Cep68 and Cep215 (Cdk5rap2) Are Required for Centrosome Cohesion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mutations in CDK5RAP2 Cause Seckel Syndrome Go¨ Khan Yigit1,2,3,A, Karen E

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Mutations in CDK5RAP2 cause Seckel syndrome Go¨ khan Yigit1,2,3,a, Karen E. Brown4,a,Hu¨ lya Kayserili5, Esther Pohl1,2,3, Almuth Caliebe6, Diana Zahnleiter7, Elisabeth Rosser8, Nina Bo¨ gershausen1,2,3, Zehra Oya Uyguner5, Umut Altunoglu5, Gudrun Nu¨ rnberg2,3,9, Peter Nu¨ rnberg2,3,9, Anita Rauch10, Yun Li1,2,3, Christian Thomas Thiel7 & Bernd Wollnik1,2,3 1Institute of Human Genetics, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany 2Center for Molecular Medicine Cologne (CMMC), University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany 3Cologne Excellence Cluster on Cellular Stress Responses in Aging-Associated Diseases (CECAD), University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany 4Chromosome Biology Group, MRC Clinical Sciences Centre, Imperial College School of Medicine, Hammersmith Hospital, London, W12 0NN, UK 5Department of Medical Genetics, Istanbul Medical Faculty, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey 6Institute of Human Genetics, Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany 7Institute of Human Genetics, Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Erlangen, Germany 8Department of Clinical Genetics, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London, WC1N 3EH, UK 9Cologne Center for Genomics, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany 10Institute of Medical Genetics, University of Zurich, Schwerzenbach-Zurich, Switzerland Keywords Abstract CDK5RAP2, CEP215, microcephaly, primordial dwarfism, Seckel syndrome Seckel syndrome is a heterogeneous, autosomal recessive disorder marked by pre- natal proportionate short stature, severe microcephaly, intellectual disability, and Correspondence characteristic facial features. Here, we describe the novel homozygous splice-site Bernd Wollnik, Center for Molecular mutations c.383+1G>C and c.4005-9A>GinCDK5RAP2 in two consanguineous Medicine Cologne (CMMC) and Institute of families with Seckel syndrome. CDK5RAP2 (CEP215) encodes a centrosomal pro- Human Genetics, University of Cologne, tein which is known to be essential for centrosomal cohesion and proper spindle Kerpener Str. -

Supplemental Information Proximity Interactions Among Centrosome

Current Biology, Volume 24 Supplemental Information Proximity Interactions among Centrosome Components Identify Regulators of Centriole Duplication Elif Nur Firat-Karalar, Navin Rauniyar, John R. Yates III, and Tim Stearns Figure S1 A Myc Streptavidin -tubulin Merge Myc Streptavidin -tubulin Merge BirA*-PLK4 BirA*-CEP63 BirA*- CEP192 BirA*- CEP152 - BirA*-CCDC67 BirA* CEP152 CPAP BirA*- B C Streptavidin PCM1 Merge Myc-BirA* -CEP63 PCM1 -tubulin Merge BirA*- CEP63 DMSO - BirA* CEP63 nocodazole BirA*- CCDC67 Figure S2 A GFP – + – + GFP-CEP152 + – + – Myc-CDK5RAP2 + + + + (225 kDa) Myc-CDK5RAP2 (216 kDa) GFP-CEP152 (27 kDa) GFP Input (5%) IP: GFP B GFP-CEP152 truncation proteins Inputs (5%) IP: GFP kDa 1-7481-10441-1290218-1654749-16541045-16541-7481-10441-1290218-1654749-16541045-1654 250- Myc-CDK5RAP2 150- 150- 100- 75- GFP-CEP152 Figure S3 A B CEP63 – – + – – + GFP CCDC14 KIAA0753 Centrosome + – – + – – GFP-CCDC14 CEP152 binding binding binding targeting – + – – + – GFP-KIAA0753 GFP-KIAA0753 (140 kDa) 1-496 N M C 150- 100- GFP-CCDC14 (115 kDa) 1-424 N M – 136-496 M C – 50- CEP63 (63 kDa) 1-135 N – 37- GFP (27 kDa) 136-424 M – kDa 425-496 C – – Inputs (2%) IP: GFP C GFP-CEP63 truncation proteins D GFP-CEP63 truncation proteins Inputs (5%) IP: GFP Inputs (5%) IP: GFP kDa kDa 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl 1-135136-424425-4961-424136-496FL Ctl Myc- 150- Myc- 100- CCDC14 KIAA0753 100- 100- 75- 75- GFP- GFP- 50- CEP63 50- CEP63 37- 37- Figure S4 A siCtl -

Genetic and Genomic Analysis of Hyperlipidemia, Obesity and Diabetes Using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/Jngj) F2 Mice

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Nutrition Publications and Other Works Nutrition 12-19-2010 Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice Taryn P. Stewart Marshall University Hyoung Y. Kim University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Arnold M. Saxton University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Jung H. Kim Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_nutrpubs Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Nutrition Commons Recommended Citation BMC Genomics 2010, 11:713 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-713 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nutrition at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nutrition Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stewart et al. BMC Genomics 2010, 11:713 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/11/713 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice Taryn P Stewart1, Hyoung Yon Kim2, Arnold M Saxton3, Jung Han Kim1* Abstract Background: Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the most common form of diabetes in humans and is closely associated with dyslipidemia and obesity that magnifies the mortality and morbidity related to T2D. The genetic contribution to human T2D and related metabolic disorders is evident, and mostly follows polygenic inheritance. The TALLYHO/ JngJ (TH) mice are a polygenic model for T2D characterized by obesity, hyperinsulinemia, impaired glucose uptake and tolerance, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia. -

Autosomal Recessive Primary Microcephaly

Mahmood et al. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2011, 6:39 http://www.ojrd.com/content/6/1/39 REVIEW Open Access Autosomal recessive primary microcephaly (MCPH): clinical manifestations, genetic heterogeneity and mutation continuum Saqib Mahmood1, Wasim Ahmad2 and Muhammad J Hassan3* Abstract Autosomal Recessive Primary Microcephaly (MCPH) is a rare disorder of neurogenic mitosis characterized by reduced head circumference at birth with variable degree of mental retardation. In MCPH patients, brain size reduced to almost one-third of its original volume due to reduced number of generated cerebral cortical neurons during embryonic neurogensis. So far, seven genetic loci (MCPH1-7) for this condition have been mapped with seven corresponding genes (MCPH1, WDR62, CDK5RAP2, CEP152, ASPM, CENPJ, and STIL) identified from different world populations. Contribution of ASPM and WDR62 gene mutations in MCPH World wide is more than 50%. By and large, primary microcephaly patients are phenotypically indistinguishable, however, recent studies in patients with mutations in MCPH1, WDR62 and ASPM genes showed a broader clinical and/or cellular phenotype. It has been proposed that mutations in MCPH genes can cause the disease phenotype by disturbing: 1) orientation of mitotic spindles, 2) chromosome condensation mechanism during embryonic neurogenesis, 3) DNA damage- response signaling, 4) transcriptional regulations and microtubule dynamics, 5) certain unknown centrosomal mechanisms that control the number of neurons generated by neural precursor cells. Recent discoveries of mammalian models for MCPH have open up horizons for researchers to add more knowledge regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of MCPH. High incidence of MCPH in Pakistani population reflects the most probable involvement of consanguinity. -

An Extensive Program of Periodic Alternative Splicing Linked to Cell

RESEARCH ARTICLE An extensive program of periodic alternative splicing linked to cell cycle progression Daniel Dominguez1,2, Yi-Hsuan Tsai1,3, Robert Weatheritt4, Yang Wang1,2, Benjamin J Blencowe4*, Zefeng Wang1,5* 1Department of Pharmacology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, United States; 2Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, United States; 3Program in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, United States; 4Donnelly Centre and Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; 5Key Lab of Computational Biology, CAS-MPG Partner Institute for Computational Biology, Chinese Academy of Science, Shanghai, China Abstract Progression through the mitotic cell cycle requires periodic regulation of gene function at the levels of transcription, translation, protein-protein interactions, post-translational modification and degradation. However, the role of alternative splicing (AS) in the temporal control of cell cycle is not well understood. By sequencing the human transcriptome through two continuous cell cycles, we identify ~ 1300 genes with cell cycle-dependent AS changes. These genes are significantly enriched in functions linked to cell cycle control, yet they do not significantly overlap genes subject to periodic changes in steady-state transcript levels. Many of the periodically spliced genes are controlled by the SR protein kinase CLK1, whose level undergoes cell cycle- dependent fluctuations via an auto-inhibitory circuit. Disruption of CLK1 causes pleiotropic cell cycle defects and loss of proliferation, whereas CLK1 over-expression is associated with various *For correspondence: cancers. These results thus reveal a large program of CLK1-regulated periodic AS intimately [email protected] (BJB); associated with cell cycle control. -

Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly Primary Hereditary: an Overview

brain sciences Review Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly Primary Hereditary: An Overview Nikistratos Siskos † , Electra Stylianopoulou †, Georgios Skavdis and Maria E. Grigoriou * Department of Molecular Biology & Genetics, Democritus University of Thrace, 68100 Alexandroupolis, Greece; [email protected] (N.S.); [email protected] (E.S.); [email protected] (G.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] † Equal contribution. Abstract: MicroCephaly Primary Hereditary (MCPH) is a rare congenital neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a significant reduction of the occipitofrontal head circumference and mild to moderate mental disability. Patients have small brains, though with overall normal architecture; therefore, studying MCPH can reveal not only the pathological mechanisms leading to this condition, but also the mechanisms operating during normal development. MCPH is genetically heterogeneous, with 27 genes listed so far in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database. In this review, we discuss the role of MCPH proteins and delineate the molecular mechanisms and common pathways in which they participate. Keywords: microcephaly; MCPH; MCPH1–MCPH27; molecular genetics; cell cycle 1. Introduction Citation: Siskos, N.; Stylianopoulou, Microcephaly, from the Greek word µικρoκεϕαλi´α (mikrokephalia), meaning small E.; Skavdis, G.; Grigoriou, M.E. head, is a term used to describe a cranium with reduction of the occipitofrontal head circum- Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly ference equal, or more that teo standard deviations -

S41467-019-10037-Y.Pdf

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10037-y OPEN Feedback inhibition of cAMP effector signaling by a chaperone-assisted ubiquitin system Laura Rinaldi1, Rossella Delle Donne1, Bruno Catalanotti 2, Omar Torres-Quesada3, Florian Enzler3, Federica Moraca 4, Robert Nisticò5, Francesco Chiuso1, Sonia Piccinin5, Verena Bachmann3, Herbert H Lindner6, Corrado Garbi1, Antonella Scorziello7, Nicola Antonino Russo8, Matthis Synofzik9, Ulrich Stelzl 10, Lucio Annunziato11, Eduard Stefan 3 & Antonio Feliciello1 1234567890():,; Activation of G-protein coupled receptors elevates cAMP levels promoting dissociation of protein kinase A (PKA) holoenzymes and release of catalytic subunits (PKAc). This results in PKAc-mediated phosphorylation of compartmentalized substrates that control central aspects of cell physiology. The mechanism of PKAc activation and signaling have been largely characterized. However, the modes of PKAc inactivation by regulated proteolysis were unknown. Here, we identify a regulatory mechanism that precisely tunes PKAc stability and downstream signaling. Following agonist stimulation, the recruitment of the chaperone- bound E3 ligase CHIP promotes ubiquitylation and proteolysis of PKAc, thus attenuating cAMP signaling. Genetic inactivation of CHIP or pharmacological inhibition of HSP70 enhances PKAc signaling and sustains hippocampal long-term potentiation. Interestingly, primary fibroblasts from autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia 16 (SCAR16) patients carrying germline inactivating mutations of CHIP show a dramatic dysregulation of PKA signaling. This suggests the existence of a negative feedback mechanism for restricting hormonally controlled PKA activities. 1 Department of Molecular Medicine and Medical Biotechnologies, University Federico II, 80131 Naples, Italy. 2 Department of Pharmacy, University Federico II, 80131 Naples, Italy. 3 Institute of Biochemistry and Center for Molecular Biosciences, University of Innsbruck, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria. -

E-Mutpath: Computational Modelling Reveals the Functional Landscape of Genetic Mutations Rewiring Interactome Networks

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.22.262386; this version posted August 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. e-MutPath: Computational modelling reveals the functional landscape of genetic mutations rewiring interactome networks Yongsheng Li1, Daniel J. McGrail1, Brandon Burgman2,3, S. Stephen Yi2,3,4,5 and Nidhi Sahni1,6,7,8,* 1Department oF Systems Biology, The University oF Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA 2Department oF Oncology, Livestrong Cancer Institutes, Dell Medical School, The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 3Institute For Cellular and Molecular Biology (ICMB), The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 4Institute For Computational Engineering and Sciences (ICES), The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 5Department oF Biomedical Engineering, Cockrell School of Engineering, The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 6Department oF Epigenetics and Molecular Carcinogenesis, The University oF Texas MD Anderson Science Park, Smithville, TX 78957, USA 7Department oF BioinFormatics and Computational Biology, The University oF Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA 8Program in Quantitative and Computational Biosciences (QCB), Baylor College oF Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA *To whom correspondence should be addressed. Nidhi Sahni. Tel: +1 512 2379506; Email: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.22.262386; this version posted August 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

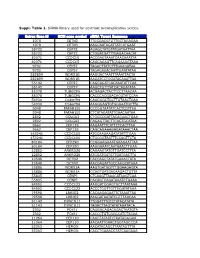

Suppl. Table 1

Suppl. Table 1. SiRNA library used for centriole overduplication screen. Entrez Gene Id NCBI gene symbol siRNA Target Sequence 1070 CETN3 TTGCGACGTGTTGCTAGAGAA 1070 CETN3 AAGCAATAGATTATCATGAAT 55722 CEP72 AGAGCTATGTATGATAATTAA 55722 CEP72 CTGGATGATTTGAGACAACAT 80071 CCDC15 ACCGAGTAAATCAACAAATTA 80071 CCDC15 CAGCAGAGTTCAGAAAGTAAA 9702 CEP57 TAGACTTATCTTTGAAGATAA 9702 CEP57 TAGAGAAACAATTGAATATAA 282809 WDR51B AAGGACTAATTTAAATTACTA 282809 WDR51B AAGATCCTGGATACAAATTAA 55142 CEP27 CAGCAGATCACAAATATTCAA 55142 CEP27 AAGCTGTTTATCACAGATATA 85378 TUBGCP6 ACGAGACTACTTCCTTAACAA 85378 TUBGCP6 CACCCACGGACACGTATCCAA 54930 C14orf94 CAGCGGCTGCTTGTAACTGAA 54930 C14orf94 AAGGGAGTGTGGAAATGCTTA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CCCGGTAATATCACTCGTTAA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CTCATAGATATTGAACAATAA 2802 GOLGA3 CTGGCCGATTACAGAACTGAA 2802 GOLGA3 CAGAGTTACTTCAGTGCATAA 9662 CEP135 AAGAATTTCATTCTCACTTAA 9662 CEP135 CAGCAGAAAGAGATAAACTAA 153241 CCDC100 ATGCAAGAAGATATATTTGAA 153241 CCDC100 CTGCGGTAATTTCCAGTTCTA 80184 CEP290 CCGGAAGAAATGAAGAATTAA 80184 CEP290 AAGGAAATCAATAAACTTGAA 22852 ANKRD26 CAGAAGTATGTTGATCCTTTA 22852 ANKRD26 ATGGATGATGTTGATGACTTA 10540 DCTN2 CACCAGCTATATGAAACTATA 10540 DCTN2 AACGAGATTGCCAAGCATAAA 25886 WDR51A AAGTGATGGTTTGGAAGAGTA 25886 WDR51A CCAGTGATGACAAGACTGTTA 55835 CENPJ CTCAAGTTAAACATAAGTCAA 55835 CENPJ CACAGTCAGATAAATCTGAAA 84902 CCDC123 AAGGATGGAGTGCTTAATAAA 84902 CCDC123 ACCCTGGTTGTTGGATATAAA 79598 LRRIQ2 CACAAGAGAATTCTAAATTAA 79598 LRRIQ2 AAGGATAATATCGTTTAACAA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TTGGATTTGTCTATACATATA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TAGACTTAGTATATAAATACA 2302 FOXJ1 CAGGACAGACAGACTAATGTA -

Association of Cnvs with Methylation Variation

www.nature.com/npjgenmed ARTICLE OPEN Association of CNVs with methylation variation Xinghua Shi1,8, Saranya Radhakrishnan2, Jia Wen1, Jin Yun Chen2, Junjie Chen1,8, Brianna Ashlyn Lam1, Ryan E. Mills 3, ✉ ✉ Barbara E. Stranger4, Charles Lee5,6,7 and Sunita R. Setlur 2 Germline copy number variants (CNVs) and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) form the basis of inter-individual genetic variation. Although the phenotypic effects of SNPs have been extensively investigated, the effects of CNVs is relatively less understood. To better characterize mechanisms by which CNVs affect cellular phenotype, we tested their association with variable CpG methylation in a genome-wide manner. Using paired CNV and methylation data from the 1000 genomes and HapMap projects, we identified genome-wide associations by methylation quantitative trait locus (mQTL) analysis. We found individual CNVs being associated with methylation of multiple CpGs and vice versa. CNV-associated methylation changes were correlated with gene expression. CNV-mQTLs were enriched for regulatory regions, transcription factor-binding sites (TFBSs), and were involved in long- range physical interactions with associated CpGs. Some CNV-mQTLs were associated with methylation of imprinted genes. Several CNV-mQTLs and/or associated genes were among those previously reported by genome-wide association studies (GWASs). We demonstrate that germline CNVs in the genome are associated with CpG methylation. Our findings suggest that structural variation together with methylation may affect cellular phenotype. npj Genomic Medicine (2020) 5:41 ; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-020-00145-w 1234567890():,; INTRODUCTION influence transcript regulation is DNA methylation, which involves The extent of genetic variation that exists in the human addition of a methyl group to cytosine residues within a CpG population is continually being characterized in efforts to identify dinucleotide. -

An Exome-Wide Sequencing Study of Lipid Response to High-Fat Meal and Fenofibrate in Caucasians from the GOLDN Cohort

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2018 An exome-wide sequencing study of lipid response to high-fat meal and fenofibrate in Caucasians from the GOLDN cohort Xin Geng Ping An Mary F. Feitosa Michael A. Province et al. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Supplemental Material can be found at: http://www.jlr.org/content/suppl/2018/02/20/jlr.P080333.DC1 .html patient-oriented and epidemiological research An exome-wide sequencing study of lipid response to high-fat meal and fenofibrate in Caucasians from the GOLDN cohort Xin Geng,* Marguerite R. Irvin,† Bertha Hidalgo,† Stella Aslibekyan,† Vinodh Srinivasasainagendra,§ Ping An,‡ Alexis C. Frazier-Wood,|| Hemant K. Tiwari,§ Tushar Dave,# Kathleen Ryan,# Jose M. Ordovas,$,**,†† Robert J. Straka,§§ Mary F. Feitosa,‡ Paul N. Hopkins,‡‡ Ingrid Borecki,|| || Michael A. Province,‡ Braxton D. Mitchell,# Donna K. Arnett,1,## and Degui Zhi1,*,$$ School of Biomedical Informatics* and School of Public Health,$$ The University of Texas Health Downloaded from Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030; Departments of Epidemiology† and Biostatistics,§ University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35233; Division of Statistical Genomics, Department of Genetics,‡ Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; US Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service Children’s Nutrition Research Center,|| Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030; Department of Medicine, Division -

CDK5RAP2 Functions in Centrosome to Spindle Pole Attachment and DNA Damage Response

JCB: Article CDK5RAP2 functions in centrosome to spindle pole attachment and DNA damage response Alexis R. Barr,1,2 John V. Kilmartin,3 and Fanni Gergely1,2 1Cancer Research UK Cambridge Research Institute, Cambridge CB2 0RE, England, UK 2Department of Oncology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3RA, England, UK 3Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge CB2 0QH, England, UK he centrosomal protein, CDK5RAP2, is mutated fail to recruit specific PCM components that mediate in primary microcephaly, a neurodevelopmental attachment to spindle poles. Furthermore, we show that Tdisorder characterized by reduced brain size. The the CNN1 domain enforces cohesion between parental Drosophila melanogaster homologue of CDK5RAP2, centrioles during interphase and promotes efficient DNA centrosomin (Cnn), maintains the pericentriolar matrix damage–induced G2 cell cycle arrest. Because mitotic (PCM) around centrioles during mitosis. In this study, we spindle positioning, asymmetric centrosome inheritance, demonstrate a similar role for CDK5RAP2 in vertebrate and DNA damage signaling have all been implicated cells. By disrupting two evolutionarily conserved domains in cell fate determination during neurogenesis, our find- of CDK5RAP2, CNN1 and CNN2, in the avian B cell line ings provide novel insight into how impaired CDK5RAP2 DT40, we find that both domains are essential for link- function could cause premature depletion of neural stem ing centrosomes to mitotic spindle poles. Although struc- cells and thereby microcephaly. turally intact, centrosomes lacking the CNN1 domain Introduction The centrosome consists of a pair of centrioles surrounded by 1995; Merdes et al., 1996, 2000; Gordon et al., 2001; Quintyne the pericentriolar matrix (PCM). In most animal cells, it is the and Schroer, 2002; Silk et al., 2009).