The Collective Visibility of Couriers Or the Beginnings of a New Social Contract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Delivery Brands Head-To-Head the Ordering Operation

FOOD DELIVERY BRANDS HEAD-TO-HEAD THE ORDERING OPERATION Market context: The UAE has a well-established tradition of getting everything delivered to your doorstep or to your car at the curb. So in some ways, the explosion of food delivery brands seems almost natural. But with Foodora’s recent exit from the UAE, the acquisition of Talabat by Rocket Internet, and the acquisition of Foodonclick and 24h by FoodPanda, it seemed the time was ripe to put the food delivery brands to the test. Our challenge: We compared six food delivery brands in Dubai to find the most rewarding, hassle-free ordering experience. Our approach: To evaluate the complete customer experience, we created a thorough checklist covering every facet of the service – from signing up, creating accounts, and setting up delivery addresses to testing the mobile functionality. As a control sample, we first ordered from the same restaurant (Maple Leaf, an office favorite) using all six services to get a taste for how each brand handled the same order. Then we repeated the exercise, this time ordering from different restaurants to assess the ease of discovering new places and customizing orders. To control for other variables, we placed all our orders on weekdays at 1pm. THE JUDGING PANEL 2 THE COMPETITIVE SET UAE LAUNCH OTHER MARKETS SERVED 2011 Middle East, Europe 2015 12 countries, including Hong Kong, the UK, Germany 2011 UAE only 2010 Turkey, Lebanon, Qatar 2012 GCC, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia 2015 17 countries, including India, the USA, the UK THE REVIEW CRITERIA: • Attraction: Looks at the overall design, tone of voice, community engagement, and branding. -

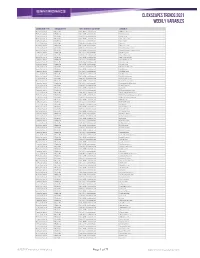

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Pre-Feasibility Analysis for the Creation of a Delivery Company in a Context of Great Competition

PRE-FEASIBILITY ANALYSIS FOR THE CREATION OF A DELIVERY COMPANY IN A CONTEXT OF GREAT COMPETITION Alberto Barrera Valdeolivas, s265308 11 DICEMBRE 2020 AMAZON CORPORATE Relatore: Maurizio Schenone Credits To Alice, the light of my life, the one that has given me so many good moments and has helped me so much in the last 3 years. To my family: my parents, my sister, my grandparents ... they are the greatest thing I have. To my Italian family, who have always shown me to be one more and have welcomed me from the first moment I arrived To my roommates in Turin: Pol, Sergio, Barbany and Marc. They gave me two of the best years of my life and unforgettable moments. Ai miei fratelli Stenis, Matteo e le mie grandi amiche Chiri, Cecilia and Giulia. To Kobe, the very new member of the family, we are so proud and happy to have you in our lives. 1 Index 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Origin and Motivation ...................................................................................... 4 1.2 Aims and Scope ................................................................................................ 5 1.3 Structure of the document ................................................................................ 6 2 Context ........................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Actual Delivery System .................................................................................. -

Glovo Scales and Delivers with Makemereach 60% 24%

Glovo scales and delivers with MakeMeReach CASE STUDY Glovo delivers any local product to your door in an average of 30 mins. From electronics, to food, to flowers, Glovo fills the gap between offline and online commerce - on demand and on mobile. Scale quickly In Spain, Glovo has relied on the MakeMeReach solution as a crucial pillar in their scale-up strategy throughout the spanish-speaking world. In September 2017, after roughly two-and-a-half years in business, Glovo decided it was time to scale quickly. In just over a year they’ve added more than 100 cities, and are now active in 22 countries worldwide. Added to that, they’ve multiplied their number or orders delivered by 10 - from 1 million in September 2017, to over 10 million in late 2018. Targeting approach To achieve this kind of growth, Glovo have had to be smart about how they establish their activity in new cities. Their business model is such that they are not only interested in acquiring new users of the service, but also new delivery people (called ‘Glovers’) in each new city. To get both users and Glovers on board, and ensure each new location started off with a bang, Glovo followed a two-stage targeting approach for their Facebook and Instagram advertising campaigns: In the first stage, focusing on individual suburbs at a time, Glovo used broad targeting to Then, in the second reach males and females stage, they built on this aged 20-54 years old. initial audience with lookalikes and additional interest-based groups. -

The Future of Work

FUTURE OF WORK SIGNED, SEALED, DELIVERED App-based food couriers are turning to collective action to earn worker protections. Is this the end of the gig economy as we know it—or just the beginning? In early April, as the coronavirus made its grim, couriers felt, would guarantee fairer compensation, devastating march around the planet, Brice Sopher better workplace safety and modest benefits. was making his own daily bike journey around Simply put, the same guarantees that conventional Toronto. Forty-year-old Sopher is a food delivery employees enjoy (and which, they pointed out, courier who was working for both Foodora and those working in Foodora’s offices received). Uber Eats, supplementing the income he brought Then, in late February, the Ontario Labour Rela- in as an event promoter and DJ. After the pandemic tions Board ruled that couriers, contra Foodora, started, with restaurants restricted to are dependent contractors, akin to takeout and grocery store shelves bare, BY JASON truckers or cab drivers. It was a landmark Sopher was busier than ever. DJ and McBRIDE decision and the result of many months event work had dried up and now he was of organizing on the part of a group of out on his bike at least five hours a day, six days a couriers calling itself Foodsters United, along with week. Being a courier had always been gruelling the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW). and risky, but now each delivery was a potential There was a very real possibility that Foodora time bomb. Foodora did not provide any personal couriers could form a union—the first app-based protective equipment, and it was only in May that workforce in Canada to unionize. -

Foodora and Deliveroo: the App As a Boss? Control and Autonomy in App-Based Management - the Case of Food Delivery Riders

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Ivanova, Mirela; Bronowicka, Joanna; Kocher, Eva; Degner, Anne Working Paper Foodora and Deliveroo: The App as a Boss? Control and autonomy in app-based management - the case of food delivery riders Working Paper Forschungsförderung, No. 107 Provided in Cooperation with: The Hans Böckler Foundation Suggested Citation: Ivanova, Mirela; Bronowicka, Joanna; Kocher, Eva; Degner, Anne (2018) : Foodora and Deliveroo: The App as a Boss? Control and autonomy in app-based management - the case of food delivery riders, Working Paper Forschungsförderung, No. 107, Hans-Böckler- Stiftung, Düsseldorf, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2019022610132332740779 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/216032 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Food Delivery Platforms: Will They Eat the Restaurant Industry's Lunch?

Food Delivery Platforms: Will they eat the restaurant industry’s lunch? On-demand food delivery platforms have exploded in popularity across both the emerging and developed world. For those restaurant businesses which successfully cater to at-home consumers, delivery has the potential to be a highly valuable source of incremental revenues, albeit typically at a lower margin. Over the longer term, the concentration of customer demand through the dominant ordering platforms raises concerns over the bargaining power of these platforms, their singular control of customer data, and even their potential for vertical integration. Nonetheless, we believe that restaurant businesses have no choice but to embrace this high-growth channel whilst working towards the ideal long-term solution of in-house digital ordering capabilities. Contents Introduction: the rise of food delivery platforms ........................................................................... 2 Opportunities for Chained Restaurant Companies ........................................................................ 6 Threats to Restaurant Operators .................................................................................................... 8 A suggested playbook for QSR businesses ................................................................................... 10 The Arisaig Approach .................................................................................................................... 13 Disclaimer .................................................................................................................................... -

Strategic Marketing Audit Ubereats, Brisbane

AMB359 Strategic Marketing Audit UberEATS, Brisbane Prepared for: Erin Su Prepared by: Juanita Bradford (n9013458) Word Count: 1091 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………3 1.0 Introduction………………………………………………………………4 2.0 Customer Analysis……………………………………………………..4 3.0 Competitor Analysis……………………………………………….....5 4.0 Market/Submarket Analysis………………………………………8 5.0 Environmental Analysis and Strategic Uncertainty...….9 5.1 Technological Trends………………………………………….9 5.2 Consumer Trends.………………………………………………9 5.3 Government/Economic Trends…………………………...9 5.4 Strategic Uncertainty………………………………………..10 6.0 Preliminary Strategic Options…………………………………..10 7.0 References……………………………………………………………….11 2 Executive Summary The Uber Strategic Marketing Audit is a close analysis of the current market environment for intermediate online food delivery services such as UberEATS (UE) in Brisbane. The Strategic Marketing Audit has been prepared ahead of the launch of UE in Brisbane and will present two preliminary strategic objectives in order for the firm to succeed in its entry in this new market. Firstly, the two primary target segments were identified as the most profitable and sustainable in the customer analysis the Young Professionals and the Highend Restaurants. The Young Professionals represent the service receiving segment and the Highend Restaurants represent the service offering end segment. A competitor analysis also revealed two direct competitors, Deliveroo and Foodora and three indirect competitors, Menulog, Eatnow.com and Delivery Hero. Using the Competitor Strength Grid it was revealed that UberEATS was the only direct competitor to utilise drivers and vehicles for distribution. The market and submarket analysis revealed that the overall market is relatively attractive due to promising growth. More specifically the emerging submarkets that were revealed were, vegetarianism, alcohol delivery and utilising the existing app as a search and discovery tool for consumers. -

Annual Financial Statement and Combined Management Report Delivery Hero SE As of December 31, 2018

Annual financial statement and combined management report Delivery Hero SE As of December 31, 2018 1 COMBINED MANAGEMENT REPORT COMBINED MANAGEMENT REPORT Try out our interactive table of contents. You will be directed to the selected page. COMBINED MANAGEMENT REPORT ANNUAL REPORT 2018 A. GROUP PROFILE food ordering platforms, the Group also offers own deliv- 02. CORPORATE STRATEGY ery services to restaurants without this capability. The own 01. BUSINESS MODEL delivery fleet is coordinated using proprietary dispatch Delivery Heroʼs operational success is a result of the vision software. and clear focus to create an amazing on-demand experi- The Delivery Hero SE (the “Company”) and its consolidat- ence. While food delivery is and will remain the core pillar ed subsidiaries, together Delivery Hero Group (also DH, Delivery Hero generates a large portion of its revenue from of our business, we also follow our customersʼ demands DH Group, Delivery Hero or Group), provide online and online marketplace services, primarily on the basis of forn a increasing offering of convenience services. Con- food delivery services in over 40 countries in four orders placed. These commission fees are based on a con- sumers have ever higher expectations of services like ours geographical segments, comprising Europe, Middle East tractually specified percentage of the order value. The per- and because of this we are focusing more and more on and North Africa (MENA), Asia and the Americas. centage varies depending on the country, type of restau- broader on-demand needs. We have therefore upgraded rant and services provided, such as the use of a point of our vision accordingly to: Always delivering amazing Following the conversion from a German stock corpora- sale system, last mile delivery and marketing support. -

B.C. Agrifood and Seafood Domestic Consumption Study

B.C. Agrifood and Seafood Domestic Consumption Study February 2018 Research conducted by: Research conducted for: Funding for this project has been provided by the Governments of Canada and British Columbia through Growing Forward 2, a federal-provincial-territorial initiative. Opinions expressed in this document are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Governments of Canada and British Columbia. The Governments of Canada and British Columbia, and their directors, agents, employees, or contractors will not be liable for any claims, damages, or losses of any kind whatsoever arising out of the use of, or reliance upon, this information. 2 Contents Background and Purpose of Project 5 Project Scope 6 Methodology 7 Key Takeaways 8 Market Overview 10 The Market Segments 20 Regional Profiles 42 Appendices Methodology 66 Icon Legend 71 Context Setting Report 74 Segments Details 82 3 REPORT CONTEXT Background and Purpose of Project Background • Building the local market for B.C. foods is a key focus for the B.C. Ministry of Agriculture. • This effort supports B.C. farmers, fishers, and food processors in capturing more of the local market by actively promoting B.C. products, taking advantage of the growing interest in local food. • However, there is currently limited information available within B.C. that describes the key behaviours and motivations which drive consumers to buy local, making it difficult for B.C.’s agrifood and seafood businesses to develop an action plan. Purpose To support the government plan, this project was implemented with the following objectives: • Identify consumer segments in B.C. that are currently purchasing local agrifood and seafood products; • Determine what local agrifood and seafood products they are consuming; • Uncover motivations for buying local agrifood and seafood instead of other competitive products; • Assess where they shop for local agrifood and seafood products; • Determine where key consumer segments are located in B.C.; and • Gauge the degree to which these segments are influenced by different “buy B.C. -

Mih Food Delivery Holdings/Just Eat

Dirección de Competencia INFORME Y PROPUESTA DE RESOLUCIÓN EXPEDIENTE C/1072/19 MIH FOOD DELIVERY HOLDINGS/JUST EAT I. ANTECEDENTES (1) Con fecha 7 de noviembre de 2019, ha tenido entrada en la Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia (en adelante, CNMC) notificación de la operación de concentración consistente en la adquisición por parte de MIH FOOD DELIVERY HOLDINGS B.V. (MIH), del control exclusivo de JUST EAT plc (JUST EAT) a través de una oferta pública de adquisición hostil anunciada el 22 de octubre de 2019. Esta OPA hostil compite con la operación que ya se autorizó en el marco de la operación C/1046/19TAKE AWAY/JUST EAT1. Esta notificación ha dado lugar al expediente C/1072/19. (2) La notificación ha sido realizada, según lo establecido en el artículo 9 de la Ley 15/2007, de 3 de julio, de Defensa de la Competencia (“LDC”), por superar el umbral establecido en la letra a) del artículo 8.1 de la mencionada norma. A esta operación le es de aplicación lo previsto en el Reglamento de Defensa de la Competencia (“RDC”), aprobado por el Real Decreto 261/2008, de 22 de febrero. (3) Con fecha 8 de noviembre de 2019, esta Dirección de Competencia, conforme a lo previsto en los artículos 39.1.y 55.6 de la LDC, notificó a un tercer operador un requerimiento de información necesario para la adecuada valoración de la concentración, cuya respuesta fue recibida en la CNMC el 22 de noviembre de 2019. (4) Con fecha 4 de diciembre de 2019 esta Dirección de Competencia recibió dos versiones sucesivas de propuestas de compromisos (propuesta de compromisos y propuesta de compromisos actualizada) en primera fase al amparo del artículo 59 de la LDC y el artículo 69 del RDC, al objeto de resolver los posibles obstáculos para el mantenimiento de la competencia efectiva que puedan derivarse de la concentración. -

Economics and Taxation of Multisided Platforms

04/07/2019 Economics and Taxation of Multisided Platforms Mauro Marè Luiss University SIEP Conference on Taxation and the digitalization of the economy: state of the art and perspectives Rome, 19 June 2019 1 Outline 1. IO and Microeconomics of MP: productivity, competition, taxation … 2. The mechanics of platforms: many sides platforms, network externalities, pricing structure, elasticity, etc. 1. Why and How to tax the digital economy? 2. profits tax allocation, but also revenue tax, tax on transactions, advertising, on data, unit and ad valorem taxes, etc. 1. International issues: OECD, EU and the US Tax Reform 1 04/07/2019 2 Main issues • Strong dematerialization of economies; DE lead to a new chain value • digital economy is essentially immaterial: firms have a huge capacity to supply digital good and services without physical nexus • key role of intangibles (patents, intellectual property, algorithms, etc.). Investments essentially in intangibles: macro and micro effects • DE is leading to a vanishing of tax bases? 2 Capitalism without Capital Haskel‐Westlake (2018) For centuries, when people wanted to measure the value of a firm, they counted and measured physical stuffs. Investments were all in tangible assets Digital firms: market value is a large multiple (40‐60?) of asset valuation from balance sheet. This is “Capitalism without capital” Investment in intangible are deeply different: effects on innovation & growth, productivity, inequality, financial policy, taxation Intangibles: a) presents sunk costs; b) generate spillovers; c) are more likely to be scalable (ex. brands, licensing agreements, etc.) d) synergies …. 2 04/07/2019 3 micro of multisided platforms P Tradizional One Side (pipeline) Market S • Elasticity D and S • Pricing • Market power and monopoly • Deadweight loss (inefficiency) D Q 3 Multisided Platforms • MPs create new (non‐existing) markets in many sectors, with two or more parts.