Identifying and Documenting Vernal Pools in New Hampshire 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skyline Park Teacher's Guide Glossary

Skyline Park Teacher’s Guide Cfwep.Org • Clark Fork Watershed Education Program Skyline Park • Butte, Montana Skyline Park Teacher’s Guide Table of Contents Chapter I. Introduction and Welcome 1. Overview of Skyline Park 2. Map of Skyline Park 3. How to use this Guide and the Activities II. About the NGSS and Guide Alignment 1. Background of NGSS and the K-12 Framework 2. Skyline Park Guide and the Montana Content Standards for Science Instruction III. Building Your Content Knowledge 1. Site History 2. Habitat Types of Skyline Park 3. Pond Life 4. Water Quality 5. Stormwater 6. Seed Pod Islands and Pollinators 7. Geology and Soils 8. Restoration IV. Activities 1. Science Note Booking 1.1: Science Note Booking About Skyline Park 2. History 2.1: Write Your Own History for this Site 2.2: Create a Timeline for this Area 3. Mapping the Skyline Park Site 3.1: Where is That?: Mapping the Skyline Park Site 4. Pond Life – Microbes 4.1: Wanderers, Drifters and Floaters, Oh My! 5. Pond Life – Aquatic Macroinvertebrates 2 Skyline Park Teacher’s Guide 5.1-Part 1: What’s That Squirming and Swimming in the Water? Collection and Identification of Pond Macroinvertebrates 5.1-Part 2: What are Those Macroinvertebrates Telling Us? Aquatic Macros as Biological Indicators 5.2: Who's My Mommy? Matching Aquatic Insect Young with their Adult Form 6. Pond Life – Terrestrial Animals 6.1: Crunch Game! The Aquatic Food Chain Game 7. Water Quality 7.1, Option 1: What Life Can This Water Support? Water Quality - WWMD Kits and Data Upload 7.1, Option 2: Water Quality – Vernier Lab Quest Units and Probes 8. -

Fig. Ap. 2.1. Denton Tending His Fairy Shrimp Collection

Fig. Ap. 2.1. Denton tending his fairy shrimp collection. 176 Appendix 1 Hatching and Rearing Back in the bowels of this book we noted that However, salts may leach from soils to ultimately if one takes dry soil samples from a pool basin, make the water salty, a situation which commonly preferably at its deepest point, one can then "just turns off hatching. Tap water is usually unsatis- add water and stir". In a day or two nauplii ap- factory, either because it has high TDS, or because pear if their cysts are present. O.K., so they won't it contains chlorine or chloramine, disinfectants always appear, but you get the idea. which may inhibit hatching or kill emerging If your desire is to hatch and rear fairy nauplii. shrimps the hi-tech way, you should get some As you have read time and again in Chapter 5, guidance from Brendonck et al. (1990) and temperature is an important environmental cue for Maeda-Martinez et al. (1995c). If you merely coaxing larvae from their dormant state. You can want to see what an anostracan is like, buy some guess what temperatures might need to be ap- Artemia cysts at the local aquarium shop and fol- proximated given the sample's origin. Try incu- low directions on the container. Should you wish bation at about 3-5°C if it came from the moun- to find out what's in your favorite pool, or gather tains or high desert. If from California grass- together sufficient animals for a study of behavior lands, 10° is a good level at which to start. -

Phylogenetic Analysis of Anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) Inferred from Nuclear 18S Ribosomal DNA (18S Rdna) Sequences

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 25 (2002) 535–544 www.academicpress.com Phylogenetic analysis of anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) inferred from nuclear 18S ribosomal DNA (18S rDNA) sequences Peter H.H. Weekers,a,* Gopal Murugan,a,1 Jacques R. Vanfleteren,a Denton Belk,b and Henri J. Dumonta a Department of Biology, Ghent University, Ledeganckstraat 35, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium b Biology Department, Our Lady of the Lake University of San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78207, USA Received 20 February 2001; received in revised form 18 June 2002 Abstract The nuclear small subunit ribosomal DNA (18S rDNA) of 27 anostracans (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) belonging to 14 genera and eight out of nine traditionally recognized families has been sequenced and used for phylogenetic analysis. The 18S rDNA phylogeny shows that the anostracans are monophyletic. The taxa under examination form two clades of subordinal level and eight clades of family level. Two families the Polyartemiidae and Linderiellidae are suppressed and merged with the Chirocephalidae, of which together they form a subfamily. In contrast, the Parartemiinae are removed from the Branchipodidae, raised to family level (Parartemiidae) and cluster as a sister group to the Artemiidae in a clade defined here as the Artemiina (new suborder). A number of morphological traits support this new suborder. The Branchipodidae are separated into two families, the Branchipodidae and Ta- nymastigidae (new family). The relationship between Dendrocephalus and Thamnocephalus requires further study and needs the addition of Branchinella sequences to decide whether the Thamnocephalidae are monophyletic. Surprisingly, Polyartemiella hazeni and Polyartemia forcipata (‘‘Family’’ Polyartemiidae), with 17 and 19 thoracic segments and pairs of trunk limb as opposed to all other anostracans with only 11 pairs, do not cluster but are separated by Linderiella santarosae (‘‘Family’’ Linderiellidae), which has 11 pairs of trunk limbs. -

Disappearing Kettle Ponds Reveal a Drying Kenai Peninsula by Ed Berg

Refuge Notebook • Vol. 3, No. 38 • October 12, 2001 Disappearing kettle ponds reveal a drying Kenai Peninsula by Ed Berg A typical transect starts at the forest edge, passes through a grass (Calamagrostis) zone, into Sphagnum peat moss, and then into wet sedges, sometimes with pools of standing water, and then back through these same zones on the other side of the kettle. Three of the four kettles we surveyed this summer were quite wet in the middle (especially after the July rains), and we had to wear hip boots. These plots can be resurveyed in future decades and, if I am correct, they will show a succession of drier and drier plants as the water table drops lower and lower, due to warmer summers and increased evap- Photo of a kettle pond by the National Park Service. otranspiration. If I am wrong, and the climate trend turns around toward cooler and wetter, these plots will When the glaciers left the Soldotna-Sterling area be under water again, as they were on the old aerial some 14,000 years ago, the glacier fronts didn’t re- photos. cede smoothly like their modern descendants, such as By far the most striking feature that we have Portage or Skilak glaciers. observed in the kettles is a band of young spruce Rather, the flat-lying ice sheets broke up into nu- seedlings popping up in the grass zones. These merous blocks, which became partially buried in hilly seedlings can form a halo around the perimeter of a moraines and flat outwash plains. In time these gi- kettle. -

Vernal Pool Fairy Shrimp (Branchinecta Lynchi)

Invertebrates Vernal Pool Fairy Shrimp (Branchinecta lynchi) Vernal Pool Fairy Shrimp (Brachinecta lynchi) Status State: Meets the requirements as a “rare, threatened, or endangered species” under CEQA Federal: Threatened Critical Habitat: Designated 2006 (USFWS 2006) Population Trend Global: Declining due to habitat loss and fragmentation (Eriksen and Belk 1999) State: As above Within Inventory Area: Unknown Data Characterization The location database for the vernal pool fairy shrimp (Brachinecta lynchi) within the inventory area includes 6 records from 1993, 1997, and 1999. The majority of locations are vernal pools within non-native grassland. Other natural and artificial habitats have a high probability of being occupied by additional populations of the vernal pool fairy shrimp throughout the grassland habitats within the ECCC HCP/NCCP inventory area. Beyond the original description (Eng et al. 1990), a scanning electron micrograph of the cyst (resting egg) (Hill and Shepard 1997), and some generalized natural history data (Helm 1997), no peer-reviewed technical literature has been published concerning the vernal pool fairy shrimp. Eriksen and Belk (1999) presented a brief discussion of the vernal pool fairy shrimp and provided a distribution map. Range The vernal pool fairy shrimp is found from Jackson County near Medford, Oregon, throughout the Central Valley, and west to the central Coast Ranges. Isolated southern populations occur on the Santa Rosa Plateau and near Rancho California in Riverside County (Eng et al.1990, Eriksen -

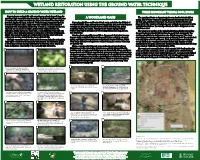

Wetland Restoration USING the Ground Water TECHNIQUE

Wetland ResTORATION USING THE Ground water TECHNIQUE How to build a ground water wetland three important vernal pool zones A ground water wetland fills with water the way a hand-dug well does, by exposing a high water table near the surface. Check for a high water table near a woodland oasis The vernal pool basin or depression is the area that floods in the fall or the center of a potential restoration site. Dig a hole at least 3 feet deep with a spring. This is where vernal pool amphibians and invertebrates breed and post-hole digger, soil auger, or shovel. Watch for water seeping into the hole A vernal pool is like a small oasis of food, water, and shelter for all kinds of lay their eggs, and their young hatch out, feed, and develop (Brown and from the bottom and sides. A high water table will fill the hole partially or woodland wildlife. Large game species such as turkeys, deer, and bears frequent Jung, 2005). The vernal pool basin is the core wetland area protected by state completely with water; listen for the slurp of water as a soil auger is removed. vernal pools, along with a variety of other wildlife including bats, ducks, and federal regulations. The vernal pool basin should be designated as a ‘no Clay soils are not needed to build a ground water wetland because the songbirds, turtles, and snakes. Vernal pools are unique among wetlands disturbance zone.’ depression simply exposes the water table. A seasonally high water table can because they support specialized pool-breeding salamanders, frogs, insects, The vernal pool envelope is the upland habitat immediately surrounding be hard to detect during the summer or any period of drought (Biebighauser, and crustaceans. -

Persistence of Branchinecta Paludosa (Anostraca) in Southern Wyoming, with Notes on Zoogeography

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. JOURNAL OF CRUSTACEAN BIOLOGY, 13(1): 184-189, 1993 PERSISTENCE OF BRANCHINECTA PALUDOSA (ANOSTRACA) IN SOUTHERN WYOMING, WITH NOTES ON ZOOGEOGRAPHY James F. Saunders III, Denton Belk, and Richard Dufford ABSTRACT The fairy shrimp Branchinectapaludosa is a persistentresident of aestival ponds at high elevation in the Medicine Bow Mountains of southernWyoming. These populationsare far removed from the Arctic tundrahabitat that typifiesthe distributionof the species, and appear to representthe southern margin of the range in North America. All of the records for the northernUnited States and southernCanada appear to lie along the CentralFlyway that is a major migrationroute for waterfowland shorebirdsthat nest in the Arctic. Passive dispersal probablyprovides for frequentcolonization of marginalhabitats and gene flow to established populations. The fairy shrimp Branchinectapaludosa have been deposited in the University of (Muller)is widely distributedin the circum- Colorado Museum (UCM 2192, 2193, polar tundra of the Holarctic region (Vek- 2194). The Snowy Range is an axial rem- hoff, 1990). In Europe, it occurs chiefly at nant which rises about 300 m above the latitudes above 60?N, but there are isolated surrounding Medicine Bow Mountains recordsfrom the High Tatra Mountains on (Houston and others, 1978). The ponds are the borderbetween Czechoslovakiaand Po- mainly in the upperTelephone Creek drain- land at about 49?N (Brtek, 1976). Records age at elevations of 3,200-3,350 m. Most for Russia are typically along the Arctic of the ponds are underlainby the Nash Fork margin, but include the southern tip of the formation (Houston and others, 1978), and Kamchatka Peninsula at 52?N (Linder, the characteristicmetadolomite is present 1932). -

Hogback Trail Greenfield State Park Greenfield, New Hampshire

Hogback Trail Greenfield State Park Greenfield, New Hampshire Self-Guided Hike 1. The Hogback Trail is 1.2 miles long and relatively flat. It will take you approximately 45 minutes to go around the pond. As you walk, keep an eye out for the abundant wildlife and unique plants that are in this secluded area of the park. Throughout the trail, there are numbered stations that correspond to this guide and benches to rest upon. Practice “Leave No Trace” on your hike; Take only photographs, leave only footprints. 2. Hogback Pond is a glacial kettle pond formed when massive chunks of Stop #5: ridge is an example of glacial esker ice were buried in the sand, then slowly melted leaving a huge depression in the landscape that eventually filled with water. Kettle ponds generally have no streams running into them or out of them, resulting in a still body of water. Water in the pond is replenished by rain and is acidic, prohibiting many common wetland species from flourishing. 3. The blueberry bushes around Hogback Pond and throughout Greenfield State Park are two species; low-bush and high-bush. Many animals such as Black Bear and several species of birds seek out these berries as an important summer food source. Between Stops #2 & 3: example of unique vegetation found on kettle ponds 4. The Eastern Hemlocks that you see around you are one of the several varieties of evergreen that grow around Hogback Pond. This slow- growing, long-lived tree grows well in the shade. They have numerous short needles spreading directly from the branches in one flat layer. -

Leaf Litter Decomposition in Vernal Pools of a Central Ontario Mixedwood Forest

Leaf Litter Decomposition in Vernal Pools of a Central Ontario Mixedwood Forest by Kirsten Verity Otis A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Kirsten V. Otis, July, 2012 ABSTRACT LEAF LITTER DECOMPOSITION IN VERNAL POOLS OF A CENTRAL ONTARIO MIXEDWOOD FOREST Kirsten V. Otis Advisors: University of Guelph, 2012 Dr. Jonathan Schmidt Dr. Shelley Hunt Vernal pools are small, seasonally filling wetlands found throughout forests of north eastern North America. Vernal pools have been proposed as potential 'hot spots' of carbon cycling. A key component of the carbon cycle within vernal pools is the decomposition of leaf litter. I tested the hypothesis that leaf litter decomposition is more rapid within vernal pools than the adjacent upland. Leaf litter mass losses from litterbags incubated in situ within vernal pools and adjacent upland habitat were measured periodically over one year and then again after two years. The experiment was carried out at 24 separate vernal pools, over two replicate years. This is a novel degree of replication in studies of decomposition in temporary wetlands. Factors influencing decomposition, such as duration of flooding, water depth, pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen were measured. Mass loss was greater within pools than adjacent upland after 6 months, equal after 12 months, and lower within pools than adjacent upland after 24 months. This evidence suggests that vernal pools of Central Ontario are 'hot spots' of decomposition up to 6 months, but not after 12 and 24 months. In the long term, vernal pools may reduce decomposition rates, compared to adjacent uplands. -

Biological Resources Assessment the Ranch ±530- Acre Study Area City of Rancho Cordova, California

Biological Resources Assessment The Ranch ±530- Acre Study Area City of Rancho Cordova, California Prepared for: K. Hovnanian Homes October 13, 2017 Prepared by: © 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Project Description ........................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Regulatory Framework ........................................................................................................ 2 2.1. Federal Regulations .......................................................................................................... 2 2.1.1. Federal Endangered Species Act ............................................................................... 2 2.1.2. Migratory Bird Treaty Act ......................................................................................... 2 2.1.3. The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act ............................................................... 2 2.2. State Jurisdiction .............................................................................................................. 3 2.2.1. California Endangered Species Act ........................................................................... 3 2.2.2. California Department of Fish and Game Codes ...................................................... 3 2.2.3. Native Plant Protection Act ..................................................................................... -

Portsmouth Vernal Pool Inventory

Portsmouth Vernal Pool Inventory Prepared for: City of Portsmouth, NH Conservation Commission Prepared by: 122 Mast Road, Suite 6, Lee, NH 03861 in cooperation with The City of Portsmouth Planning Department and October 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary II. Vernal Pools Defined III. Methodology IV. Vernal Pool Documentation Sheet V. Findings and Focus Area Summaries VI. Focus Area and Pool Location Maps VII. References Appendices A. Vernal Pool Documentation Sheets B. Proposed Revisions to Wetland Protection Regulations C. Aerial Photo Field Sheets City of Portsmouth Vernal Pool Inventory Report Page 1 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY West Environmental, Inc. (WEI) conducted a city-wide Vernal Pool Inventory to locate, document and map vernal pools in Portsmouth. This effort was coordinated with the Portsmouth Planning Department and Conservation Commission to help the City of Portsmouth in vernal pool identification and mapping. The goal of this project was to locate isolated wetlands that provide vernal pool habitat. Currently the City of Portsmouth’s wetland regulations exempt wetlands less than 5,000 square feet from the local 100’ buffer zone. This study identified smaller wetlands which have the potential to provide vernal pool habitat that may deserve the 100 foot buffer protection. It should be noted that vernal pool habitat can exist in a variety of freshwater wetlands including larger red maple swamps. These areas were also mapped when encountered. A field workshop was held for the Conservation Commission members to give them hands-on training in vernal pool ecology. The results of this Vernal Pool Inventory were presented to the Portsmouth Conservation Commission in July of 2008. -

Des Moines Lobe Retreated North- What It Means to Be Minnesotan

Route Map Geology of the Carleton College Esri, HERE, DeLorme, MapmyIndia, © OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS ¯ user community 1 Cannon River Cowling Arboretum 2 Glacial Landscapes 3 Glacial Erratics 4 Local Bedrock A Guided Tour 5 Kettle Hole Marsh College BoundaryH - Back IA Parking Glacial Erratic Cannon River Tour Route Other Trails 0250 500 1 000 Feet, 5 HWY 3 4 LOWER ARBORETUM 3 2 H IA 1 Arb Office HWY 19 UPPER Tunnel IA ARBORETUM under Hwy 19 Lower Lyman Recreation IA Center HALL AVE HALL West IA Gym Library Published 5/2016 Product of the Carleton College Cowling Arboretum. For more information visit our website: apps.carleton.edu/campus/arb or contact us at (507)-222-4543 Introduction Hello and welcome to Carleton College’s Cowling Arboretum. This 1 800 acre natural area, owned and managed by Carleton, has long been one of the most beloved parts of Carleton for students, faculty and community members alike. Although the Arb is best known for its prairie ecosystem, an amazing history full of thundering riv- ers, massive glaciers, and the journeys of massive boulders lies just below the surface. This geologic history of the Arb is a fascinating story and one that you can experience for yourself by following this 2 self-guided tour. I hope it’s a beautiful day for a walk hope and that you enjoy learning about the geology of the Arb as much as I did. The route for this tour is about three miles long and will take you 1-2 hours to complete, depending on your walking speed.