The Future of Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Delivery Brands Head-To-Head the Ordering Operation

FOOD DELIVERY BRANDS HEAD-TO-HEAD THE ORDERING OPERATION Market context: The UAE has a well-established tradition of getting everything delivered to your doorstep or to your car at the curb. So in some ways, the explosion of food delivery brands seems almost natural. But with Foodora’s recent exit from the UAE, the acquisition of Talabat by Rocket Internet, and the acquisition of Foodonclick and 24h by FoodPanda, it seemed the time was ripe to put the food delivery brands to the test. Our challenge: We compared six food delivery brands in Dubai to find the most rewarding, hassle-free ordering experience. Our approach: To evaluate the complete customer experience, we created a thorough checklist covering every facet of the service – from signing up, creating accounts, and setting up delivery addresses to testing the mobile functionality. As a control sample, we first ordered from the same restaurant (Maple Leaf, an office favorite) using all six services to get a taste for how each brand handled the same order. Then we repeated the exercise, this time ordering from different restaurants to assess the ease of discovering new places and customizing orders. To control for other variables, we placed all our orders on weekdays at 1pm. THE JUDGING PANEL 2 THE COMPETITIVE SET UAE LAUNCH OTHER MARKETS SERVED 2011 Middle East, Europe 2015 12 countries, including Hong Kong, the UK, Germany 2011 UAE only 2010 Turkey, Lebanon, Qatar 2012 GCC, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia 2015 17 countries, including India, the USA, the UK THE REVIEW CRITERIA: • Attraction: Looks at the overall design, tone of voice, community engagement, and branding. -

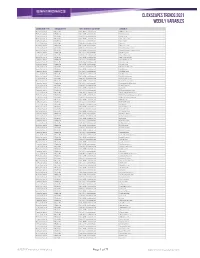

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Foodora and Deliveroo: the App As a Boss? Control and Autonomy in App-Based Management - the Case of Food Delivery Riders

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Ivanova, Mirela; Bronowicka, Joanna; Kocher, Eva; Degner, Anne Working Paper Foodora and Deliveroo: The App as a Boss? Control and autonomy in app-based management - the case of food delivery riders Working Paper Forschungsförderung, No. 107 Provided in Cooperation with: The Hans Böckler Foundation Suggested Citation: Ivanova, Mirela; Bronowicka, Joanna; Kocher, Eva; Degner, Anne (2018) : Foodora and Deliveroo: The App as a Boss? Control and autonomy in app-based management - the case of food delivery riders, Working Paper Forschungsförderung, No. 107, Hans-Böckler- Stiftung, Düsseldorf, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2019022610132332740779 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/216032 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Strategic Marketing Audit Ubereats, Brisbane

AMB359 Strategic Marketing Audit UberEATS, Brisbane Prepared for: Erin Su Prepared by: Juanita Bradford (n9013458) Word Count: 1091 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………3 1.0 Introduction………………………………………………………………4 2.0 Customer Analysis……………………………………………………..4 3.0 Competitor Analysis……………………………………………….....5 4.0 Market/Submarket Analysis………………………………………8 5.0 Environmental Analysis and Strategic Uncertainty...….9 5.1 Technological Trends………………………………………….9 5.2 Consumer Trends.………………………………………………9 5.3 Government/Economic Trends…………………………...9 5.4 Strategic Uncertainty………………………………………..10 6.0 Preliminary Strategic Options…………………………………..10 7.0 References……………………………………………………………….11 2 Executive Summary The Uber Strategic Marketing Audit is a close analysis of the current market environment for intermediate online food delivery services such as UberEATS (UE) in Brisbane. The Strategic Marketing Audit has been prepared ahead of the launch of UE in Brisbane and will present two preliminary strategic objectives in order for the firm to succeed in its entry in this new market. Firstly, the two primary target segments were identified as the most profitable and sustainable in the customer analysis the Young Professionals and the Highend Restaurants. The Young Professionals represent the service receiving segment and the Highend Restaurants represent the service offering end segment. A competitor analysis also revealed two direct competitors, Deliveroo and Foodora and three indirect competitors, Menulog, Eatnow.com and Delivery Hero. Using the Competitor Strength Grid it was revealed that UberEATS was the only direct competitor to utilise drivers and vehicles for distribution. The market and submarket analysis revealed that the overall market is relatively attractive due to promising growth. More specifically the emerging submarkets that were revealed were, vegetarianism, alcohol delivery and utilising the existing app as a search and discovery tool for consumers. -

Annual Financial Statement and Combined Management Report Delivery Hero SE As of December 31, 2018

Annual financial statement and combined management report Delivery Hero SE As of December 31, 2018 1 COMBINED MANAGEMENT REPORT COMBINED MANAGEMENT REPORT Try out our interactive table of contents. You will be directed to the selected page. COMBINED MANAGEMENT REPORT ANNUAL REPORT 2018 A. GROUP PROFILE food ordering platforms, the Group also offers own deliv- 02. CORPORATE STRATEGY ery services to restaurants without this capability. The own 01. BUSINESS MODEL delivery fleet is coordinated using proprietary dispatch Delivery Heroʼs operational success is a result of the vision software. and clear focus to create an amazing on-demand experi- The Delivery Hero SE (the “Company”) and its consolidat- ence. While food delivery is and will remain the core pillar ed subsidiaries, together Delivery Hero Group (also DH, Delivery Hero generates a large portion of its revenue from of our business, we also follow our customersʼ demands DH Group, Delivery Hero or Group), provide online and online marketplace services, primarily on the basis of forn a increasing offering of convenience services. Con- food delivery services in over 40 countries in four orders placed. These commission fees are based on a con- sumers have ever higher expectations of services like ours geographical segments, comprising Europe, Middle East tractually specified percentage of the order value. The per- and because of this we are focusing more and more on and North Africa (MENA), Asia and the Americas. centage varies depending on the country, type of restau- broader on-demand needs. We have therefore upgraded rant and services provided, such as the use of a point of our vision accordingly to: Always delivering amazing Following the conversion from a German stock corpora- sale system, last mile delivery and marketing support. -

B.C. Agrifood and Seafood Domestic Consumption Study

B.C. Agrifood and Seafood Domestic Consumption Study February 2018 Research conducted by: Research conducted for: Funding for this project has been provided by the Governments of Canada and British Columbia through Growing Forward 2, a federal-provincial-territorial initiative. Opinions expressed in this document are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Governments of Canada and British Columbia. The Governments of Canada and British Columbia, and their directors, agents, employees, or contractors will not be liable for any claims, damages, or losses of any kind whatsoever arising out of the use of, or reliance upon, this information. 2 Contents Background and Purpose of Project 5 Project Scope 6 Methodology 7 Key Takeaways 8 Market Overview 10 The Market Segments 20 Regional Profiles 42 Appendices Methodology 66 Icon Legend 71 Context Setting Report 74 Segments Details 82 3 REPORT CONTEXT Background and Purpose of Project Background • Building the local market for B.C. foods is a key focus for the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture. • This effort supports B.C. farmers, fishers, and food processors in capturing more of the local market by actively promoting B.C. products, taking advantage of the growing interest in local food. • However, there is currently limited information available within B.C. that describes the key behaviours and motivations which drive consumers to buy local, making it difficult for B.C.’s agrifood and seafood businesses to develop an action plan. Purpose To support the government plan, this project was implemented with the following objectives: • Identify consumer segments in B.C. that are currently purchasing local agrifood and seafood products; • Determine what local agrifood and seafood products they are consuming; • Uncover motivations for buying local agrifood and seafood instead of other competitive products; • Assess where they shop for local agrifood and seafood products; • Determine where key consumer segments are located in B.C.; and • Gauge the degree to which these segments are influenced by different “buy B.C. -

Economics and Taxation of Multisided Platforms

04/07/2019 Economics and Taxation of Multisided Platforms Mauro Marè Luiss University SIEP Conference on Taxation and the digitalization of the economy: state of the art and perspectives Rome, 19 June 2019 1 Outline 1. IO and Microeconomics of MP: productivity, competition, taxation … 2. The mechanics of platforms: many sides platforms, network externalities, pricing structure, elasticity, etc. 1. Why and How to tax the digital economy? 2. profits tax allocation, but also revenue tax, tax on transactions, advertising, on data, unit and ad valorem taxes, etc. 1. International issues: OECD, EU and the US Tax Reform 1 04/07/2019 2 Main issues • Strong dematerialization of economies; DE lead to a new chain value • digital economy is essentially immaterial: firms have a huge capacity to supply digital good and services without physical nexus • key role of intangibles (patents, intellectual property, algorithms, etc.). Investments essentially in intangibles: macro and micro effects • DE is leading to a vanishing of tax bases? 2 Capitalism without Capital Haskel‐Westlake (2018) For centuries, when people wanted to measure the value of a firm, they counted and measured physical stuffs. Investments were all in tangible assets Digital firms: market value is a large multiple (40‐60?) of asset valuation from balance sheet. This is “Capitalism without capital” Investment in intangible are deeply different: effects on innovation & growth, productivity, inequality, financial policy, taxation Intangibles: a) presents sunk costs; b) generate spillovers; c) are more likely to be scalable (ex. brands, licensing agreements, etc.) d) synergies …. 2 04/07/2019 3 micro of multisided platforms P Tradizional One Side (pipeline) Market S • Elasticity D and S • Pricing • Market power and monopoly • Deadweight loss (inefficiency) D Q 3 Multisided Platforms • MPs create new (non‐existing) markets in many sectors, with two or more parts. -

Global Consumer Survey List of Brands June 2018

Global Consumer Survey List of Brands June 2018 Brand Global Consumer Indicator Countries 11pingtai Purchase of online video games by brand / China stores (past 12 months) 1688.com Online purchase channels by store brand China (past 12 months) 1Hai Online car rental bookings by provider (past China 12 months) 1qianbao Usage of mobile payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) 1qianbao Usage of online payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) 2Checkout Usage of online payment methods by brand Austria, Canada, Germany, (past 12 months) Switzerland, United Kingdom, USA 7switch Purchase of eBooks by provider (past 12 France months) 99Bill Usage of mobile payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) 99Bill Usage of online payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) A&O Grocery shopping channels by store brand Italy A1 Smart Home Ownership of smart home devices by brand Austria Abanca Primary bank by provider Spain Abarth Primarily used car by brand all countries Ab-in-den-urlaub Online package holiday bookings by provider Austria, Germany, (past 12 months) Switzerland Academic Singles Usage of online dating by provider (past 12 Italy months) AccorHotels Online hotel bookings by provider (past 12 France months) Ace Rent-A-Car Online car rental bookings by provider (past United Kingdom, USA 12 months) Acura Primarily used car by brand all countries ADA Online car rental bookings by provider (past France 12 months) ADEG Grocery shopping channels by store brand Austria adidas Ownership of eHealth trackers / smart watches Germany by brand adidas Purchase of apparel by brand Austria, Canada, China, France, Germany, Italy, Statista Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel. -

Instant Deliveries’ in European Cities Laetitia Dablanc, Eléonora Morganti, Niklas Arvidsson, Johan Woxenius, Michael Browne, Neila Saidi

The Rise of On-Demand ’Instant Deliveries’ in European Cities Laetitia Dablanc, Eléonora Morganti, Niklas Arvidsson, Johan Woxenius, Michael Browne, Neila Saidi To cite this version: Laetitia Dablanc, Eléonora Morganti, Niklas Arvidsson, Johan Woxenius, Michael Browne, et al.. The Rise of On-Demand ’Instant Deliveries’ in European Cities. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal, Kedge Business School, 2017, 10.1080/16258312.2017.1375375. hal-01589316 HAL Id: hal-01589316 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01589316 Submitted on 18 Sep 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Forthcoming in Supply Chain Forum – an International Journal The Rise of On-Demand ‘Instant Deliveries’ in European Cities Laetitia Dablanc,a and d, 1 Eleonora Morganti,b Niklas Arvidsson,c Johan Woxenius,d Michael Browne,d Neïla Saidie aIFSTTAR-University of Paris-East, 14 Bd Newton, 77455 Marne la Vallée, France bUniversity of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, United Kingdom cRISE Viktoria Research Institute, Lindholmspiren 3A, SE-417 56, Gothenburg, Sweden dUniversity of Gothenburg, Box 610, SE-405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden eArchitectural School of Marne la Vallée, University of Paris-East, 10 avenue Blaise Pascal, 77455 Marne la Vallée, France Abstract This exploratory paper contributes to a new body of research that investigates the potential of digital market places to disrupt transport and mobility services. -

Digital Marketing for Restaurants

Department of Business and Management Three-year Degree Course in Economics and Management Chair of Digital Marketing Transformation & Customer Experience DIGITAL MARKETING AS AN ESSENTIAL TOOL FOR RESTAURANTS’ SURVIVAL IN AN EVER-CHANGING FUTURE THESIS SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Prof. Donatella Padua Barbara Epifani SN: 221131 ACADEMIC YEAR 2019/2020 1 Index Introduction: ............................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter one: Different types of restaurants............................................................................ 4 1.1 - Family restaurants ................................................................................................. 4 1.2 - Food chains, fast-foods and franchising .................................................................... 8 1.3 - Delivery and street food ............................................................................................ 11 Chapter 2: Pre and post-COVID-19 ...................................................................................... 16 2.1- The before and after of restaurant in general ......................................................... 16 2.2 - Food delivery .............................................................................................................. 20 2.3 - Street food .................................................................................................................. 24 CHAPTER 3: Digital marketing for restaurants ................................................................. -

It's the Algorithm, It Decides: an Autoethnographic Exploration Of

It’s the Algorithm, It Decides: An Autoethnographic Exploration of Algorithmic Systems of Management In On-Demand Food Delivery Work in Amsterdam In Partial Fulfillment of: Master of Arts in Media Studies New Media and Digital Culture Written by: Under the Supervision of: Date of Submission: Emma Knight Dr. Niels van Doorn June 28, 2019 ID: 12149888 Second Reader: Dr. Thomas Poell Knight 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Chapter 1 | Introduction 5 Chapter 2 | The Origins of Platform Labor & Algorithmic Management 7 2.1 Surveying the Platform Landscape 7 2.2 The Rise of Workforce Capture 11 2.3 Algorithmic Management in Platform Labor 16 2.4 Developing Algorithmic Competencies 20 Chapter 3 | Methodological Framework 23 3.1 The Current Landscape of On-Demand Food Delivery Platforms 23 3.1.1 Deliveroo 24 3.1.2 Uber Eats 25 3.2 Qualitative Research Design 27 3.3 Onboarding Process 30 3.4 Interview Protocol 31 3.5 Rider Recruitment Strategies 32 3.6 Overview of Participants 33 3.7 Ethical Protections for Participants 33 3.8 Limitations of Research Design 34 Chapter 4 | The Generation of Algorithmic Knowledge 37 4.1 Capture in the Context of Deliveroo and Uber Eats 37 4.2 Deliveroo’s Shift Booking Algorithm 40 4.3 Order Assignment Algorithms 43 4.4 Dynamic Pricing Algorithm 48 4.5 Algorithmic Limitations and Automated Errors 52 Chapter 5 | Conclusion 57 References 60 Knight 3 Abstract Companies that operate in the ‘on-demand’ platform or ‘gig’ economy rely upon machine-learning algorithms to facilitate interactions between service providers and customers. -

How On-Demand Deliveries in Cities Change Services and Jobs: New Survey Results

METRANS Seminar, USC, July 23, 2018 How on-demand deliveries in cities change services and jobs: new survey results Laetitia Dablanc IFSTTAR, French Institute for Transport Research, University of Paris East Metrofreight/USC • The presentation in brief: 1. Demand for fast deliveries (same day and ‘instant’) increases, especially in cities 2. It has impacts on jobs, on the way freight services are provided 3. It has impacts on the city environment and on urban planning 4. New survey results provide some knowledge, data collection to be developed 17.2% people living in Manhattan use same day deliveries at least once a month 6T bureau de recherche, survey Dec 2017, to be published NYC = mostly Manhattan Paris = City of Paris Does not include food apps 31.8% people living in Manhattan use a food app at least once a week 6T bureau de recherche, survey Dec 2017, to be published NYC = mostly Manhattan Paris = City of Paris More use of instant delivery apps in urban China (same day incl. food apps) FT Research year of data 2017 Methodology • Instant deliveries = on-demand deliveries within two hours provided by connecting shippers, couriers and consumers via a digital platform • Data collection on companies (Europe, US & Asia) from specialized press, literature, websites and some interviews with managers • 2016 and 2018 surveys among couriers in Paris • Face to face and online questionnaire interviews - only face to face interviews reported in results here • Face to face interviews were chance encounters in Paris streets, about one hour with