Evidence for Disease-Related Amphibian Decline in Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disappearing Kettle Ponds Reveal a Drying Kenai Peninsula by Ed Berg

Refuge Notebook • Vol. 3, No. 38 • October 12, 2001 Disappearing kettle ponds reveal a drying Kenai Peninsula by Ed Berg A typical transect starts at the forest edge, passes through a grass (Calamagrostis) zone, into Sphagnum peat moss, and then into wet sedges, sometimes with pools of standing water, and then back through these same zones on the other side of the kettle. Three of the four kettles we surveyed this summer were quite wet in the middle (especially after the July rains), and we had to wear hip boots. These plots can be resurveyed in future decades and, if I am correct, they will show a succession of drier and drier plants as the water table drops lower and lower, due to warmer summers and increased evap- Photo of a kettle pond by the National Park Service. otranspiration. If I am wrong, and the climate trend turns around toward cooler and wetter, these plots will When the glaciers left the Soldotna-Sterling area be under water again, as they were on the old aerial some 14,000 years ago, the glacier fronts didn’t re- photos. cede smoothly like their modern descendants, such as By far the most striking feature that we have Portage or Skilak glaciers. observed in the kettles is a band of young spruce Rather, the flat-lying ice sheets broke up into nu- seedlings popping up in the grass zones. These merous blocks, which became partially buried in hilly seedlings can form a halo around the perimeter of a moraines and flat outwash plains. In time these gi- kettle. -

Hogback Trail Greenfield State Park Greenfield, New Hampshire

Hogback Trail Greenfield State Park Greenfield, New Hampshire Self-Guided Hike 1. The Hogback Trail is 1.2 miles long and relatively flat. It will take you approximately 45 minutes to go around the pond. As you walk, keep an eye out for the abundant wildlife and unique plants that are in this secluded area of the park. Throughout the trail, there are numbered stations that correspond to this guide and benches to rest upon. Practice “Leave No Trace” on your hike; Take only photographs, leave only footprints. 2. Hogback Pond is a glacial kettle pond formed when massive chunks of Stop #5: ridge is an example of glacial esker ice were buried in the sand, then slowly melted leaving a huge depression in the landscape that eventually filled with water. Kettle ponds generally have no streams running into them or out of them, resulting in a still body of water. Water in the pond is replenished by rain and is acidic, prohibiting many common wetland species from flourishing. 3. The blueberry bushes around Hogback Pond and throughout Greenfield State Park are two species; low-bush and high-bush. Many animals such as Black Bear and several species of birds seek out these berries as an important summer food source. Between Stops #2 & 3: example of unique vegetation found on kettle ponds 4. The Eastern Hemlocks that you see around you are one of the several varieties of evergreen that grow around Hogback Pond. This slow- growing, long-lived tree grows well in the shade. They have numerous short needles spreading directly from the branches in one flat layer. -

Des Moines Lobe Retreated North- What It Means to Be Minnesotan

Route Map Geology of the Carleton College Esri, HERE, DeLorme, MapmyIndia, © OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS ¯ user community 1 Cannon River Cowling Arboretum 2 Glacial Landscapes 3 Glacial Erratics 4 Local Bedrock A Guided Tour 5 Kettle Hole Marsh College BoundaryH - Back IA Parking Glacial Erratic Cannon River Tour Route Other Trails 0250 500 1 000 Feet, 5 HWY 3 4 LOWER ARBORETUM 3 2 H IA 1 Arb Office HWY 19 UPPER Tunnel IA ARBORETUM under Hwy 19 Lower Lyman Recreation IA Center HALL AVE HALL West IA Gym Library Published 5/2016 Product of the Carleton College Cowling Arboretum. For more information visit our website: apps.carleton.edu/campus/arb or contact us at (507)-222-4543 Introduction Hello and welcome to Carleton College’s Cowling Arboretum. This 1 800 acre natural area, owned and managed by Carleton, has long been one of the most beloved parts of Carleton for students, faculty and community members alike. Although the Arb is best known for its prairie ecosystem, an amazing history full of thundering riv- ers, massive glaciers, and the journeys of massive boulders lies just below the surface. This geologic history of the Arb is a fascinating story and one that you can experience for yourself by following this 2 self-guided tour. I hope it’s a beautiful day for a walk hope and that you enjoy learning about the geology of the Arb as much as I did. The route for this tour is about three miles long and will take you 1-2 hours to complete, depending on your walking speed. -

Chapter One the Vision of A

Oak Ridges Trail Association 1992 - 2017 The Vision of a Moraine-wide Hiking Trail Chapter One CHAPTER ONE The Oak Ridges Moraine is defined by a sub-surface geologic formation. It is evident as a 170 km long ridge, a watershed divide between Lake Ontario to the south and Lake Simcoe, Lake Scugog and Rice Lake to the north. Prior to most THE VISION OF A MORAINE-WIDE HIKING TRAIL being harvested, Red Oak trees flourished along the ridge – hence its name. Appended to this chapter is an account of the Moraine’s formation, nature and Where and What is the Oak Ridges Moraine? history written by two Founding Members of the Oak Ridges Trail Association. 1 Unlike the Niagara Escarpment, the Oak Ridges Moraine is not immediately observed when travelling through the region. During the 1990s when the Oak The Seeds of the Vision Ridges Moraine became a news item most people in the Greater Toronto Area had no idea where it was. Even local residents and visitors who enjoyed its From the 1960s as the population and industrialization of Ontario, particularly particularly beautiful landscape characterized by steep rolling hills and substantial around the Golden Horseshoe from Oshawa to Hamilton grew rapidly, there was forests had little knowledge of its boundaries or its significance as a watershed. an increasing awareness of the stress this placed on the environment, particularly on the congested Toronto Waterfront and the western shore of Lake Ontario. The vision of a public footpath that would span the entire Niagara Escarpment - the Bruce Trail - came about in 1959 out of a meeting between Ray Lowes and Robert Bateman of the Federation of Ontario Naturalists. -

Pine Hill Esker Trail

mature forest, crosses a meadow and goes back 1.04 miles: Trail turn-around, at the location of into forested terrain. Unique for this trail are its wetland and a permanent stream. eskers and kettle ponds and the views of a 1.19 miles: Optional (but recommended) side wetland pond where Rocky Brook flows into the loop on the left side, shortly after remnants of the Stillwater River. The trail is located on DCR circular track. watershed protection land, so dogs are not 1.23 miles: Trail loops gently to the right. Deep allowed. down to the left is a small pond (a kettle pond). Length and Difficulty 1.32 miles: Side trail rejoins the return trail. 1.55 miles: Trail junction of Sections A, B and C. For clarity, the trail is divided into three sections: The trail description continues with Sect. C A, B and C, with one-way lengths of 0.65 mi., 0.45 outbound. mi. and 0.45 mi., respectively. The full hike, as 1.58 miles: Wet area most of the times of the described below, includes all three sections. The year. side loop on Sect. B is included on the return. The 1.78 miles: View to wetland pond where the A+B+C trail length is 3.1 mi., while the two shorter Stillwater River meets Rocky Brook. The distant versions, A+B or A+C, are both 2.2 mi. in length. structure is part of the Sterling water system. The elevation varies between 428 ft and 540 ft, 2.00 miles: Trail turn around point at the edge of with several short steep hills. -

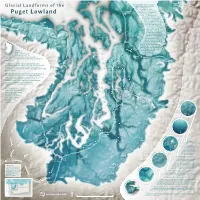

Glacial Landforms of the Puget Lowland

Oak Harbor i t S k a g Sauk Suiattle Suiattle River B a y During the advance and retreat of Indian Reservation Glacial Landforms of the the Puget lobe, drainages around the ice sheet were blocked, forming multiple proglacial Camano Island Stillaguamish lakes. The darker colors on this Indian map indicate lower elevations, Reservation Puget Lowland and show many of these t S Arlington Spi ss valleys. The Stillaguamish, e a en P g n o Snohomish, Snoqualmie, and Striped Peak u r D r Hook a Puyallup River valleys all once t z US Interstate 5 Edi Sauk River Lower Elwha t S contained proglacial lakes. Klallam o u s There are many remnants of Indian g Port a Reservation US Highway 101 Jamestown Townsend a n these lakes left today, such as S’Klallam A Quimper Peninsula Port Angeles Indian Lake Washington and Lake d Reservation Sequim P Sammamish, east of Seattle. o m H P Miller Peninsula r t o a S T l As the Puget lobe retreated, i m Tulalip e o s w McDonald Mountain q r e Indian lake outflows, glacial D n s u i s s s Reservation i c e a m o a H S. F. Stillaguamish River v n meltwater, and glacial outburst e d a g Marysville B r B l r e a y a b flooding all contributed to y o y t Elwha River B r dozens of channels that flowed y a y southwest to the Chehalis River Round Mountain Lookout Hill Lake Stevens I Whidbey Island at the southwest corner of this n d map. -

Fjord Oceanographic Processes in Glacier Bay, Alaska

Fjord Oceanographic Processes in Glacier Bay, Alaska Philip N. Hooge and Elizabeth Ross Hooge Prepared for the National Park Service, Glacier Bay National Park USGS-Alaska Science Center Glacier Bay Field Station P.O. Box 140 Gustavus, AK 99826-0140 March 2002 Fjord Oceanographic Processes in Glacier Bay, Alaska Philip N. Hooge Elizabeth Ross Hooge Prepared for the National Park Service, Glacier Bay National Park USGS – Alaska Science Center Glacier Bay Field Station P.O. Box 140 Gustavus, AK 99826-0140 March 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary..................................................................3 II. Fjord Oceanography of Glacier Bay, Alaska .....................7 Introduction........................................................................................... 7 Study Site and Methods.................................................................... 10 Results ............................................................................................... 14 Discussion.......................................................................................... 24 Literature Cited .................................................................................. 38 Figures ............................................................................................... 44 III. Oceanographic Data Resources At Glacier Bay.............83 IV. Resource Needs For An Oceanographic Monitoring Program At Glacier Bay ...................................................88 V. Proposed Future Oceanographic Research .....................91 -

Massachusetts Estuaries Project

Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Approach to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for the Swan Pond River Embayment System Town of Dennis, Massachusetts University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Massachusetts Department of School of Marine Science and Technology Environmental Protection FINAL REPORT – October 2012 Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for the Swan Pond River Embayment System Town of Dennis, Massachusetts FINAL REPORT – October 2012 Brian Howes Ed Eichner Roland Samimy David Schlezinger Trey RuthvenJohn Ramsey Phil "Jay" Detjens Contributors: US Geological Survey Don Walters and John Masterson Applied Coastal Research and Engineering, Inc. Elizabeth Hunt Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Charles Costello and Brian Dudley (DEP P.M.) SMAST Coastal Systems Program Jennifer Benson, Michael Bartlett, Sara Sampieri Cape Cod Commission Tom Cambareri Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for the Swan Pond River Embayment System, Dennis, Massachusetts Executive Summary 1. Background This report presents the results generated from the implementation of the Massachusetts Estuaries Project’s Linked Watershed-Embayment Approach to the Swan Pond River embayment system, a coastal embayment primarily within the Town of Dennis, Massachusetts (very small portions of the overall watershed extend into the Towns of Harwich and Brewster). Analyses of the Swan Pond River embayment system was performed to assist the Town of Dennis with up-coming nitrogen management decisions associated with the current and future wastewater planning efforts of the Town, as well as wetland restoration, anadromous fish runs, shell fishery, open-space, and harbor maintenance programs. -

Glacial Terminology

NRE 430 / EEB 489 D.R. Zak 2003 Lab 1 Glacial Terminology The last glacial advance in Michigan is known as the Wisconsin advance. The late Wisconsin period occurred between 25,000 and 10,000 years ago. Virtually all of Michigan's present surface landforms were shaped during this time. A. Glacial Materials Glacial Drift: material transported and deposited by glacial action. Note that most glacial features are recessional, i.e., they are formed by retreating ice. Materials deposited during glacial advance are usually overridden and destroyed or buried before the glacier has reached its maximum. Till: unstratified drift (e.g., material not organized into distinct layers), ice-transported, highly variable, may consist of any range of particles from clay to boulders. Ice-deposited material is indicated by random assemblage of particle sizes, such as clay, sand and cobbles mixed together. Ice-worked material is indicated by sharp-edged or irregular shaped pebbles and cobbles, formed by the coarse grinding action of the ice. Outwash: stratified drift (e.g., material organized into distinct horizontal layers or bands), water-transported, consists mainly of sand (fine to coarse) and gravel rounded in shape. Meltwater streams flowing away from glacier as it recedes carries particles that are sorted by size on deposition dependent upon the water flow velocity – larger particles are deposited in faster moving water. Water-deposited material is indicated by stratified layers of different sized sand particles and smooth rounded pebbles, consistent in size within each band. Water-worked material is indicated by smooth, rounded particles, formed by the fine grinding action of particles moved by water. -

Massachusetts Estuaries Project

Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Sesachacha Pond, Town of Nantucket, Massachusetts Quidnet Sesachahcha Pond Hoicks Hollow University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Massachusetts Department of School of Marine Science and Technology Environmental Protection FINAL REPORT – NOVEMBER 2006 Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Sesachacha Pond, Town of Nantucket Nantucket Island, Massachusetts FINAL REPORT – NOVEMBER 2006 Brian Howes Roland Samimy David Schlezinger Sean Kelley John Ramsey Mark Osler Ed Eichner Contributors: US Geological Survey Don Walters and John Masterson Applied Coastal Research and Engineering, Inc. Elizabeth Hunt Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Charles Costello and Brian Dudley (DEP manager) SMAST Coastal Systems Program George Hampson and Sara Sampieri Cape Cod Commission Xiaotong Wu © [2006] University of Massachusetts All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Massachusetts Estuaries Project Technical Team would like to acknowledge the contributions of the many individuals who have worked tirelessly for the restoration and protection of the critical coastal resources of the Nantucket Harbor System. Without these stewards and their efforts, this project would not have been possible. First and foremost is the significant time and effort in data collection and discussion spent by members of the Town of Nantucket Water Quality Monitoring Program, particularly Dave Fronzuto and its Coordinator, Keith Conant and former Coordinator, Tracey Curley. These individuals gave of their time to collect nutrient samples from this system over many years and without this information, the present analysis would not have been possible. A special thank you is extended to Richard Ray of the Town of Nantucket Health Department for all the assistance provided over the years thus making this report as specific as possible to the Island. -

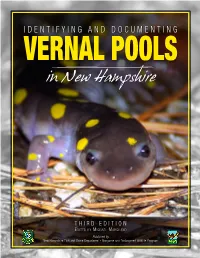

Identifying and Documenting Vernal Pools in New Hampshire 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IDENTIFYING AND DOCUMENTING VERNAL POOLS _ in New Hampshire THIRD EDITION EDITED BY MICHAEL MARCHAND Published by New Hampshire Fish and Game Department l Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program IDENTIFYING AND DOCUMENTING VERNAL POOLS _ in New Hampshire THIRD EDITION EDITED BY MICHAEL MARCHAND Published by New Hampshire Fish and Game Department Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program Identifying and Documenting Vernal Pools in New Hampshire 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is the third edition of the The Identification and Documentation of Vernal Pools in New Hampshire, and many people have assisted in the development and improvement of this publication over the years. All editions have been published by the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department's Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program, in conjunction with the Public Affairs Division. Funds for the development of the third edition came from the Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program, N.H. Fish and Game Department, including Conservation License Plate (Moose Plate) funds and a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The third edition was edited by Michael Marchand, wildlife biologist for the N.H. Fish and Game Department's Nongame Program. The following individuals provided text, thoughtful comments, and edits to the manual: Loren Valliere, N.H. Fish and Game Department, Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Program; Sandy Crystal, Sandi Mattfeldt and Mary Ann Tilton, N.H. Department of Environ- mental Services, Wetlands Bureau; and Brett Thelen, Harris Center for Conservation Education. Pamela Riel, N.H. Fish and Game Publications Manager (Public Affairs Divi- sion), did the layout. Graphic Designer Victor Young, also of Fish and Game's Public Affairs Division, formatted images for publication, provided artwork and designed the cover. -

Massachusetts Estuaries Project

MASSACHUSETTS ESTUARIES PROJECT Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for the Oyster Pond System, Falmouth, Massachusetts University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Massachusetts Department of School of Marine Science and Technology Environmental Protection FINAL REPORT –JANUARY 2006 Massachusetts Estuaries Project Linked Watershed-Embayment Model to Determine Critical Nitrogen Loading Thresholds for Oyster Pond System, Falmouth, Massachusetts FINAL REPORT – January 2006 Brian Howes Roland Samimy David Schlezinger Sean Kelley John Ramsey Ed Eichner Contributors: US Geological Survey Don Walters and John Masterson Applied Coastal Research and Engineering, Inc. Elizabeth Hunt Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Brian Dudley (DEP project manager) SMAST Coastal Systems Program George Hampson, Sara Sampieri, Jen Antosca, and Michael Bartlett © [2006] University of Massachusetts All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Massachusetts Estuaries Project Technical Team would like to acknowledge the contributions of the many individuals who have worked tirelessly for the restoration and protection of the critical coastal resources of the Oyster Pond System. Without these stewards and their efforts, this project would not have been possible. First and foremost is the significant time and effort in data collection and discussion spent by members of the Falmouth PondWatch Water Quality Monitoring Program, particularly B. Norris, J. Dowling, B. Livingstone, J. Rankin M. Zinn, D. Zinn. These individuals gave of their time to collect nutrient samples from this system over many years and without this information the present analysis would not have been possible. In addition, over the years the Oyster Pond Environmental Trust (OPET) has worked tirelessly with SMAST Coastal Systems Staff, engineers from Applied Coastal Research and Engineering and the Town of Falmouth Engineering Department in order to develop a management strategy for this system.