Part 4: Conclusions and Recommendations & Appendices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

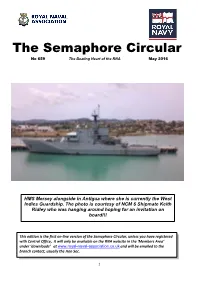

The Semaphore Circular No 659 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 659 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016 HMS Mersey alongside in Antigua where she is currently the West Indies Guardship. The photo is courtesy of NCM 6 Shipmate Keith Ridley who was hanging around hoping for an invitation on board!!! This edition is the first on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. April Open Day 2. New Insurance Credits 3. Blonde Joke 4. Service Deferred Pensions 5. Guess Where? 6. Donations 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. Finance Corner 9. RN VC Series – T/Lt Thomas Wilkinson 10. Golf Joke 11. Book Review 12. Operation Neptune – Book Review 13. Aussie Trucker and Emu Joke 14. Legion D’Honneur 15. Covenant Fund 16. Coleman/Ansvar Insurance 17. RNPLS and Yard M/Sweepers 18. Ton Class Association Film 19. What’s the difference Joke 20. Naval Interest Groups Escorted Tours 21. RNRMC Donation 22. B of J - Paterdale 23. Smallie Joke 24. Supporting Seafarers Day Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General -

Covid-19 - Royal Navy Staff Contact List Surname Forename L&D Hub Role Contact No

COVID-19 - ROYAL NAVY STAFF CONTACT LIST SURNAME FORENAME L&D HUB ROLE CONTACT NO. CONTACT EMAIL ARNOLD-BHATTI KHALIDA HMNB PORTSMOUTH eLA Work mob: 07513 483808 ASTON JIM 43 CDO RM CLYDE LT RN / OIC/ERO [email protected] Mil: 93255 6911, ATKINSON GARTH HMNB CLYDE LT CDR, RN [email protected] Civ: 01436 674321 Ext 6911 BAKER IAN RNAS Yeovilton Coord Contact Via TSM Contact via Pam Fisher BALLS SARA LDO APPS LT CDR, RN [email protected] BANKS TERRIE RNAS Yeovilton NRIO 07500 976770 Contact via Pam Fisher BEADNELL ROBERT HMNB PORTSMOUTH LT CDR, RN / OIC 07527 927699 BENNETT ZONA RNAS Yeovilton Coord Contact via Pam Fisher Contact via Pam Fisher BRADSHAW NICK 30 CDO RM, STONEHOUSE TUTOR 07376 335930 BRICE KAREN CTCRM IT Manager 07795 434832 Mil: 93781 2147 BRICKSTOCK STEPHEN RNAS CULDROSE OIC / ERO Civ: 01326 552147 [email protected] Mob: 07411 563346 BUTLER RACHEL HMNB DEVONPORT [email protected] CARPENTER NEIL 30 CDO RM, STONEHOUSE Co-ord / ELA 01752 217498 CHEAL ANDY LDO HQ CDR, RN 07976 455653 [email protected] CLARKE ELAINE RNAS CULDROSE Tutor 07962 118941 Contact via primary POC - OiC Steve Brickstock CLARKE SOPHIE RNAS CULDROSE EDO contact via OiC Contact via primary POC - OiC Steve Brickstock COLEMAN LAURA HMNB CLYDE [email protected] CRAWFORD COLJN NCHQ / HMS COLLINGWOOD RN ELC Scheme Manager [email protected] Mil: 9375 41509 DENWOOD MARTIN HMS RALEIGH OIC/ERO [email protected] Civ: 01752 811509 DRINKALL KATHRYN RNAS Yeovilton LT CDR, RN ASSIGNED TO COVID-19 [email protected] EASTERBROOK LEIGH 30 CDO RM, STONEHOUSE Co-ord/Reset/GCSEs 07770 618001 EWEN HAYLEY HMNB PORTSMOUTH Nelson Co-ord 02392 526420 1 09/04/20 SURNAME FORENAME L&D HUB ROLE CONTACT NO. -

The Referendum on Separation for Scotland

House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee The Referendum on Separation for Scotland Written evidence Only those submissions written specifically for the Committee and accepted by the Committee as evidence for the inquiry into the referendum on separation for Scotland are included. List of written evidence Page 1 Professor Bernard Ryan, Law School, University of Kent 1 2 Francis Tusa, Editor, Defence Analysis 8 3 Professor Jo Shaw, University of Edinburgh 14 4 Dr Phillips O’Brien, Scottish Centre for War Studies, University of Glasgow 21 5 Electoral Commission 24 6 Rt Hon Michael Moore MP, Secretary of State for Scotland 28 7 Ministry of Defence 29 8 Brian Buchan, Chief Executive, Scottish Engineering 46 9 Babcock 47 Written evidence from Professor Bernard Ryan, Law School, University of Kent Introduction If Scotland were to become independent, its relationship with the United Kingdom would have to be defined in the fields of nationality law and immigration law and policy. This note offers a summary of the relationship between the Irish state1 and the United Kingdom in those fields, and some thoughts on possible implications for Scottish independence. 1. Nationality Law 1.1 The Irish case A new nationality The nationality law of a new state must necessarily provide for two matters: an initial population of nationals on the date of independence, and the acquisition and loss of nationality on an ongoing basis. In the case of the Irish state, the initial population was defined by Article 3 of the Irish Free State Constitution of 1922. Article 3 conferred Irish Free State citizenship upon a person if they were domiciled in the “area of the jurisdiction of the Irish Free State” on the date the state was founded (6 December 1922), provided (a) they had been resident in that area for the previous seven years, or (b) they or one of their parents had been born in “Ireland”.2 A full framework of nationality law, covering all aspects of acquisition and loss of nationality, was not then adopted until the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1935. -

STATEMENT of REQUIREMENTS for the Supply of Upholstery and Soft

UPHOLSTERY AND SOFT FURNISHINGS STATEMENT OF REQUIREMENTS – MEDGS/0011 STATEMENT OF REQUIREMENTS for the supply of Upholstery and Soft Furnishings UPHOLSTERY AND SOFT FURNISHINGS STATEMENT OF REQUIREMENTS – MEDGS/0011 CONTENTS Section Title 1. Introduction 2. Quality, Defects and Non Conformance 3. Prices 4. Logistics 5. Development 6. Management 7. Key Performance Indicator 8. One Off Special Item or Service Requests 9. Electronic Catalogue Annexes A Distribution Addresses B Authorised Demanders B1 Delivery Addresses C Delivery Addresses D Deliveries Into Defence Storage And Distribution Agency Bicester and Donnington (DSDA) E One Off Special Items or Services F Key Performance Indicators G Procedure for P2P Demand Orders H Procedure for Non-P2P Demand Orders i UPHOLSTERY AND SOFT FURNISHINGS STATEMENT OF REQUIREMENTS – MEDGS/0011 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 This Statement of Requirements (StOR) sets out the Medical and General Supplies team's (M&GS) requirements for the supply of Textiles, Upholstery and soft furnishings requirements. 1.2 The Contractor shall supply the Articles and Services detailed in the SOR, as they are ordered by authorised Demanding Authorities listed at Annex B of this StOR and in the Master Database. The majority of demands under this Contract will be direct for the customers detailed in the Master Database. Demands for stock into the main delivery points will form the lesser part of the contract. As well as timely delivery of the Articles to the Authority, the Contractor must endeavour to achieve reductions in Article -

Summary History of the Trust a Personal Recollection

Summary History of the Trust A Personal Recollection Prepared by Peter Goodship Consultant Chief Executive June 2020 1. Introduction It is often said by historians seeking to justify their existence that "if you don't know where you have come from you cannot possibly know where you are going". The Chairman thought it might be helpful if I were to provide all current trustees with a potted history of the Trust from its inception in 1985 to assist your review of strategy. As part of my then role as Chief Executive’s Staff Officer, I was tasked by Portsmouth City Council to set up the Trust after having led the discussions with various agencies in the wake of the 1982 Defence Review. Several of you will recognise aspects of the history from your personal involvement and will no doubt have your own gloss on events and be in a position to expand on them. The views I express are my own, distilled from personal recollection and from research of our minute books, an extraordinarily valuable and precious archive. I have supplemented my own history with a copy of our last published account of our work covering the first twenty years from 1986 to 2006. This adds some colour to the narrative as well as capturing events I have not had the opportunity to cover in this summary. The document pre-dates the Trust’s acquisition of Priddy’s Hard and Explosion Museum from Gosport Borough Council and our revised proposals for the re-use of Boathouse 4. 2. The 1982 John Knott Review of Defence The Trust was born out of the Defence Review of 1982 which led to the closure of Chatham Dockyard, the privatisation of Devonport Dockyard and the slimming down of Portsmouth from a major ship building and repair facility to a Fleet Maintenance and Repair Organisation (FMRO). -

MFFW Diary 1914 HMS Drake.Pdf

Diary of Lieutenant Maurice Fiennes Fitzgerald Wilson, R.N. on board HMS Drake August - December 1914 INTRODUCTION nly the odd man out of many thousands, who begins a diary on any 1st of January, keeps it going. The one way to give a diary a real chance is to make O the keeping of it an offence. At the beginning of the Great War one of the first orders issued by the Admiralty was that which forbade the keeping of private diaries. This gave me (with many others - including Admiral Keyes, who should have known better) the necessary fillip; and I kept a record fairly continuously from the outbreak until the summer of 1919. Some branches of the Navy were fully extended by the war. The submarines, mine- sweepers, decoy-ships, barrage watchers, and many of the destroyer flotillas, in particular. They led a hard life and suffered heavy losses. Their service could fairly be compared with that of the soldiers. But most of the Navy lived in conditions hardly different from those of peace-time. Warmth, good housing, dry clothes, sanitation and cleanliness were with us all the time; and in the whole four years of war the average seaman heard less sound of angry gun-fire than troops on the Western Front might crowd into a few dirty minutes. So that, contrasted with army conditions, this is a peace diary. It has an interest for me, because it recalls the life we led, and reminds me that we lived - mentally - on hearsay, gossip, and rumour; by argument, forming theories, and piecing together stories from odd signals or other bits of news which we grabbed at as they wafted by. -

Naval Dockyards Society

20TH CENTURY NAVAL DOCKYARDS: DEVONPORT AND PORTSMOUTH CHARACTERISATION REPORT Naval Dockyards Society Devonport Dockyard Portsmouth Dockyard Title page picture acknowledgements Top left: Devonport HM Dockyard 1951 (TNA, WORK 69/19), courtesy The National Archives. Top right: J270/09/64. Photograph of Outmuster at Portsmouth Unicorn Gate (23 Oct 1964). Reproduced by permission of Historic England. Bottom left: Devonport NAAFI (TNA, CM 20/80 September 1979), courtesy The National Archives. Bottom right: Portsmouth Round Tower (1843–48, 1868, 3/262) from the north, with the adjoining rich red brick Offices (1979, 3/261). A. Coats 2013. Reproduced with the permission of the MoD. Commissioned by The Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England of 1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London, EC1N 2ST, ‘English Heritage’, known after 1 April 2015 as Historic England. Part of the NATIONAL HERITAGE PROTECTION COMMISSIONS PROGRAMME PROJECT NAME: 20th Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth (4A3.203) Project Number 6265 dated 7 December 2012 Fund Name: ARCH Contractor: 9865 Naval Dockyards Society, 44 Lindley Avenue, Southsea, PO4 9NU Jonathan Coad Project adviser Dr Ann Coats Editor, project manager and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Davies Editor and reviewer, project executive and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Evans Devonport researcher David Jenkins Project finance officer Professor Ray Riley Portsmouth researcher Sponsored by the National Museum of the Royal Navy Published by The Naval Dockyards Society 44 Lindley Avenue, Portsmouth, Hampshire, PO4 9NU, England navaldockyards.org First published 2015 Copyright © The Naval Dockyards Society 2015 The Contractor grants to English Heritage a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, perpetual, irrevocable and royalty-free licence to use, copy, reproduce, adapt, modify, enhance, create derivative works and/or commercially exploit the Materials for any purpose required by Historic England. -

The War Room Managed North Sea Trap 1907-1916

Michael H. Clemmesen 31‐12‐2012 The War Room Managed North Sea Trap 1907‐1916. The Substance, Roots and Fate of the Secret Fisher‐Wilson “War Plan”. Initial remarks In 1905, when the Royal Navy fully accepted the German High Seas Fleet as its chief opponent, it was already mastering and implementing reporting and control by wireless telegraphy. The Admiralty under its new First Sea Lord, Admiral John (‘Jacky’) Fisher, was determined to employ the new technology in support and control of operations, including those in the North Sea; now destined to become the main theatre of operations. It inspired him soon to believe that he could centralize operational control with himself in the Admiralty. The wireless telegraph communications and control system had been developed since 1899 by Captain, soon Rear‐Admiral Henry Jackson. Using the new means of communications and intelligence he would be able to orchestrate the destruction of the German High Seas Fleet. He already had the necessary basic intelligence from the planned cruiser supported destroyer patrols off the German bases, an operation based on the concept of the observational blockade developed by Captain George Alexander Ballard in the 1890s. Fisher also had the required The two officers who supplied the important basis for the plan. superiority in battleships to divide the force without the risk of one part being To the left: George Alexander Ballard, the Royal Navy’s main conceptual thinker in the two decades defeated by a larger fleet. before the First World War. He had developed the concept of the observational blockade since the 1890s. -

Collection Development Policy 2012-17

COLLECTION DEVELOPMENT POLICY 2012-17 CONTENTS Definition of terms used in the policy 3 Introduction 5 An historical introduction to the collections 8 The Collections Archaeology 11 Applied and Decorative Arts 13 Ceramics 13 Glass 14 Objets d‘Art 14 Jewellery 15 Furniture 16 Plate 16 Uniforms, Clothing and Textiles 17 Flags 18 Coins, Medals and Heraldry 20 Coins and Medals 20 Ship Badges, Heraldry and Seal Casts 21 Ethnography, Relics and Antiquities 23 Polar Equipment 23 Relics and Antiquities 23 Ethnographic Objects 24 Tools and Ship Equipment 26 Tools and Equipment 26 Figureheads and Ship Carvings 27 Cartography 30 Atlases, Charts, Maps and Plans 30 Globes and Globe Gores 31 Fine Arts 33 Oil Paintings 33 Prints and Drawings 34 Portrait Miniatures 35 Sculpture 36 Science and Technology 40 Astronomical Instruments 40 Navigational Instruments and Oceanography 42 Horology 43 Weapons and Ordnance 46 Edged Weapons 46 Firearms 47 Ordnance 49 Photographs and Film 52 Historic Photographs 52 Film Archive 54 Ship Plans and Technical Records 57 1 Boats and Ship Models 60 Boats 60 Models 60 Ethnographic Models 61 Caird Library and Archive 63 Archive Collections 63 Printed Ephemera 65 Rare Books 66 Legal, ethical and institutional contexts to acquisition and disposal 69 1.1 Legal and Ethical Framework 69 1.2 Principles of Collecting 69 1.3 Criteria for Collecting 70 1.4 Acquisition Policy 70 1.5 Acquisitions not covered by the policy 73 1.6 Acquisition documentation 73 1.7 Acquisition decision-making process 73 1.8 Disposal Policy 75 1.9 Methods of disposal 77 1.10 Disposal documentation 79 1.11 Disposal decision-making process 79 1.12 Collections Development Committee 79 1.13 Reporting Structure 80 1.14 References 81 Appendix 1. -

Fire! Heat! Sweat! Sand! and with Pride! an Ex-Employee of HM Dockyard, Portsmouth Looks Back

Fire! Heat! Sweat! Sand! and With Pride! An Ex-Employee of HM Dockyard, Portsmouth Looks Back. Chapter 1 - A NEW BEGINNING Is it a good thing to look back to the past? I suppose, really, it depends on whether one has had a very happy childhood and home life, or one of utter sadness and sorrow that the individual wishes to blot out the past totally for the rest of his or her life. That, one can sympathise certainly with the individual concerned. However in my case I was very lucky that I was in the former category. Yes, times were hard - my late lovely parents and my late lovely married sister, earning a living during the 1950s, found it hard to make ends meet; but we were very happy with what we had, and our home at No 7 Rochester Road Southsea, in the historic city of Portsmouth, right on the South Coast of the United Kingdom, and home of course to the Royal Navy.1 I am now retired but went out into the big wide world to earn a living, at the tender age of 15, in January 1960, my final year at school in 1959, my birthday falling in December of that year, as it does every year. I always wanted to work in the Portsmouth Naval Base, as it is now called, originally called H. M. Dockyard, but entry had to be gained by passing the Dockyard Exam. This was held at the old Apprentice Training Centre at Flathouse, Mile End in Portsmouth. This has long passed into the history books, along with the old Mile End Cemetery, Bailey & Whites large timber store - all now under the new Continental ferry port. -

Portsmouth Dockyard in the Twentieth Century1

PART THREE PORTSMOUTH DOCKYARD IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY1 3.1 INTRODUCTION The twentieth century topography of Portsmouth Dockyard can be related first to the geology and geography of Portsea Island and secondly to the technological development of warships and their need for appropriately sized and furnished docks and basins. In 2013, Portsmouth Naval Base covered 300 acres of land, with 62 acres of basin, 17 dry docks and locks, 900 buildings and 3 miles of waterfront (Bannister, 10 June 2013a). The Portsmouth Naval Base Property Trust (Heritage Area) footprint is 11.25 acres (4.56 hectares) which equates to 4.23% of the land area of the Naval Base or 3.5% of the total Naval Base footprint including the Basins (Duncan, 2013). From 8 or 9 acres in 1520–40 (Oppenheim, 1988, pp. 88-9), the dockyard was increased to 10 acres in 1658, to 95 acres in 1790, and gained 20 acres in 1843 for the steam basin and 180 acres by 1865 for the 1867 extension (Colson, 1881, p. 118). Surveyor Sir Baldwin Wake Walker warned the Admiralty in 1855 and again in 1858 that the harbour mouth needed dredging, as those [ships] of the largest Class could not in the present state of its Channel go out of Harbour, even in the event of a Blockade, in a condition to meet the Enemy, inasmuch as the insufficiency of Water renders it impossible for them to go out of Harbour with all their Guns, Coals, Ammunition and Stores on board. He noted further in 1858 that the harbour itself “is so blocked up by mud that there is barely sufficient space to moor the comparatively small Force at present there,” urging annual dredging to allow the larger current ships to moor there. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible.