Ethnographies of Waiting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horizontal Reciprocal Radicalization a Comparative Analysis of Two Cases in a Norwegian Context

Candidate number: 109 Horizontal Reciprocal Radicalization A comparative analysis of two cases in a Norwegian context Philippe Aleksander Orban UNIVERSITY OF BERGEN Department of Comparative Politics Master’s thesis in Comparative Politics Course code: Sampol 350 Word count: 35 597 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………. 6 2. Theoretical framework ……………………………………………………………............ 9 2.1. Radicalization: literature and definitions…………………………………………….. 9 2.1.1. Clarifying non-violent actions……………………………………………….... 11 2.1.2. A sidenote on political violence………………………………………………. 12 2.2. Ideology……………………………………………………………………………… 13 2.2.1. Radicals……………………………………………………………………….. 14 2.2.2. The radical right…………………………………………………………......... 13 2.2.3. Radical Islamism……………………………………………………………… 15 2.3. The process of radicalization……………………………………………………....... 17 2.3.1. Social psychology…………………………………………………………….. 18 2.3.2. Social Movement Theory…………………………………………………….. 18 2.4. The concept: Cumulative Extremism……………………………………………….. 20 2.5. Understanding Cumulative Extremism trough Social Movement Theory………….. 22 2.6. Cumulative Extremism: conceptual disagreement………………………………….. 24 2.7. Cumulative Extremism: Pathways of influence…………………………………….. 24 2.7.1. Non-violent interactions.................................................................................... 25 2.7.2. Violent interactions........................................................................................... 27 2.8. Cumulative Extremism revised.................................................................................. -

Squatted Social Centres in England and Italy in the Last Decades of the Twentieth Century

Squatted social centres in England and Italy in the last decades of the twentieth century. Giulio D’Errico Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Department of History and Welsh History Aberystwyth University 2019 Abstract This work examines the parallel developments of squatted social centres in Bristol, London, Milan and Rome in depth, covering the last two decades of the twentieth century. They are considered here as a by-product of the emergence of neo-liberalism. Too often studied in the present tense, social centres are analysed here from a diachronic point of view as context- dependent responses to evolving global stimuli. Their ‗journey through time‘ is inscribed within the different English and Italian traditions of radical politics and oppositional cultures. Social centres are thus a particularly interesting site for the development of interdependency relationships – however conflictual – between these traditions. The innovations brought forward by post-modernism and neo-liberalism are reflected in the centres‘ activities and modalities of ‗social‘ mobilisation. However, centres also voice a radical attitude towards such innovation, embodied in the concepts of autogestione and Do-it-Yourself ethics, but also through the reinstatement of a classist approach within youth politics. Comparing the structured and ambitious Italian centres to the more informal and rarefied English scene allows for commonalities and differences to stand out and enlighten each other. The individuation of common trends and reciprocal exchanges helps to smooth out the initial stark contrast between local scenes. In turn, it also allows for the identification of context- based specificities in the interpretation of local and global phenomena. -

Cadenza Generalized Political Activism

15 Schengen, Alta, The Mass Action of the Police, and a Summit in the EU Four relatively “modern” events have taken place in my life which have changed my work from an emphasis on prisons and criminal policy to Cadenza generalized political activism. Such events have always been there and been woven into my initiatives in criminal policy, but the four initiatives to be discussed below have made such an impression on me that I find it A Professional Autobiography necessary to tell a little more about them. I was in a sense dragged into them, one by one, and they ended as four major “columns” in my later life. The first event was the development of the Schengen arrangement within the EU. The Schengen arrangement has a long history, and goes back to the years right after World War II. The Schengen arrangement, which today is falling more or less apart, may possibly be rebuilt in the Thomas Mathiesen future. I took part in it from the outside with a long series of newspaper with the assistance of articles and at a number of meetings in Norway and elsewhere. The Schengen arrangement is a key factor in the development of the EU. To be Snorre Smári Mathiesen sure, my country Norway is not a member of the EU, but economically and otherwise definitely tied to it. Norway was and is therefore in practice an EU-member, though without formal decision-making power. In connection with Schengen I have written something about my two children, two twin boys, because they partly belong to that period. -

Mapping of Cultural and Creative Spaces

Mapping of European cultural and creative spaces Trans Europe Halles and Avril Meehan January 2020 Commissioned by Cultural and Creative Spaces and Cities www.spacesandcities.com Country City Name Type of Space Website Albania Tirana 1023 Betahaus | Tirana Creative Hub http://new.betahaus.al Albania Tirana Tulla Culture Center Cultural Centre https://www.facebook.com/tullacenter/?fref=ts Albania Tirana Ekphrasis Studio Cultural Centre https://ekphrasisstudio.com/ Andorra ANDORRA, 44500 CELAN Cultural Centre http://www.celandigital.com/ Andorra Andorra La Vella, AD500 Cineclub de les Valls Cultural Centre https://associacions.andorralavella.ad/cineclub? fbclid=IwAR3Sl84QPhoTne9FANjx6p1ikCVH1_oJKOeoy8O N3K_QST4yBXEN01Bk5Mk Armenia Yerevan 0020 Armenian Centre for Contemporary Cultural Centre http://www.accea.info/en Experimental Art - NPAK Armenia Yerevan 0020 Mask Art Center Cultural Centre https://www.facebook.com/dimakarvestikentron/ Armenia 0010 Yerevan ACCEA Creative Hub https://www.accea.info Austria 1020 Vienna Schraubenfabrik Coworking Co-working Space http://www.schraubenfabrik.at Austria 1030 Vienna Rochus Park Co-working Space http://www.rochuspark.at Austria 1070 Vienna Loffice Wien Co-working Space https://wien.lofficecoworking.com Austria 8020 Graz MANAGERIE Creative Hub http://www.managerie.at/ Austria 5020 Salzburg Coworking Salzburg Co-working Space https://coworkingsalzburg.com Austria 4040 Linz Ars Electronica Creative Hub https://ars.electronica.art Austria Vienna 1160 Brunnenpassage Cultural Centre www.brunnenpassage.at -

Punk and Anarchist Squats in Poland

Punk and Anarchist Squats in Poland Donaghey, J. (2017). Punk and Anarchist Squats in Poland. Trespass, 1, 4-35. https://www.trespass.network/?p=722&lang=en Published in: Trespass Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2017 the authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:04. Oct. 2021 Trespass Journal Article: Punk and Anarchist Squats in Poland Volume 1 2017 www.trespass.network Punk and Anarchist Squats in Poland Jim Donaghey Abstract Squats are of notable importance in the punk scene in Poland, and these spaces are a key aspect of the relationship between anarchism and punk. -

Massive Welcome Set to Greet Mandela's N. America Tour

Socialist Workers Party TH£ holds 35th convention in Chicago Pages 10-11 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 54/NO. 24 JUNE 22, 1990 $1.25 Massive welcome set to greet Mandela's N. America tour BY RONI McCANN In his speeches to working people and Mandela will also visit Boston June 23; Stadiums, coliseums, and concert shells meetings with government officials around Wlshington, D.C, June 24-26; Atlanta June are reserved around the country; a ticker-tape the world, Mandela has continued to call for 27; Miami and Detroit June 28; Los Angeles parade, freedom march, and airport wel maintenance of economic sanctions against June 29; and Oakland, California, June 30. comes are planned; a tour of an auto plant in the Pretoria regime. Detroit and addresses to trade union conven Mter addressing rallies in Toronto and Another victory against apartheid tions are set-all for the 12-day tour to the Montreal June 18 and 19, Mandela's eight While Mandela was in Paris June 7 another United States, to begin June 20, of Mrican city U.S. tour will begin with an official victory was scored in the fight to abolish National Congress leader Nelson Mandela. apartheid. The ·South African government Hundreds of thousands of people across the Speech by Nelson Mandela, announced that the national state of emer country will be turning out to welcome him. gency law would be lifted the next day in Mandela's visit to the United States is part pages 8 and 9. three offour South African provinces: Trans of a 13-nation world tour, with the first stop vaal, Cape Province, and Orange Free State. -

Ethnographies of Waiting

Ethnographies of Waiting 9781474280280_txt_print.indd 1 02/11/17 9:08 PM Ethnographies of Waiting Doubt, Hope and Uncertainty Edited by Manpreet K. Janeja and Andreas Bandak 9781474280280_txt_print.indd 3 02/11/17 9:08 PM First published 2018 by Bloomsbury Academic Published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © Manpreet K. Janeja, Andreas Bandak and Contributors, 2018 Manpreet K. Janeja and Andreas Bandak have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Editors of this work. The Open Access version of this book, available at www.taylorfrancis.com, has been made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 license. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image © Westend61/Getty Images Typeset by Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 13: 978-1-474-28028-0 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978-1-350-12681-7 (pbk) Contents List of Illustrations vi Contributors vii Preface and Acknowledgements xi Foreword Craig Jefrey xiii Introduction: Worth the Wait Andreas Bandak and Manpreet K. Janeja 1 1 Great Expectations?: Between Boredom and Sincerity in Jewish Ritual ‘Attendance’ Simon Coleman 41 2 Hope and Waiting in Post-Soviet Moscow Jarrett Zigon 65 3 Time and the Other: Waiting and Hope among Irregular Migrants Synnøve Bendixsen and Tomas Hylland Eriksen 87 4 Waiting for God in Ghana: Te Chronotopes of a Prayer Mountain Bruno Reinhardt 113 5 Providence and Publicity in Waiting for a Creationist Teme Park James S. -

Illegal Cultural Commons and the Modern European Cultural Identity a Case Study on Illegal Cultural Commons in the Heart of Europe

UNIVERSITY OF TWENTE Illegal Cultural Commons and the modern European Cultural Identity A case study on illegal cultural Commons in the Heart of Europe Yannik Seyfert (s1205838) SCHOOL OF MANAGMENT AND GOVERNANCE / DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION STUDY PROGRAMME European Public Administration (European Studies) EXAMINATION COMMITTEE First Supervisor: Dr. Ringo Ossewaarde Second Supervisor: Dr. Minna van Gerven-Haanpaa Illegal Cultural Commons in the heart of Europe Yannik Seyfert 1 Content 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Research Question ..................................................................................................................... 5 2. Conceptualization ........................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Concluding Remarks .................................................................................................................. 7 3. Methods ....................................................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Case Selection ............................................................................................................................ 9 3.2 Data Collection ........................................................................................................................ 10 3.3 Operationalization .................................................................................................................. -

Fortress Europe”

– to all recipients of “FORTRESS EUROPE” ... This promotional PDF is hereby offered to the public. File sharing is approved & encouraged by its author, Ryan Bartek. While reviews are appreciated, we know this is a time-consuming request. Therefore, we mainly seek news mentions & web-links that clearly explain where to download “FORTRESS EUROPE (The Big Shiny Prison Vol. II)” for FREE. “FORTRESS EUROPE” is the sequel to “THE BIG SHINY PRISON.” Both books are works of nonfiction travel journalism revolving around the counterculture. While “THE BIG SHINY PRISON (Volume One)” covered the USA underground, it's follow-up details the author's odyssey thropugh the European underground in 2011. “FORTRESS EUROPE” is the third book by Ryan Bartek, preceded by “THE BIG SHINY PRISON” (2009) & his debut anthology “THE SILENT BURNING” (2005). Ryan Bartek is a veteran musician of grindpunk acts SASQUATCH AGNOSTIC & A.K.A. MABUS. He also performs acoustic/antifolk under the alias JACK CASSADY, does live spoken word (as Ryan Bartek) & has toured nationally. Bartek has been published in a host of zines/newspapers, including Metal Maniacs, PIT Magazine, and HAILS & HORNS, among others. Having glimpsed the future & again been cast into the hopeless, futile purgatory that is The United States, the author is seeking citizenship, residency, or legitimate working visa to any country in the European Union. If anyone can assist relocation by legal means, contact Bartek directly (via) [email protected] or [email protected] When in the United States, Ryan Bartek lives & works in Portland, Oregon. Download the author's entire artistic canon 100% FREE here: http://ryanbartek.angelfire.com/blog/ Thanks in Advance, The Anomie PR Team * * * FORTRESS EUROPE is dedicated to Frank Castle, Water Kovacs & Paul Kersey The worst childhood friends a boy could ever have. -

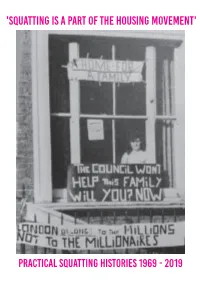

'Squatting Is a Part of the Housing Movement'

'Squatting Is A Part OF The HousinG Movement' PRACTICAL SQUATTING HISTORIES 1969 - 2019 'Squatting Is Part Of The Housing Movement' ‘...I learned how to crack window panes with a hammer muffled in a sock and then to undo the catch inside. Most houses were uninhabit- able, for they had already been dis- embowelled by the Council. The gas and electricity were disconnected, the toilets smashed...Finally we found a house near King’s Cross. It was a disused laundry, rather cramped and with a shopfront window...That night we changed the lock. Next day, we moved in. In the weeks that followed, the other derelict houses came to life as squatting spread. All the way up Caledonian Road corrugated iron was stripped from doors and windows; fresh paint appeared, and cats, flow- erpots, and bicycles; roughly printed posters offered housing advice and free pregnancy testing...’ Sidey Palenyendi and her daughters outside their new squatted home in June Guthrie, a character in the novel Finsbury Park, housed through the ‘Every Move You Make’, actions of Haringey Family Squat- ting Association, 1973 Alison Fell, 1984 Front Cover: 18th January 1969, Maggie O’Shannon & her two children squatted 7 Camelford Rd, Notting Hill. After 6 weeks she received a rent book! Maggie said ‘They might call me a troublemaker. Ok, if they do, I’m a trouble maker by fighting FOR the rights of the people...’ 'Squatting Is Part Of The Housing Movement' ‘Some want to continue living ‘normal lives,’ others to live ‘alternative’ lives, others to use squatting as a base for political action. -

Anarchism in Action -- Page 1

Anarchism in Action -- Page 1 Anarchism in Action: Methods, Tactics, Skills, and Ideas First Edition (revised and expanded) Compiled and Edited by Shawn Ewald Anarchism in Action -- Page 2 Table of Contents Introduction Forms of Decision Making and Organization Direct Democracy Consensus Affinity Groups Collectives Federations and Networks Communication: Getting the Word Out Postering, Tabling, and Propaganda Distribution Tips on Giving Speeches and Presentations Traditional Alternative media Microradio The Internet and Independent Media Mainstream press relations Organizing and Action Types of Organizing Community Organizing Labor Organizing Student Organizing Building Coalitions Types of Actions Protests Strikes and Labor Actions Le Tute Bianche, W.O.M.B.L.E.S., Black Blocs, and Police Confrontation Monkeywrenching Squatting as a Protest Tactic Rooftop Occupations Hunger Strikes Street Parties and Street Theater Billboard Improvement Jail Solidarity Security, Protection, and Self-Defense Security Practices and Security Culture Police Tactics and Your Legal Rights Legal Observers Action Reconnaissance and Scouting Basic First Aid and Street Medics Physical Self-Defense Anarchism in Action -- Page 3 (Table of Contents continued) Anarchist Projects Social Centers, Community Spaces, and Squats Infoshops Microradio Stations Mutual Aid Projects Tenant's Unions Free Schools IWW and IWA Food Not Bombs Homes Not Jails Anti-Racist Action Copwatch Earth First! ACT UP Reclaim The Streets Fundraising and Non-Profit Organizations Fundraising Activities Grant Proposal Writing and Foundation Funding Starting an unincorporated association or non-profit References and Recommended Reading Anarchism in Action -- Page 4 Introduction "Now you ask me how you could help this movement or what you could do, and I have no hesitation in saying, much. -

National Identity at the Margins of Europe: History, Affect and Museums in Slovenia Robert Booth University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-8-2014 National Identity at the Margins of Europe: History, Affect and Museums in Slovenia Robert Booth University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Booth, Robert, "National Identity at the Margins of Europe: History, Affect and Museums in Slovenia" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 407. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/407 Abstract: National Identity at the Margins of Europe: History, Affect and Museums in Slovenia Robert Allen Booth, Ph.D. University of Connecticut 2014 This study examines the historical and idiographic aspects of national identity in Slovenia and brings empirical data to bear on the question of the effect of museums and their identity narratives on citizen museum attendees. Museums have often been portrayed as such sites of identity construction and as important state-making and state-maintaining institutions that educate citizens on the history and heritage of nationhood and nationality. This empirical data is coupled with ethnographic and discourse analytic approaches to demonstrate that the apprehension of identity is predicated on broader historical, socio-political, emotional, moral and economic aspects of society. This dissertation specifically engages four questions: (1) If museums are conduits for societal “memory work”, “place making” and identity building, as is often claimed,