Review of Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formative Years

CHAPTER 1 Formative Years Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a seaside town in western India. At that time, India was under the British raj (rule). The British presence in India dated from the early seventeenth century, when the English East India Company (EIC) first arrived there. India was then ruled by the Mughals, a Muslim dynasty governing India since 1526. By the end of the eighteenth century, the EIC had established itself as the paramount power in India, although the Mughals continued to be the official rulers. However, the EIC’s mismanagement of the Indian affairs and the corruption among its employees prompted the British crown to take over the rule of the Indian subcontinent in 1858. In that year the British also deposed Bahadur Shah, the last of the Mughal emperors, and by the Queen’s proclamation made Indians the subjects of the British monarch. Victoria, who was simply the Queen of England, was designated as the Empress of India at a durbar (royal court) held at Delhi in 1877. Viceroy, the crown’s representative in India, became the chief executive-in-charge, while a secretary of state for India, a member of the British cabinet, exercised control over Indian affairs. A separate office called the India Office, headed by the secretary of state, was created in London to exclusively oversee the Indian affairs, while the Colonial Office managed the rest of the British Empire. The British-Indian army was reorganized and control over India was established through direct or indirect rule. The territories ruled directly by the British came to be known as British India. -

Times-NIE-Web-Ed-AUGUST 14-2021-Page3.Qxd

CELLULAR JAIL, ANDAMAN & BIRLA HOUSE: Birla House is a muse- NICOBAR ISLANDS: Also known as um dedicated to Mahatma Gandhi. It ‘Kala Pani’, the British used the is the location where Gandhi spent CELEBRATING FREEDOM jail to exile political prisoners at the last 144 days of his life and was SATURDAY, AUGUST 14, 2021 03 this colonial prison assassinated on January 30, 1948 CLICK HERE: PAGE 3 AND 4 Pre-Independence slogans and its relevance in India today Slogans raised by leaders during the freedom movement set the mood of the nation’s revolution for its independence. They epitomised the struggle and hopes of millions of Indians. Author and former ad guru ANUJA CHAUHAN revisits these powerful slogans and explains their history and relevance in a contemporary India SATYAMEV JAYATE QUIT INDIA LIKE SWARAJ, KHADI IS (Truth alone triumphs) HISTORY: This slogan is widely associ- OUR BIRTH-RIGHT ated with Mahatma Gandhi (what he HISTORY: Inscribed at the base of started was the Quit India Movement India’s national emblem, this phrase is from August 8, 1942, in Bombay (then), a mantra from the ancient Indian scr- but the term ‘Quit India’ was actually ipture, ‘Mundaka Upanishad’, which coined by a lesser-known hero of was popularised by freedom fighter India’s freedom struggle – Yusuf Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya during Meherally. He had published a booklet India’s freedom movement. titled ‘Quit India’ (sold in weeks) and got over a thousand ‘Quit India’ badges to give life to the slogan that Gandhi also started using and popularised. ‘YOUNGSTERS, DON’T QUIT INDIA’: Quit India was a powerful slogan and HISTORY: Mahatma Gandhi’s call to as a slogan) was written by Urdu the jingle of an epic movement meant use khadi became a movement for poet Muhammad Iqbal in 1904 for to drive the British away from our the indigenous swadeshi (Indian) children. -

Raja Harishchandra Is a Most Thrilling Story from Indian Mythology. Harishchandra Was a Great King of India, Who Flourished Several Centuries Before the Christian Era

Notes The Times of India gave pre-screening publicity as follows: 'Raja Harishchandra is a most thrilling story from Indian mythology. Harishchandra was a great king of India, who flourished several centuries before the Christian era. He (sic) and his wife's names were household words in every Indian home for their truthfulness and chastity respectively. Their son Rohidas was a marvellous type of noble manhood. What Job was in Christian (sic) Bible, so Harischandra was in the Indian mythology. The patience of this king was tried so much that he was reduced to utter poverty and he had to pass his days in jungles in the company of cruel beasts. The same fate overcame his faithful wife and the dutiful son. But truth tri- umphed at last and they came out successfully through the ordeal. Several Indian scenes as depicted in this film are sim- ply marvellous. It is really a pleasure to see this piece of Indian workmanship'. The Bombay Chronicle, while reviewing Raja Harishchandra in its issue of Monday, 5th May 1913 said, 'An interesting de- parture is made this week by the management of Coronation Cinematographer. The first great Indian dramatic film on the lines of the great epics of the western world ... it is curious that the first experiment in this direction was so long in com- ing (sic) ... all the stories of Indian mythology era will long make their appearance ... followed by representations of modern dramas and comedies, another field which opens up vast possibilities ... it is to Mr Phalke that Bombay owes this .. -

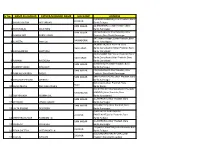

Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana-Gramin Block- M.Badshahpur

PRADHAN MANTRI AWAS YOJANA‐GRAMIN BLOCK‐ M.BADSHAHPUR Father Or Husband No of Registration #SNo Village Name Beneficiary Name Age Gender Category Remarks Name Member Status 1 Ahamadpur Gariyaon ANITA DEVI SUNIL KUMAR 26 Female Other 2 Completed 2 Ahamadpur Gariyaon ANITA DEVI VIDYA SAGAR 35 Female Other 2 Completed 3 Ahamadpur Gariyaon BELA DEVI SHIV NARESH 53 Female Other 2 Completed 4 Ahamadpur Gariyaon CHAD KUMARI SUSHIL KUMAR 29 Female Other 2 Completed 5 Ahamadpur Gariyaon CHHAYA DEVI CHHOTE LAL 28 Female Other 2 Completed 6 Ahamadpur Gariyaon KEVALA DEVI RAMRAJ 68 Female SC 2 Completed 7 Ahamadpur Gariyaon RAJ NARAYAN RAMSWARUP 58 Male SC 2 Completed 8 Ahamadpur Gariyaon SARADA DEVI 34 Female Other 2 Completed 9 Ahamadpur Gariyaon SITA VIJAY BAHADUR 33 Female Other 2 Completed 10 Ahamadpur Gariyaon SUNEETA KESARILAL 33 Female Other 2 Completed 11 Ahamadpur Gariyaon TASHVIRA DEVI RAMUJAGIR 48 Female Other 2 Completed 12 Ahamadpur Gariyaon 39 Female SC 3 Completed 1 Ahamadpur Kaithauli ANITA DEVI JAVAHIR 35 Female SC 1 Completed 2 Ahamadpur Kaithauli ASHA DEVI VINOD 22 Female Other 2 Completed 3 Ahamadpur Kaithauli DARM DEVI SURENDR PRATAP 33 Female Other 2 Completed 4 Ahamadpur Kaithauli GIRIJA SHANKAR SITA RAM 46 Male Other 1 Completed 5 Ahamadpur Kaithauli GUDDI RAJPATI 34 Female SC 2 Completed 6 Ahamadpur Kaithauli HIRAVATI PHULCHANDR 40 Female SC 1 Completed 7 Ahamadpur Kaithauli HIRAVATI RAJA RAM 62 Female Other 2 Completed 8 Ahamadpur Kaithauli KINTI DEVI RAMJATAN 58 Female SC 1 Completed 9 Ahamadpur Kaithauli KIRAN RAMSAKAL -

Sardar Patel University Vallabh Vidyanagar

SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY VALLABH VIDYANAGAR ELECTORAL ROLL OF COLLEGE TEACHERS / FACULTY TEACHERS JANUARY - 2018 SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY VALLABH VIDYANAGAR SENATE BY-ELECTION ELECTORAL ROLL OF COLLEGE TEACHERS / FACULTY TEACHERS – JANUARY 2018 (1) Faculties (under section-15 II (A) (i) : A FACULTY OF ARTS 1,2,3,7,8,9,11,17,21,22,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,45, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,56,57,58,69,75,76,77,79,80, 81,82,83,90,91,92,93,94,99,101,102,103,104,105, 113,114,115,122,123,124,125,127,128,129,131, 133,134 B FACULTY OF BUSINESS STUDIES 4,5,7,8,12,15,16,17,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,27,46, (COMMERCE) 58,59,71,72,74,75,76,77,90,95,98,99,103,105,110, 112,113,114,132,133 C FACULTY OF EDUCATION 4,5,6,26,31,46,47,50,74,75,79,82,101,109,110, 112,114,121,125 D FACULTY OF ENGINEERING & 28,29,78 TECHNOLOGY E FACULTY OF HOME SCIENCE 70,71,103,131,132 F FACULTY OF HOMOEOPATHY 6,95,96,97,98 G FACULTY OF LAW 9,10,46,69,89 H FACULTY OF MANAGEMENT 10,20,21,25,38,69,70,72,73,74,90,94,128,129 I FACULTY OF MEDICINE 27,28,29,30,38,39,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67, 68,69,89,90,105,106,108,109,111,112,115,121, 122 J FACULTY OF PHARMACEUTICAL 131 SCIENCE K FACULTY OF SCIENCE 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,18,19,22,24,32,33,34,35,36 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,52,53,54,55,56,57,59, 74,76,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,94,100, 101,103,104,106,107,108,110,112,116,117,118, 119,120,121,125,126,127,130,132,134,135,136, 137 (2) Colleges under Section-15 II (A) (ii) : COL. -

Gandhi and Tolstoy. a Study of Gandhi's Intellectual Development Considered Within the Framev,Ork of Hermeneutic Philosophy

Gandhi and Tolstoy. A study of Gandhi's Intellectual Development considered within the framev,ork of Hermeneutic Philosophy. GARTH ABRAHAM Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Natal, Durban. DECEMBER, 1982. PREFACE ii The intention of this dissertation is to assess the continuous and abiding influence of Tolstoy on Gandhi's intellectual development while in South Africa. With this objective in mind the hermeneutic philosophy of interpretation and understanding has been presented in the Introduction as a schema in terms of which Gandhi's intellectual development may be more readily understood. Hermeneutics attempts to expose the oft unrecognised fact that it is impossible to speak of 'presuppositionless' understanding It refutes the thesis that Gandhi's philosophy was either Hindu or Christian. Rather Gandhi's interpretation of Hinduism while in South Africa should be seen in terms of his familiarity with the 'Christian life-conception' of Tolstoy and the Theosophy of his London circle of acquaintances. As an attempt at an intellectual history it has also been necessary to relate Gandhi's development to historical reality in order to maintain some sort of chronological development in his thought. Furthermore certain key events in Gandhi's life have been discussed in some detail as they do to a considerable degree determine both the depth of his philosophy in terms of the manner in which he attempts to relate theory to praxis - and the direction his philosophy takes consequent to the event. With regard to source material for an intellectual history one has been forced to rely heavily on autobiographical material. -

Continuing Gandhi's Legacy of Cross-Cultural Understanding

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Title of Lesson: Continuing Gandhi’s Legacy of Cross-Cultural Understanding: Central Asia and the Middle East Lesson By: Susan Milan Grade Level/ Subject Areas: Class Size: Time/Duration of Lesson: K-3 Whole class 30 min. background on Could do literature circles Gandhi; subsequent 2-3+ with different books, with days, 30 minutes per book older kids reading to younger Guiding Questions: • How did Gandhi foster understanding between people from different cultures? • What do we share and how are we different from people in or from the Middle East and Central Asia (Pakistan and Afghanistan)? Lesson Abstract: This lesson will introduce Gandhi to children, focusing on his vision of unity and mutual respect. Students will develop awareness of children from Middle Eastern and Central Asian backgrounds through a variety of stories using authentic children’s literature. Students will notice and discuss similarities and differences between the story characters and themselves. Lesson Content: Mohandas Gandhi was a major influence on many people around the world, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He inspired people to choose nonviolence as a powerful tool to work for change. Gandhi was born in India on October 2, 1869. As a child, he learned meaningful lessons about truth and respecting others from his parents and a special story called Harishchandra , in which the main character is confronted with the challenge of telling the truth . These early experiences helped form his strong character and concern for others. When Gandhi was 19-years-old, he studied in England to become a lawyer, after which he went to work in South Africa. -

Sr No. NAME AS AADHAR FATHER/HUSBAND NAME ULB

Sr No. NAME AS AADHAR FATHER/HUSBAND NAME ULB NAME ADDRESS 0;AHIRAN ZAIDPUR;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara ZAIDPUR 1 VAIMUN NISHA MO SARVAR Banki;Zaidpur RAM NAGAR 20;KADIRABAD;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 2 KANDHAILAL SALIK RAM Banki;Ramnagar RAM NAGAR 157;BARABANKI RAM NAGAR;;Uttar 3 RAMSAHARE PARSHU RAM Pradesh ;Bara Banki;Ramnagar 347;Gandhi Nagar;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara NAWABGANJ 4 SUNEETA Prem Lal Banki;Nawabganj 14;MULIHA;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara DARIYABAD Banki;Dariyabad;0;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 5 SHIVSHANKAR SANTRAM Banki;Dariyabad 36;36;BANNE TALE;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara DARIYABAD Banki;Dariyabad;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 6 RAJRANI RAJENDRA Banki;Dariyabad RAM NAGAR 3;RAMNAGAR;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 7 RAMESH YADAV BHAGAUTI Banki;Ramnagar RAM NAGAR 209;BARABANKI RAM NAGAR;;Uttar 8 RAM JAS MAURYA BADLU Pradesh ;Bara Banki;Ramnagar RAM NAGAR 344/A;RAM NAGAR;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 9 BHAGAUTI PRASAD GHIRRAU Banki;Ramnagar 0;Nai basti;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara Banki 10 Ganga Mishra Ram Lalan Mishra Banki;Banki 0;BHEETRI PEERBATAWAN CHOTA JAIN NAWABGANJ MANDIR;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 11 OM PRAKASH MUNNA LAL Banki;Nawabganj RAM NAGAR 1;LAKHRORA;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 12 CHANDNI VINOD KUMAR Banki;Ramnagar RAM NAGAR 3;DHAMEDI 3;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 13 LALTA PRASAD DESI DEEN Banki;Ramnagar 0;MO. NAYA PURA NAGAR ZAIDPUR PANCHAYAT;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 14 VIRENDRA KUMAR BANWARI LAL Banki;Zaidpur RAM NAGAR 1;LAKHRORA;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 15 PHULENA GOURAKH Banki;Ramnagar 229;MOULVI KATRA;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara ZAIDPUR 16 BEWA SHEETLA LATE BARATI LAL Banki;Zaidpur 0;BUDHUGANJ NAYA PURA;;Uttar -

Urban Growth Analysis of Rajkot City Applying Remote-Sensing and Demographic Data

Urban Growth Analysis of Rajkot City Applying Remote-Sensing and Demographic Data Shaily Raju Gandhi* CEPT University, Ahmedabad Urban sprawl is one of the most avidly followed urban issues in India. The spatial and demographic processes of urban growth, and the societal implications along with cultural and financial aspects of economic development, need to be moni- tored closely while working on smart city projects. For decades, urban planners and governments aim at monitoring the dynamics of urban expansion. This paper applies a remote-sensing analysis of Rajkot, one of the fastest developing cities in India, during 1961-2011 and proposes a forecast for the development of the area by 2031. By doing that, the paper provides a methodology for the creation and the analysis of remote-sensing data in different wards and presents population scenarios for the city. Keywords: Urban Growth, Geographic Information System, Spatial, Temporal, Remote Sensing INTRODUCTION As more and more people leave their villages and farms to live in cities, urban growth extends the spatial and demographic process and urbanization takes place. In addition to the natural increase of population, the migration from neighboring towns and villages results in the increased importance of towns and cities as a con- centration of population within a particular economy and society (Clark, 1982). The rapid growth of cities strains their capacity to provide services such as social, economic and physical infrastructure (United Nations, 2005B). This is one of the many implications of urban development in the recent social and economic history. The broad view on urban sprawl and the related infrastructure systems is necessary to create a comprehensive analysis and understanding of urban sustainability and to facilitate better planning (Rahnama et.al., 2020). -

The Survival of Hindu Cremation Myths and Rituals

THE SURVIVAL OF HINDU CREMATION MYTHS AND RITUALS IN 21ST CENTURY PRACTICE: THREE CONTEMPORARY CASE STUDIES by Aditi G. Samarth APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Dr. Thomas Riccio, Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Richard Brettell, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Melia Belli-Bose ___________________________________________ Dr. David A. Patterson ___________________________________________ Dr. Mark Rosen Copyright 2018 Aditi G. Samarth All Rights Reserved Dedicated to my parents, Charu and Girish Samarth, my husband, Raj Shimpi, my sons, Rishi Shimpi and Rishabh Shimpi, and my beloved dogs, Chowder, Haiku, Happy, and Maya for their loving support. THE SURVIVAL OF HINDU CREMATION MYTHS AND RITUALS IN 21ST CENTURY PRACTICE: THREE CONTEMPORARY CASE STUDIES by ADITI G. SAMARTH, BFA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank members of Hindu communities across the globe, and specifically in Bali, Mauritius, and Dallas for sharing their knowledge of rituals and community. My deepest gratitude to Wayan at Villa Puri Ayu in Sanur, Bali, to Dr. Uma Bhowon and Professor Rajen Suntoo at the University of Mauritius, to Pandit Oumashanker, Pandita Barran, and Pandit Dhawdall in Mauritius, to Mr. Paresh Patel and Mr. Ashokbhai Patel at BAPS Temple in Irving, to Pandit Janakbhai Shukla and Pandit Harshvardhan Shukla at the DFW Hindu Ekta Mandir, and to Ms. Stephanie Hughes at Hughes Family Tribute Center in Dallas, for representing their varied communities in this scholarly endeavor, for lending voice to the Hindu community members they interface with in their personal, professional, and social spheres, and for enabling my research and documentation during a vulnerable rite of passage. -

My Experiments with Truth 4 by M.K

My Experiments with Truth 4 by M.K. Gandhi Pre-reading Task To err is human. All human beings make mistakes. But the best of the lot learn from their mistakes and improve. 1. Have you ever made any mistake? 2. What did you learn from it? 3. What do you do when you fi nd a drawback or weakness— (i) try to improve yourself? (ii) try to forget it and don’t care at all? (iii) try to hide it from others? (iv) try to lay the blame on others? Now read this extract from Gandhiji’s autobiography My Experiments with Truth. I must have been about seven when I was put into a primary school and I can well recollect those days, including the names and other particulars of the teachers who taught me. I do not remember having ever told a lie, either to my teachers or to my schoolmates. I used to be very shy and avoided all company. My books and my lessons were my sole companions. To be at school at the stroke of the hour and to run back home as soon as the school closed—that was my daily habit. Two incidents belonging to this period have always clung to my memory. As a rule, I had a distaste for any reading beyond my school books but somehow my eyes fell on a book purchased by my father. It was Shravana Pitribhakti Nataka (a play about Shravana’s devotion to his parents). I read it with intense interest. One picture in the book showed Shravana carrying his parents on clung: held on closely intense: deep 20 Ch04new.indd 20 11/27/2015 6:36:01 AM pilgrimage. -

Q. 1. When Was Gandhiji Born? (A) 2Nd October, 1868 (B) 2Nd October, 1869 (C) 2Nd October, 1870 (D) 2Nd October, 1871 Ans : (B) 2Nd October, 1869

Q. 1. When was Gandhiji born? (a) 2nd October, 1868 (b) 2nd October, 1869 (c) 2nd October, 1870 (d) 2nd October, 1871 Ans : (b) 2nd October, 1869 Q. 2. By which name is Gandhiji’s ancestral home known today? (a) Birla House (b) Gandhi Nagar (c) Bankanair’s House (d) Kirti Mandir Ans : (d) Kirti Mandir Q. 3. Where did Gandhiji receive his primary education? (a) Sudamapuri (b) Bikaner (c) Porbandar (d) Rajkot Ans : (d) Rajkot Q. 4. Which of these activities did Gandhiji like since childhood? (a) Yoga (b) Kite flying (c) Wrestling (d) Walking Ans : (d) Walking Q. 5. Which mythological character impressed Gandhiji for life when he saw a play on his life? (a) Harishchandra (b) Ashoka (c) Vikramaditya (d) Krishna Ans : (a) Harishchandra Q. 6. Which Indian acquaintance was Gandhiji’s companion on his first overseas journey? (a) Mavji Dave (b) Thatcherji Swami (c) Raichand Bhai (d) Lawyer Sh. Trayambakrao Majumdar Ans : (d) Lawyer Sh. Trayambakrao Majumdar Q. 7. Which book influenced Gandhiji greatly, which he read in England? (a) Be Vegetarian (b) Vegetables are good for health (c) Plea for vegetarianism (d) Use vegetables Ans : (c) Plea for vegetarianism Q. 8. Whose English translation of Gita influenced Gandhiji? (a) Ruskin (b) Edwin Arnold (c) Tolstoy (d) Mr. Baker Ans : (b) Edwin Arnold Q. 9. Which book inspired him towards spiritualism? (a) Theosophy-Rahasya (b) Unto the last (c) The Kingdom of God is within you (d) Buddha Chaitra Ans : (a) Theosophy-Rahasya Q. 10. Whose books inspired Gandhiji towards truth and justice? (a) Ruskin (b) Tolstoy (c) Mr.