Philippine Involvement in the Korean War: a Footnote to Rp-Us Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

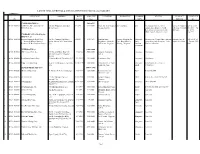

LIST of MPSA APPROVED & APPLICATIONS with STATUS (As of July 2017)

LIST OF MPSA APPROVED & APPLICATIONS WITH STATUS (As of July 2017) "ANNEX C" APPLICANT ADDRESS DATE AREA SIZE LOCATION BARANGAY COMMO- STATUS CONTACT CONTACT ID FILED (Has.) DITY PERSON NO. UNDER PROCESS (1) 5460.8537 1 APSA -000067 XIMICOR, INC. formerly K.C. 105 San Miguel St., San Juan 02/12/96 3619.1000 Diadi, Nueva Vizcaya & San Luis,Balete gold Filed appeal with the Mines Romeo C. Bagarino Fax no. (075) Devt. Phils. Inc. Metro Manila Cordon, Isabela Adjudication Board re: MAB - Director (Country 551-6167 Cp. Decision on adverse claim with Manager) no. 0919- VIMC, issued 2nd-notice dated 6243999 UNDER EVALUATION by the 4/11/16 MGB C.O. (1) 1. APSA -0000122 Kaipara Mining & Devt. Corp. No. 215 Country Club Drive, 10/22/04 1841.7537 Sanchez Mira, Namuac. Bangan, Sta. Magnetite Forwarded to Central Office but was Silvestre Jeric E. (02) 552-2751 ( formerly Mineral Frontier Ayala Alabang Vill. Muntinlupa Pamplona, Abulug & Cruz, Bagu,Masisit, Sand, returned due to deficiencies. Under Lapan - President Fax no. 555- Resources & Development Corp.) City Ballesteros, Cagayan Biduang, Magacan titanium, Final re-evaluation 0863 Vanadium WITHDRAWN (3) 23063.0000 1 APSA -000032 CRP Cement Phil. Inc. 213 Celestial Mary Bldg.950 11/23/94 5000.0000 Antagan, Tumauini, Limestone Withdrawn Arsenio Lacson St. Sampaloc, Isabela Manila 2 APSA -000038 Penablanca Cement Corp. 15 Forest Hills St., New Mla. Q.C. 1/9/1995 9963.0000 Penablanca, Cag. Limestone Withdrawn 3 APSA -000054 Yong Tai Corporation 64-A Scout Delgado St., Quezon 11/24/1995 8100.0000 Cabutunan Pt. & Twin Limestone, Withdrawn per letter dated City Peaks, sta. -

1-Piracy-Tolentino 3-25-2010.Pmd

R. B. TOLENTINO PIRACY REGULATION AND THE FILIPINO’S HISTORICAL RESPONSE TO GLOBALIZATION Rolando B. Tolentino Abstract The essay examines the racial discourse of Moros and Moro-profiling by the state in piracy—sea piracy in olden times and media piracy in contemporary times. Moro piracy becomes a local cosmopolitanism in the Philippines’ attempt to integrate in various eras of global capitalism. From the analysis of media piracy, the Moro “dibidi” (pirated DVD) seller becomes the body that mediates between the Filipinos’ middle-class fantasy of a branded lifestyle and the reality that most Filipinos do not have full access to global consumerism. Using a cultural studies framework, the essay draws a connection between seemingly unlinked events and sources, allowing for a historical and social dialog, past and present, to mix, creating junctures for sites of dialog and critique. Keywords: race formation, Moro, media piracy, conjectural history, middle class Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, piracy includes, among others, “any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any acts of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or properties on board such ship or aircraft; against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State...” (in Eklof 2006, 88). According to the Asia Times Online (Raman 2005) pirate attacks have tripled between 1993 and 2003, with half the incidence happening in Indonesian waters in 2004 (especially in the Strait of Malacca). -

Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1959–1974

Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership: Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1959–1974 By Joseph Paul Scalice A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in South and Southeast Asian Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Associate Professor Jerey Hadler, Chair Professor Peter Zinoman Professor Andrew Barshay Summer 2017 Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership: Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1957-1974 Copyright 2017 by Joseph Paul Scalice 1 Abstract Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership: Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1959–1974 by Joseph Paul Scalice Doctor of Philosophy in South and Southeast Asian Studies University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Jerey Hadler, Chair In 1967 the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (pkp) split in two. Within two years a second party – the Communist Party of the Philippines (cpp) – had been founded. In this work I argue that it was the political program of Stalinism, embodied in both parties through three basic principles – socialism in one country, the two-stage theory of revolution, and the bloc of four classes – that determined the fate of political struggles in the Philippines in the late 1960s and early 1970s and facilitated Marcos’ declaration of Martial Law in September 1972. I argue that the split in the Communist Party of the Philippines was the direct expression of the Sino-Soviet split in global Stalinism. The impact of this geopolitical split arrived late in the Philippines because it was initially refracted through Jakarta. -

Souvenir Program

PAMANTASANG MAHAL Pamantasan, Pamantasang Mahal Nagpupugay kami’t nag-aalay Ng pag-ibig, taos na paggalang Sa patnubay ng aming isipan Karunungang tungo’y kaunlaran Hinuhubog kaming kabataan Maging Pilipinong me’rong dangal Puso’y tigib ng kadakilaan Pamantasang Lungsod ng Maynila Kaming lahat dito’y iyong punla Tutuparin pangarap mo’t nasa Pamantasan kami’y nanunumpa Pamantasan kami’y nanunumpa. Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila Gen. Luna cor. Muralla Sts., Intramuros, Manila 527-90-71 loc. 21 http://www.plm.edu.ph PAMANTASAN NG LUNGSOD NG MAYNILA (University of the City of Manila) taon5 41965 - 2010 Tapat na Pagtalima sa Diwa ng Pamantasang may Malasakit sa Lipunan Hunyo 17-19, 2010 Vision A caring people’s university. Mission Guided by this vision, we commit ourselves to provide quality education to the less privileged but deserving students and develop competent, productive, morally upright professionals, effective transformational leaders and socially responsible citizens. Objectives Anchored upon our vision and mission, we seek to: Equip the stakeholders with the scientific and technological knowledge, skills, attitude, and values for effective and efficient delivery of quality education and services; Conduct relevant and innovative researches for the enrichment of scholarships, advancement of the industry, and development of community both locally and internationally; Promote extension services for community development and establish mutually beneficial linkages with industries and institutions at the local, national, and international levels; Adhere to the values of excellence, integrity, nationalism, social responsibility and trustworthiness; creativity and analytical thinking; and Enhance the goodwill and support of the stakeholders and benefactors for a sustainable caring people’s University towards the transformation of the City of Manila and the nation. -

Old Street Names of Manila Several Streets of Manila Have Been Renamed Through the Years, Sometimes Without Regar

4/30/2016 Angkan ng Leon Mercado at Emiliana Sales Yahoo Groups Old Street Names of Manila Several streets of Manila have been renamed through the years, sometimes without regard to street names as signpost to history. For historian Ambeth Ocampo, old names of the streets of Manila , “in one way reaffirmed and enhanced our culture.” Former names of some streets in Binondo were mentioned by Jose Rizal in his novels. Calle Sacristia (now Ongpin street ) was the street where Rizal’s leading character Crisostomo Ibarra walked the old Tiniente back to his barracks. The house of rich Indio Don Capitan Tiago de los Santos was located in Calle Anloague (now Juan Luna). Only a century ago, the surrounding blocks of Malate and Ermita were traverse only by Calle Real (now M.H. del Pilar Street ) and Calle Nueva (now A Mabini Street ) that followed the curve of the Bay and led to Cavite ’s port. Today’s Roxas Boulevard was underwater then. Along the two main roads were houses and rice fields punctuated by the churches of Malate and Ermita and the military installations like Plaza Militar and Fort San Antonio Abad. After the FilipinoAmerican War, new streets were laid out following the Burnham Plan. In Malate for instance, streets were named after the US states that sent volunteers to crush Aguinaldo’s army. Today, those streets were renamed after Filipinos patriots some became key players in Aguinaldo’s government. It is fascinating to learn that Manila ’s rich heritage is reflected in its streets. Below is a list of current street names and the little history behind it: Andres Soriano Avenue in Intramuros was formerly called theAduana, after the Spanish custom house whose ruins stand on the street. -

The Pentecostal Legacy: a Personal Memoir1

[AJPS 8:2 (2005), pp. 289-310] THE PENTECOSTAL LEGACY: A PERSONAL MEMOIR1 Eli Javier 1. Introduction It has become evident that the task is rather formidable to bring a useful reflection on the history of a Pentecostal body in country in its more than half a century history. At the same time, I feel I have an edge in that the observations were made from the perspective of both an “insider and outsider.” There are personal anecdotes that can be corroborated by those who are still alive. These validate what has been written and experienced by others. Not all correspondence, minutes, and reflections that were published and presented in more formal settings are available to this writer at the moment. This is a handicap of sorts. However, this presentation should not be viewed as the end, but, rather the beginning of our continued pursuit of our “roots”. We owe it to the next generations, should Jesus tarry, to transmit to them our cherished legacy. More materials ought to be written and the “stories” and other oral recitals of how God brought us thus far “through many dangers, toils and snares.” This small contribution of this writer begins with a quick look at personal background to help the audience understand some dynamics of this presentation. 1.1 My Journey of Faith I grew up in a Methodist family and church. My maternal grandparents were among the first converts in our town of Taytay.2 My 1 An earlier version was presented at the Annual Lectureship of the Assemblies of God School of Ministry, Manila, Philippines in September, 2001. -

Piracy and Its Regulation: the Filipino's Historical Response to Globalization by Rolando B. Tolentino, University of the Phil

Piracy and Its Regulation: The Filipino’s Historical Response to Globalization by Rolando B. Tolentino, University of the Philippines Film Institute (Paper presented at the workshop on media piracy and intellectual property in Southeast Asia, UP CMC Auditorium, 24 November 2006. Draft, not for citation. For comments, email [email protected] .) Piracy is popularly defined as a “robbery committed at sea, or sometimes on the shore, by an agent without a commission from a sovereign nation.” 1 Pirate attacks have tripled between 1993 and 2003, with half the incidence happening in Indonesian waters in 2004, and of which, the majority occurred in the Strait of Malacca. 2 There is much to be feared in sea piracy as some 50,000 commercial ships ply the water routes between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, off the Somali coast, and in the Strait of Malacca and Singapore. 3 These cargo ships holding tons of steel containers, after all, are the backbone of capitalist trade, allowing the transfer of bulk materials, produce, and waste. Media piracy, therefore, would fall into a related definition because it is an act of omission committed against a sovereign body, usually a business corporation holding the intellectual property right to the contested object, and thus protected by the corporation’s nation-state. However, media piracy does not only happen through sea lines (but in the Philippine case, it does 4), it also gets literally and figuratively reproduced technologically. A duplicating machine can reproduce 20,000 copies of music, film, games, and software per day. So invested are business corporations and their nation- states that there is almost a paranoia in protecting their objects of profit from any further loss—in seaborne piracy, estimated losses are US$13-16 billion per year 5; in media piracy, US companies lose supposedly as much as $250 billion per year, although another estimate places it at $60 billion. -

“Total Community Response”: Performing the Avant-Garde As a Democratic Gesture in Manila

“Total Community Response”: Performing the Avant-garde as a Democratic Gesture in Manila Patrick D. Flores Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, Volume 1, Number 1, March 2017, pp. 13-38 (Article) Published by NUS Press Pte Ltd DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/sen.2017.0001 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/646476 [ Access provided at 3 Oct 2021 20:14 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] “Total Community Response”: Performing the Avant-garde as a Democratic Gesture in Manila PATRICK D. FLORES “This nation can be great again.” This was how Ferdinand Marcos enchanted the electorate in 1965 when he won his first presidential election at a time when the Philippines “prided itself on being the most ‘advanced’ in the region”.1 In his inaugural speech titled “Mandate to Greatness”, he spoke of a “national greatness” founded on the patriotism of forebears who had built the edifice of the “first modern republic in Asia and Africa”.2 Marcos conjured prospects of encompassing change: “This vision rejects and discards the inertia of centuries. It is a vision of the jungles opening up to the farmers’ tractor and plow, and the wilderness claimed for agriculture and the support of human life; the mountains yielding their boundless treasure, rows of factories turning the harvests of our fields into a thousand products.” 3 This line on greatness may prove salient in the discussion of the avant- garde in Philippine culture in the way it references “greatness” as a marker of the “progressive” as well as of the “massive”. -

THE XIAO TIME PHILIPPINE HISTORY INDEX Dahil Sa Pangangailangan Ng Maraming Guro Na Magkaroon Ng Mga Materyal Para Sa Kanilang O

THE XIAO TIME PHILIPPINE HISTORY INDEX Dahil sa pangangailangan ng maraming guro na magkaroon ng mga materyal para sa kanilang online classes sa panahon ng Corona Virus, aking sinimulan ngayong umaga ang paglikha ng index ng mga Xiao Time videos na magkakasunod-sunod ayon sa pinag-aaralan sa kasaysayan ng Pilipinas o sa Rizal. Karamihan ng lahat ng 643 episodes na ginawa sa loob ng limang taon (2012-2017) ay narito, kabilang na ang Project Vinta at Project Saysay series na tumuloy hanggang 2018. Sa panonood nito, magkakaroon ka na ng gagap ng pagkakasunod-sunod ng kasaysayan ng Pilipinas. Mas madali na din lamang mahahanap ang mga paksa dahil nakaayos na ito sa bawat tema o maaaring i-search sa isang listahan na ito. Antagal ko nang pangarap na magawa ito, sa wakas nasimulan ko rin. Sa paggunita ngayon ng mahalagang ika-499 guning taong pagdating ni Magellan sa Pilipinas, 16 Marso 2020, aking inilalabas ang pinakaunang index ng Xiao Time videos ukol sa Kasaysayang ng Pilipinas. Nirebisa 29 Marso 2020, 14 Abril 2020. Ano ang Xiao Time: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=3skRebu_rBI Pagpupugay sa Xiao Time ni John Ray Ramos ng Proyekto: https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=2070557653171157&substory_index=0&id=1550940948 466166 XIAO TIME: AKO AY PILIPINO episode index Mga Nilalaman: Ano ang Kasaysayan Historiograpiya Pagkakakilanlang Pilipino PAMAYANAN Sinaunang Bayan (pre-1565) Islam sa Pilipinas (Ibang Paksa Ukol sa Islam nasa XXV) BAYAN Conquista (1865-1898) Katolisismo sa Pilipinas (1821-1898) Ika-19 na Siglo (1807-1872) Propagandismo -

Monsoon Marketplace: Inscriptions and Trajectories of Consumer Capitalism and Urban Modernity in Singapore and Manila

Monsoon Marketplace: Inscriptions and Trajectories of Consumer Capitalism and Urban Modernity in Singapore and Manila By Fernando Piccio Gonzaga IV A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Trinh T. Minh-ha, Chair Professor Samera Esmeir Professor Jeffrey Hadler Spring 2014 ©2014 Fernando Piccio Gonzaga IV All Rights Reserved Abstract Monsoon Marketplace: Inscriptions and Trajectories of Consumer Capitalism and Urban Modernity in Singapore and Manila by Fernando Piccio Gonzaga IV Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric University of California, Berkeley Professor Trinh T. Minh-ha, Chair This study aims to trace the genealogy of consumer capitalism, public life, and urban modernity in Singapore and Manila. It examines their convergence in public spaces of commerce and leisure, such as commercial streets, department stores, amusement parks, coffee shops, night markets, movie theaters, supermarkets, and shopping malls, which have captivated the residents of these cities at important historical moments during the 1930s, 1960s, and 2000s. Instead of treating capitalism and modernity as overarching and immutable, I inquire into how their configuration and experience are contingent on the historical period and geographical location. My starting point is the shopping mall, which, differing from its suburban isolation in North America and Western Europe, dominates the burgeoning urban centers of Southeast Asia. Contrary to critical and cultural theories of commerce and consumption, consumer spaces like the mall have served as bustling hubs of everyday life in the city, shaping the parameters and possibilities of identity, collectivity, and agency without inducing reverie or docility. -

Download This PDF File

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines Dramatics at the Ateneo de Manila: A History of Three Decades, 1921-1952 Review Author: Doreen G. Fernandez Philippine Studies vol. 25, no. 4 (1977) 492–496 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Fri June 27 13:30:20 2008 492 PHILIPPINE STUDIES in other areas of dissent down through the centuries, it might be revised. Wken many theologians disagree with official non-infallible Church teaching, we should reflect on the words of Yves Congar, 09.(Theology Digest 25 [Spring 19771: 15-20) writing on "The Magisterium and Theologians - A Short History." He concludes an authoritative and thought-provoking article by asking for a rethinking of the relationship between theologians and the magisterium to prevent the magisterium from being isolated from the living reality of the Church. The theologians have their own original charism and service to the Church that must be recognized. "Theologians should not be regarded only from the point of view of their dependence on the magiste- rium" (p.