PM#0001161822 Editorial Board Comité De Rédaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magazine of Aecon Group Winter 2015, Volume 2, Issue 4

THE MAGAZINE OF AECON GROUP WINTER 2015, VOLUME 2, ISSUE 4 IN THIS ISSUE: ALL ABOARD THE UP EXPRESS CLOSE QUARTERS A DEFINING RELATIONSHIP CONNECTING TO OPPORTUNITY Union Pearson Express Enbridge South Edmonton Highway 407 Interchange Neskantaga Training Centre Terminal ı (Tı) Station Terminal Tank Farm and Brock Road Realignment Expansion PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #41329046 THE MAGAZINE OF AECON GROUP WINTER 2015, VOLUME 2, ISSUE 4 4 24 34 50 ALL ABOARD CLOSE QUARTERS A DEFINING RELATIONSHIP CONNECTING TO THE UP EXPRESS Enbridge South Highway 407 OPPORTUNITY Union Pearson Express Edmonton Terminal Interchange and Brock Neskantaga Terminal ı (Tı) Station Tank Farm Expansion Road Realignment Training Centre IN THIS ISSUE: 2 Living Our Core Values of Trust, Excellence and a Learning Culture By Teri McKibbon 4 All Aboard the UP Express Union Pearson Express Terminal 1 (T1) Station 18 Did You Know? Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line 24 Close Quarters Enbridge South Edmonton Terminal Tank Farm Expansion 30 Meet Carlos Travassos 34 A Defining Relationship Highway 407 Interchange and Brock Road Realignment 46 Meet Brandon Alpine 50 Connecting to Opportunity Neskantaga Training Centre 58 The Aecon Safety Opportunity Program By Mike Archambault COVER: UP EXPRESS TERMINAL 1 STATION, TORONTO, ONTARIO LEFT: AECON’S VISION: 407 EXTENSION, PICKERING, ONTARIO To be the first company people go to for building things that matter. ABOVE: ENBRIDGE SOUTH EDMONTON TANK FARM, EDMONTON, ALBERTA ONE is a magazine published by Aecon Michele Walter, Editor-in-Chief BACK COVER: Group Inc. for its employees and clients. Matthew Le Blanc, Features Editor GIRDER WORK AT 407 ETR, PICKERING, ONTARIO For more information about Aecon, visit Rick Radell, Photographer This magazine includes certain forward-looking statements our website at aecon.com. -

Annual Information Form

407 INTERNATIONAL INC. Annual Information Form For the Year Ended December 31, 2020 As at February 11, 2021 ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS ............................................................................................... 5 CORPORATE STRUCTURE ............................................................................................................... 5 1. Name, Address, Incorporation and Ownership ................................................................. 5 2. Intercorporate Relationships ................................................................................................. 5 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF BUSINESS .................................................................................... 6 1. Traffic ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Construction ............................................................................................................................. 6 3. Information Technology ......................................................................................................... 7 4. Customer Service .................................................................................................................... 7 5. Other Developments ............................................................................................................... 8 5.1. International Organization for Standardization (“ISO”) .......................................................... -

Annual Information Form

407 INTERNATIONAL INC. Annual Information Form For the Year Ended December 31, 2017 As at February 15, 2018 ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS ............................................................................................... 5 CORPORATE STRUCTURE ............................................................................................................... 5 1. Name, Address, Incorporation and Ownership ................................................................. 5 2. Intercorporate Relationships ................................................................................................ 5 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF BUSINESS .................................................................................... 6 1. Traffic ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Construction ............................................................................................................................. 6 3. Information Technology ......................................................................................................... 7 4. Customer Service .................................................................................................................... 7 5. Other Developments ............................................................................................................... 8 5.1. International Organization for Standardization (“ISO”) .......................................................... -

Annual Information Form

407 INTERNATIONAL INC. Annual Information Form For the Year Ended December 31, 2019 As at February 19, 2020 ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS ............................................................................................... 5 CORPORATE STRUCTURE ............................................................................................................... 5 1. Name, Address, Incorporation and Ownership ................................................................. 5 2. Intercorporate Relationships ................................................................................................ 5 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF BUSINESS .................................................................................... 6 1. Traffic ......................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Construction ............................................................................................................................. 6 3. Information Technology ......................................................................................................... 6 4. Customer Service .................................................................................................................... 7 5. Other Developments ............................................................................................................... 7 5.1. International Organization for Standardization (“ISO”) .......................................................... -

Operations Committee Minutes May 29, 2017 -7:00 Pm Council Chambers Whitby Municipal Building

Operations Committee Minutes May 29, 2017 -7:00 pm Council Chambers Whitby Municipal Building Present: Mayor Mitchell Councillor Emm Councillor Gleed Councillor Leahy Councillor Mulcahy Also Present: Councillor Drumm (left the meeting at 9:01 p.m.) Councillor Roy Councillor Yamada M. Gaskell, Chief Administrative Officer S. Beale, Commissioner of Public Works P. LeBel, Commissioner of Community & Marketing Services W. Mar, Commissioner of Legal and By-law Services/Town Solicitor K. Nix, Commissioner of Corporate Services/Treasurer R. Short, Commissioner of Planning C. Siopis, Manager of Corporate Communications D. Speed, Fire Chief S. Cassel, Deputy Clerk L. MacDougall, Council and Committee Coordinator (Recording Secretary) Regrets: None noted 1. Declarations of Pecuniary Interest 1.1 Councillor Leahy made a declaration of pecuniary interest under the Municipal Conflict of Interest Act with respect to Item 6.12, FR 07-17 regarding Accessory Apartments - Education and Regulatory Options, as he is in the process of constructing an accessory apartment. Councillor Leahy did not take part in the discussion or voting on this matter. 2. Presentations 2.1 There were no presentations. Page 1 of 22 Operations Committee Minutes May 29, 2017 - 7:00 PM 3. Delegations 3.1 There were no delegations. 4. Correspondence 4.1 There was no correspondence. 5. Public Meetings 5.1 There were no public meetings. 6. Staff Reports 6.1 Corporate Services Department and Public Works Department Joint Report, CS 44-17 Re: Replacement of Chain Link Fence (T-573-2017) Recommendation: Moved By Councillor Gleed 1. That the Town of Whitby accept the low tender of C&C Built Right Ltd. -

Financial and Technical Feasibility of Dynamic Congestion Pricing As A

MN WI MI OH IL IN USDOT Region V Regional University Transportation Center Final Report NEXTRANS Project No 044PY02 Financial and Technical Feasibility of Dynamic Congestion Pricing as a Revenue Generation Source in Indiana – Exploiting the Availability of Real-Time Information and Dynamic Pricing Technologies By Apichai Issariyanukula Graduate Student School of Civil Engineering Purdue University [email protected] and Samuel Labi, Principal Investigator Assistant Professor School of Civil Engineering Purdue University [email protected] Report Submission Date: October 19, 2011 DISCLAIMER Funding for this research was provided by the NEXTRANS Center, Purdue University under Grant No. DTRT07-G-005 of the U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and Innovative Technology Administration (RITA), University Transportation Centers Program. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation, University Transportation Centers Program, in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. MN WI MI OH IL IN USDOT Region V Regional University Transportation Center Final Report TECHNICAL SUMMARY NEXTRANS Project No 044PY02 Final Report, October 19 Financial and Technical Feasibility of Dynamic Congestion Pricing as a Revenue Generation Source in Indiana – Exploiting the Availability of Real-Time Information and Dynamic Pricing Technologies Introduction Highway stakeholders continue to support research studies that address critical issues of the current era, including congestion mitigation and revenue generation. A mechanism that addresses both concerns is congestion pricing which establishes a direct out-of-pocket charge to road users thus potentially generating revenue and also reducing demand during peak hours. -

Erlene Brown & Rosa Macleod

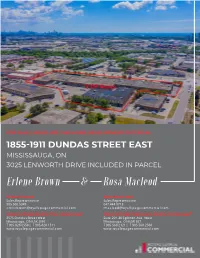

FOR SALE | MIXED USE / HIGH RISE DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL 1855-1911 DUNDAS STREET EAST MISSISSAUGA, ON 3025 LENWORTH DRIVE INCLUDED IN PARCEL Erlene Brown & Rosa Macleod Erlene Brown Rosa MacLeod Sales Representative Sales Representative 905.580.5349 647.444.9715 [email protected] [email protected] Royal LePage Realty Plus, Brokerage* Royal LePage Signature Realty, Brokerage* 2575 Dundas Street West Suite 201-30 Eglinton Ave. West Mississauga, ON L5K 2M6 Mississauga, ON L5R 3E7 T 905.828.6550 | F 905.828.1511 T 905.568.2121 | F 905.568.2588 www.royallepagecommercial.com www.royallepagecommercial.com THE OFFERING HIGHLIGHTS Royal LePage Commercial is pleased to offer for sale 1855-1911 Dundas Street East (the “Property” or PROFESSIONALLY MANAGED “Site”), a landmark investment opportunity located on Ontario’s major arterial road, Dundas Street East in PROPERTY Mississauga. This 7.09 Acre site has 819’ frontage on Dundas and is located within the Mississauga “Dundas Capital spending on the existing building which Connects” Master Plan and Ontario’s “A Place to includes roof replacement completed in July Grow: Growth Plan” act. It is ideal for mixed-use/ 2020 plus several tenant improvements high rise development that can provide for the future residents of this growing city. Mississauga, Canada’s 6th largest city and third-most GREAT INVESTMENT TO HOLD AND in Ontario is known for its suburban living with urban DEVELOP conveniences. Sought after location by immigrants from all over the world, Mississauga has seen a lot of Currently the buildings on the site are 100 % investment flowing in to build condos, residential and Leased. -

September 1, 2011

clrY couNqL Laura Olhasso, Mayor Donald R. Voss, Mayor Pro Tem ii Gregory C. Brown Slephen A. Del Guercio David A. Spence Funrruocn Mr. Mike Jones Regional Planner Southem California Association of Governments 818 W, 7h Street, 12ù Floor I-os Angeles, CA 90017-3435 SUBJECT: ul-710 Missing Link Truck Study" Comments Dear Mr. Jones: Backeround: The City of La Cañada Flintridge has reviewed the Draft Final Report for the I-7I0 Missing I ink Truck Study prepared by Iteris dated lNlay 2009. In addition, City staff has participated in several meetings hosted by the Arroyo-Verdugo Subregion regarding this Study. This Study was commissioned by the Southern Califomia Association of Governments (SCAG) to further exnmine the poûential vehicle and tn¡ck impacts on the surrounding freeway and roadway network if a tunnel was constn¡cted between the existing northerþterminus of the SR-710 FreewayinAlhambra andthe I-210ISR- 1 34 frceway interchange in Pasadena. SCAG has emphasized that this study is technical and comparative in nature and is not meant as a recommendation either for or against a freeway tunnel. Citv Comments: The City's primary objections are the assumptions made in the preparation of the Study and unilateral recommendations of its conclusion. We question the usefulness and inænt of the Study's findings, and are concemed about the myopic analysis made without consideration of the larger context of the alternatives and effects on regional traff,rc. But most importantly, the City also questions the usefulness of constructing the tunnel, since, based on the study's findings, if the In response to SCAG's request for comments on the draft Final Report, the following detailed comments have been prepared after a review of the Study and listening to the technical consultant presentations. -

Enhancing Transportation Corridors to Support Southern Ontario Innovation Ecosystems

Enhancing Transportation Corridors to Support Southern Ontario Innovation Ecosystems May 10, 2016 Enhancing Transportation Corridors To Support Southern Ontario Innovation Ecosystems Mark Ferguson Carly Harrison Joelle Pang Chris Higgins Pavlos Kanaroglou McMaster Institute for Transportation and Logistics McMaster University Hamilton, Ontario May 10, 2016 mitl.mcmaster.ca Enhancing Innovation Corridors in Southern Ontario Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... v 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ................................................................................ 8 1.1 Rationale and Objectives ..........................................................................................................8 1.2 An Overview of Innovation Clusters ..........................................................................................9 1.3 Innovation Clusters and Transportation ................................................................................... 11 1.4 Transportation Improvements and Economic Development Impacts ........................................ 11 1.5 The Importance of Transportation Corridors ............................................................................ 12 1.6 Commuting Behaviour and “Super-Commuting” ...................................................................... 13 1.7 Comparisons of Freight and Rail between North America and Europe ...................................... 15 1.8 Scope -

Public-Private Partnership (P3) Procurement: a Guide for Public Owners

Public-Private Partnership (P3) Procurement: A Guide for Public Owners March 2019 Public-Private Partnership Procurement Guide Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of information contained in this document. The U.S. Government does not endorse products of manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Quality Assurance Statement The U.S. Department of Transportation (U.S. DOT) provides high quality information to serve Government, industry, and the public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. U.S. DOT periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement. Public-Private Partnership Procurement Guide Form DOT F 1700. 7 (8-72) 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-HIN-18-004 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date March 2019 Public-Private Partnership (P3) Procurement: A Guide for Public Owners 6. Performing Organization Code FHWA 7. Authors 8. Performing Organization Nancy Smith, Patricia de la Peña, Edward Kussy (Nossaman LLP), Sonika Sethi Report No. -

Pricing Traffic Congestion Report

WE CAN’T GET THERE FROM HERE: WHY PRICING TRAFFIC CONGESTION IS CRITICAL TO BEATING IT NOVEMBER 2015 CANADA’S ECOFISCAL COMMISSION WHO WE ARE A group of independent, policy-minded Canadian economists working together to align Canada’s economic and environmental aspirations. We believe this is both possible and critical for our country’s continuing prosperity. Our Advisory Board comprises prominent Canadian leaders from across the political spectrum. We represent different regions, philosophies, and perspectives from across the country. But on this we agree: ecofiscal solutions are essential to Canada’s future. OUR VISION OUR MISSION A thriving economy underpinned by clean To identify and promote practical fiscal air, land, and water for the benefit of all solutions for Canada that spark the innovation Canadians, now and in the future. required for increased economic and environmental prosperity. For more information about the Commission, visit Ecofiscal.ca WE CAN’T GET THERE FROM HERE II A REPORT AUTHORED BY CANADA’S ECOFISCAL COMMISSION Chris Ragan, Chair Bev Dahlby Paul Lanoie McGill University University of Calgary HEC Montréal Elizabeth Beale Don Drummond Richard Lipsey Atlantic Provinces Economic Council Queen’s University Simon Fraser University Paul Boothe Stewart Elgie Nancy Olewiler Western University University of Ottawa Simon Fraser University Mel Cappe Glen Hodgson France St-Hilaire University of Toronto Conference Board of Canada Institute for Research on Public Policy This report is a consensus document representing the views -

Environmental Consequences of Road Pricing

Environmental Consequences of Road Pricing A Scoping Paper for The Energy Foundation By Charles Komanoff Komanoff Energy Associates 636 Broadway #602 New York, NY 10012 212-260-5237 [email protected] April 1997 Introduction Road pricing has been called a concept that economists love and everyone else hates – or at least sidesteps. Between those poles stands the transportation reform community, intrigued by pricing’s theoretical potential to reduce highway travel but leery of its impacts on the poor, its kinship to unfettered free-marketeerism and its political unpopularity. Not too long ago, the idea of using road pricing to shape or reduce travel looked a lot like roadkill, as the 1994-95 Republican “revolution” threatened to set back anything smacking of social engineering for at least a generation. Now, however, pricing appears to be climbing off the pavement and onto the policy stage, aided by such factors as state and municipal road-financing deficits; persistent traffic congestion; limited results from non-pricing transportation control measures1,2; and an apparent easing in anti-government sentiment. Equally important, technologies for collecting road tolls efficiently and unobtrusively have gone on line, clearing the way for time-of-day charges and other road-pricing measures.3 If transporta- tion reform advocates have kept their distance from pricing, a growing number now appear willing to give it a closer look. At the same time, however, road-building interests have been advancing their own version of road pricing – new roads or lanes financed by tolls. While these proj- ects do not conform to the environmentalist model of road pricing, which would impose user fees on existing facilities, and at relatively stiff levels to boot, they nonetheless do constitute a form of road pricing.