Mine Owners ....................................................................................................7 2.3 Mine Workers ...................................................................................................8 3. GEOLOGY..........................................................................................10 4. OPERATIONAL PRACTICES ............................................................13 4.1 Prospecting and Exploration ..........................................................................13 -

Census Codes of Administrative Units Southern Province Sri Lanka Province District DS Division GN Division Name Code Name Code Name Code Name No

Census Codes of Administrative Units Southern Province Sri Lanka Province District DS Division GN Division Name Code Name Code Name Code Name No. Code Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Pahurumulla 1 005 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Sinharoopagama 3B 010 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Yathramulla 3 015 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Kommala 3C 020 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Bodhimaluwa 3A 025 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Dope 5 030 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Angagoda 2 035 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Warahena 2A 040 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Kahagalla 5A 045 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Hunganthota Wadumulla 3D 050 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Dedduwa 6 055 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Athuruwella 8C 060 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Galbada 8A 065 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Galagama 11C 070 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Mullegoda 11A 075 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Sooriyagama 12D 080 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Haburugala 12 085 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Thunduwa West 12C 090 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Thunduwa East 12B 095 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Thotakanatta 12A 100 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Elakaka 12E 105 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Ethungagoda 14E 110 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Gonagalapura 11 115 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Olaganduwa 8B 120 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Yalegama 8 125 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Kaikawala 9 130 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Habakkala 9C 135 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 Etawalawatta West 9B 140 Southern 3 Galle 1 Benthota 03 -

Post-Disaster Recovery Plan and Recovery Framework 17

Post-Disaster Ministry of National Policies and Economic Affairs Ministry of Disaster Management Recovery Plan Public Disclosure Authorized SRI LANKA, FLOODS AND LANDSLIDES MAY 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CONTENTS Acknowledgments 5 Foreward 7 List of Figures and Tables 9 Acronyms 11 1. Background and Context 13 1.1 Overview of the Post-Disaster Needs Assessments (PDNAs) 2016 and 2017 15 1.2 Recovery Needs 16 1.3 Post-Disaster Recovery Plan and Recovery Framework 17 2. Purpose of the Post-Disaster Recovery Plan 19 3. Recovery Vision, Objectives and Guiding Principals 23 4. Current status of Recovery 27 4.1. Funds Already Allocated Against Recovery and Status of Work that Commenced 29 4.2 Status of Work Commenced and the Implementation Process 30 5. Policy framework/Guideline 33 5.1 Policy Recommendations for Recovery from Floods and Landslides 35 5.2 Vision 2025 and Post-Disaster Recovery 38 6. Institutional Arrangements for Recovery 41 6.1 Role of NPD, MoDM, and Line Ministries 43 6.2 Role of District Secretaries 47 6.3 Role of Provincial Councils and Local Government Institutes 47 7. Implementation Arrangements for Recovery 49 7.1 Implementation Arrangements by sector of intervention 51 7.2 Role of Districts Secretaries and Divisional Secretaries 54 7.3 Role of Provincial Government Authorities 54 7.4 Role of Development Partners, NGOs and Civil Society 54 7.5 Strengthening Implementation Capacity 55 7.6 Constraints and Challenges in Recovery 55 7.7 Monitoring and Transparency 56 7.8 Integrating Gender in Recovery 56 3 8.