APPENDIX 1. DESCRIPTION, LITERATURE, and RECENSIONS Murvarid’S Preface to the Album for Mir #Ali Shir Nava"I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Patna's Drawings” Album

Mughal miniatures share these basic characteristics, but they also incorporate interesting innovations. Many of these deviations results from the fact that European prints and art objects had been available in India since the establishment of new trading colonies along the western coast in the sixteenth century. Mughal artists thus added to traditional Persian and Islamic forms by including European techniques such as shading and at- mospheric perspective. It is interesting to note that Eu- ropean artists were likewise interested in Mughal paint- ing—the Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn collected and copied such works, as did later artists such as Sir Joshua Reynolds and William Morris. These images continued to interest westerners in the Victorian era, during the period of Art Nouveau, and even today. [For a demon- stration of Persian miniature painting, see http://vimeo. com/35276945.] The DepicTion of The RuleR in Mughal MiniaTuRe painTing While Humayun was largely responsible for the im- portation of Persian painters to India, it was under Ak- bar that Mughal miniature painting first truly flourished. Akbar maintained an imperial studio where more than a hundred artists illustrated classical Persian literary texts, as well as the Mahabharata, the great Hindu epic that the emperor had translated into Persian from its original Sanskrit. Akbar also sponsored various books describing his own good deeds and those of his ancestors. Such books were expansive—some were five hundred pages long, with more than a hundred miniature paintings illustrat- portrait of the emperor shahjahan, enthroned, ing the text. It is here that we see the first concentrated from the “patna’s Drawings” album. -

Islamic Art Pp001-025 21/5/07 08:53 Page 2

Spirit &Life Spirit & Life The creation of a museum dedicated to the presentation of Muslim ‘I have been involved in the field of development for nearly four decades. arts and culture – in all their historic, cultural and geographical Masterpieces of Islamic Art This engagement has been grounded in my responsibilities as Imam of diversity – is a key project of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, one the Shia Ismaili Community, and Islam’s message of the fundamental of whose aims is to contribute to education in the fields of arts and from the Aga Khan Museum Collection unity of “din and dunya”, of spirit and life.’ culture. The developing political crises of the last few years have collections museum khan theaga from art ofislamic masterpieces revealed – often dramatically – the considerable lack of knowledge of His Highness the Aga Khan the Muslim world in many Western societies. This ignorance spans at the Annual Meeting of the EBRD all aspects of Islam: its pluralism, the diversity of interpretations Tashkent, 5 May 2003 within the Qur’anic faith, the chronological and geographical extent of its history and culture, as well as the ethnic, linguistic and social Spirit and Life is the title of an exhibition of over 160 masterpieces diversity of its peoples. of Islamic art from the Aga Khan Museum which will open in Toronto, Canada in 2009. This catalogue illustrates all the miniature For this reason, the idea of creating a museum of Muslim arts and paintings, manuscripts, jewellery, ceramics, wood panels and culture in Toronto as an eminently educational institution, with beams, stone carvings, metal objects and other art works in the the aim of informing the North American public of the diversity and exhibition, which spans over a thousand years of history and gives significance of Muslim civilisations naturally arose. -

Studies and Sources in Islamic Art and Architecture

STUDIES AND SOURCES IN ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE SUPPLEMENTS TO MUQARNAS Sponsored by the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts. VOLUME IX PREFACING THE IMAGE THE WRITING OF ART HISTORY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY IRAN BY DAVID J. ROXBURGH BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2001 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roxburgh, David J. Prefacing the image : the writing of art history in sixteenth-century Iran / David J. Roxburgh. p. cm. — (Studies and sources in Islamic art and architecture. Supplements to Muqarnas, ISSN 0921 0326 ; v. 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9004113762 (alk. papier) 1. Art, Safavid—Historiography—Sources. 2. Art, Islamic—Iran– –Historiography—Sources. 3. Art criticism—Iran—History—Sources. I. Title. II. Series. N7283 .R69 2000 701’.18’095509024—dc21 00-062126 CIP Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Roxburgh, David J.: Prefacing the image : the writing of art history in sixteenth century Iran / by David J. Roxburgh. – Leiden; Boston; Köln : Brill, 2000 (Studies and sources in Islamic art and architectue; Vol 9) ISBN 90-04-11376-2 ISSN 0921-0326 ISBN 90 04 11376 2 © Copyright 2001 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. -

Mostly Modern Miniatures: Classical Persian Painting in the Early Twentieth Century

classical persian painting in the early twentieth century 359 MARIANNA SHREVE SIMPSON MOSTLY MODERN MINIATURES: CLASSICAL PERSIAN PAINTING IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY Throughout his various writings on Persian painting Bek Khur¸s¸nº or Tur¸basº Bek Khur¸s¸nº, seems to have published from the mid-1990s onwards, Oleg Grabar honed to a fi ne art the practice of creative reuse and has explored the place of the medium in traditional replication. Indeed, the quality of his production, Persian culture and expounded on its historiography, represented by paintings in several U.S. collections including the role played by private collections, muse- (including one on Professor Grabar’s very doorstep ums, and exhibitions in furthering public appreciation and another not far down the road), seems to war- and scholarly study of Persian miniatures.1 On the rant designating this seemingly little-known painter whole, his investigations have involved works created as a modern master of classical Persian painting. His in Iran and neighboring regions from the fourteenth oeuvre also prompts reconsideration of notions of through the seventeenth century, including some of authenticity and originality within this venerable art the most familiar and beloved examples within the form—issues that Oleg Grabar, even while largely canonical corpus of manuscript illustrations and min- eschewing the practice of connoisseurship himself, iature paintings, such as those in the celebrated 1396 recognizes as a “great and honorable tradition within Dºv¸n of Khwaju Kirmani, the 1488 Bust¸n of Sa{di, and the history of art.”5 the ca. 1525–27 Dºv¸n of Hafi z. -

Naqshbandi Sufi, Persian Poet

ABD AL-RAHMAN JAMI: “NAQSHBANDI SUFI, PERSIAN POET A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Farah Fatima Golparvaran Shadchehr, M.A. The Ohio State University 2008 Approved by Professor Stephen Dale, Advisor Professor Dick Davis Professor Joseph Zeidan ____________________ Advisor Graduate Program in History Copyright by Farah Shadchehr 2008 ABSTRACT The era of the Timurids, the dynasty that ruled Transoxiana, Iran, and Afghanistan from 1370 to 1506 had a profound cultural and artistic impact on the history of Central Asia, the Ottoman Empire, and Mughal India in the early modern era. While Timurid fine art such as miniature painting has been extensively studied, the literary production of the era has not been fully explored. Abd al-Rahman Jami (817/1414- 898/1492), the most renowned poet of the Timurids, is among those Timurid poets who have not been methodically studied in Iran and the West. Although, Jami was recognized by his contemporaries as a major authority in several disciplines, such as science, philosophy, astronomy, music, art, and most important of all poetry, he has yet not been entirely acknowledged in the post Timurid era. This dissertation highlights the significant contribution of Jami, the great poet and Sufi thinker of the fifteenth century, who is regarded as the last great classical poet of Persian literature. It discusses his influence on Persian literature, his central role in the Naqshbandi Order, and his input in clarifying Ibn Arabi's thought. Jami spent most of his life in Herat, the main center for artistic ability and aptitude in the fifteenth century; the city where Jami grew up, studied, flourished and produced a variety of prose and poetry. -

THE MAKING of the ARTIST in LATE TIMURID PAINTING Edinburgh Studies in Islamic Art Series Editor: Professor Robert Hillenbrand

EDINBURGH STUDIES IN ISLAMIC A RT EDINBURGH STUDIES IN ISLAMIC A RT S E RIES E DITOR:ROBE RT HILLE NBRAND Painting Timurid late in Artist the of Making The S E RIES E DITOR:ROBE RT HILLE NBRAND This series offers readers easy access to the most up-to-date research across the whole range of Islamic art, representing various parts of the Islamic world, media and approaches. Books in the series are academic monographs of intellectual distinction that mark a significant advance in the field. Isfahan and its Palaces Statecraft, Shi ’ ism and the Architecture of Conviviality in Early Modern Iran Sussan Babaie This beautifully illustrated history of Safavid Isfahan (1501–1722) explores the architectural and urban forms and networks of socio-cultural action that reflected a distinctly early modern and Perso-Shi ’ i practice of kingship. An immense building campaign, initiated in 1590/1, transformed Isfahan from a provincial, medieval and largely Sunni city into an urban-centered representation of the first Imami Shi ’ i empire in the history of Islam. The historical process of Shi ’ ification of Safavid Iran, and the deployment of the arts in situating the shifts in the politico-religious agenda of the imperial household, informs Sussan Babaie’s study of palatial architecture and urban environments of Isfahan and the earlier capitals of Tabriz and Qazvin. Babaie argues that, since the Safavid claim presumed the inheritance both of the charisma of the Shi ’ i Imams and of the aura of royal splendor integral to ancient Persian notions of kingship, a ceremonial regime was gradually devised in which access and proximity to the shah assumed the contours of an institutionalized form of feasting. -

Tadhkirat Al-Sh.U Lara

Mir Dawlatshah Samarqandi Tadhkirat al-sh.u lara Mir Dawlatshah Samarqandi was the son of Amir Ala'uddawla Bakhtishah Isfarayini, one of Shahrukh's courtiers, and nephew of the powerful Amir Firozshah. Unlike his fore- bears, who "passed their time as aristocrats in ostentatiousness and opulence," Mir Dawlatshah, who was of a dervish bent and had some poetic talent, "sought seclusion and contented himself with a life of spiritual poverty and rustication to acquire learning and perfection."! At the age of fifty he began his Tadhkirat al-shu'ara (Memorial of poets), anecdotes about and short biographies of 150 Persian poets, ancient and modern, which he completed in 892/1487. The judgment of Mir Ali-Sher Nawa'i, to whom the work was dedicated, was that "anyone who reads it will realize the merit and talent of the compiler." Although the book deals primarily with poets, since poets generally were inextricably bound to royal patrons, it contains valuable anecdotal information on many pre- Timurid, Timurid and Turcoman rulers. The synopses of rulers' careers and anecdotes illustrative of their characters included by Dawlatshah are translated and given here. * SULTANUWAYS JALAYIR2 out of a greedy poet's house is a difficult task," and gave him the candlestick. That [po288] It is said that one night Khwaja is how rulers rewarded poets in bygone Salman [Sawaji] was drinking in Sultan times.... Uways's assembly. As he departed, the sultan ordered a servant to light the way Dilshad Khatun was the noblest and for him with a candle in a golden candle- most beautiful lady of her time. -

Materials and Techniques of Islamic Manuscripts Penley Knipe1, Katherine Eremin1*, Marc Walton2, Agnese Babini2 and Georgina Rayner1

Knipe et al. Herit Sci (2018) 6:55 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-018-0217-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Materials and techniques of Islamic manuscripts Penley Knipe1, Katherine Eremin1*, Marc Walton2, Agnese Babini2 and Georgina Rayner1 Abstract Over 50 works on paper from Egypt, Iraq, Iran and Central Asia dated from the 13th to 19th centuries were examined and analyzed at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. Forty-six of these were detached folios, some of which had been removed from the same dispersed manuscript. Paintings and illuminations from fve intact manuscripts were also examined and analyzed, although not all of the individual works were included. The study was undertaken to better understand the materials and techniques used to create paintings and illuminations from the Islamic World, with particular attention paid to the diversity of greens, blues and yellows present. The research aimed to determine the full range of colorants, the extent of pigment mixing and the various preparatory drawing materials. The issue of binding materials was also addressed, albeit in a preliminary way. Keywords: Islamic manuscript, Islamic painting, XRF, Raman, FTIR, Imaging, Hyperspectral imaging Introduction project have been assigned to a particular town or region An ongoing interdisciplinary study at the Harvard Art and/or are well dated. Examination of folios from a single Museums is investigating the materials and techniques manuscript, including those now detached and dispersed used to embellish folios1 from Islamic manuscripts and as well as those still bound as a volume, enabled investi- albums created from the 13th through the 19th centuries. -

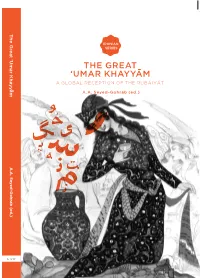

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

Stephen Album Rare Coins

STEPHEN ALBUM Specialist in Islamic and Indian Coins Post Office Box 7386, Santa Rosa, Calif. 95407, U.S.A. Telephone 707-539-2120 — Fax 707-539-3348 204 [email protected] http://www.stevealbum.com ANA, ANS, NI, ONS, CSNA, AVA Catalog price $2.00 28. Toghanshah, 1072-1082+, pale AV dinar (2.26 g), Herat, April 2005 date unclear, A-1678, citing Malikshah I, crude f $90 29. Sanjar, 1099-1118, pale AV dinar (2.6g) (Balkh), DM, A-1685A, as viceroy under Muhammad, with the Surat Gold Coins al-Kursi (Qur’an 2:255), f $125 30. AMIRS OF NISHAPUR: Toghanshah, 1172-1185, AV dinar (1.56 g) (Nishapur) DM, A-1708.2, 25% weak, citing Gold Coins of the Islamic Dynasties Takish, very crude vf $125 31. KHWARIZMSHAHS: ‘Ala al-Din Muhammad, 1200-1220, 1. ABBASID: al-Rashid, 786-809, AV dinar (3.56 g), without AV dinar (5.02 g), Bukhara DM, A-1712, 25% weakly mint, AH(19)3, A-218.13, clipped, li’l-khalifa below reverse, struck, very crude vf $125 vg-f $75 32. —, AV dinar (3.95g), Ghazna, DM, A-1712, attractive 2. al-Ma’mun, 810-833, AV dinar (3.22 g), [Madinat al-Salam] calligraphy, vf $115 AH207, A-222.15, clipped, double obverse margin type, 33. —, AV dinar (2.81 g), Tirmiz DM, A-1712, crimped, rare about f,R $120 mint now in Uzbekistan, crude vf $90 3. al-Mu’tamid, 870-892, AV dinar (4.29g), Madinat al-Salam, 34. GHORID: Mu’izz al-Din Muhammad, 1171-1206, AV dinar AH265, A-239.5, citing heir al-Muwaffaq, two plugged (2.90 g), Herat, DM, A-1763, 25% weakly struck, crude vf $125 holes, vf $120 35. -

The Art of Calligraphy Exercises (Siy@H Mashq) in Iran

practice makes perfect: the art of calligraphy exercises 107 MARYAM EKHTIAR PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT: THE ART OF CALLIGRAPHY EXERCISES (SIY@H MASHQ) IN IRAN Calligraphy is concealed in the teaching method of the letters, so that it be clear, clean, and attractive. When master; its essence is in its frequent repetition, and it your writing has made progress, seat yourself in a corner exists to serve Islam.1 and do not idle about; find some small manuscript of good style and hold it before your eyes. In the same These words by {Ali b. Abi Talib, traditionally regarded format, ruling, and kind of writing, prepare yourself to as the first master calligrapher of Islam, lie at the heart copy it. After that, write several letters; do not indulge in siy¸h mashq Siy¸h of , or calligraphic exercise pages. egotism. Try not to be careless with regard to your copy, mashq pages have yielded some of the most visually not even a little bit. One must give full attention to the stunning examples of later Persian calligraphy. Their copy, completing one line [of it] after another.3 bold forms and harmonious compositions are truly captivating. Yet this art form and its historical develop- Practice allowed the calligrapher to determine the size ment have received little attention from scholars and of the script to be used, to try out the pen, to judge art historians. Thus, in this study, I focus exclusively on whether or not the ink was of the correct consistency, and to map out the overall visual impact of the com- the development of siy¸h mashq in Iran: its visual and position. -

Composition and Role of the Nobility (1739-1761)

COMPOSITION AND ROLE OF THE NOBILITY (1739-1761) ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of ^l)iIo^op}|p IN HISTORY BY MD. SHAKIL AKHTAR Under the Supervision of DR. S. LIYAQAT H. MOINI (Reader) CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 ABSTRACT Foregoing study ' composition and role of the Nobility (1739- 1761)', explore the importance of Nobility in Political, administrative, Sicio-cultural and economic spheres. Nobility , 'Arkan-i-Daullat' (Pillars of Empire) generally indicates'the'class of people, who were holding hi^h position and were the officers of the king as well as of the state. This ruling elite constituting of various ethnic group based on class, political sphere. In Indian sub-continent they served the empire/state most loyally and obediently specially under the Great Mughals. They not only helped in the expansion of the Empire by leading campaign and crushing revolt for the consolidation of the empire, but also made remarkable and laudable contribution in the smooth running of the state machinery and played key role in the development of social life and composite culture. Mughal Emperor Akbar had organized the nobility based on mgnsabdari system and kept a watchful eye over the various groups, by introducing local forces. He had tried to keep a check and balance over the activities, which was carried by his able successors till the death of Aurangzeb. During the period of Later Mughals over ambitious, self centered and greedy nobles, kept their interest above state and the king and had started to monopolies power and privileges under their own authority either at the court or in the far off provinces.