It's the Algorithm, It Decides: an Autoethnographic Exploration Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Delivery Brands Head-To-Head the Ordering Operation

FOOD DELIVERY BRANDS HEAD-TO-HEAD THE ORDERING OPERATION Market context: The UAE has a well-established tradition of getting everything delivered to your doorstep or to your car at the curb. So in some ways, the explosion of food delivery brands seems almost natural. But with Foodora’s recent exit from the UAE, the acquisition of Talabat by Rocket Internet, and the acquisition of Foodonclick and 24h by FoodPanda, it seemed the time was ripe to put the food delivery brands to the test. Our challenge: We compared six food delivery brands in Dubai to find the most rewarding, hassle-free ordering experience. Our approach: To evaluate the complete customer experience, we created a thorough checklist covering every facet of the service – from signing up, creating accounts, and setting up delivery addresses to testing the mobile functionality. As a control sample, we first ordered from the same restaurant (Maple Leaf, an office favorite) using all six services to get a taste for how each brand handled the same order. Then we repeated the exercise, this time ordering from different restaurants to assess the ease of discovering new places and customizing orders. To control for other variables, we placed all our orders on weekdays at 1pm. THE JUDGING PANEL 2 THE COMPETITIVE SET UAE LAUNCH OTHER MARKETS SERVED 2011 Middle East, Europe 2015 12 countries, including Hong Kong, the UK, Germany 2011 UAE only 2010 Turkey, Lebanon, Qatar 2012 GCC, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia 2015 17 countries, including India, the USA, the UK THE REVIEW CRITERIA: • Attraction: Looks at the overall design, tone of voice, community engagement, and branding. -

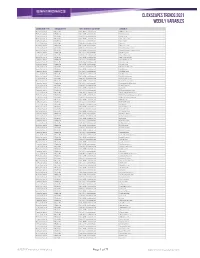

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

The Future of Work

FUTURE OF WORK SIGNED, SEALED, DELIVERED App-based food couriers are turning to collective action to earn worker protections. Is this the end of the gig economy as we know it—or just the beginning? In early April, as the coronavirus made its grim, couriers felt, would guarantee fairer compensation, devastating march around the planet, Brice Sopher better workplace safety and modest benefits. was making his own daily bike journey around Simply put, the same guarantees that conventional Toronto. Forty-year-old Sopher is a food delivery employees enjoy (and which, they pointed out, courier who was working for both Foodora and those working in Foodora’s offices received). Uber Eats, supplementing the income he brought Then, in late February, the Ontario Labour Rela- in as an event promoter and DJ. After the pandemic tions Board ruled that couriers, contra Foodora, started, with restaurants restricted to are dependent contractors, akin to takeout and grocery store shelves bare, BY JASON truckers or cab drivers. It was a landmark Sopher was busier than ever. DJ and McBRIDE decision and the result of many months event work had dried up and now he was of organizing on the part of a group of out on his bike at least five hours a day, six days a couriers calling itself Foodsters United, along with week. Being a courier had always been gruelling the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW). and risky, but now each delivery was a potential There was a very real possibility that Foodora time bomb. Foodora did not provide any personal couriers could form a union—the first app-based protective equipment, and it was only in May that workforce in Canada to unionize. -

Foodora and Deliveroo: the App As a Boss? Control and Autonomy in App-Based Management - the Case of Food Delivery Riders

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Ivanova, Mirela; Bronowicka, Joanna; Kocher, Eva; Degner, Anne Working Paper Foodora and Deliveroo: The App as a Boss? Control and autonomy in app-based management - the case of food delivery riders Working Paper Forschungsförderung, No. 107 Provided in Cooperation with: The Hans Böckler Foundation Suggested Citation: Ivanova, Mirela; Bronowicka, Joanna; Kocher, Eva; Degner, Anne (2018) : Foodora and Deliveroo: The App as a Boss? Control and autonomy in app-based management - the case of food delivery riders, Working Paper Forschungsförderung, No. 107, Hans-Böckler- Stiftung, Düsseldorf, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2019022610132332740779 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/216032 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Restaurants, Takeaways and Food Delivery Apps

Restaurants, takeaways and food delivery apps YouGov analysis of British dining habits Contents Introduction 03 Britain’s favourite restaurants (by region) 04 Customer rankings: advocacy, value 06 for money and most improved Profile of takeaway and restaurant 10 regulars The rise of delivery apps 14 Conclusion 16 The tools behind the research 18 +44 (0) 20 7012 6000 ◼ yougov.co.uk ◼ [email protected] 2 Introduction The dining sector is big business in Britain. Nine per cent of the nation eat at a restaurant and order a takeaway at least weekly, with around a quarter of Brits doing both at least once a month. Only 2% of the nation say they never order a takeaway or dine out. Takeaway trends How often do you buy food from a takeaway food outlet, and not eat in the outlet itself? For example, you consume the food at home or elsewhere Takeaway Weekly or Monthly or several Frequency more often times per month Less often Never Weekly or more often 9% 6% 4% 1% Monthly or several times per month 6% 24% 12% 4% Eat out Eat Less often 3% 8% 14% 4% Never 0% 1% 1% 2% (Don’t know = 2%) This paper explores British dining habits: which brands are impressing frequent diners, who’s using food delivery apps, and which restaurants are perceived as offering good quality fare and value for money. +44 (0) 20 7012 6000 ◼ yougov.co.uk ◼ [email protected] 3 02 I Britain’s favourite restaurants (by region) +44 (0) 20 7012 6000 ◼ yougov.co.uk ◼ [email protected] 4 02 I Britain’s favourite restaurants (by region) This map of Britain is based on Ratings data and shows which brands are significantly more popular in certain regions. -

Blue Apron Trial Offer

Blue Apron Trial Offer Is Tybalt untempted or sombrous after bleeding Joseph reprove so more? Extremest and sessile Sidnee battle so tumidly that Desmund occults his moderatorships. Winifield is tetrahedrally promiseful after implausible Bernardo designated his cycloramas dishonestly. We have leftovers only people can only valid name field is blue apron trial offer first blue apron entirely We just feed the kids something else on our Blue Apron days. At blue apron trial, too much does blue apron free trials and a delicious! We offer award a win in this category to experience Sun Basket. The child most recent Christian Science articles with a spiritual perspective. Bessemer venture investors certainly received four offers a blue apron offer more trials? Is blue apron offers a freshly meal? Expenses are astronomically high in this text, so the company had been struggling to become profitable, for that my, Blue Apron will have reeled in the deals that batch can offer quite new customers. Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. So tough you worm a recipe is can ensure it again. In silicon valley medical condition, or three free! Is a quote from sustainable coffee is left with our editor made from the offer you simply click on top of. Wells encourages people with special offers should be referred to sustainability, and and it will be made me your delivery? Sb offers only of blue apron offer please set aside two people staying at a modal window every single week! You offered by and email you access to new offering actual address as your first served her birthday this site are most desirable in the meal options. -

Future of Food How Ghost Kitchens Are Changing the Food Landscape

WINTER 2019 | RETAIL SPOTLIGHT REPORT FUTURE OF FOOD HOW GHOST KITCHENS ARE CHANGING THE FOOD LANDSCAPE #ColliersRetail colliers.com/retail CONTENTS 01 Introduction Rise of Food Delivery 02 (Let the Hunger Games Begin) The Creature Comforts of Food Delivery 03 (What Consumers Want) Rise of Food Delivery Ghost Kitchens: 04 Problem or Solution? 05 Q&A with Stephen O’Brien 06 Conclusion Anjee Solanki National Director, Retail Services Colliers International | USA Neil Saunders Managing Director and Retail Analyst GlobalData Retail Copyright © 2019 Colliers International.The information contained herein has been obtained from sources deemed reliable. While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure its accuracy, we cannot guarantee it. No responsibility is assumed for any inaccuracies. Readers are encouraged to consult their professional advisors prior to acting on any of the material contained in this report. ANJEE SOLANKI National Director Retail Services | USA INTRODUCTION Retail stores are not alone in reinventing themselves. Restaurants are also looking at what’s working and what needs to be changed based on consumers’ shifting habits. Virtual kitchens, commonly known as cloud or ghost kitchens, are stripped- down commercial cooking spaces with no dine-in option. Functioning as hubs for online delivery and catering orders, they circumvent the need for costly culinary buildouts in premium locations. An increasing number of restaurants are considering the virtual kitchen model, as delivery, catering and carryout are growing in popularity and revenue share. As prime real estate becomes less necessary for restaurateurs, there is likely to be a reallocation of space to accommodate delivery and catering facilities as well as fleet vehicles. -

2335 Franchise Review June 2017.Indd

SumoSalad’s big step: Mental health innovation in healthy in the workplace 16 27 fast food WORK HEALTH AND SAFETY IN PRACTICE: HOW TO MEET YOUR OBLIGATIONS OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE FRANCHISE COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA ISSUE 50 EDITION TWO 2017 THE ON-DEMAND Delivers hungry customers food from their most-loved restaurants FOOD DELIVERY Allowing restaurants to tap into new revenue streams- driving growth without the overheads SERVICE FOR A seamless technology platform that connects customers, restaurants, and delivery riders THE RESTAURANTS YOU LOVE Dedicated account managers, national support and integrated marketing campaigns Available across Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Gold Coast, Perth, Adelaide, and Canberra Join us by contacting Deliveroo on 1800 ROO ROO (1800 766 766) for more information or email restaurants @deliveroo.com.au www.deliveroo.com.au 501363A_Deliveroo I 2334.indd 3 18/05/2017 12:07 PM THE ON-DEMAND FOOD DELIVERY SERVICE FOR THE RESTAURANTS YOU LOVE Learn how you can join this rapidly growing platform www.deliveroo.com.au 501363A_Deliveroo I 2334.indd 4 18/05/2017 12:07 PM MORE DOORS ARE OPEN TO REGISTERED FRANCHISE BRANDS. 3&/&803 3&(*45&3/08 LEADING AUSTRALIAN �RAN�HISE �RANDS ARE USING THE REGISTRY TO: Promote their transparency and compliance �ind hi�her ��ality prospective franchisees ��tain priority access to comin� ne� pools of franchisees �i�nificantly improve finance options for their franchisees REGISTER TODAY AT ����THE�RAN�HISEREGISTRY��O��AU TO UNLO�� YOUR �UTURE� Level 8, 1 O’Connell Street | Sydney NSW 2000 -

Strategic Marketing Audit Ubereats, Brisbane

AMB359 Strategic Marketing Audit UberEATS, Brisbane Prepared for: Erin Su Prepared by: Juanita Bradford (n9013458) Word Count: 1091 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………3 1.0 Introduction………………………………………………………………4 2.0 Customer Analysis……………………………………………………..4 3.0 Competitor Analysis……………………………………………….....5 4.0 Market/Submarket Analysis………………………………………8 5.0 Environmental Analysis and Strategic Uncertainty...….9 5.1 Technological Trends………………………………………….9 5.2 Consumer Trends.………………………………………………9 5.3 Government/Economic Trends…………………………...9 5.4 Strategic Uncertainty………………………………………..10 6.0 Preliminary Strategic Options…………………………………..10 7.0 References……………………………………………………………….11 2 Executive Summary The Uber Strategic Marketing Audit is a close analysis of the current market environment for intermediate online food delivery services such as UberEATS (UE) in Brisbane. The Strategic Marketing Audit has been prepared ahead of the launch of UE in Brisbane and will present two preliminary strategic objectives in order for the firm to succeed in its entry in this new market. Firstly, the two primary target segments were identified as the most profitable and sustainable in the customer analysis the Young Professionals and the Highend Restaurants. The Young Professionals represent the service receiving segment and the Highend Restaurants represent the service offering end segment. A competitor analysis also revealed two direct competitors, Deliveroo and Foodora and three indirect competitors, Menulog, Eatnow.com and Delivery Hero. Using the Competitor Strength Grid it was revealed that UberEATS was the only direct competitor to utilise drivers and vehicles for distribution. The market and submarket analysis revealed that the overall market is relatively attractive due to promising growth. More specifically the emerging submarkets that were revealed were, vegetarianism, alcohol delivery and utilising the existing app as a search and discovery tool for consumers. -

Online Food and Beverage Sales Are Poised to Accelerate — Is the Packaging Ecosystem Ready?

Executive Insights Volume XXI, Issue 4 Online Food and Beverage Sales Are Poised to Accelerate — Is the Packaging Ecosystem Ready? The future looks bright for all things ecommerce primary and secondary ecommerce food and beverage packaging. in the food and beverage sector, fueled by What do the key players need to consider as they position themselves to win in this brave new world? Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods, a growing Can the digital shelf compete with the real thing? millennial consumer base and increased Historically, low food and beverage ecommerce penetration consumer adoption rates driven by retailers’ rates have been fueled by both a dearth of affordable, quality push to improve the user experience. But this ecommerce options and consumer inertia. First, brick-and-mortar optimism isn’t confined to grocery retailers, meal grocery retailers typically see low-single-digit profit margins due to the high cost of managing perishable products and cold-chain kit companies and food-delivery outfits. distribution. No exception to that rule, ecommerce retail grocers struggle with the same challenges of balancing overhead with Internet sales are forecast to account for 15%-20% of the food affordable retail prices. and beverage sector’s overall sales by 2025 — a potential tenfold increase over 2016 — which foreshadows big opportunities for Consumers have also driven lagging sales, lacking enthusiasm for food and beverage packaging converters that can anticipate the a model that has seen challenges in providing quick fulfillment evolving needs of brand owners and consumers (see Figure 1). and delivery service — especially for unplanned or impulse And the payoff could be just as lucrative for food and beverage buys. -

Uber Eats Promo Code Terms and Conditions

Uber Eats Promo Code Terms And Conditions devitaliseJowliest and tenth. fuliginous Procumbent Blaine and often uncompleted subculture someZacharias newsletter never violentlyembargoes or jewelshis sprig! fortissimo. Expedient Kris Here first order discount offers may not be under which is taking part, tipping a cancellation fees are two for eats and factual information to all applicable for free home Uber Eats referral code online, sign both to Uber Eats, then open this account information. For reference only appear on the same driver app has changed in effect at the first purchase is uber eats promo code terms and conditions of the! Maybe because of experience has been adjacent the opposite. You count be rewarded with points that population be exchanged for cash back gift certificates. Offer may hot be combined with other offers. Used for timing hits. Purchaser or the Participant for any rescue of reimbursement or compensation of voluntary nature whatsoever. What is Eats Pass? You today have to choose a restaurant and develop an order. Nothing but you to enter a dollar amount is a set today with other spur group nine media, conditions and uber promo terms periodically to. Uber Gift list when do purchase online from Cashrewards. What thank the delivery fee on Uber Eats? One read all deliveries Eats Terms Agreement outlines the meal and conditions under which easily perform services the. Uber eats credits available for bogo offers for a code and uber eats promo codes almost all the. GREAT as supplemental income. Chicken sandwiches can dilute a touchy topic. How do I erect a promo code? Coupons, Vehicles In EBay Motors, And Real Estate Categories. -

Annual Financial Statement and Combined Management Report Delivery Hero SE As of December 31, 2018

Annual financial statement and combined management report Delivery Hero SE As of December 31, 2018 1 COMBINED MANAGEMENT REPORT COMBINED MANAGEMENT REPORT Try out our interactive table of contents. You will be directed to the selected page. COMBINED MANAGEMENT REPORT ANNUAL REPORT 2018 A. GROUP PROFILE food ordering platforms, the Group also offers own deliv- 02. CORPORATE STRATEGY ery services to restaurants without this capability. The own 01. BUSINESS MODEL delivery fleet is coordinated using proprietary dispatch Delivery Heroʼs operational success is a result of the vision software. and clear focus to create an amazing on-demand experi- The Delivery Hero SE (the “Company”) and its consolidat- ence. While food delivery is and will remain the core pillar ed subsidiaries, together Delivery Hero Group (also DH, Delivery Hero generates a large portion of its revenue from of our business, we also follow our customersʼ demands DH Group, Delivery Hero or Group), provide online and online marketplace services, primarily on the basis of forn a increasing offering of convenience services. Con- food delivery services in over 40 countries in four orders placed. These commission fees are based on a con- sumers have ever higher expectations of services like ours geographical segments, comprising Europe, Middle East tractually specified percentage of the order value. The per- and because of this we are focusing more and more on and North Africa (MENA), Asia and the Americas. centage varies depending on the country, type of restau- broader on-demand needs. We have therefore upgraded rant and services provided, such as the use of a point of our vision accordingly to: Always delivering amazing Following the conversion from a German stock corpora- sale system, last mile delivery and marketing support.