The Singular Plight of Sea-Borne Refugees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SENATE Official Hansard

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SENATE Official Hansard THURSDAY, 27 NOVEMBER 1997 THIRTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FIFTH PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE CANBERRA CONTENTS THURSDAY, 27 NOVEMBER Order of Business— Days and Hours of Sitting and Routine of Business ............. 9595 Leave of Absence ..................................... 9595 Native Title Amendment Bill 1997— Second Reading ...................................... 9595 Questions Without Notice— Native Title ......................................... 9644 Aboriginal Reconciliation ............................... 9646 Native Title ......................................... 9647 Arts Policy ......................................... 9648 Native Title ......................................... 9650 Native Title ......................................... 9652 Native Title ......................................... 9653 Greenhouse Gases .................................... 9653 Native Title ......................................... 9655 Mr Robert ‘Dolly’ Dunn ................................ 9656 Answers to Questions Without Notice— Taxation ........................................... 9657 Small Business ....................................... 9658 Fringe Benefits Tax ................................... 9658 Commonwealth Bank of Australia ......................... 9659 Current Account Data .................................. 9660 Travel Allowances .................................... 9660 Native Title ......................................... 9661 Petitions— Logging -

Lee Kuan Yew the Press Gallery�S Love Affair with Mr Keating Interviewed by Owen Harries Looks Like It�S Over

INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS LIMITED (Incorporated in the ACT) ISSN 1030 4177 IPA REVIEW Vol. 43 No. I June-August 1989 ki Productivity: the Prematurely r Counted Chicken John Brunner New figures show that plans for a national wage 2 IPA Indicators rise based on productivity gains are misplaced. In 30 years government expenditure per head in Australia has more than doubled. 13 Industrial Relations: the British Alternative 3 Editorials Joe Thompson The death throes of communism will be long and painful. Economic reform in Australia is moving The "British disease" has become a thing of the too slowly. Mr Keating on smaller government. past. Now Australia should take the cure. 8 - Press Index E Lee Kuan Yew The press gallerys love affair with Mr Keating Interviewed by Owen Harries looks like its over. Mr Macphee wins hearts, but Singapores experienced and astute PM on issues not where it counts. ranging from Gorbachev to regional trade. 11 Defending Australia 32 Myth and Reality in the Conservation Harry Gelber Debate The massacre in Beijing has burst the bubble of Ian Hore-Lacy illusion surrounding China. A cool assessment of the facts in an emotional debate. 16 Around the States Les McCaffrey 38 Big Governments Threat to the Rule If governments want investment they must stop of Law forever changing the rules. Denis White Youth Affairs How regulations can undermine the law. 25 Cliff Smith 48 Militarism and Ideology One hundred young Australians debate their Michael Walker countrys future. For Marxists in power the armed struggle continues. 26 Strange Times Ken Baker 50 Terms of Reference The Sex Pistols corrupted by capitalism; Billy John Nurick Bragg on being inspired by Leninism. -

MS 5110 National Aboriginal Conference, National Office And

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 5110 National Aboriginal Conference, National Office and Resource Centre records, 1974-1975, 1978-1985 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY .......…………………………………………………....…........ p.3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT ……………………………………........... p.3 ACCESS TO COLLECTION .………………………………...…….……………….......... p.4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW ………...……………………………………..…....…..…… p.5 ADMNISTRATIVE NOTE …............………………………………...…………........….. p.6 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... p.7 SERIES DESCRIPTION ………………………………………………………..……….... p.8 Series 1 NAC, National Executive, Meeting papers, 1974-1975, 1978-1985 p.8 Subseries 1/1 National Aboriginal Congress, copies of minutes of meetings and related papers, 1974-1975 ................................................ p.8 Subseries 1/2 National Aboriginal Conference, Minutes of meetings and related papers, 1979-1985 ......................................................... p.9 Subseries 1/3 National Aboriginal Conference, Resolutions and indexes to resolutions, 1978-1983 .............................................................. p.15 Subseries 1/4 Department of Aboriginal Affairs, Portfolio meeting papers, 1983-1984 .................................................................................. p.16 Series 2 NAC, National Office, Correspondence and telexes, 1979-1985.... p.20 Subseries 2/1 Correspondence registers, 1983-1985 ………………………… p.20 Subseries -

Australian Federation As Unfinished Business” Melbourne Journal of Politics 27: 47-67

The Constitution We Were Meant To Have Re-examining the origins and strength of Australia’s unitary political traditions Dr A J Brown Griffith University Senate Occasional Lecture Friday, 22 April 2005, 12.15pm–1.15pm Main Committee Room Parliament House, Canberra In 2005, New South Wales and Victoria celebrate the 150th anniversary of Australia’s first state constitutions. But despite their long history, how secure are the states in the culture and practice of Australian federalism? In another 150 years, will state governments exist as we know them today? In this paper Dr A J Brown reviews how Australia’s constitutional evolution has been strongly influenced by active and concrete ideas about a unitary constitutional system, beginning with under-recognised plans of the British Government dating from the late 1830s and repeated through a variety of home-grown proposals in most decades since. These traditions have a persistence which contemporary political science is often at a loss to explain, but which are here suggested to reflect a widely shared sense of a constitutional structure that Australia was ‘meant to have’, according to many citizens’ foundational political values, notwithstanding the specific twists and turns of postcolonial history. Alongside competing interpretations of federal values which have also been poorly understand, this vein of unitary political theory helps identify the extent to which Australian constitutional practice has become a mix of the worst of two traditions, rather than a balance or merging of their best elements as we might otherwise like to believe. Both the influence of unitary values, and their poorly reconciled relationship with federal principles continue to be strongly visible in contemporary politics, prompting the question whether or when we will again reinvest in an effective public discourse around the structural or territorial legitimacy of Australian federalism and intergovernmental relations. -

The Liberal Face of Liberalism

FEATURES 12 The Liberal Face o f LIBERALISM Dissatisfaction with 'economic rationalism' is not confined to the Left of the spectrum. Shaun Carney interviewed Jim Ritchie, the leading figure of a new Liberal breakaway group. im Ritchie is the spokesperson for Is it fair to characterise the Liberal Reform Movement as a revolt against economic rationalism? the Liberal Reform Movement, a group formed largely from disaf I think it's a response to the collapse of a number of fected members of the Victoria philosophical strains, rather than a revolt. In response to Liberal Party, many of whom were previously the Liberal Reform Movement I have had telephone calls supporters of state Liberal MP Ian Macphee. Its from former communists and arch conservatives, both complaining about the inadequacy of their former initial stated purpose is to campaign against philosophical positions, So it's not just about economic economic rationalism, the 'level playing field', rationalism, it's much broader than that. Perhaps i could and the Goods and Services Tax. Ritchie, 44, now put that into context. Let's take three strands of political a businessman, is a former ASIO officer and philosophy: Rousseau; John Locke; and socialism. Over the last decade, each of those three has been fundamentally Branch President of the Liberal Party, ALB : DECEMBER 1991 affected by changes in our society. The Rousseauian belief that a state of nature is an ideal, that nine-tenths of the worth of a particular thing is generated by nature and one-tenth by the ingenuity of man, has found its logical home in the environmental movement. -

SIQ 37 Vol 16.Qxd DON:7 29/7/10 11:50 AM Page 1

_7581 SIQ 37 Vol 16.qxd_DON:7 29/7/10 11:50 AM Page 1 ISSUE 37 JULY 2010 Memoirs and memory – GERARD HENDERSON on historical errors in the Simons- Fraser tome Helen Garner’s problem with fiction – PETER HAYES What’s happening to English - SHELLEY GARE on style and language STEPHEN MATCHETT and the Barack Obama (literary) industry ANNE HENDERSON searches for meaning from Christopher/Chris Hitchens ROSS FITZGERALD & STEPHEN HOLT – Doc Evatt revived JOHN MCCONNELL reviews the lives of Alan Reid and Nikki Savva PETE(R) STEEDMAN corresponds Vale JIM GRIFFIN MEDIA WATCH on leftist inner-city sandal wearers versus the people – Jon Faine, Brian Costar, Judith Brett, Catherine Deveny, Jill Singer, among others Published by The Sydney Institute 41 Phillip St. with Gerard Henderson’s Sydney 2000 Ph: (02) 9252 3366 MEDIA WATCH Fax: (02) 9252 3360 _7581 SIQ 37 Vol 16.qxd_DON:7 29/7/10 11:50 AM Page 2 The Sydney Institute Quarterly Issue 37, July 2010 CONTENTS MARK SCOTT - M.I.A. Soon after he was appointed managing director of the ABC in 2006, Mark Scott made a number of specific Editorial 2 commitments. He said he would ensure that the ABC presented a greater diversity of views on social and political Malcolm Fraser’s Memoirs - issues. He declared that the ABC TV Media Watch program The Fallibility of Memory would make it possible for those whom it criticised to have their views heard on the program itself. And he indicated - Gerard Henderson 3 that he would act in his position as ABC editor-in-chief in Adventures on the Road to Clarity addition to his role as ABC managing director. -

Submission to the Senate Environment, Communications, Information Technology 1 and the Arts References Committee

Friends of the ABC Submission to the Senate Environment, Communications, Information Technology 1 and the Arts References Committee National Spokesperson P.O. Box 547 Stepney, SA, 5069 Phone 08 8362 5183 Mobile 0412 684 178 Fax 08 8363 7548 Email [email protected] August 11, 2001 Ms Andrea Griffiths Secretary, Senate Environment, Communications, Information Technology and the Arts References Committee Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Ms Griffiths, Friends of the ABC Submission Thank you for allowing an extension of time for this submission. On behalf of Friends of the ABC I wish to make the following submission to the above committee in relation to: “The development and implementation of options for methods of appointment to the board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) that would enhance public confidence in the independence and the representativeness of the ABC as the national broadcaster" I will be available to appear before the committee if required. Friends of the ABC also seeks permission to publish this submission. Yours sincerely, Darce Cassidy National Spokesperson Friends of the ABC Friends of the ABC Submission to the Senate Environment, Communications, Information Technology 2 and the Arts References Committee CONTENTS • Executive Summary • Friends of the ABC • Nearly all agree that the current appointment process has been abused. • Politicisation of the ABC Bord is damaging because it threatens ABC independence , because it is destabilising, and because it erodes public trust in the ABC • Politicisation of boards damages government. • Politicisation of the ABC board threatens funding. • A more open system • Conclusion and recommendations. Appendix 1. The Composition and Character of the ABC's Governing Body, 1932-2001, by Professor Ken Inglis Appendix 2 Criticism of the Appointment Process by former Chairmen Appendix 3. -

ABC Annual Report 1997–1998

Australian Broadcasting Corporation annual report 1997–98 Australian Broadcasting Corporation annual report 1997–98 Australian Broadcasting Corporation annual report 1997–98 contents ABC Corporate Profile charter ABC Charter inside back cover Mission Statement 1 ABC Services 2 The functions and duties which Parliament has given to the ABC are set out in Significant Events 4 the Charter of the Corporation (ss6(1) and (2) of the Australian Broadcasting Priorities – Performance Summary 6 Corporation Act 1983). Financial Summary 10 6(1) The functions of the Corporation are — ABC Board Members 12 (a) to provide within Australia innovative and comprehensive broadcasting services of a ABC Organisation 14 high standard as part of the Australian broadcasting system consisting of national, Executive Members 15 commercial and community sectors and, without limiting the generality of the foregoing, to provide— Statement by Directors 16 (i) broadcasting programs that contribute to a sense of national identity and inform and entertain, and reflect the cultural diversity of, the Australian community; and Review of Operations (ii) broadcasting programs of an educational nature; Regional Services 21 (b) to transmit to countries outside Australia broadcasting programs of news, current Feature: Radio and Television Audiences 25 affairs, entertainment and cultural enrichment that will— National Networks 28 (i) encourage awareness of Australia and an international understanding of Australian News and Current Affairs 39 attitudes on world affairs; and Program Production 42 (ii) enable Australian citizens living or travelling outside Australia to obtain Enterprises 44 information about Australian affairs and Australian attitudes on world affairs; and Symphony Australia 47 (c) to encourage and promote the musical, dramatic and other performing arts in Human Resources 51 Australia. -

Queensland's Flying High Thinking About Justice for the Next Century What Shape Will We Be In? See P.29

Vol. 1 No. 9 November 1991 $4.00 Queensland's flying high Thinking about justice for the next century what shape will we be in? See p.29. Volume 1 Number 9 !ET November 199 1 A magazine of public affairs, the arts and theology CoNTENTS 4 23 COMMENT QUIXOTE 6 24 LETTERS THE PEOPLE NOBODY WANTS Damien Simonis reports on the Harkis, 7 France's unwanted legacy of the Algerian THE WITHERING OF THE HEATH war of independence. Peter Pierce takes the long view at Caulfield racecourse . 27 OBITUARY 8 Avery Dulles SJ pays tribute to French WORLD REPORT theologian Henri de Lubac SJ . Damien Simonis (p .S) and Liz Jackson (p.9) talk to Czechs and Russians about life after 28 the revolution. WHEN IS A RUIN REALLY A RUIN1 Mark Coleridge takes issue with Gerard 10 Windsor. DEMOCRACY ON THE BOIL Queensland may have something to teach 29 the southern states, concludes Margaret PAST IMPERFECT, Simons. FUTURE INDEFINITE Social justice for the next century. 15 ARCHIMEDES 36 BOOKS AND ARTS 16 Jack Waterford reviews Fred Hollow's CAPITAL LETTER autobiography; M.J. Crennan on Allister Sparks' and Rian Malan's views of South Cover design by John va n Loon; 17 Africa (p.39); Bmce Williams looks at the cartoons pp.6 and 45 THE EMPERORS WITHOUT CLOTHES work of Chamber Made Opera (p.42) . by Dean Moore; China's people are not fooled by their photOgraphs pp.5, 31, 33 and 35 by Andrew Stark. leaders, argues Paul Rule. 38 SPIRIT 19 Poem by Patrick O'Donoghue. -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1980 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-SECOND PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 25 NOVEMBER 1980 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the twenty-fifth day of November, in the twenty-ninth year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and eighty. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), John Athol Pettifer, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Douglas Maurice Blake, V.R.D., Deputy Clerk and Ian Charles Cochran, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION Commonwealth of Australia By His Excellency the Governor-General ZELMAN COWEN of the Commonwealth of.Australia Governor-General WHEREAS by section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is provided, amongst other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now THEREFORE I, Sir Zelman Cowen, the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, by this Proclamation appoint Tuesday, 25 November 1980 as the day for the Parliament of the Commonwealth to assemble for the despatch of business: And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly at Parliament House, Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory, at 11 o'clock in the morning on Tuesday, 25 November 1980. -

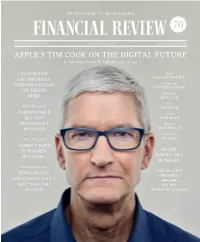

Apple's Tim Cook on the Digital Future

PLATINUM 70 MAGAZINE ANNIVERSARY COLLECTOR’S ISSUE AUGUST 20, 2021 SPECIAL EDITION APPLE’S TIM COOK ON THE DIGITAL FUTURE “Technology needs to rebuild your trust.” MACQUARIE Ivan CEO SHEMARA GLASENBERG WIKRAMANAYAKE Catherine LIVINGSTONE ON TAKING Michael RISKS HINTZE Jac John Howard NASSER COMFORTABLE Greg BUT NOT NORMAN NECESSARILY Robyn RELAXED DENHOLM Simone YOUNG Paul Keating “I DIDN’T HAVE TO HAPPEN. FRANK BUT I DID.” LOWY’S LIFE IN ISRAEL Baz Luhrmann ELVIS ON THE THE MODEST MEMBER GOLD COAST: CAN’T & HELP FALLING PIP PIP! IN LOVE PIERPONT’S BACK Turning points The moment everything changed ... ... and how it will change again. We asked 10 Australians, all of them global leaders in their fields, to tell us about a time that was transformative in their lives. We then asked for their prediction as to what might come next. Robyn The moment everything Hornsdale Power Reserve rivers and landfill with changed in South Australia, the those pollutants. Denholm The first is more personal, biggest battery in the Thinking specifically CHAIRMAN OF TESLA when I was moving to the world at the time, was a about Australia’s US from Sydney in August significant proof point opportunity, we’ve got 2001 with my two children. of battery storage as a an abundance of natural AS SPOKEN TO James Thomson, I was taking up the role firming technology for advantages of sunshine, Sally Patten, of VP of finance of the renewables by helping wind and hydro, and Jonathan Shapiro, global service business at the state to manage a dire we also have many of Philippa Coates AND Sun Microsystems. -

A Handbook of Australian Government and Politics 1965-1974 This Book Was Published by ANU Press Between 1965–1991

A Handbook of Australian Government and Politics 1965-1974 This book was published by ANU Press between 1965–1991. This republication is part of the digitisation project being carried out by Scholarly Information Services/Library and ANU Press. This project aims to make past scholarly works published by The Australian National University available to a global audience under its open-access policy. COLIN A. HUGHES A Handbook of Australian Government and Politics 1965-1974 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY PRESS CANBERRA 1977 First published in Australia 1977 Printed in Australia for the Australian National University Press, Canberra, at Griffin Press Limited, Netley, South Australia © Colin A. Hughes 1977 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Hughes, Colin Anfield. A handbook of Australian government and politics, 1965-1974. ISBN 0 7081 1340 0. 1. Australia—Politics and government—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title. 320.994 Southeast Asia: Angus & Robertson (S.E. Asia) Pty Ltd, Singapore Japan: United Publishers Services Ltd, Tokyo Acknowledgments This Handbook closely follows the model of its predecessor, A Handbook o f Australian Government and Politics 1890-1964, of which Professor Bruce Graham was co-editor, and my first debt is to him for the collaboration which laid down the ground rules. Mrs Geraldine Foley, who had been the principal research assistant for the original work, very kindly fitted in work on electoral data with her family responsibilities; once more her support has been invaluable.