The Seagull by Anton Chekhov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Aesthetic Terrain of Settler Colonialism: Katherine Mansfield and Anton Chekhov’S Natives

Journal of Postcolonial Writing ISSN: 1744-9855 (Print) 1744-9863 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjpw20 The aesthetic terrain of settler colonialism: Katherine Mansfield and Anton Chekhov’s natives Rebecca Ruth Gould To cite this article: Rebecca Ruth Gould (2018): The aesthetic terrain of settler colonialism: Katherine Mansfield and Anton Chekhov’s natives, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, DOI: 10.1080/17449855.2018.1511242 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17449855.2018.1511242 Published online: 04 Oct 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjpw20 JOURNAL OF POSTCOLONIAL WRITING https://doi.org/10.1080/17449855.2018.1511242 The aesthetic terrain of settler colonialism: Katherine Mansfield and Anton Chekhov’snatives Rebecca Ruth Gould College of Arts and Law, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS While Anton Chekhov’sinfluence on Katherine Mansfield is Settler colonialism; Sakhalin; widely acknowledged, the two writers’ settler colonial aesthetics New Zealand; Siberia; Maori; have not been brought into systematic comparison. Yet Gilyak; Russian Empire Chekhov’s chronicle of Sakhalin Island in the Russian Far East parallels in important ways Mansfield’s near-contemporaneous account of colonial life in New Zealand. Both writers are con- cerned with a specific variant of the colonial situation: settler colonialism, which prioritizes appropriation of land over the gov- ernance of peoples. This article considers the aesthetic strategies each writer develops for capturing that milieu within the frame- work of the settler colonial aesthetics that has guided much anthropological engagement with endangered peoples. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

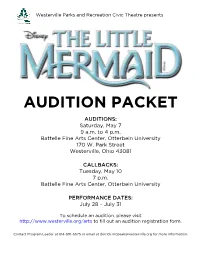

Audition Packet

Westerville Parks and Recreation Civic Theatre presents AUDITION PACKET AUDITIONS: Saturday, May 7 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Battelle Fine Arts Center, Otterbein University 170 W. Park Street Westerville, Ohio 43081 CALLBACKS: Tuesday, May 10 7 p.m. Battelle Fine Arts Center, Otterbein University PERFORMANCE DATES: July 28 – July 31 To schedule an audition, please visit http://www.westerville.org/arts to fill out an audition registration form. Contact Program Leader at 614-901-6575 or email at [email protected] for more information. AUDITION INFORMATION WHEN: Saturday, May 7, 9 a.m. - 4 p.m.; Auditions are made by appointment WHERE: Battelle Fine Arts Center, Otterbein University, 170 W Park Street, Westerville, OH 43081. HOW TO REGISTER: Please visit and click on the audition registration link. This will take you to a form where you may enter your information and preferred time of audition. You will receive a confirmation email/phone call of your audition within two business days. WHO: We welcome auditions for people of all ages! Children must be 7 years old at the time of audition. COST: For actors, singers, and dancers: $125 for children ages 7-12, $75 for adults and youth 13+. Scholarships and payment plans are available for those in need of financial assistance. HOW TO AUDITION: Groups of 10-15 performers will sing, dance, and read if needed in one hour blocks. You may audition for a specific role or for the ensemble. The dance audition will be movement based. No formal dance training is necessary. Please prepare 16 -32 bars of any musical theatre song (enough to cover one verse and one chorus). -

O MAGIC LAKE Чайкаthe ENVIRONMENT of the SEAGULL the DACHA Дать Dat to Give

“Twilight Moon” by Isaak Levitan, 1898 O MAGIC LAKE чайкаTHE ENVIRONMENT OF THE SEAGULL THE DACHA дать dat to give DEFINITION датьA seasonal or year-round home in “Russian Dacha or Summer House” by Karl Ivanovich Russia. Ranging from shacks to cottages Kollman,1834 to villas, dachas have reflected changes in property ownership throughout Russian history. In 1894, the year Chekhov wrote The Seagull, dachas were more commonly owned by the “new rich” than ever before. The characters in The Seagull more likely represent the class of the intelligencia: artists, authors, and actors. FUN FACTS Dachas have strong connections with nature, bringing farming and gardening to city folk. A higher class Russian vacation home or estate was called a Usad’ba. Dachas were often associated with adultery and debauchery. 1 HISTORYистория & ARCHITECTURE история istoria history дать HISTORY The term “dacha” originally referred to “The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” by the land given to civil servants and war Alphonse Mucha heroes by the tsar. In 1861, Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia, and the middle class was able to purchase dwellings built on dachas. These people were called dachniki. Chekhov ridiculed dashniki. ARCHITECTURE Neoclassicism represented intelligence An example of 19th century and culture, so aristocrats of this time neoclassical architecture attempted to reflect this in their architecture. Features of neoclassical architecture include geometric forms, simplicity in structure, grand scales, dramatic use of Greek columns, Roman details, and French windows. Sorin’s estate includes French windows, and likely other elements of neoclassical style. Chekhov’s White Dacha in Melikhovo, 1893 МéлиховоMELIKHOVO Мéлихово Meleekhovo Chekhov’s estate WHITE Chekhov’s house was called “The White DACHA Dacha” and was on the Melikhovo estate. -

A Tale of Two Birds: Lighting Design and Implementation of Anton Chekhov's the Seagull and Aaron Posner's Stupid Fucking

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 3-23-2018 A Tale of Two Birds: Lighting Design and Implementation of Anton Chekhov's The eS agull and Aaron Posner's Stupid Fucking Bird Running in Repertory at Swine Palace Theatre Chelsea G. Touchet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Touchet, Chelsea G., "A Tale of Two Birds: Lighting Design and Implementation of Anton Chekhov's The eS agull and Aaron Posner's Stupid Fucking Bird Running in Repertory at Swine Palace Theatre" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4632. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4632 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A TALE OF TWO BIRDS: LIGHTING DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION OF ANTON CHEKHOV’S THE SEAGULL AND AARON POSNER’S STUPID FUCKING BIRD RUNNING IN REPERTORY AT SWINE PALACE THEATRE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and College of Music and Dramatic Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The School of Theatre by Chelsea Gabrielle Touchet B.S., University of Evansville, 2011 May 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people contributed to the success and completion of these two productions. -

Title Link – Story in English Link – Story in Russian Link – Other

לק"י Title Link – story in English Link – story in Russian Link – other http://chekhov2.tripod.com/035.htm http://bibliotekar.ru/rusChehov/71.ht http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1732/1732-h/1732- m h.htm#link2H_4_0006 In a Strange Land http://www.online- http://chehov.niv.ru/chehov/text/na- literature.com/anton_chekhov/1136/ chuzhbine.htm http://www.online-literature.com/donne/1136/ http://chekhov2.tripod.com/023.htm http://chehov.niv.ru/chehov/text/v- In an Hotel http://www.online- nomerah.htm literature.com/anton_chekhov/1124/ http://www.online- literature.com/anton_chekhov/1264/ http://chehov.niv.ru/chehov/text/v- In Exile http://chekhov2.tripod.com/164.htm ssylke.htm http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/In_Exile http://www.lib.ru/LITRA/CHEHOW/r_c http://chekhov2.tripod.com/113.htm h_week.txt In Passion Week http://www.online- http://chehov.niv.ru/chehov/text/na- literature.com/anton_chekhov/1214/ strastnoj-nedele.htm http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/In_Passion_Week http://chehov.niv.ru/chehov/text/vesn oj.htm http://chehov.niv.ru/chehov/text/vesn In spring oj_1.htm http://www.lib.ru/LITRA/CHEHOW/ves na.txt http://www.lib.ru/LITRA/CHEHOW/vag In the Carriage / In the Wagon on.txt http://chekhov2.tripod.com/129.htm http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1732/1732-h/1732- http://chehov.niv.ru/chehov/text/v- In the Coach - House h.htm#link2H_4_0015 sarae.htm http://www.online- literature.com/anton_chekhov/1230/ http://www.online- http://chehov.niv.ru/chehov/text/v- In the Court literature.com/anton_chekhov/1186/ sude.htm http://chekhov2.tripod.com/085.htm -

Ballet Notes the Seagull March 21 – 25, 2012

Ballet Notes The SeagUll March 21 – 25, 2012 Aleksandar Antonijevic and Sonia Rodriguez as Trigorin and Nina. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann. Orchestra Violins Trumpets Benjamin Bowman Richard Sandals, Principal Concertmaster Mark Dharmaratnam Lynn KUo, Robert WeymoUth Assistant Concertmaster Trombones DominiqUe Laplante, David Archer, Principal Principal Second Violin Robert FergUson James Aylesworth David Pell, Bass Trombone Jennie Baccante Csaba Ko czó Tuba Sheldon Grabke Sasha Johnson, Principal Xiao Grabke • Nancy Kershaw Harp Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk LUcie Parent, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., FoUnder Yakov Lerner Timpany George Crum, MUsic Director EmeritUs Jayne Maddison Michael Perry, Principal Ron Mah Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Aya Miyagawa Percussion Mark MazUr, Acting Artistic Director ExecUtive Director Wendy Rogers Filip Tomov Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Joanna Zabrowarna Kristofer Maddigan MUsic Director and Artist-in-Residence PaUl ZevenhUizen Orchestra Personnel Principal CondUctor Violas Manager and Music Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Angela RUdden, Principal Administrator Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, • Theresa RUdolph Koczó, Jean Verch YOU dance / Ballet Master Assistant Principal Assistant Orchestra Valerie KUinka Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne Personnel Manager Johann Lotter Raymond Tizzard Senior Ballet Master Richardson Beverley Spotton Senior Ballet Mistress • Larry Toman Librarian LUcie Parent Aleksandar Antonijevic, GUillaUme Côté, Cellos Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, Zdenek Konvalina*, -

The Seagull Reader: Literature Literature 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE SEAGULL READER: LITERATURE LITERATURE 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joseph Kelly | 9780393926774 | | | | | The Seagull Reader: Literature Literature 1st edition PDF Book This comprehensive Seagull Reader: Literature reader includes the full contents of the three separate Seagull Reader: Plays, Poems, and Stories readers, in one portable volume. Available online at Project Gutenberg. Wikimedia Commons. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. The play was also adapted as the Russian film The Seagull in Act I also sets up the play's various romantic triangles. Between acts Konstantin attempted suicide by shooting himself in the head, but the bullet only grazed his skull. Despondent, Konstantin spends two minutes silently tearing up his manuscripts before leaving the study. Anton Chekhov 's The Seagull Trigorin leaves to continue packing. He returns and takes Trigorin aside. Brooks rated it really liked it Jul 06, It also featured Chiwetel Ejiofor and Art Malik. Untamed by Glennon Doyle. After she has left the room, Nina comes to say her final goodbye to Trigorin and to inform him that she is running away to become an actress, against her parents' wishes. For teachers who wants to have a solid collection at their disposal, I would recommend looking into this book. Alexandrinsky Theatre , St. I am writing it not without pleasure, though I swear fearfully at the conventions of the stage. Chekhov's unwillingness to explain or expand on the script forced Stanislavski to dig beneath the surface of the text in ways that were new in theatre. The Independent. Readers also enjoyed. -

Theatre and the Family: Anton Chekhov, 'The Cherry Orchard' Transcript

Theatre and The Family: Anton Chekhov, 'The Cherry Orchard' Transcript Date: Tuesday, 23 February 2016 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 23 February 2016 Theatre and The Family: Anton Chekhov, The Cherry Orchard Professor Belinda Jack Music – Tchaikovsky - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ABGZhFsXYI; Four Seasons, April/Spring (Vladimir Ashkenazy) Good evening and welcome – and thank you for coming. Particularly good to see some familiar faces from previous lectures and particularly my last lecture on Ibsen's A Doll's House as this evening's lecture is something of a companion piece. This extraordinary play poses two particularly intriguing questions. The first is this: how does it hold our attention given the limited amount of action? And the second: is it really a comedy as the playwright himself insisted it was? Jean-Louis Barrault, the French actor and director, summarizes the action of The Cherry Orchard in the following way: 'In Act One, the cherry orchard is in danger of being sold, in Act Two it is on the verge of being sold, in Act Three it is sold, and in Act Four it has been sold' (Laurence Senelick Anton Chekhov, 1985, 124-25) Thus described the play seems devoid of dramatic action. The felling of the Orchard, which is arguably the dramatic climax of the play, takes place off-stage. We only hear the axe as it meets the trunk of the first cherry tree. How could the scenario described by Barrault be construed as 'comic'? Many of you will know the play but in case some of you do not, this is a slightly fuller description than Barrault's. -

Philip Stoddard [email protected]

Philip Stoddard [email protected] THE JUILLIARD SCHOOL FATHER COMES HOME FROM THE WARS Colonel LA Williams P.Y.G. Dorian Belle Tearrance Chisholm THE TRIUMPH OF LOVE Agis Stephen Wadsworth TROJAN WOMEN Poseidon Ellen Lauren CYMBELINE Cloten Jenny Lord GETTING OUT Carl/Guard Evans Oliver Butler WOYZECK Woyzeck Stephanie Mareen KING LEAR King Lear Richard Feldman A MUSICAL EVENING OF CABARET Soloist Deborah Lapidus HENRY V Canterbury/ Rebecca Guy French King/Bates THE ADDING MACHINE Ensemble Moni Yakim THE SEAGULL Dr. Dorn Brian McManamon BALM IN GILEAD Franny/Stranger Rebecca Guy THE SAMUEL BECKETT PROJECT Tommy/Fox Jesse J. Perez DARK OF THE MOON Marvin Hudgens Trazana Beverley ALL MY SONS Dr. Jim Bayliss Jenny Lord ALL’S WELL THAT ENDS WELL Bertram/Lafew/ Sarah Grace Wilson 2nd Lord A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC Mr. Lindquist Claire Karpen OTHER THEATER THE ROMEO+JULIET PROJECT Prince Escalus Vivienne Benesch Chautauqua Theater Company BRIGADOON Tommy Albright John Giampietro Chautauqua Music Festival DON GIOVANNI Don Giovanni John Giampietro RELATED EXPERIENCE NARCISSUS (upcoming) Director/Co-Creator Satellite Collective @ BAM OPERA-COMP Co-Artistic Director/ The Juilliard School Producer OPERATION SUPERPOWER! Co-Creator/Performer Tri-State Area Public Schools SKILLS Award winning singer (classically trained baritone/musical theater bari-tenor), Teaching Artist, Italian (conversational), Beginner Piano and Accordion, Three-ball juggling, Yoga EDUCATION The Juilliard School Drama Division The Juilliard School Marcus Institute for Vocal Arts . -

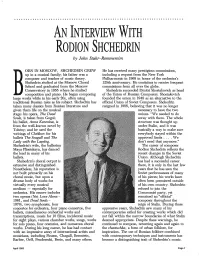

AN INTERVIEW with RODION SHCHEDRIN by John Stuhr-Rommereim

· ........................................................................ AN INTERVIEW WITH RODION SHCHEDRIN by John Stuhr-Rommereim ORN IN MOSCOW, SHCHEDRIN GREW He has received many prestigious commissions, up in a musical family; his father was a including a request from the New York composer and teacher of music theory. Philharmonic in 1968 in honor of the orchestra's Shchedrin studied at the Moscow Choral 125th anniversary. He continues to receive frequent School and graduated from the Moscow commissions from all over the globe. Conservatory in 1955 where he studied Shchedrin succeeded Dmitri Shostakovich as head composition and piano. He began composing of the Union of Russian Composers. Shostakovich large works while in his early 20s, often using founded the union in 1948 as an alternative to the traditional Russian tales as his subject. Shchedrin has official Union of Soviet Composers. Shchedrin taken many classics from Russian literature and resigned in 1988, believing that it was no longer given them life on the musical necessary to have the two stage: his opera, The Dead unions. "We needed to do Souls, is taken from Gogol; away with them. The whole his ballet, Anna Karenina, is structure was thought up from the well-known novel by under Stalin, and it was Tolstoy; and he used the basically a way to make sure writings of Chekhov for his everybody stayed within the ballets The Seagull and The approved limits . We Lady with the Lapdog. don't need that anymore." Shchedrin's wife, the ballerina The career of composer Maya Plisetskaya, has danced Rodion Shchedrin reflects the the lead in many of his recent changes in the Soviet ballets. -

The Sea Gull Is Set in Russia in 1893

The School of Theatre’s production of The Sea Gull is set in Russia in 1893. Growing up Chekhov Anton Pavlovich Chekhov was born on Find out what was happening around the world at the time! January 17, 1860 in Taganrog, a small town in the Sea of Azov in southern Russia. His April 8 - The first recorded college basketball game occurs father led a strict household, with the in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania between the Geneva College children’s time divided among school, Covenanters and the New Brighton YMCA. working in his grocery store, and strict daily observance of Russian Orthodox Church May 5 - Panic of 1893: The New York Stock Exchange worship. crashed, leading to an economic depression in America. The Chekhov attended school at the local Depression of 1893 was one of the worst in American history with the gymnazija (which is a government middle and high school). When his father’s unemployment rate exceeding ten percent for half a decade. grocery store business failed, his family moved to Moscow, leaving Anton behind to finish school. He supported himself for July 1 - U.S. President Grover Cleveland is secretly oper- several years by tutoring other students. ated on to avoid further panic that might worsen the financial In 1879 Anton joined his family in Russia depression. Under the guise of a vacation cruise, Dr. Joseph Did you know? and enrolled in Medical School at Moscow Bryant removed parts of his upper left jaw and hard palate. The The Russian name of the play actually translates into State University.