Issue 22___Article 15.Pdf (1.577Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Efforts to Establish a Labor Party I!7 America

Efforts to establish a labor party in America Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors O'Brien, Dorothy Margaret, 1917- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 15:33:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553636 EFFORTS TO ESTABLISH A LABOR PARTY I!7 AMERICA by Dorothy SU 0s Brlen A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Economics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate College University of Arizona 1943 Approved 3T-:- ' t .A\% . :.y- wissife mk- j" •:-i .»,- , g r ■ •: : # ■ s &???/ S 9^ 3 PREFACE The labor movement In America has followed two courses, one, economic unionism, the other, political activity* Union ism preceded labor parties by a few years, but developed dif ferently from political parties* Unionism became crystallized in the American Federation of Labor, the Railway Brotherhoods and the Congress of Industrial Organization* The membership of these unions has fluctuated with the changes in economic conditions, but in the long run they have grown and increased their strength* Political parties have only arisen when there was drastic need for a change* Labor would rally around lead ers, regardless of their party aflliations, -

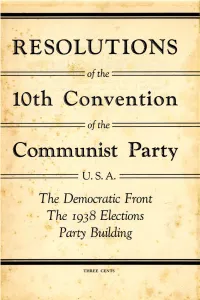

Resolutions of the 10Th Convention of the Communist Party, U.S.A

RESOLU.TIONS ============'==' ofthe ============== " , 10th C'onvention ==============.=. ofthe ============== Communist Party ====:::::::::===:::::::= tJ. S. A. ============= ": The Democra.tic Front ~ ~ T~e 1938 Elections Party Building THREE CENTS NOTE These Resolutions were unanimously adopted by the Tenth National Convention of the Communist Party, U.S.A., held in New York, May 27 to 31, 1938, after two months of pre-convention discussion by the'enti're: membership in every local branch and unit. They should be read in connection with the report to the Convention by Earl Browder, General Secretary, in behalf of the National Committee, published under the title The Democratic Front: For Jobs, Security, Democracy and Peace. (Workers Library Publishers. 96 pages; price 10 ,cents.) PUBLISHED BY WORKERS LIBRARY PUBLISHERS, INC. P. O. BOX 1-48, STATION D, NEW YORK CITY JULY,, 1938 PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. THE OFFENSIVE OF REACTION AND THE BUILDING OF THE DEMOCRATIC FRONT I A S PART of the world offensive of fascism, which is l""\..already extending to the Americas, the most reactionary section of finance capital in the United States is utilizing the developing economic crisis, which it has itself hastened and aggravated, as the basis for a major attack against the rising labor and democratic movements. This reactionary section of American finance capital con tinues on a "sit-down strike" to defeat Roosevelt's progressive measures and for the purpose of forcing America onto the path of reaction, the path toward fascism and war. It exploi~s the slogans of isolation to manipulate the peace sentiments of the masses, who are still unclear on how to maintain peace. -

Finding Aid Prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISION THE RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTION Finding aid prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C. - Library of Congress - 1995 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK ANtI SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISIONS RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTIONS The Radical Pamphlet Collection was acquired by the Library of Congress through purchase and exchange between 1977—81. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 25 Number of items: Approx: 3465 Scope and Contents Note The Radical Pamphlet Collection spans the years 1870-1980 but is especially rich in the 1930-49 period. The collection includes pamphlets, newspapers, periodicals, broadsides, posters, cartoons, sheet music, and prints relating primarily to American communism, socialism, and anarchism. The largest part deals with the operations of the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA), its members, and various “front” organizations. Pamphlets chronicle the early development of the Party; the factional disputes of the 1920s between the Fosterites and the Lovestoneites; the Stalinization of the Party; the Popular Front; the united front against fascism; and the government investigation of the Communist Party in the post-World War Two period. Many of the pamphlets relate to the unsuccessful presidential campaigns of CP leaders Earl Browder and William Z. Foster. Earl Browder, party leader be—tween 1929—46, ran for President in 1936, 1940 and 1944; William Z. Foster, party leader between 1923—29, ran for President in 1928 and 1932. Pamphlets written by Browder and Foster in the l930s exemplify the Party’s desire to recruit the unemployed during the Great Depression by emphasizing social welfare programs and an isolationist foreign policy. -

The Withering Away of the American Labor Party

THE WITHERING AWAY OF THE AMERICAN LABOR PARTY BY ALAN WOLFE Assistant Professor of Political Science Douglass College, Rutgers University EW YORK State's American Labor Party (1936-56) existed in a variety of forms: pro-Democratic electoral vehicle (1936), independent third party (1937-44), one of two "third-parties" in the state (1944-47), state branch of the national Progressive Party (1948-52), and ideological interest group with strong pro-communist leanings (1953-56). Most scholarly studies of the party, such as those of Bone, Sarasohn, and Moscow,1 which end in either 1946 or 1948, have treated only the first three forms. Because of this, the last eight years of the American Labor Party remain unexamined. Text-book treatments skip over the 1948-56 period with passing references to communist domination or infiltration.2 This unfortunate lacuna deserves to be filled, and the recent acquisition by the Rutgers University Library of the party's papers for this period provides the wherewithal to do so.3 1948 was a key year in the history of the American Labor Party because of the candidacy of Henry A. Wallace for President. No sooner had the year begun than on January 7, at a meeting of the state executive committee of the party, the ALP split over the ques- tion of endorsing Roosevelt's former Vice-President. Anticipating a strong pro-Wallace move, the state chairman, state treasurer, and 1 Hugh A. Bone, "Political Parties in New York State," American Political Science Review, 40 (April 1946), 272-82 ; Stephen B. Sarasohn, The Struggle for Control of the American Labor Party, 1936-48 (Unpublished Master's Essay, Columbia University, 1948) ; and Warren Moscow, Politics in the Emfire State (New York, 1948), Chapter 7. -

294 I T DIDN't HAPPEN HERE Socialist Movements, Left Came to Mean Greater Emphasis on Communitarianism and Equality, on the State As an Instrument of Reform

294 I T DIDN'T HAPPEN HERE socialist movements, left came to mean greater emphasis on communitarianism and equality, on the state as an instrument of reform. The right, linked to defensive establishments, has, particularly since World War II, been identified with opposition to government intervention. The rise of Green parties in Western Europe is merely one indication that the contest between these two orientations has not ended. The United States, without a viable Green party, appears as different from Western Europe as ever. NOTES 1. An Exceptional Nation 1. Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, vol. 2 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948), pp. 36-37; Engels to Weydemeyer, August 7, 1851, in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Letters to Americans, 1848-1895 (New York: International Publishers, 1953), pp. 25-26. For evidence of the continued validity and applicabili- ty of the concept see Seymour Martin Lipset, American Exceptionalism: A Double- Edged Sword (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996), esp., pp. 32-35, 77-109. On American cultural exceptionalism, see Deborah L. Madsen, American Exceptionalism (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998). 2. See Seymour Martin Lipset, "Why No Socialism in the United States?" in S. Bailer and S. Sluzar, eds., Sources of Contemporary Radicalism, I (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1977), pp. 64-66, 105-108. See also Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1989), pp. 247-248, 256-266; Draper, American Communism and Soviet Russia: The Formative Period (New York: Viking Press, 1960), pp. 269-272, 284. 3. Richard Flacks, Making History: The Radical Tradition in American Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), pp. -

Clifford T. Mcavoy, Active Fighter for Socialism

Hiss’ Own Story A Book Review (See Page 3) t h e MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Vol. XXI - No. 33 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, AUGUST 19, 1957 PRICE 10c Clifford T. McAvoy, Active Fighter for Congress Prepares to Send Socialism; Dies Harry Ring Civil Rights Bill to Its Grave The fight for a Socialist America suffered a grievous - — --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------f y --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- loss with the death of Clifford T. McAvoy on Aug. 9. A former leader of the American Labor Party in New York, McAvoy had played an important S --------------------------------------------------- role in current efforts to achieve Many Cases Revealed a regroupmcnt of revolutionary Strike Flares in Poland socialist forces. He died of nephritis at the age of. 52 _n Cape Cod1 Hospital in Mas Tr Of Political Horse-Trades sachusetts. He had planned to spend a summer vacation there Use Troops and also to play as violinist in the Provincetown Symphony. He With Dixiecrat Senators is survived by his wife and stead To Smash By Fred Hart fast co-worker, Muriel, and by a son and daughter. AUG. 16 — The civil rights -

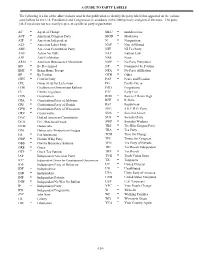

A Guide to Party Labels -150

A GUIDE TO PARTY LABELS The following is a list of the abbreviations used in this publication to identify the party labels that appeared on the various state ballots for the U.S. Presidential and Congressional candidates in the 2008 primary and general elections. The party label listed may not necessarily represent a political party organization. AC = Agent of Change MLU = marklovett.us ACP = American Congress Party MOD = Moderates AIP = American Independent N = Nonpartisan ALP = American Labor Party NAF = Non-Affiliated AMC = American Constitution Party NJT = NJ Tea Party ANT = Action No Talk NLP = Natural Law APP = Anti-Prohibition NNE = None ARM = American Renaissance Movement NOP = No Party Preference BD = Be Determined NP = Nominated by Petition BHT = Bring Home Troops NPA = No Party Affiliation BP = By Petition OTH = Other CEN = Centrist Party PAF = Peace and Freedom CFL = Connecticut for Lieberman PG = Pacific Green CGR = Coalition on Government Reform PRO = Progressive CL = Citizen Legislator PTF = Party Free CON = Constitution RDH = Rent is 2 Damn High CPA = Constitution Party of Alabama REF = Reform CPF = Constitution Party of Florida REP = Republican CPW = Constitution Party of Wisconsin SHE = S.H.E.R.O. Party CRV = Conservative SOA = Socialist Action DAC = Defend American Constitution SUS = Socialist Party DCG = D.C. Statehood Green SWP = Socialist Workers DEM = Democratic TBE = The Blue Enigma Party DNL = Democratic-Nonpartisan League TEA = Tea Party FA = For Americans TCH = Time for Change FWP = Florida Whig Party TFC = Towne for Congress GBS = Gravity Buoyancy Solution TPN = Tea Party of Nevada GRE = Green TRI = Tax Revolt Independent GTP = Green Tea Patriots TRP = Tax Revolt IAP = Independent American Party TVH = Truth Vision Hope ICC = Independent Citizen for Constitutional Government TX = Taxpayers IDE = Independent Party of Delaware UC = United Citizens IDP = Independence UN = Unaffiliated IND = Independent UPA = Unity Party of America INP = Independent Patriots USM = United States Marijuana INW = Independent No War No Bailout UST = U.S. -

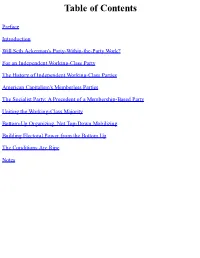

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Preface Introduction Will Seth Ackerman's Party-Within-the-Party Work? For an Independent Working-Class Party The History of Independent Working-Class Parties American Capitalism's Memberless Parties The Socialist Party: A Precedent of a Membership-Based Party Uniting the Working-Class Majority Bottom-Up Organizing, Not Top-Down Mobilizing Building Electoral Power from the Bottom Up The Conditions Are Ripe Notes THE CASE FOR AN INDEPENDENT LEFT PARTY FROM THE BOTTOM UP HOWIE HAWKINS © 2020 Howie Hawkins Originally published in slightly different form in International Socialist Review no. 107 (Winter 2017– 2018), ISReview.org/issue/107/case-independent-left-party, and reprinted in Black Agenda Report, May 10, 2018, www.blackagendareport.com/case-independent-left-party-bottom. This edition published in 2020 and distributed by Howie Hawkins 2020. Some rights reserved. The copyright holder grants the freedom to copy or redistribute this work for noncommercial use in any format with attribution to the author under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0. Consider supporting our work with a donation at www.howiehawkins.us. Cover design by Jamie Kerry, Belle Étoile Studios. Cover photo © Paul Sableman, CC BY 2.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0. In loving memory of Bruce A. Dixon (1950–2019). Rest in power. PREFACE This article was written with two audiences in mind. The first are the supporters of the Green Party of the United States. I hope to persuade them to (1) transform the Green Party structure into a dues- paying, mass-membership party and (2) to prioritize local organizing and elections to build its popular base and political power from the bottom up. -

Roosevelt and the Protest of the 1930S Seymour Martin Lipset

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1984 Roosevelt and the Protest of the 1930s Seymour Martin Lipset Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lipset, Seymour Martin, "Roosevelt and the Protest of the 1930s" (1984). Minnesota Law Review. 2317. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2317 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Roosevelt and the Protest of the 1930s* Seymour Martin Lipset** INTRODUCTION The Great Depression sparked mass discontent and polit- ical crisis throughout the Western world. The economic break- down was most severe in the United States and Germany, yet the political outcome differed markedly in the two countries. In Germany the government collapsed, ushering the Nazis into power. In the United States, on the other hand, no sustained upheaval occurred and political change resulting from the eco- nomic crisis was apparently limited to the Democrats replacing the Republicans as the dominant party.' Why was the United States government able to survive intact the worst depression in modern times? Much of the answer lies in the social forces that have his- torically inhibited class conscious politics in the United States. Factors such as the unique character of the American class structure (the result of the absence of feudal hierarchical so- cial relations in its past), the great wealth of the country, the * This Article is part of a larger work dealing with the reasons why the United States is the only industrialized democratic country without a significant socialist or labor party. -

Labor and Politics in the 1930'S

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Plan B Papers Student Theses & Publications 1-1-1967 Labor and Politics in the 1930's Charles E. Gillespie Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b Recommended Citation Gillespie, Charles E., "Labor and Politics in the 1930's" (1967). Plan B Papers. 618. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b/618 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Plan B Papers by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LABOR AND POLITICS IN THE 1930's (TITLE) BY Charles E. Gillespie PLAN B PAPER SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EDUCATION AND PREPARED IN COURSE HISTORY 563 (Seminar on the 1930's) IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY, CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1967 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS PLAN B PAPER BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE DEGREE, M.S. IN ED. CL .J / lf I r,7 (c" 1 U r\ DAiE -- INTRODUCTION Today, American labor is recognized as a part of the greatest productive machine the world has ever known. The present status of labor, however, developed only within the past thirty years. In this general survey of labor in hte 1930's the many barriers and obstacles experienced in the growth of organized labor will be discussed. In the history of the United States periods of great change have emerged. New conditions and attitudes take root and break long established precedents. -

Political Incorporation and Political Extrusion: Party Politics and Social Forces in Postwar New York

_________ C HAP T E R 6 ______---'__ Political Incorporation and Political Extrusion: Party Politics and Social Forces in Postwar New York THE MOVEMENT of new social forces into the political system is one of the central themes in the study of American political development on both the national and local levels. For example, Samuel P. Huntington has character ized the realignment of 1800 as marking "the ascendancy of the agrarian Republicans over the mercantile Federalists, 1860 the ascendancy of the industrializing North over the plantation South, and 1932 the ascendancy of the urban working class over the previously dominant business groups."! And the process of ethnic succession-the coming to power of Irish and German immigrants, followed by the Italians and Jews, and then by blacks and Hispanics- is a major focus of most analyses of the development of American urban politics. Most accounts of political incorporation, however, are based on an analy sis of only one face of a two-sided process. The process through which new social forces gain a secure position in American politics is simultaneously a process of political exclusion. This process involves not simply a conflict between the new group and established forces over whether or not the new comers will gain representation, but also a struggle over precisely who will assume leadership of the previously excluded group. Established political forces are not indifferent to the outcome of these leadership struggles, and the defeat of potential leaders who are regarded as unacceptable by estab lished forces is the price that emergent groups must pay to gain access to po\,ver. -

Eugene Victor Debs (1855-1926)

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition Pro uesf Start here. This volume is a finding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research, the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world's knowledge-from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. Eisenhower Parkw~y • P.O Box 1346 • Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 • USA •Tel: 734.461.4700 • Toll-free 800-521-0600 • www.proquest.com The Papers of Eugene V. Debs 1834-1945 A Guide to the Microfilm Edition J. Robert Constantine Gail Malmgreen Editor Associate Editor ~ Microfilming Corporation of America A New York Times Company 1983 Cover Design by Dianne Scoggins No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microfilm, xerography, or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the copyright owner. Copyright© 1983, MICROFILMING CORPORATION OF AMERICA ISBN 0-667-00699-0 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ............................................................................ v Note to the Researcher .................................................................... vii Eugene Victor Debs (1855-1926) ........................................................