Belgrade Esker and Kettle Complex Beginning with Focus Areas of Statewide Ecological Significance Habitat Belgrade Esker and Kettle Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disappearing Kettle Ponds Reveal a Drying Kenai Peninsula by Ed Berg

Refuge Notebook • Vol. 3, No. 38 • October 12, 2001 Disappearing kettle ponds reveal a drying Kenai Peninsula by Ed Berg A typical transect starts at the forest edge, passes through a grass (Calamagrostis) zone, into Sphagnum peat moss, and then into wet sedges, sometimes with pools of standing water, and then back through these same zones on the other side of the kettle. Three of the four kettles we surveyed this summer were quite wet in the middle (especially after the July rains), and we had to wear hip boots. These plots can be resurveyed in future decades and, if I am correct, they will show a succession of drier and drier plants as the water table drops lower and lower, due to warmer summers and increased evap- Photo of a kettle pond by the National Park Service. otranspiration. If I am wrong, and the climate trend turns around toward cooler and wetter, these plots will When the glaciers left the Soldotna-Sterling area be under water again, as they were on the old aerial some 14,000 years ago, the glacier fronts didn’t re- photos. cede smoothly like their modern descendants, such as By far the most striking feature that we have Portage or Skilak glaciers. observed in the kettles is a band of young spruce Rather, the flat-lying ice sheets broke up into nu- seedlings popping up in the grass zones. These merous blocks, which became partially buried in hilly seedlings can form a halo around the perimeter of a moraines and flat outwash plains. In time these gi- kettle. -

WELLESLEY TRAILS Self-Guided Walk

WELLESLEY TRAILS Self-Guided Walk The Wellesley Trails Committee’s guided walks scheduled for spring 2021 are canceled due to Covid-19 restrictions. But… we encourage you to take a self-guided walk in the woods without us! (Masked and socially distanced from others outside your group, of course) Geologic Features Look for geological features noted in many of our Self-Guided Trail Walks. Featured here is a large rock polished by the glacier at Devil’s Slide, an esker in the Town Forest (pictured), and a kettle hole and glacial erratic at Kelly Memorial Park. Devil’s Slide 0.15 miles, 15 minutes Location and Parking Park along the road at the Devil’s Slide trailhead across the road from 9 Greenwood Road. Directions From the Hills Post Office on Washington Street, turn onto Cliff Road and follow for 0.4 mile. Turn left onto Cushing Road and follow as it winds around for 0.15 mile. Turn left onto Greenwood Road, and immediately on your left is the trailhead in patch of woods. Walk Description Follow the path for about 100 yards to a large rock called the Devil’s Slide. Take the path to the left and climb around the back of the rock to get to the top of the slide. Children like to try out the slide, which is well worn with use, but only if it is dry and not wet or icy! Devil’s Slide is one of the oldest rocks in Wellesley, more than 600,000,000 years old and is a diorite intrusion into granite rock. -

An Esker Group South of Dayton, Ohio 231 JACKSON—Notes on the Aphididae 243 New Books 250 Natural History Survey 250

The Ohio Naturalist, PUBLISHED BY The Biological Club of the Ohio State University. Volume VIII. JANUARY. 1908. No. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS. SCHEPFEL—An Esker Group South of Dayton, Ohio 231 JACKSON—Notes on the Aphididae 243 New Books 250 Natural History Survey 250 AN ESKER GROUP SOUTH OF DAYTON, OHIO.1 EARL R. SCHEFFEL Contents. Introduction. General Discussion of Eskers. Preliminary Description of Region. Bearing on Archaeology. Topographic Relations. Theories of Origin. Detailed Description of Eskers. Kame Area to the West of Eskers. Studies. Proximity of Eskers. Altitude of These Deposits. Height of Eskers. Composition of Eskers. Reticulation. Rock Weathering. Knolls. Crest-Lines. Economic Importance. Area to the East. Conclusion and Summary. Introduction. This paper has for its object the discussion of an esker group2 south of Dayton, Ohio;3 which group constitutes a part of the first or outer moraine of the Miami Lobe of the Late Wisconsin ice where it forms the east bluff of the Great Miami River south of Dayton.4 1. Given before the Ohio Academy of Science, Nov. 30, 1907, at Oxford, O., repre- senting work performed under the direction of Professor Frank Carney as partial requirement for the Master's Degree. 2. F: G. Clapp, Jour, of Geol., Vol. XII, (1904), pp. 203-210. 3. The writer's attention was first called to the group the past year under the name "Morainic Ridges," by Professor W. B. Werthner, of Steele High School, located in the city mentioned. Professor Werthner stated that Professor August P. Foerste of the same school and himself had spent some time together in the study of this region, but that the field was still clear for inves- tigation and publication. -

Hogback Trail Greenfield State Park Greenfield, New Hampshire

Hogback Trail Greenfield State Park Greenfield, New Hampshire Self-Guided Hike 1. The Hogback Trail is 1.2 miles long and relatively flat. It will take you approximately 45 minutes to go around the pond. As you walk, keep an eye out for the abundant wildlife and unique plants that are in this secluded area of the park. Throughout the trail, there are numbered stations that correspond to this guide and benches to rest upon. Practice “Leave No Trace” on your hike; Take only photographs, leave only footprints. 2. Hogback Pond is a glacial kettle pond formed when massive chunks of Stop #5: ridge is an example of glacial esker ice were buried in the sand, then slowly melted leaving a huge depression in the landscape that eventually filled with water. Kettle ponds generally have no streams running into them or out of them, resulting in a still body of water. Water in the pond is replenished by rain and is acidic, prohibiting many common wetland species from flourishing. 3. The blueberry bushes around Hogback Pond and throughout Greenfield State Park are two species; low-bush and high-bush. Many animals such as Black Bear and several species of birds seek out these berries as an important summer food source. Between Stops #2 & 3: example of unique vegetation found on kettle ponds 4. The Eastern Hemlocks that you see around you are one of the several varieties of evergreen that grow around Hogback Pond. This slow- growing, long-lived tree grows well in the shade. They have numerous short needles spreading directly from the branches in one flat layer. -

Eskers Formed at the Beds of Modern Surge-Type Tidewater Glaciers in Spitsbergen

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Apollo Eskers formed at the beds of modern surge-type tidewater glaciers in Spitsbergen J. A. DOWDESWELL1* & D. OTTESEN2 1Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 1ER, UK 2Geological Survey of Norway, Postboks 6315 Sluppen, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Eskers are sinuous ridges composed of glacifluvial sand and gravel. They are deposited in channels with ice walls in subglacial, englacial and supraglacial positions. Eskers have been observed widely in deglaciated terrain and are varied in their planform. Many are single and continuous ridges, whereas others are complex anastomosing systems, and some are successive subaqueous fans deposited at retreating tidewater glacier margins (Benn & Evans 2010). Eskers are usually orientated approximately in the direction of past glacier flow. Many are formed subglacially by the sedimentary infilling of channels formed in ice at the glacier base (known as ‘R’ channels; Röthlisberger 1972). When basal water flows under pressure in full conduits, the hydraulic gradient and direction of water flow are controlled primarily by ice- surface slope, with bed topography of secondary importance (Shreve 1985). In such cases, eskers typically record the former flow of channelised and pressurised water both up- and down-slope. Description Sinuous sedimentary ridges, orientated generally parallel to fjord axes, have been observed on swath-bathymetric images from several Spitsbergen fjords (Ottesen et al. 2008). In innermost van Mijenfjorden, known as Rindersbukta, and van Keulenfjorden in central Spitsbergen, the fjord floors have been exposed by glacier retreat over the past century or so (Ottesen et al. -

Trip F the PINNACLE HILLS and the MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A

F-1 Trip F THE PINNACLE HILLS AND THE MENDON KAME AREA: CONTRASTING MORAINAL DEPOSITS by Robert A. Sanders Department of Geosciences Monroe Community College INTRODUCTION The Pinnacle Hills, fortunately, were voluminously described with many excellent photographs by Fairchild, (1923). In 1973 the Range still stands as a conspicuous east-west ridge extending from the town of Brighton, at about Hillside Avenue, four miles to the Genesee River at the University of Rochester campus, referred to as Oak Hill. But, for over thirty years the Range was butchered for sand and gravel, which was both a crime and blessing from the geological point of view (plates I-VI). First, it destroyed the original land form shapes which were subsequently covered with man-made structures drawing the shade on its original beauty. Secondly, it allowed study of its structure by a man with a brilliantly analytical mind, Herman L. Fair child. It is an excellent example of morainal deposition at an ice front in a state of dynamic equilibrium, except for minor fluctuations. The Mendon Kame area on the other hand, represents the result of a block of stagnant ice, probably detached and draped over drumlins and drumloidal hills, melting away with tunnels, crevasses, and per foration deposits spilling or squirting their included debris over a more or less square area leaving topographically high kames and esker F-2 segments with many kettles and a large central area of impounded drainage. There appears to be several wave-cut levels at around the + 700 1 Lake Dana level, (Fairchild, 1923). The author in no way pretends to be a Pleistocene expert, but an attempt is made to give a few possible interpretations of the many diverse forms found in the Mendon Kames area. -

Des Moines Lobe Retreated North- What It Means to Be Minnesotan

Route Map Geology of the Carleton College Esri, HERE, DeLorme, MapmyIndia, © OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS ¯ user community 1 Cannon River Cowling Arboretum 2 Glacial Landscapes 3 Glacial Erratics 4 Local Bedrock A Guided Tour 5 Kettle Hole Marsh College BoundaryH - Back IA Parking Glacial Erratic Cannon River Tour Route Other Trails 0250 500 1 000 Feet, 5 HWY 3 4 LOWER ARBORETUM 3 2 H IA 1 Arb Office HWY 19 UPPER Tunnel IA ARBORETUM under Hwy 19 Lower Lyman Recreation IA Center HALL AVE HALL West IA Gym Library Published 5/2016 Product of the Carleton College Cowling Arboretum. For more information visit our website: apps.carleton.edu/campus/arb or contact us at (507)-222-4543 Introduction Hello and welcome to Carleton College’s Cowling Arboretum. This 1 800 acre natural area, owned and managed by Carleton, has long been one of the most beloved parts of Carleton for students, faculty and community members alike. Although the Arb is best known for its prairie ecosystem, an amazing history full of thundering riv- ers, massive glaciers, and the journeys of massive boulders lies just below the surface. This geologic history of the Arb is a fascinating story and one that you can experience for yourself by following this 2 self-guided tour. I hope it’s a beautiful day for a walk hope and that you enjoy learning about the geology of the Arb as much as I did. The route for this tour is about three miles long and will take you 1-2 hours to complete, depending on your walking speed. -

Chapter One the Vision of A

Oak Ridges Trail Association 1992 - 2017 The Vision of a Moraine-wide Hiking Trail Chapter One CHAPTER ONE The Oak Ridges Moraine is defined by a sub-surface geologic formation. It is evident as a 170 km long ridge, a watershed divide between Lake Ontario to the south and Lake Simcoe, Lake Scugog and Rice Lake to the north. Prior to most THE VISION OF A MORAINE-WIDE HIKING TRAIL being harvested, Red Oak trees flourished along the ridge – hence its name. Appended to this chapter is an account of the Moraine’s formation, nature and Where and What is the Oak Ridges Moraine? history written by two Founding Members of the Oak Ridges Trail Association. 1 Unlike the Niagara Escarpment, the Oak Ridges Moraine is not immediately observed when travelling through the region. During the 1990s when the Oak The Seeds of the Vision Ridges Moraine became a news item most people in the Greater Toronto Area had no idea where it was. Even local residents and visitors who enjoyed its From the 1960s as the population and industrialization of Ontario, particularly particularly beautiful landscape characterized by steep rolling hills and substantial around the Golden Horseshoe from Oshawa to Hamilton grew rapidly, there was forests had little knowledge of its boundaries or its significance as a watershed. an increasing awareness of the stress this placed on the environment, particularly on the congested Toronto Waterfront and the western shore of Lake Ontario. The vision of a public footpath that would span the entire Niagara Escarpment - the Bruce Trail - came about in 1959 out of a meeting between Ray Lowes and Robert Bateman of the Federation of Ontario Naturalists. -

Pine Hill Esker Trail

mature forest, crosses a meadow and goes back 1.04 miles: Trail turn-around, at the location of into forested terrain. Unique for this trail are its wetland and a permanent stream. eskers and kettle ponds and the views of a 1.19 miles: Optional (but recommended) side wetland pond where Rocky Brook flows into the loop on the left side, shortly after remnants of the Stillwater River. The trail is located on DCR circular track. watershed protection land, so dogs are not 1.23 miles: Trail loops gently to the right. Deep allowed. down to the left is a small pond (a kettle pond). Length and Difficulty 1.32 miles: Side trail rejoins the return trail. 1.55 miles: Trail junction of Sections A, B and C. For clarity, the trail is divided into three sections: The trail description continues with Sect. C A, B and C, with one-way lengths of 0.65 mi., 0.45 outbound. mi. and 0.45 mi., respectively. The full hike, as 1.58 miles: Wet area most of the times of the described below, includes all three sections. The year. side loop on Sect. B is included on the return. The 1.78 miles: View to wetland pond where the A+B+C trail length is 3.1 mi., while the two shorter Stillwater River meets Rocky Brook. The distant versions, A+B or A+C, are both 2.2 mi. in length. structure is part of the Sterling water system. The elevation varies between 428 ft and 540 ft, 2.00 miles: Trail turn around point at the edge of with several short steep hills. -

Esker Habitat Characteristics and Traditional Land Use in the Slave Geological Province

Re: Esker Habitat Characteristics and Traditional Land Use in the Slave Geological Province STUDY DIRECTOR RELEASE FORM The above publication is the result of a project conducted under the West Kitikmeot / Slave Study. I have reviewed the report and advise that it has fulfilled the requirements of the approved proposal and can be subjected to independent expert review and be considered for release to the public. Study Director Date INDEPENDENT EXPERT REVIEW FORM I have reviewed this publication for scientific content and scientific practices and find the report is acceptable given the specific purposes of this project and subject to the field conditions encountered. Reviewer Date INDEPENDENT EXPERT REVIEW FORM I have reviewed this publication for scientific content and scientific practices and find the report is acceptable given the specific purposes of this project and subject to the field conditions encountered. Reviewer Date BOARD RELEASE FORM The Study Board is satisfied that this final report has been reviewed for scientific content and approves it for release to the public. Chair West Kitikmeot/Slave Society Date Box 2572, Yellowknife, NT, X1A 2P9 Ph (867) 669-6235 Fax (867) 920-4346 e-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.wkss.nt.ca ESKER HABITAT CHARACTERISTICS and TRADITIONAL USE STUDY in the SLAVE GEOLOGICAL PROVINCE FINAL REPORT to the WEST KITIKMEOT / SLAVE STUDY Submitted by: Stephen Traynor Senior Land Specialist – Land Administration Indian and Northern Affairs Canada Yellowknife, NT August 2001 SUMMARY In May of 1996 approval was granted and funding awarded by the West Kitikmeot Slave Study Society (WKSS) for a project to initiate research and information dissemination on eskers in the Slave Geological Province. -

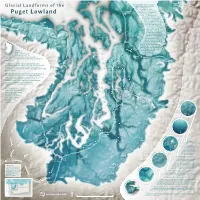

Glacial Landforms of the Puget Lowland

Oak Harbor i t S k a g Sauk Suiattle Suiattle River B a y During the advance and retreat of Indian Reservation Glacial Landforms of the the Puget lobe, drainages around the ice sheet were blocked, forming multiple proglacial Camano Island Stillaguamish lakes. The darker colors on this Indian map indicate lower elevations, Reservation Puget Lowland and show many of these t S Arlington Spi ss valleys. The Stillaguamish, e a en P g n o Snohomish, Snoqualmie, and Striped Peak u r D r Hook a Puyallup River valleys all once t z US Interstate 5 Edi Sauk River Lower Elwha t S contained proglacial lakes. Klallam o u s There are many remnants of Indian g Port a Reservation US Highway 101 Jamestown Townsend a n these lakes left today, such as S’Klallam A Quimper Peninsula Port Angeles Indian Lake Washington and Lake d Reservation Sequim P Sammamish, east of Seattle. o m H P Miller Peninsula r t o a S T l As the Puget lobe retreated, i m Tulalip e o s w McDonald Mountain q r e Indian lake outflows, glacial D n s u i s s s Reservation i c e a m o a H S. F. Stillaguamish River v n meltwater, and glacial outburst e d a g Marysville B r B l r e a y a b flooding all contributed to y o y t Elwha River B r dozens of channels that flowed y a y southwest to the Chehalis River Round Mountain Lookout Hill Lake Stevens I Whidbey Island at the southwest corner of this n d map. -

Fjord Oceanographic Processes in Glacier Bay, Alaska

Fjord Oceanographic Processes in Glacier Bay, Alaska Philip N. Hooge and Elizabeth Ross Hooge Prepared for the National Park Service, Glacier Bay National Park USGS-Alaska Science Center Glacier Bay Field Station P.O. Box 140 Gustavus, AK 99826-0140 March 2002 Fjord Oceanographic Processes in Glacier Bay, Alaska Philip N. Hooge Elizabeth Ross Hooge Prepared for the National Park Service, Glacier Bay National Park USGS – Alaska Science Center Glacier Bay Field Station P.O. Box 140 Gustavus, AK 99826-0140 March 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary..................................................................3 II. Fjord Oceanography of Glacier Bay, Alaska .....................7 Introduction........................................................................................... 7 Study Site and Methods.................................................................... 10 Results ............................................................................................... 14 Discussion.......................................................................................... 24 Literature Cited .................................................................................. 38 Figures ............................................................................................... 44 III. Oceanographic Data Resources At Glacier Bay.............83 IV. Resource Needs For An Oceanographic Monitoring Program At Glacier Bay ...................................................88 V. Proposed Future Oceanographic Research .....................91