The Liberal Forum, 1985–1987 (1987)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SENATE Official Hansard

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SENATE Official Hansard THURSDAY, 27 NOVEMBER 1997 THIRTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FIFTH PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE CANBERRA CONTENTS THURSDAY, 27 NOVEMBER Order of Business— Days and Hours of Sitting and Routine of Business ............. 9595 Leave of Absence ..................................... 9595 Native Title Amendment Bill 1997— Second Reading ...................................... 9595 Questions Without Notice— Native Title ......................................... 9644 Aboriginal Reconciliation ............................... 9646 Native Title ......................................... 9647 Arts Policy ......................................... 9648 Native Title ......................................... 9650 Native Title ......................................... 9652 Native Title ......................................... 9653 Greenhouse Gases .................................... 9653 Native Title ......................................... 9655 Mr Robert ‘Dolly’ Dunn ................................ 9656 Answers to Questions Without Notice— Taxation ........................................... 9657 Small Business ....................................... 9658 Fringe Benefits Tax ................................... 9658 Commonwealth Bank of Australia ......................... 9659 Current Account Data .................................. 9660 Travel Allowances .................................... 9660 Native Title ......................................... 9661 Petitions— Logging -

An Analysis of the Loss of HMAS SYDNEY

An analysis of the loss of HMAS SYDNEY By David Kennedy The 6,830-ton modified Leander class cruiser HMAS SYDNEY THE MAIN STORY The sinking of cruiser HMAS SYDNEY by disguised German raider KORMORAN, and the delayed search for all 645 crew who perished 70 years ago, can be attributed directly to the personal control by British wartime leader Winston Churchill of top-secret Enigma intelligence decodes and his individual power. As First Lord of the Admiralty, then Prime Minster, Churchill had been denying top secret intelligence information to commanders at sea, and excluding Australian prime ministers from knowledge of Ultra decodes of German Enigma signals long before SYDNEY II was sunk by KORMORAN, disguised as the Dutch STRAAT MALAKKA, off north-Western Australia on November 19, 1941. Ongoing research also reveals that a wide, hands-on, operation led secretly from London in late 1941, accounted for the ignorance, confusion, slow reactions in Australia and a delayed search for survivors . in stark contrast to Churchill's direct part in the destruction by SYDNEY I of the German cruiser EMDEN 25 years before. Churchill was at the helm of one of his special operations, to sweep from the oceans disguised German raiders, their supply ships, and also blockade runners bound for Germany from Japan, when SYDNEY II was lost only 19 days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Southeast Asia. Covering up of a blunder, or a punitive example to the new and distrusted Labor government of John Curtin gone terribly wrong because of a covert German weapon, can explain stern and brief official statements at the time and whitewashes now, with Germany and Japan solidly within Western alliances. -

Liberal Women: a Proud History

<insert section here> | 1 foreword The Liberal Party of Australia is the party of opportunity and choice for all Australians. From its inception in 1944, the Liberal Party has had a proud LIBERAL history of advancing opportunities for Australian women. It has done so from a strong philosophical tradition of respect for competence and WOMEN contribution, regardless of gender, religion or ethnicity. A PROUD HISTORY OF FIRSTS While other political parties have represented specific interests within the Australian community such as the trade union or environmental movements, the Liberal Party has always proudly demonstrated a broad and inclusive membership that has better understood the aspirations of contents all Australians and not least Australian women. The Liberal Party also has a long history of pre-selecting and Foreword by the Hon Kelly O’Dwyer MP ... 3 supporting women to serve in Parliament. Dame Enid Lyons, the first female member of the House of Representatives, a member of the Liberal Women: A Proud History ... 4 United Australia Party and then the Liberal Party, served Australia with exceptional competence during the Menzies years. She demonstrated The Early Liberal Movement ... 6 the passion, capability and drive that are characteristic of the strong The Liberal Party of Australia: Beginnings to 1996 ... 8 Liberal women who have helped shape our nation. Key Policy Achievements ... 10 As one of the many female Liberal parliamentarians, and one of the A Proud History of Firsts ... 11 thousands of female Liberal Party members across Australia, I am truly proud of our party’s history. I am proud to be a member of a party with a The Howard Years .. -

Lee Kuan Yew the Press Gallery�S Love Affair with Mr Keating Interviewed by Owen Harries Looks Like It�S Over

INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS LIMITED (Incorporated in the ACT) ISSN 1030 4177 IPA REVIEW Vol. 43 No. I June-August 1989 ki Productivity: the Prematurely r Counted Chicken John Brunner New figures show that plans for a national wage 2 IPA Indicators rise based on productivity gains are misplaced. In 30 years government expenditure per head in Australia has more than doubled. 13 Industrial Relations: the British Alternative 3 Editorials Joe Thompson The death throes of communism will be long and painful. Economic reform in Australia is moving The "British disease" has become a thing of the too slowly. Mr Keating on smaller government. past. Now Australia should take the cure. 8 - Press Index E Lee Kuan Yew The press gallerys love affair with Mr Keating Interviewed by Owen Harries looks like its over. Mr Macphee wins hearts, but Singapores experienced and astute PM on issues not where it counts. ranging from Gorbachev to regional trade. 11 Defending Australia 32 Myth and Reality in the Conservation Harry Gelber Debate The massacre in Beijing has burst the bubble of Ian Hore-Lacy illusion surrounding China. A cool assessment of the facts in an emotional debate. 16 Around the States Les McCaffrey 38 Big Governments Threat to the Rule If governments want investment they must stop of Law forever changing the rules. Denis White Youth Affairs How regulations can undermine the law. 25 Cliff Smith 48 Militarism and Ideology One hundred young Australians debate their Michael Walker countrys future. For Marxists in power the armed struggle continues. 26 Strange Times Ken Baker 50 Terms of Reference The Sex Pistols corrupted by capitalism; Billy John Nurick Bragg on being inspired by Leninism. -

MS 5110 National Aboriginal Conference, National Office And

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 5110 National Aboriginal Conference, National Office and Resource Centre records, 1974-1975, 1978-1985 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY .......…………………………………………………....…........ p.3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT ……………………………………........... p.3 ACCESS TO COLLECTION .………………………………...…….……………….......... p.4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW ………...……………………………………..…....…..…… p.5 ADMNISTRATIVE NOTE …............………………………………...…………........….. p.6 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... p.7 SERIES DESCRIPTION ………………………………………………………..……….... p.8 Series 1 NAC, National Executive, Meeting papers, 1974-1975, 1978-1985 p.8 Subseries 1/1 National Aboriginal Congress, copies of minutes of meetings and related papers, 1974-1975 ................................................ p.8 Subseries 1/2 National Aboriginal Conference, Minutes of meetings and related papers, 1979-1985 ......................................................... p.9 Subseries 1/3 National Aboriginal Conference, Resolutions and indexes to resolutions, 1978-1983 .............................................................. p.15 Subseries 1/4 Department of Aboriginal Affairs, Portfolio meeting papers, 1983-1984 .................................................................................. p.16 Series 2 NAC, National Office, Correspondence and telexes, 1979-1985.... p.20 Subseries 2/1 Correspondence registers, 1983-1985 ………………………… p.20 Subseries -

The Most Vitriolic Parliament

THE MOST VITRIOLIC PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE OF THE VITRIOLIC NATURE OF THE 43 RD PARLIAMENT AND POTENTIAL CAUSES Nicolas Adams, 321 382 For Master of Arts (Research), June 2016 The University of Melbourne, School of Social and Political Sciences Supervisors: Prof. John Murphy, Dr. Scott Brenton i Abstract It has been suggested that the period of the Gillard government was the most vitriolic in recent political history. This impression has been formed by many commentators and actors, however very little quantitative data exists which either confirms or disproves this theory. Utilising an analysis of standing orders within the House of Representatives it was found that a relatively fair case can be made that the 43rd parliament was more vitriolic than any in the preceding two decades. This period in the data, however, was trumped by the first year of the Abbott government. Along with this conclusion the data showed that the cause of the vitriol during this period could not be narrowed to one specific driver. It can be seen that issues such as the minority government, style of opposition, gender and even to a certain extent the speakership would have all contributed to any mutation of the tone of debate. ii Declaration I declare that this thesis contains only my original work towards my Masters of Arts (Research) except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text to other material used. Equally this thesis is fewer than the maximum word limit as approved by the Research Higher Degrees Committee. iii Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge my two supervisors, Prof. -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

Life Education NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report I Have Fond Memories of the Friendly, Knowledgeable Giraffe

Life Education NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report I have fond memories of the friendly, knowledgeable giraffe. Harold takes you on a magical journey exploring and learning about healthy eating, our body - how it works and ways we can be active in order to stay happy and healthy. It gives me such joy to see how excited my daughter is to visit Harold and know that it will be an experience that will stay with her too. Melanie, parent, Turramurra Public School What’s inside Who we are 03 Our year Life Education is the nation’s largest not-for-profit provider of childhood preventative drug and health education. For 06 Our programs almost 40 years, we have taken our mobile learning centres and famous mascot – ‘Healthy Harold’, the giraffe – to 13 Our community schools, teaching students about healthy choices in the areas of drugs and alcohol, cybersafety, nutrition, lifestyle 25 Our people and respectful relationships. 32 Our financials OUR MISSION Empowering our children and young people to make safer and healthier choices through education. OUR VISION Generations of healthy young Australians living to their full potential. LIFE EDUCATION NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report Our year: Thank you for being part of Life Education NSW Together we worked to empower more children in NSW As a charity, we’re grateful for the generous support of the NSW Ministry of Health, and the additional funds provided by our corporate and community partners and donors. We thank you for helping us to empower more children in NSW this year to make good life choices. -

Report No 3 the Use of “Henry VIII Clauses” in Queensland Legislation

The use of “Henry VIII Clauses” in Queensland Legislation Laid on the table and ordered to be printed. Scrutiny of Legislation Committee. LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF QUEENSLAND THE SCRUTINY OF LEGISLATION COMMITTEE THE USE OF “HENRY VIII CLAUSES” IN QUEENSLAND LEGISLATION JANUARY 1997 Scrutiny of Legislation Committee – Membership – 48th Parliament 2nd Session Chairman: Mr Tony Elliott MLA, Member for Cunningham Deputy Chairman: Mr Jon Sullivan MLA, Member for Caboolture Other Members: Mrs Liz Cunningham MLA, Member for Gladstone Hon Dean Wells MLA, Member for Murrumba1 Mr Neil Roberts MLA, Member for Nudgee Mr Frank Tanti MLA, Member for Mundingburra Legal Adviser To The Committee: Professor Charles Sampford Committee Staff: Ms Louisa Pink, Research Director Mr Simon Yick, Senior Research Officer Ms Cassandra Adams, Executive Assistant Ms Bronwyn Rout, Casual Administration Officer Scrutiny of Legislation Committee Level 6, Parliamentary Annexe George Street Brisbane QLD 4000 Phone: 07 3406 7671 Fax: 07 3406 7500 Email: [email protected] 1 Mr Paul Lucas MLA, Member for Lytton, replaced the Hon Dean Wells MLA, as a Member of the committee on 4 December 1996 Chairman’s Foreword Chairman’s Foreword For the past twenty-one years this Committee and its predecessor, the Subordinate Legislation Committee, have been making adverse reports to Parliament on provisions in legislation regarded as “Henry VIII clauses”. A “Henry VIII clause” is one which permits an Act of Parliament to be amended by subordinate legislation. However, no Parliamentary Committee in Queensland has, to date, conducted a detailed analysis of the use of such clauses. The Subordinate Legislation Committee resolved in 1995 to undertake such an examination. -

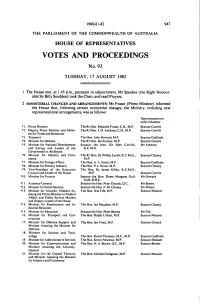

Votes and Proceedings

1980-81-82 947 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 93 TUESDAY, 17 AUGUST 1982 1 The House met, at 1.45 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. Mr Speaker (the Right Honour- able Sir Billy Snedden) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 MINISTERIAL CHANGES AND ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Fraser (Prime Minister) informed the House that, following certain ministerial changes, the Ministry, including new representational arrangements, was as follows: Representationin other Chamber *1. Prime Minister The Rt Hon. Malcolm Fraser, C.H., M.P. Senator Carrick *2. Deputy Prime Minister and Minis- The Rt Hon. J. D. Anthony, C.H., M.P. Senator Carrick ter for Trade and Resources *3. Treasurer The Hon. John Howard, M.P. Senator Guilfoyle *4. Minister for Defence The Rt Hon. lan Sinclair, M.P. Senator Durack *5. Minister for National Development Senator the Hon. Sir John Carrick, Mr Anthony and Energy and Leader of the K.C.M.G. Government in the Senate *6. Minister for Industry and Com- The Rt Hon. Sir Phillip Lynch, K.C.M.G., Senator Chaney merce M.P. *7. Minister for Foreign Affairs The Hon. A. A. Street, M.P. Senator Guilfoyle *8. Minister for Primary Industry The Hon. P. J. Nixon, M.P. Senator Chancy *9. Vice-President of the Executive The Hon. Sir James Killen, K.C.M.G., Council and Leader of the House M.P. Senator Carrick *10. Minister for Finance Senator the Hon. Dame Margaret Guil- Mr Howard foyle, D.B.E. *11. Attorney-General Senator the Hon. -

Australian Federation As Unfinished Business” Melbourne Journal of Politics 27: 47-67

The Constitution We Were Meant To Have Re-examining the origins and strength of Australia’s unitary political traditions Dr A J Brown Griffith University Senate Occasional Lecture Friday, 22 April 2005, 12.15pm–1.15pm Main Committee Room Parliament House, Canberra In 2005, New South Wales and Victoria celebrate the 150th anniversary of Australia’s first state constitutions. But despite their long history, how secure are the states in the culture and practice of Australian federalism? In another 150 years, will state governments exist as we know them today? In this paper Dr A J Brown reviews how Australia’s constitutional evolution has been strongly influenced by active and concrete ideas about a unitary constitutional system, beginning with under-recognised plans of the British Government dating from the late 1830s and repeated through a variety of home-grown proposals in most decades since. These traditions have a persistence which contemporary political science is often at a loss to explain, but which are here suggested to reflect a widely shared sense of a constitutional structure that Australia was ‘meant to have’, according to many citizens’ foundational political values, notwithstanding the specific twists and turns of postcolonial history. Alongside competing interpretations of federal values which have also been poorly understand, this vein of unitary political theory helps identify the extent to which Australian constitutional practice has become a mix of the worst of two traditions, rather than a balance or merging of their best elements as we might otherwise like to believe. Both the influence of unitary values, and their poorly reconciled relationship with federal principles continue to be strongly visible in contemporary politics, prompting the question whether or when we will again reinvest in an effective public discourse around the structural or territorial legitimacy of Australian federalism and intergovernmental relations. -

12 March 2021

10 000 COPIES/EDITION 12th - 26th March 2021 | Volume 38 – Issue 05 Local Stories, Local Events, Local People and Local Businesses A NEW LOOK FOR GATEWAY SUBURB FULL STORY ON PAGE 7 THE THE POSITIVE EARTHMOVING 4 Generations of Tree Experts - Over 60 years in the Industry. Knowledge and Expertise you can trust. THOUGHT ABOUT Rock Walls Built Tree Removal JOINING LIONS? All types of Excavations Pruning Stump Grinding Land Clearing Your Total Trade Solution for Castle Hill Lions warmly Mulch Sales Residential, Commercial & Industrial welcomes enquiries 0418 26 16 76 Firewood Sales Plumbing • Electrical • Hot Water [email protected] M: 0414 635 650 T: 9653 2205 Phone Philip - 0451 188 433 Est. Over 40 years [email protected] 0415 20 33 88 COMMUNITY NEWS From left: Bryan Mullan, Don Tait (Ex-Castle Hill RSL sub-Branch president), Oscar Henderson, Olivia Siloch, Castle Hill RSL sub-Branch president David Hand, Ellarose Halakas, Bethany Wade, Elizabeth Rodd (2019 Anzac Day Youth Ambassador) and Castle Hill RSL sub-Branch Vice-President Jim Wilson. Picture: Lawrence Machado ANZAC spirit will live forever by ELLAROSE HALAKAS As a secondary school Anzac Ambassador for Following the selection process of our school, 2021, it is an honour and privilege to reassure we were informed of the preparation which was the community and past veterans, that the necessary for the interview and key battles of the ANZAC Day Ambassadors, from left: Oscar Henderson, legacy of the Anzacs will remain eternal. Vietnam War which we would be assessed on. Olivia Siloch, Ellarose Halakas and Bethany Wade. I am a Year 11 student attending Marian We were interviewed by a panel, including in Vietnam has affected him,” Bethany said.