The Intonation of Focused Negation and Affirmation in Spanish in Contact with Catalan1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Third Declension, That Is, Consonant-Stem Nouns; Patterns I

Chapter 7: Third-Declension Nouns Chapter 7 covers the following: third declension, that is, consonant-stem nouns; patterns in the formation of the nominative singular of third declension; and the agreement between third- declension nouns and first/second-declension adjectives. At the end of the lesson, we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There is only one important rule to remember here: the genitive singular ending in third declension is -is . We’ve already encountered first- and second-declension nouns. Now we’ll address the third. A fair question to ask, and one which some of you may be asking, is why is there a third declension at all? Third declension is Latin’s “catch-all” category for nouns. Into it have been put all nouns whose bases end with consonants ─ any consonant! That makes third declension very different from first and second declension. First declension, as you’ll remember, is dominated by a-stem nouns like femina and cura . Second declension is dominated by o- or u-stem nouns like amicus or oculus . Those vowels give those declensions a certain consistency, but the same is not true of third declension where one form, the nominative singular, is affected by the fact that its ending -s runs into the wide variety of consonants found at the ends of the bases of third-declension nouns, and the collision of those consonants causes irregular forms to appear in the nominative singular. That’s the bad news. The good news is that only one case and number is affected by this, the nominative singular. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

AUTHOR a Longitudinal Study of the Language Development Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 247 706 EC 170 061 AUTHOR Mohay, Heather TITLE A Longitudinal Study of the Language Development of Three Deaf Children of Hearing Parents. PUB DATE , Jun 81 NOTE 26p.,.; Paper presented at a Seminar on Early Intervention or Young Hearing-Impaired Children (Mt. Gravatt., Queensland, Australia, June 15-16,-1981). For the proceedings, see EC 170 057. PUB TYPE Reports' = Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS. *Hearing.Impairments; Infants; *Language Acquisition; Longitudinal Studies; *Manual Communication; Sign Language; Young Children (F ABSTRACT A longitudinal study followed the language acquisition'of three deaf infants. Analysis of videotapes recorded in the child's home during informal play was performed in terms of communicative gestures. Results revealed that Ss used a very limited number of hand configurations, locations for signs, and hand and arm, movements. Analysis of the gestures showed that there was a great deal of similarity in the components used by the three Ss, Ss presented consistent patterns in their gestures. Although the single gesture utterance was the most common communicative form, all Ss did combine gestures to form two-gesture utterances. Speech was infrequently used, and all Ss had larger gestural than spoken lexitons at 30 months. It was possible for elements in two gesture utterances and word/gesture combinations to be produced simultaneously. The content of the utterances indicated that they were able to express the same semantic relationships as hearing children at a similar stage of language development. (CL) 9 *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

Measuring the Comprehension of Negation in 2- to 4-Year-Old Children Ann E

Measuring the comprehension of negation in 2- to 4-year-old children Ann E. Nordmeyer Michael C. Frank [email protected] [email protected] Department of Psychology Department of Psychology Stanford University Stanford University Abstract and inferential negation (i.e. negation of inferred beliefs of others). Regardless of taxonomy, negation is used in a variety Negation is one of the most important concepts in human lan- guage, and yet little is known about children’s ability to com- of contexts to express a range of different thoughts. prehend negative sentences. In this experiment, we explore The relationship between different types of negation is un- how children’s comprehension of negative sentences changes between 2- to 4-year-old children, as well as how comprehen- known. One possibility is that distinct categories of negation sion is influenced by how negative sentences are used. Chil- belong to a single cohesive concept. Even pre-linguistically, dren between the ages of 2 and 4 years watched a video in nonexistence, rejection, and denial could all fall under a su- which they heard positive and negative sentences. Negative sentences, such as “look at the boy with no apples”, referred perordinate conceptual category of negation. It is also pos- either to an absence of a characteristic or an alternative char- sible, however, that these types of negation represent fun- acteristic. Older children showed significant improvements in damentally different concepts. For example, the situation in speed and accuracy of looks to target. Children showed more rejection difficulty when the negative sentence referred to nothing, com- which a child expresses a dislike for going outside ( ) pared to when it referred to an alternative. -

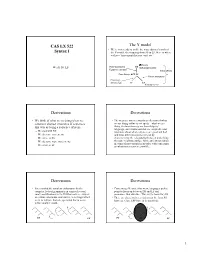

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian Evidential System Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian evidential system Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin This paper provides an account of the Bulgarian admirative construction andits place within the Bulgarian evidential system based on (i) new observations on the morphological, temporal, and evidential properties of the admirative, (ii) a criti- cal reexamination of existing approaches to the Bulgarian evidential system, and (iii) insights from a similar mirative construction in Spanish. I argue in particular that admirative sentences are assertions based on evidence of some sort (reporta- tive, inferential, or direct) which are contrasted against the set of beliefs held by the speaker up to the point of receiving the evidence; the speaker’s past beliefs entail a proposition that clashes with the assertion, triggering belief revision and resulting in a sense of surprise. I suggest an analysis of the admirative in terms of a mirative operator that captures the evidential, temporal, aspectual, and modal properties of the construction in a compositional fashion. The analysis suggests that although mirativity and evidentiality can be seen as separate semantic cate- gories, the Bulgarian admirative represents a cross-linguistically relevant case of a mirative extension of evidential verbal forms. Keywords: mirativity, evidentiality, fake past 1 Introduction The Bulgarian evidential system is an ongoing topic of discussion both withre- spect to its interpretation and its morphological buildup. In this paper, I focus on the currently poorly understood admirative construction. The analysis I present is based on largely unacknowledged observations and data involving the mor- phological structure, the syntactic environment, and the evidential meaning of the admirative. Elena Karagjosova. -

Two-Word Utterances Chomsky's Influence

Two-Word Utterances When does language begin? In the middle 1960s, under the influence of Chomsky’s vision of linguistics, the first child language researchers assumed that language begins when words (or morphemes) are combined. (The reading by Halliday has some illustrative citations concerning this narrow focus on “structure.”) So our story begins with what is colloquially known as the “two-word stage.” The transition to 2-word utterances has been called “perhaps, the single most disputed issue in the study of language development” (Bloom, 1998). A few descriptive points: Typically children start to combine words when they are between 18 and 24 months of age. Around 30 months their utterances become more complex, as they add additional words and also affixes and other grammatical morphemes. These first word-combinations show a number of characteristics. First, they are systematically simpler than adult speech. For instance, function words are generally not used. Notice that the omission of inflections, such as -s, -ing, -ed, shows that the child is being systematic rather than copying. If they were simply imitating what they heard, there is no particular reason why these grammatical elements would be omitted. Conjunctions (and), articles (the, a), and prepositions (with) are omitted too. But is this because they require extra processing, which the child is not yet capable of? Or do they as yet convey nothing to the child—can she find no use for them? Second, as utterances become more complex and inflections are added, we find the famous “over-regularization”—which again shows, of course, that children are systematic, not simply copying what they here. -

Annotating Tense, Mood and Voice for English, French and German

Annotating tense, mood and voice for English, French and German Anita Ramm1;4 Sharid Loaiciga´ 2;3 Annemarie Friedrich4 Alexander Fraser4 1Institut fur¨ Maschinelle Sprachverarbeitung, Universitat¨ Stuttgart 2Departement´ de Linguistique, Universite´ de Geneve` 3Department of Linguistics and Philology, Uppsala University 4Centrum fur¨ Informations- und Sprachverarbeitung, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat¨ Munchen¨ [email protected] [email protected] fanne,[email protected] Abstract features. They may, for instance, be used to clas- sify texts with respect to the epoch or region in We present the first open-source tool for which they have been produced, or for assigning annotating morphosyntactic tense, mood texts to a specific author. Moreover, in cross- and voice for English, French and Ger- lingual research, tense, mood, and voice have been man verbal complexes. The annotation is used to model the translation of tense between based on a set of language-specific rules, different language pairs (Santos, 2004; Loaiciga´ which are applied on dependency trees et al., 2014; Ramm and Fraser, 2016)). Identi- and leverage information about lemmas, fying the morphosyntactic tense is also a neces- morphological properties and POS-tags of sary prerequisite for identifying the semantic tense the verbs. Our tool has an average accu- in synthetic languages such as English, French racy of about 76%. The tense, mood and or German (Reichart and Rappoport, 2010). The voice features are useful both as features extracted tense-mood-voice (TMV) features may in computational modeling and for corpus- also be useful for training models in computational linguistic research. linguistics, e.g., for modeling of temporal relations (Costa and Branco, 2012; UzZaman et al., 2013). -

Oksana's BU Paper

ACQUISITION of GENDER in RUSSIAN * Oksana Tarasenkova University of Connecticut 1 The Background In adult Russian grammar the gender feature of nouns is closely related to their declension class. Their relationship was a controversial question that evoked two opposing views regarding the way gender is represented in adult Russian grammar. The representatives of one view argue for gender to be derived from the noun declension class (Declension-to Gender account, Corbett 1982), while proponents of the opposite account argue for the reversed pattern, where the inflectional morphology can be predicted from the information on the noun gender along with a phonological cue (Gender-to-Declension account, Vinogradov 1960, Thelin 1975, Crockett 1976 among others). My goal is to focus on children’s acquisition of gender in Russian in order to compare these two major divisions of research. They provide different morphological analyses of gender forms in Russian; therefore this debate makes different predictions about the acquisition of gender by children. I tested these opposing predictions using children’s data gathered from an experiment to identify what exactly children rely on when assigning gender to nouns. The experiment results support the Declension-to-Gender view and provide evidence that children are significantly more successful at assigning gender to the novel nouns relying on the nominal declension paradigm rather than on the adjectival agreement. The way gender is represented in adults’ competence grammar might not necessarily be the correct model of children’s acquisition of gender. The child has to learn the gender of a significant number of nouns and extract the declensional paradigms first in order to then be able to learn and apply these redundancy rules for novel nouns.