Criminal Records: the Relationship Between Music, Criminalisation and Harm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mike Mangini

/.%/&4(2%% 02):%3&2/- -".#0'(0%4$)3*4"%-&34&55*/(4*()54 7). 9!-!(!$25-3 VALUED ATOVER -ARCH 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 0/5)& '0$64)*)"5 "$)*&7&5)&$-"44*$ 48*/(406/% "35#-",&: 5)&.&/503 50%%46$)&3."/ 45:-&"/%"/"-:4*4 $2%!-4(%!4%23 Ê / Ê" Ê," Ê/"Ê"6 , /Ê-1 -- (3&(03:)65$)*/40/ 8)&3&+";;41"45"/%'6563&.&&5 #6*-%:06308/ .6-5*1&%"-4&561 -ODERN$RUMMERCOM 3&7*&8&% 5"."4*-7&345"33&.0108&34530,&130-6%8*("5-"4130)"3%8"3&3*.4)05-0$."55/0-"/$:.#"-4 Volume 36, Number 3 • Cover photo by Paul La Raia CONTENTS Paul La Raia Courtesy of Mapex 40 SETTING SIGHTS: CHRIS ADLER Lamb of God’s tireless sticksman embraces his natural lefty tendencies. by Ken Micallef Timothy Saccenti 54 MIKE MANGINI By creating layers of complex rhythms that complement Dream Theater’s epic arrangements, “the new guy” is ushering in a bold and exciting era for the band, its fans, and progressive rock music itself. by Mike Haid 44 GREGORY HUTCHINSON Hutch might just be the jazz drummer’s jazz drummer— historically astute and futuristically minded, with the kind 12 UPDATE of technique, soul, and sophistication that today’s most important artists treasure. • Manraze’s PAUL COOK by Ken Micallef • Jazz Vet JOEL TAYLOR • NRBQ’s CONRAD CHOUCROUN • Rebel Rocker HANK WILLIAMS III Chuck Parker 32 SHOP TALK Create a Stable Multi-Pedal Setup 36 PORTRAITS NYC Pocket Master TONY MASON 98 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT...? Faust’s WERNER “ZAPPI” DIERMAIER One of Three Incredible 70 INFLUENCES: ART BLAKEY Prizes From Yamaha Drums Enter to Win We all know those iconic black-and-white images: Blakey at the Valued $ kit, sweat beads on his forehead, a flash in the eyes, and that at Over 5,700 pg 85 mouth agape—sometimes with the tongue flat out—in pure elation. -

Indians in the American System: Past and Present, Student Book. the Lavinia and Charles P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 129 694 SO 009 474 AUTHOR Westbury, Ian; Westbury, Susan TITLE Indians in the American System: Past and Present, Student Book. The Lavinia and Charles P. Schwartz Citizenship Project. INSTITUTION Chicago Univ., Ill. Graduate School of Education. PUB nAT7 75 NOTE 80p.; For related documents, see SO 009 469-473 7,,DRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$4.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Culture; *American Indians; Anthropology; *Citizenship; Cultural Differences; Culture Conflict; Ethnic.Groups; Ethnic Stereotypes; Life Style; Pol'tical Science; Political Socialization; Reservations (Indian) ;Secondary Educa+ion; Social Studies; *United States History; War ABSTRACT The purpose of this curriculum unit on citizenship education is to enrich the way students think about AmericanIndians by presenting the history of American Indians and their relationship with white Americans. The first chapter discusses the kindsof ideas people have about Indians, especially stereotypes of Indians being wild, red-colored, and uncivilized. The second chapterlooks at the prehistory of Indian culture to see the ways in which Indianpeoples learned to exploit the land. The excavations ofan Indian camp site at Green Point, Michigan, are described, including discussionof the dig, findings, and changes in Indian life from S00-1700A.D. Chapter three recounts Indian-white relations during 1600-1900 inorder to explore what happened when a stone-age culture facedan acquisitive white culture that was more highly developed and hadmore resources. The Iroquois Indians in the northeastserve as an example of how Indian life patterns were destroyed by European, occupationof America. The last chapter examines the Indian-whitecontact and the way it has caused recent problems for Indians. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

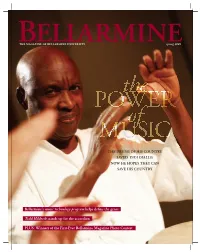

Bellarmine's Music Technology Program Helps Define the Genre Todd Hildreth Stands up for the Accordion PLUS

THE MAGAZINE OF BELLARMINE UNIVERSITY spring 2009 the POWER of MUSIC THE DRUMS OF HIS COUNTRY SAVED YAYA DIALLO; NOW HE HOPES THEY CAN SAVE HIS COUNTRY Bellarmine’s music technology program helps define the genre Todd Hildreth stands up for the accordion PLUS: Winners of the First-Ever Bellarmine Magazine Photo Contest 2 BELLARMINE MAGAZINE TABLE of CEONT NTS 5 FROM THE PRESIDENT Helping Bellarmine navigate tough times 6 THE READERS WRITE Letters to the editor 7 ‘SUITE FOR RED RIVER GORGE, PART ONE’ A poem by Lynnell Edwards 7 WHAT’S ON… The mind of Dr. Kathryn West 8 News on the Hill 14 FIRST-EVER BELLARMINE MAGAZINE PHOTO CONTEST The winners! 20 QUESTION & ANSWER Todd Hildreth has a squeezebox – and he’s not afraid to use it 22 DRUM CIRCLE Yaya Diallo’s music has taken him on an amazing journey 27 CONCORD CLASSIC This crazy thing called the Internet 28 BELLARMINE RADIO MAKES SOME NOISE Shaking up the lineup with more original programming 32 NEW HARMONY Fast-growing music technology program operates between composition and computers 34 CLASS NOTES 36 Alumni Corner 38 THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION COVER: DRUMMER YAYA DIALLO BRINGS THE HEALING ENERGY. —page 22 LEFT: FANS CHEER THE KNIGHTS TO ANOTHER VICTORY. COVER PHOTO BY GEOFF OLIVER BUGBEE PHOTO AT LEFT BY BRIAN TIRPAK spring 2009 3 from THE EDITOR Harmonic convergence OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY DR. JOSEPH J. MCGOWAN President WHB EN ELLARMINE MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTOR KATIE KELTY WENT TO The Concord archives in search of a flashback story for this issue’s “Concord Classic,” she DR. -

Of Contemporary Popular Music

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 11 Issue 2 Issue 2 - Winter 2009 Article 2 2009 The "Spiritual Temperature" of Contemporary Popular Music Tracy Reilly Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Tracy Reilly, The "Spiritual Temperature" of Contemporary Popular Music, 11 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 335 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol11/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The "Spiritual Temperature" of Contemporary Popular Music: An Alternative to the Legal Regulation of Death-Metal and Gangsta-Rap Lyrics Tracy Reilly* ABSTRACT The purpose of this Article is to contribute to the volume of legal scholarship that focuses on popular music lyrics and their effects on children. This interdisciplinary cross-section of law and culture has been analyzed by legal scholars, philosophers, and psychologists throughout history. This Article specifically focuses on the recent public uproar over the increasingly violent and lewd content of death- metal and gangsta-rap music and its alleged negative influence on children. Many legal scholars have written about how legal and political efforts throughout history to regulate contemporary genres of popular music in the name of the protection of children's morals and well-being have ultimately been foiled by the proper judicial application of solid First Amendment free-speech principles. -

Censorship in Popular Music Today and Its Influence and Effects on Adolescent Norms and Values Annotated Bibliography

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship Musicology and Ethnomusicology 11-2019 Censorship in Popular Music Today and Its Influence and ffE ects on Adolescent Norms and Values Sarah Wagner University of Denver, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Wagner, Sarah, "Censorship in Popular Music Today and Its Influence and ffE ects on Adolescent Norms and Values" (2019). Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship. 45. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/45 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Musicology and Ethnomusicology at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Censorship in Popular Music Today and Its Influence and ffE ects on Adolescent Norms and Values This bibliography is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student/45 Censorship in Popular Music Today and its Influence and Effects on Adolescent Norms and Values Annotated Bibliography Anthony, Kathleen S. “Censorship of Popular Music: An Analysis of Lyrical Content.” Masters research paper, Kent State University, 1995. ERIC Institute of Education Sciences. This particular study analyzes and compares the lyrics of popular music from 1986 through 1995, specifically music produced and created in the United States. The study’s purpose is to compare reasons of censorship within different genres of popular music such as punk, heavy metal and gangsta rap. -

Censorship of Popular Music: an Analysis of Lyrical Content. PUB DATE Jul 95 NOTE 38P.; Masters Research Paper, Kent State University

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 390 402 IR 055 749 AUTHOR Anthony, Kathleen S. TITLE Censorship of Popular Music: An Analysis of Lyrical Content. PUB DATE Jul 95 NOTE 38p.; Masters Research Paper, Kent State University. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Undetermined (040) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DELCRIPTORS Art; *Censorship; *Content Analysis; Moral Values; Obscenity; *Popular Music; Rock Music; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *Lyrics; Rap Music ABSTRACT This study analyzes the lyrical content of popular music recordings, cited as censored from 1986 through 1995, in order to examine chavacteristics of the recordings that were found to be objectionable and the frequency with which the objections occurred. Out of 60 articles from the music trade magazines, "Billboard" and "Rolling Stone," 77 instances of censorship were recorded and analyzed. The categories for evaluation were the year of citation, music style, and reason for censorship. Nineteen ninety was the year with the highest number of journal articles (21) covering music censorship. Rap (487.) and rock (44.27.) music accounted for a large portion of the total censored recordings and the majority of recordings were censored because of lyrics seen as explicit, profane, obscene or vulgar. In addition, five rock recordings were censored because of objectionable artwork on or inside the covers. Recordings were also censored because of opposition to a view the artist expressed. Two tables depict the years of citation and the reasons for censorship, each according to music styles. Appendices contain a list of the music censorship articles and a coding form for the year of citation, music style, and reason for censorship. -

The Spiritual Temperature of Contemporary Popular Music REILLY

The “Spiritual Temperature” of Contemporary Popular Music: An Alternative to the Legal Regulation of Death-Metal and Gangsta-Rap Lyrics Tracy Reilly* ABSTR ACT The purpose of this Article is to contribute to the volume of legal scholarship that focuses on popular music lyrics and their effects on children. This interdisciplinary cross-section of law and culture has been analyzed by legal scholars, philosophers, and psychologists throughout history. This Article specifically focuses on the recent public uproar over the increasingly violent and lewd content of death- metal and gangsta-rap music and its alleged negative influence on children. Many legal scholars have written about how legal and political efforts throughout history to regulate contemporary genres of popular music in the name of the protection of children’s morals and well-being have ultimately been foiled by the proper judicial application of solid First Amendment free-speech principles. Because the First Amendment prevents musicians from being held liable for their lyrics, and prevents the content of lyrics from being regulated, some scholars have suggested that the perceived problems with popular music lyrics could be dealt with by increasing public awareness and group action. * Assistant Professor of Law, University of Dayton School of Law, Program in Law & Technology, Dayton, Ohio. J.D., Valparaiso University School of Law, 1995; B.A., Northern Illinois University, 1990. The author would like to dedicate this Article to the loving memory of her first and best teacher, friend and mentor—her mother, Eileen Reilly. She would also like to thank her husband, Mark Budka, for his constant love and support; Kelly Henrici, Executive Director of the Program in Law & Technology, for her insightful comments and continuous encouragement; and Dean Lisa Kloppenberg and the University of Dayton School of Law for research support. -

Popular Music and Violence This Page Has Been Left Blank Intentionally Dark Side of the Tune: Popular Music and Violence

DARK SIDE OF THE TUNE: POPULAR MUSIC AND VIOLENCE This page has been left blank intentionally Dark Side of the Tune: Popular Music and Violence BRUCE JOHNSON University of Turku, Finland Macquarie University, Australia University of Glasgow, UK MARTIN CLOONAN University of Glasgow, UK © Bruce Johnson and Martin Cloonan 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Bruce Johnson and Martin Cloonan have asserted their moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington, VT 05401-4405 Surrey GU9 7PT USA England www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Johnson, Bruce, 1943– Dark side of the tune : popular music and violence. – (Ashgate popular and folk music series) 1. Music and violence 2. Popular music – Social aspects I. Title II. Cloonan, Martin 781.6'4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Johnson, Bruce, 1943– Dark side of the tune : popular music and violence / Bruce Johnson and Martin Cloonan. p. cm.—(Ashgate popular and folk music series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-7546-5872-6 (alk. paper) 1. Music and violence. 2. Popular music—Social aspects. I. Cloonan, Martin. II. Title. -

Le Droit À La Liberté D'expression Artistique Et De Création

Nations Unies A/HRC/23/34 Assemblée générale Distr. générale 14 mars 2013 Français Original: anglais Conseil des droits de l’homme Vingt-troisième session Point 3 de l’ordre du jour Promotion et protection de tous les droits de l’homme, civils, politiques, économiques, sociaux et culturels, y compris le droit au développement Rapport de la Rapporteuse spéciale dans le domaine des droits culturels, Mme Farida Shaheed Le droit à la liberté d’expression artistique et de création* Résumé La Rapporteuse spéciale dans le domaine des droits culturels, Mme Farida Shaheed, soumet le présent rapport en application de la résolution 19/6 du Conseil des droits de l’homme. Dans le présent rapport, la Rapporteuse spéciale examine les différentes manières dont le droit à la liberté indispensable à l’expression artistique et à la création peut être restreint. Elle se penche sur le constat croissant, dans le monde entier, que les voix artistiques ont été ou sont réduites au silence par des moyens divers et de différentes manières. Le rapport traite des lois et règlements qui restreignent les libertés artistiques ainsi que des questions économiques et financières qui ont une incidence considérable sur ces libertés. Les motivations profondes en sont le plus souvent politiques, religieuses, culturelles ou morales, ou reposent dans des intérêts économiques, ou sont une combinaison de ces éléments. La Rapporteuse spéciale encourage les États à un examen critique de leurs législations et pratiques qui imposent des restrictions au droit à la liberté d’expression artistique et de création, compte tenu de leurs obligations de respecter, protéger et réaliser ce droit.