Sunderland Retail Needs Assessment 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heart of Sunderland City Centre

A market defining office building in the heart of Sunderland City Centre Vaux, Sunderland 2,500 sq.ft up www.the-beam.co.uk to 59,427 sq.ft by the sea a changing city Sunderland: Sunderland is a city undergoing transformation, with over £1.5 billion of investment planned ahead of 2024 and a thriving cultural offer, in line with a clear vision for the future. The Beam is only just the start. Exciting plans for city centre redevelopment build on the success of companies such as Nissan and a world-class advanced manufacturing sector; the city’s highly regarded business, fi nancial and professional services sector at Doxford International and Hylton Riverside; and our established software and digital sector. Our proud industrial heritage is creating the conditions for 2 - 3 a thriving modern economy. development A ground breaking Vaux The Beam is the first building to be developed at VAUX, a ground breaking mixed use development at the iconic home of Sunderland’s former city centre brewery. Buildings at Vaux are being built with wellbeing at their heart, with stunning views and spaces for people to live well, work well and feel good. The Vaux Masterplan sets out an ambitious and imaginative reinvention of this former brewery site, delivering high-quality offi ce accommodation together with complementary residential, retail, food and drink, hotel and leisure uses, all linked to the city centre via the new Keel Square. > Offices 45,523 sqm > Retail, restaurant & leisure 3,716 sqm > Residential 250 homes > Exhibition/office space 3,995 sqm > Hotel 1,858 sqm > Secure car parking > Superb transport links within short walking distance 4 - 5 by the sea a changing city Sunderland: ‘C’ Sculpture, Roker Beach With a location that lends itself to all the advantages of city life, with a hassle- free commute and the riverside and coast on the doorstep, Vaux is a place for business to flourish and for people to thrive. -

Cheeky Chattering in Sunderland

Cheeky Chattering in Sunderland We travelled into Sunderland so that we can show you how great it is here. The Bridges Shopping Centre The Bridges is in the centre of Sunderland. You can eat in cafes and restaurants and do some shopping. Here are some of our favourite shops Don’t tell Mr Keay we popped into Krispy Kreme! The Head teacher thinks we ‘re working! Mmm, this chocolate doughnut Sunderland Winter Gardens and Museum Sunderland museum first opened almost 150 years ago The Winter Gardens is a museum, we know that because the museum is old. Finding out about the museum Jenny told us all about the museum This is Wallace the lion, he is nearly 150 years old. When the museum first opened children who were blind could visit the museum to feel his fur. Coal mining in Sunderland I would not like to work in the mine Life as a coal miner Working in the mines was dangerous. This family has had to leave their home because their dad was killed in the mine. Inside the Winter Gardens William Pye made this ‘Water Sculpture’ Penshaw Monument Look at the view Penshaw Monument from the top was built in 1844 On Easter Splat! Monday In 1926 a 15 year old boy called Temperley Arthur Scott fell from the top of Penshaw We climbed to Monument and the top of the died. monument It was a cold Winter’s day when Herrington Country Park we visited the park. There are lots of lovely walks to do in the park A skate park for scooters and bikes Stadium of Light Sunderland’s football ground Stadium of Light Samson and Delilah are Sunderland’s mascots River Wear The Beaches in Sunderland There are two beaches in Sunderland called Roker and Seaburn Look at the fun you can have at Seaburn This is what we think about My favourite Bridges Sunderland shop is Game because I support you buy games toys and Sunderland game consoles football club and Ryan, year 7 I like to do football trick. -

River Wear Commissioners Building & 11 John Street

Superb Redevelopment Opportunity RIVER WEAR COMMISSIONERS BUILDING & 11 JOHN STREET SUNDERLAND SR11NW UNIQUE REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY The building was originally opened in 1907 as the Head Office of the River Wear Commissioners and is widely viewed as one of the most important We are delighted to offer this unique redevelopment historical and cultural buildings in Sunderland. opportunity of one of Sunderland’s most important buildings, Located on St Thomas Street, it is a superb Grade II listed period building in a high profile position in the the River Wear Commissioners Building and 11 John Street. city centre, suitable for a variety of uses. UNIQUE REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY “One of the most important historical and cultural buildings in Sunderland.” LOCATION Sunderland is the North East’s largest city, with a population of approximately 275,506 (2011 Census) and a catchment population Sunderland is one of the North East’s most important commercial of 420,268 (2011 Census). The City enjoys excellent transport centres, situated approximately 12 miles south east of Newcastle communications linking to the main east coast upon Tyne and 13 miles north east of Durham. arterial routes of the A19 and the A1(M). Sunniside Gardens Winter Gardens Central Station Park Lane Interchange Travelodge Ten-Pin Bowling University of Casino Frankie & Benny’s Sunderland Halls of Residence Empire Nando’s Multiplex Debenhams Cinema THE BRIDGES Marks & SHOPPING CENTRE Crowtree TK Maxx Spencer Leisure Centre University Argos St Mary’s Car Park University of Sunderland City Wearmouth Bridge Campus Keel Square Sunderland Empire Theatre Travelodge St Peter’s Premier Inn Sunderland’s mainline railway station runs The property is very centrally located on the Sunderland Regeneration services to Durham and Newcastle with a corner of St Thomas Street and John Street fastest journey time to London Kings Cross of in the heart of the city centre and opposite Sunderland is a city benefitting from an extensive regeneration program, 3 hours 20 minutes. -

Language Variation And. Identity

LanguageVariation and.Identity in Sunderland (Volume 1) LourdesBurbano-Elizondo Doctor of Philosophy National Centre for English Cultural Tradition (School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics) The University of Sheffield September2008 Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to expressmy gratitude to the National Centre for English Cultural Tradition for financially supporting this PhD and thus making possiblethe conductof this project. I would also like to thank Joan Beal (NATCECT, School of English Literature, Languageand Linguistics) and Emma Moore (School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics) for supervisingmy study and providing me with invaluable advice and supportthroughout the whole process.Tbanks also to the Departmentof English at EdgeHill University for their supportand facilitation. Thanks must go to the NECTE team for granting me accessto recordings and transcriptions when they were still in the process of completing the corpus. I am indebted to Carmen Llamas, Dom Watt, Paul Foulkes and Warren Maguire who at different stagesin my dataanalysis offered their guidanceand help. I am very grateful to Elizabeth Wiredu (Leaming Support Adviser from the Learning ServicesDepartment of Edge Hill University) for her assistancewith some of the statisticsconducted in the dataanalysis. My thanks are due to Lorenzo and Robin for providing me accommodationevery time I went up to Sunderlandto do my fieldwork. I must also gratefully acknowledgeall the Sunderlandpeople who volunteeredto participatein my study. This study would not havebeen possible without their help. Special thanks go to Anna, Natalia, Heike, Alice, John, Esther and Damien for innumerablefavours, support and encouragement.I must also thank Damien for his patienceand understanding,and his invaluablehelp proof-readingthis work. -

Brochure 2020

e more Guaranteed progression to one of the UK’s leading modern universities 2020-2021 Achie Achie ONCAMPUS is proud to work in partnership with Contents the University of Sunderland to offer high-quality university preparation programmes for international students on the University campus. About University of Sunderland Highlights 4 The University of Sunderland is an innovative, forward-thinking Faculty highlights 6 university with high standards of teaching, research and support, which sits at the heart of one of the UK’s most up-and-coming cities. Progression degrees It has strong links with industry and business, and works closely with Undergraduate degrees 8 some of the world’s leading companies. Master’s degrees 9 The University has invested more than £130 million in its two About ONCAMPUS campuses – the Sir Tom Cowie Campus by the riverside, and the City How ONCAMPUS works 10 &DPSXVLQWKHFLW\FHQWUHâVRVWXGHQWVFDQHQMR\İUVWFODVVIDFLOLWLHV Our Programmes: and high-quality courses that are perfectly placed to ensure a life- changing student experience. Undergraduate Foundation Programme (UFP) 12 International Year One (IY1) 14 Master’s Foundation Programme (MFP) 16 About Student Life Accommodation 18 Applying Next steps 20 Application form 21 Download our Coursefinder app designed to help you discover your ideal degree at the University of Sunderland 02 03 Highlights About the University of Sunderland Sunderland Highlights Leeds Hull 4 hours Liverpool to London by train Birmingham as well as great train links to other UK cities such as Leeds, Manchester, S Birmingham, Leicester and more... ta s d le iu i Oxford m m London .2 of Light 1 Population of Sunderland: m Cowie Ca To m 170,000+ ir pu State-of-the-art S s 1 .4 Just over m £8.5 million i l e 3 miles s Sciences Complex to Sunderland’s allows students access to International Airshow – the biggest free annual airshow Centre 1.4 m in Europe, which includes the ss m 1.2 iles la i tre outstanding facilities famous Red Arrows. -

Chester Gate Modern 2, 3 and 4 Bedroom Homes We Are Committed to the Consumer Code for Home Builders

5 Star Excellence as standard Chester Gate Modern 2, 3 and 4 bedroom homes We are committed to the Consumer Code for Home Builders. All images are for illustration purposes only. For more information please visit www.consumercode.co.uk 5 Star Excellence as standard Chester Gate provides you with the best of both worlds. Our homes are ideally situated to act as a gateway to commute to or explore the attractions of the city and are also within easy reach of the beautiful beaches along the North East coastline. With our new homes so close to the city centre Seaburn, both featuring popular coastal cafés you really are spoilt for choice. Within a short and restaurants to indulge. The attraction of 10 minute drive you can reach the The Bridges the coast is not just felt in the summer, with Shopping Centre which is host to an abundance Sunderland Illuminations lighting up the seafront of big-name brands making it perfect for a spot throughout the winter evenings allowing you to of retail therapy. enjoy enchanted coastal walks. There is also the option to take in a show at The You can also make the most of the outdoors at Sunderland Empire Theatre with musicals and the New Herrington Recreational Park, just a 10 tribute bands, or enjoy the drama on the football minute drive from our new homes, which pitch at the Stadium of Light. Situated in the heart includes a play area, café and sports grounds of the city, Mowbray Park is a great place to spend as well as providing miles of stunning country the day featuring Sunderland Museum which walk and cycle trails. -

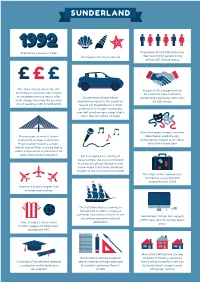

Fact-Card-Sheets.Pdf

Granted city status in 1992 Population of 275,000 with more The largest UK city by the sea than two million people living within a 30-minute radius The ‘third richest city in the UK’, A total of 80 companies from according to scientists who looked 20 countries have located in at the assets the city has to offer Sunderland’s Nissan Motor Sunderland employing more than vs the things that play the greatest Manufacturing UK is the country’s 25,000 people role in leading a rich & fulfilled life largest car manufacturer & most productive in Europe, producing over half a million cars a year (that’s more than the whole of Italy!) With the largest theatre between Recent past, current & future Manchester & Edinburgh, investment is close to £1billion. Sunderland is known as the West Regeneration includes a multi- End of the North East million pound Wear crossing that is under construction & planned to be taller than London’s Big Ben Set to compete for UK City of Culture 2021, the city is immersed in a host of cultural initiatives with a new music & arts hub scheduled to open in the city centre mid-2016 The city’s visitor numbers are increasing, up by 200,000 compared with 2013 Home to Europe’s largest free international airshow The Tall Ships Race is coming to Sunderland in 2018, bringing a potential two million visitors to the Sunderland College has enjoyed city and an economic value of a 99% pass rate for the last seven £50million One of only 11 cities with a years Premier League football team, Sunderland AFC More than £600million is being Sunderland’s -

12306 Beam Brochure Online.Indd

A market defining office building in the heart of Sunderland City Centre Vaux, Sunderland 2,500 sq.ft up www.the-beam.co.uk to 59,427 sq.ft by the sea a changing city Sunderland: Sunderland is a city undergoing transformation, with over £1.5 billion of investment planned ahead of 2024 and a thriving cultural offer, in line with a clear vision for the future. THE BEAM is only just the start. Exciting plans for city centre redevelopment build on the success of companies such as Nissan and a world-class advanced manufacturing sector; the city’s highly regarded business, fi nancial and professional services sector at Doxford International and Hylton Riverside; and our established software and digital sector. Our proud industrial heritage is creating the conditions for 2 - 3 a thriving modern economy. development A ground breaking Vaux THE BEAM is the first building to be developed at VAUX, a ground breaking mixed use development at the iconic home of Sunderland’s former city centre brewery. Buildings at Vaux are being built with wellbeing at their heart, with stunning views and spaces for people to live well, work well and feel good. The Vaux Masterplan sets out an ambitious and imaginative reinvention of this former brewery site, delivering high-quality offi ce accommodation together with complementary residential, retail, food and drink, hotel and leisure uses, all linked to the city centre via the new Keel Square. > Offices 45,523 sqm > Retail, restaurant & leisure 3,716 sqm > Residential 250 homes > Exhibition/office space 3,995 sqm > Hotel 1,858 sqm > Secure car parking > Superb transport links within short walking distance 4 - 5 by the sea a changing city Sunderland: ‘C’ Sculpture, Roker Beach With a location that lends itself to all the advantages of city life, with a hassle- free commute and the riverside and coast on the doorstep, Vaux is a place for business to flourish and for people to thrive. -

Arndale House, 56-62 High Street West Sunderland Sr1 3Bu

ARNDALE HOUSE, 56-62 HIGH STREET WEST SUNDERLAND SR1 3BU freehold, high yielding, retail investment opportunity ARNDALE HOUSE, 56-62 HIGH STREET WEST SUNDERLAND SR1 3BU Investment Summary • A prime retail investment, on High Street West directly opposite Primark which acts as an entrance into The Bridges Shopping Centre. • An established retailing pitch where national retailers include Primark, Argos, Mothercare, Marks & Spencer, BHS, Boots Opticians, McDonalds, Ann Summers and Brighthouse. • Well secured to Shoe Zone Retail Limited and Toni & Guy (South East) Limited as well as a host of independent retailers. • Average Weighted Unexpired Lease Term (AWULT) in excess of 4 years. • Freehold. • Total net rent of £213,791 pax. Location Demographics & Economy Sunderland is one of the North East’s most important commercial The city has a total population within its primary retail catchment • Offers in excess of £2,000,000 (Subject to Contract & of 376,000 and an estimated shopping population of 191,000. It exclusive of VAT) which reflects an attractiveNet Initial Yield centres, located approximately 12 miles (19 km) south east of was announced that Sunderland leads the north east region for of 10% assuming purchasers costs of 6.28%. Newcastle and 25 miles (40 km) north of Middlesbrough. the biggest increase in private sector employment from 2010 to Road communications are excellent as Sunderland is linked to the 2012 (ONS). main East-Coast arterial routes of the A19, 2 miles (3 km) to the west and the A1 (M) at junctions 65 and 62, 7 miles (11 km) to the Nissan Motor Manufacturing UK factory opened in Sunderland in north and 10 miles (16 km) to the south respectively. -

Your City. Your Business. Your BID

UNDERLAND Your City. Your Business. Your BID. Sunderland BID renewal plan for 2019 – 2024 “I think the BID has been great for the city. It’s CONTENTS brought businesses together 04 FROM THEN TO NOW and actually got people 05 OUR VISION 06 YOUR VIEWS working together for the 07 CHALLENGES WE FACE TOGETHER good of the city.” 09 WHAT’S NEXT? 10 CITY PRIDE David Fox, Manager, 14 CITY PROMOTION Tequila, Tequila 18 CITY VOICE 22 DON’T JUST TAKE OUR WORD FOR IT 24 SUNDERLAND BID AREA 25 BID LEVY 26 WHY SUNDERLAND NEEDS A BID 29 THIS IS WHAT YOU WILL LOSE 30 WHY VOTE YES 32 THE RULES 02 03 FROM THEN TO NOW…. Sunderland’s Business Improvement District (BID) is entering the final phase of its first, five-year term. OUR VI ION Since 2014, the BID has invested more than £3m in the city centre. During our first term, key projects have included: ▪ Substantial Christmas programme including: the ice rink, entertainment, street food and drink VISION: ▪ 5 Restaurant Weeks ▪ 2 Sports Fanzones A VIBRANT CITY ▪ 16 editions of Vibe Magazine ▪ 6 Clean Sweep projects CENTRE, CREATING ▪ And so much more OPPORTUNITIES For a recap of what has been achieved since 2014, FOR EVERYONE. please read our ‘Story So Far’ pull out document. The past five years have been very exciting It has been an exciting and successful start to what but they have also been a learning curve. will hopefully be a much longer journey. The second stage of that journey starts here. Using Out of experience comes strength and we the knowledge, insight and skill that has been gained have listened to what our Levy payers have over the past five years has helped us create a had to say and that has allowed us to create relevant and achievable plan for the future. -

The Largest UK City by the Sea Sunderland's Nissan Motor

Granted city status in 1992 Population of over 275,000 with The largest UK city by the sea more than two million people living within a 30-minute radius The ‘third richest city in the UK’, A total of 80 companies from according to scientists who looked 20 countries have located in at the assets the city has to offer Sunderland’s Nissan Motor Sunderland employing more than vs the things that play the greatest Manufacturing UK is the country’s 25,000 people role in leading a rich & fulfilled life largest car manufacturer & most productive in Europe, producing over half a million cars a year (that’s more than the whole of Italy!) With the largest theatre between Recent past, current & future Manchester & Edinburgh, investment is close to £1billion. Sunderland is known as the West Regeneration includes a multi- End of the North East million pound Wear crossing that is under construction & planned to be taller than London’s Big Ben Set to compete for UK City of Culture 2021, the city is immersed in a host of cultural initiatives with a new music & arts hub scheduled to open in the city centre mid-2016 The city’s visitor numbers are increasing, up by 200,000 compared with 2013 Home to Europe’s largest free international airshow The Tall Ships Races is coming to Sunderland in 2018, bringing a potential two million visitors to the Sunderland College has enjoyed city and an economic value of a 99% pass rate for the last seven £50million One of only 11 cities with a years Premier League football team, Sunderland AFC More than £600million is being -

You Are Advised to Telephone the Pharmacy Prior to Attending. If You Require Advice out of Hours, Please Contact: 111

Sunderland - Pharmacy Opening Times Christmas and New Year 2015/16 Christmas Eve Christmas Day Boxing Day New Year's Eve New Year's Day Saturday 26 Pharmacy Address Telephone Thursday 24 Friday 25 Monday 28 Thursday 31 Friday 1 December 2015 December 2015 December 2015 December 2015 December 2015 January 2016 Amcare Ltd 39b Pallion Way, Pallion 0191 5108898 08:30 - 17:30 Closed Closed Closed 08:30 - 17:30 Closed Trading Estate, Sunderland, SR4 6SN Asda Pharmacy Asda Superstore, 0191 5689110 08:00 - 19:00 Closed 09:00 - 18:00 11:00 - 13:00, 08:00 - 19:00 11:00 - 13:00, Leechmere Road 14:00 - 16:00 14:00 - 16:00 Industrial Estate, Grangetown, Sunderland, SR2 9TT Asda Stores Ltd Washington Centre, 0191 4972410 07:00 - 23:00 Closed 07:00 - 22:00 11:00 -13:00, 07:00 - 23:00 11:00 - 13:00, Washington, NE38 7NF 14:00 - 16:00 14:00 - 16:00 Ashchem 5 Sea Road, Fulwell, 0191 5489617 09:00 - 18:00 Closed 09:00 - 17:00 Closed 09:00 - 18:00 Closed Chemists Sunderland, SR6 9BP Avenue 53 Lower Dundas 0191 5673037 07:00 - 22:00 16:00 - 18:00 07:00 - 22:00 Closed 07:00 - 22:00 Closed Pharmacy Street, Mokwearmouth, Sunderland, Tyne & Wear, SR6 0BD Avenue 50 Roker Avenue, 0191 5673088 09:00 - 13:00, Closed Closed Closed 09:00 - 13:00, Closed Pharmacy Sunderland, SR6 0HT 14:00 - 18:00 14:00 - 18:00 Avenue 81 Dundas Street, 0191 5672812 09:00 - 13:00, Closed Closed Closed 09:00 - 13:00, Closed Pharmacy Sunderland, SR6 0AY 13:30 - 17:30 13:30 - 17:30 B Braun Medical Holmlands Buildings, 0800 163007 08:30 - 16:30 Closed Closed Closed 08:30 - 16:30 Closed Limited Tunstall Road, Sunderland, SR2 7RR You are advised to telephone the pharmacy prior to attending.