Dr John Barkham1 Seventeenth-Century Antiquary and Numismatist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of people who have shaped British history, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. The Oxford DNB (ODNB) currently includes the life stories of over 60,000 men and women who died in or before 2017. Over 1,300 of those lives contain references to Coventry, whether of events, offices, institutions, people, places, or sources preserved there. Of these, over 160 men and women in ODNB were either born, baptized, educated, died, or buried there. Many more, of course, spent periods of their life in Coventry and left their mark on the city’s history and its built environment. This survey brings together over 300 lives in ODNB connected with Coventry, ranging over ten centuries, extracted using the advanced search ‘life event’ and ‘full text’ features on the online site (www.oxforddnb.com). The same search functions can be used to explore the biographical histories of other places in the Coventry region: Kenilworth produces references in 229 articles, including 44 key life events; Leamington, 235 and 95; and Nuneaton, 69 and 17, for example. Most public libraries across the UK subscribe to ODNB, which means that the complete dictionary can be accessed for free via a local library. Libraries also offer 'remote access' which makes it possible to log in at any time at home (or anywhere that has internet access). Elsewhere, the ODNB is available online in schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions worldwide. Early benefactors: Godgifu [Godiva] and Leofric The benefactors of Coventry before the Norman conquest, Godgifu [Godiva] (d. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5tv2w736 Author Harkins, Robert Lee Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. -

Source Notes for the Library by Stuart Kells (Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2017)

Source Notes for The Library by Stuart Kells (Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2017) p. 6. ‘My company is gone, so that now I hope to enjoy my selfe and books againe, which are the true pleasures of my life, all else is but vanity and noyse.’: Peter Beal, ‘“My Books are the Great Joy of My Life”. Sir William Boothby, Seventeenth-Century Bibliophile’, in Nicholas Barker (ed.), The Pleasures of Bibliophily, (London & New Castle: British Library/Oak Knoll Press, 2003), p. 285. p. 6. ‘the existence within his dwelling-place of any book not of his own special kind, would impart to him the sort of feeling of uneasy horror which a bee is said to feel when an earwig comes into its cell’: John Hill Burton, The Book-Hunter etc, (Edinburgh & London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1885), p. 21. p. 8. ‘menial and dismal’: Jorge Luis Borges, ‘Autobiographical Essay’, in The Aleph and Other Stories 1933-1969, (London: Picador, 1973), p. 153. p. 8. ‘filled with tears’: Jorge Luis Borges, ‘Autobiographical Essay’, in The Aleph and Other Stories 1933-1969, (London: Picador, 1973), p. 153. p. 8. ‘On that miraculous day, she looked up from reading C. S. Lewis, noticing he had begun to cry. In perfect speech, he told her, “I’m crying because I understand”.’: Elizabeth Hyde Stevens, ‘Borges and $: The parable of the literary master and the coin’, Longreads, June 2016. p. 8: ‘a nightmare version or magnification’: Jorge Luis Borges, ‘Autobiographical Essay’, in The Aleph and Other Stories 1933-1969, (London: Picador, 1973), p. 154. p. 9. -

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 42 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C.H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Verse and Transmutation A Corpus of Middle English Alchemical Poetry (Critical Editions and Studies) By Anke Timmermann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 On the cover: Oswald Croll, La Royalle Chymie (Lyons: Pierre Drobet, 1627). Title page (detail). Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, Chemical Heritage Foundation. Photo by James R. Voelkel. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Timmermann, Anke. Verse and transmutation : a corpus of Middle English alchemical poetry (critical editions and studies) / by Anke Timmermann. pages cm. – (History of Science and Medicine Library ; Volume 42) (Medieval and Early Modern Science ; Volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback : acid-free paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) 1. Alchemy–Sources. 2. Manuscripts, English (Middle) I. Title. QD26.T63 2013 540.1'12–dc23 2013027820 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1872-0684 ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

The Unpublished "Itinerary" of Fynes Moryson (1566

SHAKESPEARE'S EUROPE REVISITED: THE UNPUBLISHED ITINERARY OF FYNES MORYSON (1566 - 1630) by GRAHAM DAVID KEW A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts of The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Volume I The Shakespeare Institute School of English Faculty of Arts The University of Birmingham July 1995 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Synopsis This thesis consists of a transcript and edition of Fynes Moryson's unpublished Itinerary c.1617 - 1625, with introduction, text, annotations, bibliography and index. Moryson was a gentleman traveller whose accounts of journeys undertaken in the 1590s across much of Europe as far as the Holy Land in the Ottoman Empire provide contemporary evidence of secular and religious institutions, ceremonies, customs, manners, and national characteristics. The first part of Moryson's Itinerary was published in 1617. Some of the second part was transcribed in 1903 by Charles Hughes as Shakespeare's Europe, but this is the first transcript and edition of the whole manuscript. The work has involved investigation of the historical, classical and geographical sources available to Moryson, of Elizabethan secretary hand, and of travel writing as a form of primitive anthropology. -

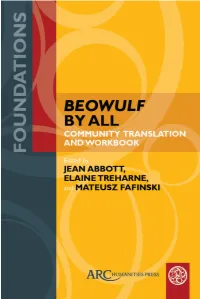

Beowulf by All Community Translation and Workbook

FOUNDATIONS Advisory Board Robert E. Bjork, Arizona State University Alessandra Bucossi, Università Ca’ Foscari, Venezia Chris Jones, University of Canterbury / Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha Sharon Kinoshita, University of California, Santa Cruz Matthew Cheung Salisbury, University of Oxford FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE ONLY BEOWULF BY ALL COMMUNITY TRANSLATION AND WORKBOOK Edited by JEAN ABBOTT, ELAINE TREHARNE, and MATEUSZ FAFINSKI British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. © 2021, Arc Humanities Press, Leeds This work is licensed under Creative Commons licence CCBYNCND 4.0. Permission to use brief excerpts from this work in scholarly and educational works is hereby The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of their part of this work. granted provided that the source is acknowledged. Any use of material in this work that is an exception or limitation covered by Article 5 of the European Union’s Copyright Directive (2001/29/EC) or would be determined to be “fair use” under Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act September 2010 Page 2 or that satisfies the conditions specified in Section 108 of the U.S. Copy right Act (17 USC §108, as revised by P.L. 94553) does not require the Publisher’s permission. ISBN (hardback): 9781641894708 ISBN (paperback): 9781641894715 eISBN (PDF): 9781641894746 www.arc-humanities.org Printed and bound in the UK (by CPI Group [UK) Ltd), USA (by Bookmasters), and elsewhere using print-on-demand technology. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE ONLY CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................... -

St Peter's Cambridge Guide

CHURCH OF ST PETER off Castle Street, Cambridge 1 West Smithfield London EC1A 9EE Tel: 020 7213 0660 Fax: 020 7213 0678 Email: [email protected] £2.50 www.visitchurches.org.uk Registered Charity No. 258612 Spring 2007 off Castle Street, Cambridge CHURCH OF ST PETER by Lawrence Butler (Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, formerly Head of the Department of Archaeology, Leeds University, and archaeological consultant to Lincoln, Sheffield and Wakefield cathedrals) INTRODUCTION The church and churchyard of St Peter offer an oasis of calm amid the rush of commuter traffic along Castle Street leading to Huntingdon and Histon roads and the steady throb of orbital traffic on Northampton Street. The mature limes and horse chestnuts provide a green island closely surrounded by housing, though the names of Honey Hill and Pound Green recall a more rural past. During the spring and early summer it is a colourful haven of wild flowers. This church has always been set in a poor neighbourhood and Castle End has a definite country feel to it. The domestic architecture, whether of the 17th century on either side of Northampton Street, or of more recent building in local style and materials in Honey Hill, all contribute to this rural atmosphere, unlike the grander buildings of the colleges in the centre of the city. In the middle years of the 20th century St Peter’s was known as the Children’s Church, and more recently it has been supported by a loyal band of friends and helpers who have cherished the tranquillity of this building – the smallest medieval church in Front cover: Exterior from the south-east Cambridge. -

Academic Archives: Uberlieferungsbildung

The American Archivist / Vol. 43, No. 4 / Fall 1980 449 Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/43/4/449/2746734/aarc_43_4_23436648670625l1.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 Academic Archives: Uberlieferungsbildung MAYNARD BRICHFORD ARCHIVES—REPOSITORIES AND DOCUMENTS—AND THE ARCHIVISTS who are responsible for them draw their identity from the institutions they serve. Government archivists serve the interests of government and keep the records of governmental activities: war, diplomacy, taxation, legal proceedings, utility regulation, and welfare programs. Business archivists hold records of production, investment, patenting, marketing, and employment. Religious archivists are responsible for the documentation of clerical activities, vital statistics of in- stitutions that record the hatching, matching, and dispatching. Academic archivists retain documentation on teaching, research, public service, and the acculturation of youth. In- stitutions of higher education occupy a unique position of importance and influence in America. A society distinguished for its technology, political institutions, and mass edu- cation needs the continuing scientific examination of its progress and the preparation of a large group of citizens for civic leadership. Academic archivists have a major responsi- bility for Uberlieferungsbildung, the handing down of culture or civilization. The origins of the modern university lie in the medieval university, which has been called the "school of the modern spirit." Charles Haskins stated that "no substitute has been found for the university in its main business, the training of scholars and the main- tenance of the tradition of learning and investigation." Though the early universities drew upon classical culture, the organizational structure is traceable to Bologna, Paris, and Oxford in the middle of the twelfth century. -

The Wanderings and Homes of Manuscripts the Wanderings and Homes of Manuscripts

M.R. JAMES, The Wanderings and Homes of Manuscripts, London (1919) HELPS FOR STUDENTS OF HISTORY. No. 17 EDITED BY C. JOHNSON, M.A., AND J.P. WHITNEY, D.D., D.C.L. THE WANDERINGS AND HOMES OF MANUSCRIPTS BY M. R. JAMES, LITT.D, F.B.A PROVOST OF ETON SOMETIME PROVOST OF KING'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE LONDON SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE NEW YORK : THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1919 |p3 THE WANDERINGS AND HOMES OF MANUSCRIPTS The Wanderings and Homes of Manuscripts is the title of this book. To have called it the survival and transmission of ancient literature would have been pretentious, but not wholly untruthful. Manuscripts, we all know, are the chief means by which the records and imaginings of twenty centuries have been preserved. It is my purpose to tell where manuscripts were made, and how and in what centres they have been collected, and, incidentally, to suggest some helps for tracing out their history. Naturally the few pages into which the story has to be packed will not give room for any one episode to be treated exhaustively. Enough if I succeed in rousing curiosity and setting some student to work in a field in which and immense amount still remains to be discovered. In treating of so large a subject as this----for it is a large one----it is not a bad plan to begin with the particular and get gradually to the general. SOME SPECIMEN PEDIGREES OF MSS. I take my stand before the moderate-sized bookcase which contains the collection of MSS |p4 belonging to the College of Eton, and with due care draw from the shelves a few of the books which have reposed there since the room was built in 1729. -

The Percival J. Baldwin Puritan Collection

The Percival J. Baldwin Puritan Collection Accessing the Collection: 1. Anyone wishing to use this collection for research purposes should complete a “Request for Restricted Materials” form which is available at the Circulation desk in the Library. 2. The materials may not be taken from the Library. 3. Only pencils and paper may be used while consulting the collection. 4. Photocopying and tracing of the materials are not permitted. Classification Books are arranged by author, then title. There will usually be four elements in the call number: the name of the collection, a cutter number for the author, a cutter number for the title, and the date. Where there is no author, the cutter will be A0 to indicate this, to keep filing in order. Other irregularities are demonstrated in examples which follow. BldwnA <-- name of collection H683 <-- cutter for author O976 <-- cutter for title 1835 <-- date of publication Example. A book by the author Thomas Boston, 1677-1732, entitled, Human nature in its fourfold state, published in 1812. BldwnA B677 <-- cutter for author H852 <-- cutter for title 1812 <-- date of publication Variations in classification scheme for Baldwin Puritan collection Anonymous works: BldwnA A0 <---- Indicates no author G363 <---- Indicates title 1576 <---- Date Bibles: BldwnA B524 <---- Bible G363 <---- Geneva 1576 <---- Date Biographies: BldwnA H683 <---- cuttered on subject's name Z5 <---- Z5 indicates biography R633Li <---- cuttered on author's name, 1863 then first two letters of title Letters: BldwnA H683 <----- cuttered -

Church and People in Interregnum Britain

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London Press ***** Publication details: Church and People in Interregnum Britain Edited by Fiona McCall https://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/ church-and-people-in-interregnum-britain DOI: 10.14296/2106.9781912702664 ***** This edition published in 2021 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-912702-66-4 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses Church and people in interregnum Britain New Historical Perspectives is a book series for early career scholars within the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Books in the series are overseen by an expert editorial board to ensure the highest standards of peer-reviewed scholarship. Commissioning and editing is undertaken by the Royal Historical Society, and the series is published under the imprint of the Institute of Historical Research by the University of London Press. The series is supported by the Economic History Society and the Past and Present Society. Series co-editors: Heather Shore (Manchester Metropolitan University) and Elizabeth Hurren (University of Leicester) Founding co-editors: Simon Newman (University -

George Abbot 1562-1633 Archbishop of Canterbury

English Book Owners in the Seventeenth Century: A Work in Progress Listing How much do we really know about patterns and impacts of book ownership in Britain in the seventeenth century? How well equipped are we to answer questions such as the following?: • What was a typical private library, in terms of size and content, in the seventeenth century? • How does the answer to that question vary according to occupation, social status, etc? • How does the answer vary over time? – how different are ownership patterns in the middle of the century from those of the beginning, and how different are they again at the end? Having sound answers to these questions will contribute significantly to our understanding of print culture and the history of the book more widely during this period. Our current state of knowledge is both imperfect, and fragmented. There is no directory or comprehensive reference source on seventeenth-century British book owners, although there are numerous studies of individual collectors. There are well-known names who are regularly cited in this context – Cotton, Dering, Pepys – and accepted wisdom as to collections which were particularly interesting or outstanding, but there is much in this area that deserves to be challenged. Private Libraries in Renaissance England and Books in Cambridge Inventories have developed a more comprehensive approach to a particular (academic) kind of owner, but they are largely focused on the sixteenth century. Sears Jayne, Library Catalogues of the English Renaissance, extends coverage to 1640, based on book lists found in a variety of manuscript sources. Evidence of book ownership in this period is manifested in a variety of ways, which need to be brought together if we are to develop that fuller picture.