Nishida Kitarō's Logic of Absolutely Contradictory Identity and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goethe, the Japanese National Identity Through Cultural Exchange, 1889 to 1989

Jahrbuch für Internationale Germanistik pen Jahrgang LI – Heft 1 | Peter Lang, Bern | S. 57–100 Goethe, the Japanese National Identity through Cultural Exchange, 1889 to 1989 By Stefan Keppler-Tasaki and Seiko Tasaki, Tokyo Dedicated to A . Charles Muller on the occasion of his retirement from the University of Tokyo This is a study of the alleged “singular reception career”1 that Goethe experi- enced in Japan from 1889 to 1989, i. e., from the first translation of theMi gnon song to the last issues of the Neo Faust manga series . In its path, we will high- light six areas of discourse which concern the most prominent historical figures resp. figurations involved here: (1) the distinct academic schools of thought aligned with the topic “Goethe in Japan” since Kimura Kinji 木村謹治, (2) the tentative Japanification of Goethe by Thomas Mann and Gottfried Benn, (3) the recognition of the (un-)German classical writer in the circle of the Japanese national author Mori Ōgai 森鴎外, as well as Goethe’s rich resonances in (4) Japanese suicide ideals since the early days of Wertherism (Ueruteru-zumu ウェル テルヅム), (5) the Zen Buddhist theories of Nishida Kitarō 西田幾多郎 and D . T . Suzuki 鈴木大拙, and lastly (6) works of popular culture by Kurosawa Akira 黒澤明 and Tezuka Osamu 手塚治虫 . Critical appraisal of these source materials supports the thesis that the polite violence and interesting deceits of the discursive history of “Goethe, the Japanese” can mostly be traced back, other than to a form of speech in German-Japanese cultural diplomacy, to internal questions of Japanese national identity . -

PUBLICATION of SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER Vol. XXXVI No. 1 Spring I Summer 2002 CONTENTS

PUBLICATION OF SAN FRANCISCO ZEN CENTER Vol. XXXVI No. 1 Spring I Summer 2002 CONTENTS TALKS 3 The Gift of Zazen BY Shunryu Suzuki-roshi 16 Practice On and Off the Cushion BY Anna Thom 20 The World Is Vast and Wide BY Gretel Ehrlich 36 An Appropriate Response BY Abbess Linda Ruth Cutts POETRY AND ART 4 Kannon in Waves BY Dan Welch (See also front cover and pages 9 and 46) 5 Like Water BY Sojun Mel Weitsman 24 Study Hall BY Zenshin Philip Whalen NEWS AND FEATURES 8 orman Fischer Revisited AN INTERVIEW 11 An Interview with Annie Somerville, Executive Chef of Greens 25 Projections on an Empty Screen BY Michael Wenger 27 Sangha-e! 28 Through a Glass, Darkly BY Alan Senauke 42 'Treasurer's Report on Fiscal Year 2002 DY Kokai Roberts 2 covet WNO eru 111 -ASSl\ll\tll.,,. o..N WEICH The Gi~ of Zazen Shunryu Suzuki Roshi December 14, 1967-Los Altos, California JAM STILL STUDYING to find out what our way is. Recently I reached the conclusion that there is no Buddhism or Zen or anythjng. When I was preparing for the evening lecture in San Francisco yesterday, I tried to find something to talk about, but I couldn't; then I thought of the story 1 was told in Obun Festival when I was young. The story is about water and the people in Hell Although they have water, the people in hell cannot drink it because the water burns like fire or it looks like blood, so they cannot drink it. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 17 2015 Special Issue: Fiftieth Anniversary of the Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai Pacific World is an annual journal in English devoted to the dissemination of his- torical, textual, critical, and interpretive articles on Buddhism generally and Shinshu Buddhism particularly to both academic and lay readerships. The journal is distributed free of charge. Articles for consideration by the Pacific World are welcomed and are to be submitted in English and addressed to the Editor, Pacific World, 2140 Durant Ave., Berkeley, CA 94704-1589, USA. Acknowledgment: This annual publication is made possible by the donation of BDK America of Moraga, California. Guidelines for Authors: Manuscripts (approximately twenty standard pages) should be typed double-spaced with 1-inch margins. Notes are to be endnotes with full biblio- graphic information in the note first mentioning a work, i.e., no separate bibliography. See The Chicago Manual of Style (16th edition), University of Chicago Press, §16.3 ff. Authors are responsible for the accuracy of all quotations and for supplying complete references. Please e-mail electronic version in both formatted and plain text, if possible. Manuscripts should be submitted by February 1st. Foreign words should be underlined and marked with proper diacriticals, except for the following: bodhisattva, buddha/Buddha, karma, nirvana, samsara, sangha, yoga. Romanized Chinese follows Pinyin system (except in special cases); romanized Japanese, the modified Hepburn system. Japanese/Chinese names are given surname first, omit- ting honorifics. Ideographs preferably should be restricted to notes. -

Fall 1969 Wind Bell

PUBLICATION OF ZEN •CENTER Volume Vilt Nos. 1-2 Fall 1969 This fellow was a son of Nobusuke Goemon Ichenose of Takahama, the province of Wakasa. His nature was stupid and tough. When he was young, none of his relatives liked him. When he was twelve years old, he was or<Llined as a monk by Ekkei, Abbot of Myo-shin Monastery. Afterwards, he studied literature under Shungai of Kennin Monastery for three years, and gained nothing. Then he went to Mii-dera and studied Tendai philosophy under Tai-ho for. a summer, and gained nothing. After this, he went to Bizen and studied Zen under the old teacher Gisan for one year, and attained nothing. He then went to the East, to Kamakura, and studied under the Zen master Ko-sen in the Engaku Monastery for six years, and added nothing to the aforesaid nothingness. He was in charge of a little temple, Butsu-nichi, one of the temples in Engaku Cathedral, for one year and from there he went to Tokyo to attend Kei-o College for one year and a half, making himself the worst student there; and forgot the nothingness that he had gained. Then he created for himself new delusions, and came to Ceylon in the spring of 1887; and now, under the Ceylon monk, he is studying the Pali Language and Hinayana Buddhism. Such a wandering mendicant! He ought to <repay the twenty years of debts to those who fed him in the name of Buddhism. July 1888, Ceylon. Soyen Shaku c.--....- Ocean Wind Zendo THE KOSEN ANO HARADA LINEAOES IN AMF.RICAN 7.llN A surname in CAI':> andl(:attt a Uhatma heir• .l.incagea not aignilleant to Zen in Amttka arc not gi•cn. -

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California L

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California Last week I posted on my Monkey Mind blog an essay I titled Soto Zen Buddhism in North America: Some Random Notes From a Work in Progress. There I wrote, along with a couple of small digressions and additions I add for this talk: Probably the most important thing here (within our North American Zen and particularly our North American Soto Zen) has been the rise in the importance of lay practice. My sense is that the Japanese hierarchy pretty close to completely have missed this as something important. And, even within the convert Soto ordained community, a type of clericalism that is a sense that only clerical practice is important exists that has also blinded many to this reality. That reality is how Zen practice belongs to all of us, whatever our condition in life, whether ordained, or lay. Now, this clerical bias comes to us honestly enough. Zen within East Asia is project for the ordained only. But, while that is an historical fact, it is very much a problem here. Actually a profound problem here. Throughout Asia the disciplines of Zen have largely been the province of the ordained, whether traditional Vinaya monastics or Japanese and Korean non-celibate priests. This has been particularly so with Japanese Soto Zen, where the myth and history of Dharma transmission has been collapsed into the normative ordination model. Here I feel it needful to note this is not normative in any other Zen context. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Excerpts for Distribution

EXCERPTS FOR DISTRIBUTION Two Shores of Zen An American Monk’s Japan _____________________________ Jiryu Mark Rutschman-Byler Order the book at WWW.LULU.COM/SHORESOFZEN Join the conversation at WWW.SHORESOFZEN.COM NO ZEN IN THE WEST When a young American Buddhist monk can no longer bear the pop-psychology, sexual intrigue, and free-flowing peanut butter that he insists pollute his spiritual community, he sets out for Japan on an archetypal journey to find “True Zen,” a magical elixir to relieve all suffering. Arriving at an austere Japanese monastery and meeting a fierce old Zen Master, he feels confirmed in his suspicion that the Western Buddhist approach is a spineless imitation of authentic spiritual effort. However, over the course of a year and a half of bitter initiations, relentless meditation and labor, intense cold, brutal discipline, insanity, overwhelming lust, and false breakthroughs, he grows disenchanted with the Asian model as well. Finally completing the classic journey of the seeker who travels far to discover the home he has left, he returns to the U.S. with a more mature appreciation of Western Buddhism and a new confidence in his life as it is. Two Shores of Zen weaves together scenes from Japanese and American Zen to offer a timely, compelling contribution to the ongoing conversation about Western Buddhism’s stark departures from Asian traditions. How far has Western Buddhism come from its roots, or indeed how far has it fallen? JIRYU MARK RUTSCHMAN-BYLER is a Soto Zen priest in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. He has lived in Buddhist temples and monasteries in the U.S. -

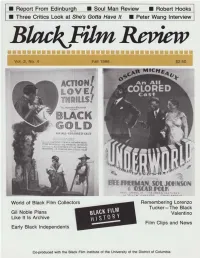

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

Number 3 2011 Korean Buddhist Art

NUMBER 3 2011 KOREAN BUDDHIST ART KOREAN ART SOCIETY JOURNAL NUMBER 3 2011 Korean Buddhist Art Publisher and Editor: Robert Turley, President of the Korean Art Society and Korean Art and Antiques CONTENTS About the Authors…………………………………………..………………...…..……...3-6 Publisher’s Greeting…...…………………………….…….………………..……....….....7 The Museum of Korean Buddhist Art by Robert Turley…………………..…..…..8-10 Twenty Selections from the Museum of Korean Buddhist Art by Dae Sung Kwon, Do Kyun Kwon, and Hyung Don Kwon………………….….11-37 Korean Buddhism in the Far East by Henrik Sorensen……………………..…….38-53 Korean Buddhism in East Asian Context by Robert Buswell……………………54-61 Buddhist Art in Korea by Youngsook Pak…………………………………..……...62-66 Image, Iconography and Belief in Early Korean Buddhism by Jonathan Best.67-87 Early Korean Buddhist Sculpture by Lena Kim…………………………………....88-94 The Taenghwa Tradition in Korean Buddhism by Henrik Sorensen…………..95-115 The Sound of Ecstasy and Nectar of Enlightenment by Lauren Deutsch…..116-122 The Korean Buddhist Rite of the Dead: Yeongsan-jae by Theresa Ki-ja Kim123-143 Dado: The Korean Way of Tea by Lauren Deutsch……………………………...144-149 Korean Art Society Events…………………………………………………………..150-154 Korean Art Society Press……………………………………………………………155-162 Bibliography of Korean Buddhism by Kenneth R. Robinson…...…………….163-199 Join the Korean Art Society……………...………….…….……………………...……...200 About the Authors 1 About the Authors All text and photographs contained herein are the property of the individual authors and any duplication without permission of the authors is a violation of applicable laws. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY THE INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS. Please click on the links in the bios below to order each author’s publications or to learn more about their activities. -

Review Of" Unsui: a Diary of Zen Monastic Life" by E. Nishimura

Swarthmore College Works Religion Faculty Works Religion 10-1-1975 Review Of "Unsui: A Diary Of Zen Monastic Life" By E. Nishimura Donald K. Swearer Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-religion Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Donald K. Swearer. (1975). "Review Of "Unsui: A Diary Of Zen Monastic Life" By E. Nishimura". Philosophy East And West. Volume 25, Issue 4. 495-496. DOI: 10.2307/1398231 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-religion/122 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 495 is, to write a twentieth century Cloud of' Unknowing (a Christian document) by using Buddhism. PAUL WIENPAHL University of California, Santa Barbara Unsui: A Diary of Zen Monastic Life, by Eshin Nishimura, edited by Bardwell L. Smith, drawings by Giei Sa to . Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1973 . In Unsui Eshin Nishimura and Bardwell Smith have put together a thoroughly delightful volume on Zen Buddhist training and monastic life. The book combines ninety-six comic, cartoonlike color drawings by Giei Sato (1920- 1970)- an "ordinary Rinzai Zen temple priest"- with Nishimura's running commentary, and a useful introduction by Bardwell Smith which underlines the paradox of tension and harmony characterizing Zen Buddhist monastic life. Taken as a whole, from its appreciative Foreword by Zenkei Shibayama to its Glossary, the book provides a helpful counterpoint to the standard popular work in this area, D. -

The Koan : Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism

Introduction Koan Tradition: Self-Narrative an d Contemporary Perspective s STEVEN HEINE AND DALE S. WRIGHT Aims The term koa n (C . kung-an, literall y "public cases" ) refer s t o enigmati c an d often shockin g spiritual expressions based o n dialogica l encounters between masters and disciples that were used as pedagogical tools for religious training in th e Ze n (C . Ch'an) Buddhist tradition . Thi s innovative practic e i s one of the best-known and most distinctive elements of Zen Buddhism. Originating in T'ang/Sung China, the use of koans spread t o Vietnam, Korea, an d Japa n and now attracts international attention. What is unique about the koan is the way i n whic h i t i s thought t o embod y th e enlightenmen t experienc e o f th e Buddha an d Ze n masters through a n unbroken lin e of succession. Th e koan was conceived as both the tool by which enlightenment is brought abou t an d an expression of the enlightened mind itself. Koans ar e generally appreciate d today as pithy, epigrammatic, elusiv e utterances that see m to hav e a psycho- therapeutic effec t i n liberatin g practitioner s fro m bondag e t o ignorance , a s well a s fo r th e wa y they ar e containe d i n th e complex , multilevele d literary form o f koan collectio n commentaries . Perhap s n o dimensio n o f Asian reli - gions has attracted s o much interest and attention i n the West, from psycho - logical interpretations and comparative mystical theology to appropriations i n beat poetry and deconstractive literary criticism. -

(LACMA) Hosted Its Ninth Annual Art+Film Gala on Saturday, November 2, 2019, Honoring Artist Betye Saar and Filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón

(Los Angeles, November 3, 2019)—The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) hosted its ninth annual Art+Film Gala on Saturday, November 2, 2019, honoring artist Betye Saar and filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón. Co-chaired by LACMA trustee Eva Chow and actor Leonardo DiCaprio, the evening brought together more than 800 distinguished guests from the art, film, fashion, and entertainment industries, among others. This year’s gala raised more than $4.6 million, with proceeds supporting LACMA’s film initiatives and future exhibitions, acquisitions, and programming. The 2019 Art+Film Gala was made possible through Gucci’s longstanding and generous partnership. Additional support for the gala was provided by Audi. Eva Chow, co-chair of the Art+Film Gala, said, “I’m so happy that we have outdone ourselves again with the most successful Art+Film Gala yet. It was such a joy to celebrate Betye Saar and Alfonso Cuarón’s incredible creativity and passion, while supporting LACMA’s art and film initiatives. I couldn’t be more grateful to Alessandro Michele, Marco Bizzarri, and everyone at Gucci—our invaluable partner since the first Art+Film Gala—and to Anderson .Paak and The Free Nationals for making this evening one to remember.” “I’m deeply grateful to our returning co-chairs Eva Chow and Leonardo DiCaprio for helping us set another Art+Film Gala record,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “We honored two incredibly powerful artistic voices this year. Betye Saar has helped define the genre of Assemblage art for nearly seven decades, and recognition of her as one of the most important and influential artists working today is long overdue.