The Pentecostal Legacy: a Personal Memoir1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6. Birth, Rapid Growth, Stabilization and Integration of Sunbogeum Pentecostalism (1953-1972)

6. Birth, rapid growth, stabilization and integration of Sunbogeum pentecostalism (1953-1972) 6.1. INTRODUCTION In this chapter we describe the birth, growth and indigenization of Korean pente- costalism in Korea (Sunbogeum pentecostalism) in two decades (1953-1972). The three most important factors that formed Sunbogeumism in this period were the support of the American Assemblies of God (missions and theological aspect), the activity of Yonggi Cho (leadership aspect), and the receptivity of Korean religiosity (socio-cultural aspect). From the time that the armistice between the United Nations and North Korea was signed in July 1953, the South Koreans began to enjoy freedom for the first time in many decades since the Japanese interference (1876). The modernization of Korea began to be realized in the true sense of the word by Koreans themselves. Christianity also began to be fully active for the first time in two centuries since its introduction. Classical pentecostalism in Korea also began to flower at this time, finding the right supporter, the right personality, and the right soil. Since 1961, through military revolution and regime, Korean society has experienced a wide spectrum of changes resulting from rapid industralization and economic revolution. Such a situation provided Korean pentecostalism with an opportunity to flourish in it.1 Even though pentecostal theology was introduced through missionaries, it was fully developed by Korean pentecostals in Korean soil. We call this Sunbogeum pentecostalism. While American pentecostals planted pentecostalism in Korea through theology, organization, and finances, the Koreans received them and tried to re-produce an ‘original pentecostalism’ according to Biblical principles. -

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

ELEAZAR S. FERNANDEZ Professor Of

_______________________________________________________________________________ ELEAZAR S. FERNANDEZ Professor of Constructive Theology United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities 3000 Fifth Street Northwest New Brighton, Minnesota 55112, U.S.A. Tel. (651) 255-6131 Fax. (651) 633-4315 E-Mail [email protected] President, Union Theological Seminary, Philippines Sampaloc 1, Dasmarinas City, Cavite, Philippines E-Mail: [email protected] Mobile phone: 63-917-758-7715 _______________________________________________________________________________ PROFESSIONAL PREPARATION VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY, Nashville, Tennessee, U.S.A. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD.) Major: Philosophical and Systematic Theology Minor: New Testament Date : Spring 1993 PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.A. Master of Theology in Social Ethics (ThM), June 1985 UNION THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, Cavite, Philippines Master of Divinity (MDiv), March 1981 Master's Thesis: Toward a Theology of Development Honors: Cum Laude PHILIPPINE CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY, Cavite, Philippines Bachelor of Arts in Psychology (BA), 1980 College Honor/University Presidential Scholarship THE COLLEGE OF MAASIN, Maasin, Southern Leyte, Philippines Associate in Arts, 1975 Scholar, Congressman Nicanor Yñiguez Scholarship PROFESSIONAL WORK EXPERIENCE President and Academic Dean, Union Theological Seminary, Philippines, June 1, 2013 – Present. Professor of Constructive Theology, United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities, New Brighton, Minnesota, July 1993-Present. Guest/Mentor -

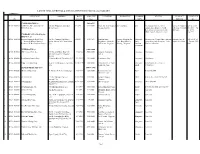

NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Child & Youth Welfare (Residential) ACCREDITED a HOME for the ANGELS CHILD Mrs

Directory of Social Welfare and Development Agencies (SWDAs) with VALID REGISTRATION, LICENSED TO OPERATE AND ACCREDITATION per AO 16 s. 2012 as of March, 2015 Name of Agency/ Contact Registration # License # Accred. # Programs and Services Service Clientele Area(s) of Address /Tel-Fax Nos. Person Delivery Operation Mode NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Child & Youth Welfare (Residential) ACCREDITED A HOME FOR THE ANGELS CHILD Mrs. Ma. DSWD-NCR-RL-000086- DSWD-SB-A- adoption and foster care, homelife, Residentia 0-6 months old NCR CARING FOUNDATION, INC. Evelina I. 2011 000784-2012 social and health services l Care surrendered, 2306 Coral cor. Augusto Francisco Sts., Atienza November 21, 2011 to October 3, 2012 abandoned and San Andres Bukid, Manila Executive November 20, 2014 to October 2, foundling children Tel. #: 562-8085 Director 2015 Fax#: 562-8089 e-mail add:[email protected] ASILO DE SAN VICENTE DE PAUL Sr. Enriqueta DSWD-NCR RL-000032- DSWD-SB-A- temporary shelter, homelife Residentia residential care -5- NCR No. 1148 UN Avenue, Manila L. Legaste, 2010 0001035-2014 services, social services, l care and 10 years old (upon Tel. #: 523-3829/523-5264/522- DC December 25, 2013 to June 30, 2014 to psychological services, primary community-admission) 6898/522-1643 Administrator December 24, 2016 June 29, 2018 health care services, educational based neglected, Fax # 522-8696 (Residential services, supplemental feeding, surrendered, e-mail add: [email protected] Care) vocational technology program abandoned, (Level 2) (commercial cooking, food and physically abused, beverage, transient home) streetchildren DSWD-SB-A- emergency relief - vocational 000410-2010 technology progrm September 20, - youth 18 years 2010 to old above September 19, - transient home- 2013 financially hard up, (Community no relative in based) Manila BAHAY TULUYAN, INC. -

LIST of MPSA APPROVED & APPLICATIONS with STATUS (As of July 2017)

LIST OF MPSA APPROVED & APPLICATIONS WITH STATUS (As of July 2017) "ANNEX C" APPLICANT ADDRESS DATE AREA SIZE LOCATION BARANGAY COMMO- STATUS CONTACT CONTACT ID FILED (Has.) DITY PERSON NO. UNDER PROCESS (1) 5460.8537 1 APSA -000067 XIMICOR, INC. formerly K.C. 105 San Miguel St., San Juan 02/12/96 3619.1000 Diadi, Nueva Vizcaya & San Luis,Balete gold Filed appeal with the Mines Romeo C. Bagarino Fax no. (075) Devt. Phils. Inc. Metro Manila Cordon, Isabela Adjudication Board re: MAB - Director (Country 551-6167 Cp. Decision on adverse claim with Manager) no. 0919- VIMC, issued 2nd-notice dated 6243999 UNDER EVALUATION by the 4/11/16 MGB C.O. (1) 1. APSA -0000122 Kaipara Mining & Devt. Corp. No. 215 Country Club Drive, 10/22/04 1841.7537 Sanchez Mira, Namuac. Bangan, Sta. Magnetite Forwarded to Central Office but was Silvestre Jeric E. (02) 552-2751 ( formerly Mineral Frontier Ayala Alabang Vill. Muntinlupa Pamplona, Abulug & Cruz, Bagu,Masisit, Sand, returned due to deficiencies. Under Lapan - President Fax no. 555- Resources & Development Corp.) City Ballesteros, Cagayan Biduang, Magacan titanium, Final re-evaluation 0863 Vanadium WITHDRAWN (3) 23063.0000 1 APSA -000032 CRP Cement Phil. Inc. 213 Celestial Mary Bldg.950 11/23/94 5000.0000 Antagan, Tumauini, Limestone Withdrawn Arsenio Lacson St. Sampaloc, Isabela Manila 2 APSA -000038 Penablanca Cement Corp. 15 Forest Hills St., New Mla. Q.C. 1/9/1995 9963.0000 Penablanca, Cag. Limestone Withdrawn 3 APSA -000054 Yong Tai Corporation 64-A Scout Delgado St., Quezon 11/24/1995 8100.0000 Cabutunan Pt. & Twin Limestone, Withdrawn per letter dated City Peaks, sta. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Pentecostal Movement.Qxd

The Pentecostal Movement © 2010 Rodney Shaw Charles Parham, Topeka, Kansas, 1901 1. Holiness preacher • Holiness preachers equated "baptism in the Spirit" in Acts with their doc- trine of sanctification. • “Pentecostal" began to be used a lot. “Back to Pentecost" became a rally- ing cry. • Some (a minority) began to seek a third experience of the baptism of the Holy Ghost (and fire), though they did not expect tongues. 2. Bethel Bible College, Topeka, Kansas 3. Revivals in the Midwest, Houston, etc. 4. A third work of grace: saved, sanctified, filled with the Holy Ghost. Williams Seymour and Azusa, Los Angeles, California, 1906 1. Holiness minister from Louisiana 2. Student of Parham in Houston 3. Invited to preach in Los Angeles 4. Locked out of church, Lee Home, Asberry Home on Bonnie Brae Street, Azusa Street Mission 5. Three-year revival 6. Spread around the world 7. Spirit baptism was normalized Finished work, William Durham, 1911 1. Baptist minister who had an experience he understood to be sanctification. 2. Received the baptism of the Spirit at Azusa Street in 1907. 3. Durham's conclusions (See David K. Bernard, History of Christian Doctrine, Vol. III): • The baptism of the Spirit was a different kind of experience. Notes "I saw clearly, for the first time, the difference between having the influ- ence and presence of the Spirit with us, and having Him dwell within us in person." • He could not simply "claim" the baptism of the Spirit. "I could not kneel at the altar, and claim the Holy Ghost and go away. This was a real experience. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 467 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. their advice and thoughts; Andy Pownall; Gerry OUR READERS Deegan; all you sea urchins – you know who Many thanks to the travellers who used you are, and Jim Boy, Zaza and Eddie; Alexan- the last edition and wrote to us with der Lumang and Ronald Blantucas for the lift helpful hints, useful advice and interesting with accompanying sports talk; Maurice Noel anecdotes: ‘Wing’ Bollozos for his insight on Camiguin; Alan Bowers, Angela Chin, Anton Rijsdijk, Romy Besa for food talk; Mark Katz for health Barry Thompson, Bert Theunissen, Brian advice; and Carly Neidorf and Booners for their Bate, Bruno Michelini, Chris Urbanski, love and support. -

Metro Manila

Alcoholics Anonymous Philippines Meeting Schedule 2017 Metro Manila TIME/DAY 12:30PM 6:30PM 7:00PM 7:30PM 164 Group (English/Tagalog) Holy Trinity Church (across San Antonio Plaza) Monday 48-A McKinley Rd. Forbes Park, Makati Monet – +63 917 5384040 Fort Serenity Group – Came To Believe Tuesday UCC Cafe Terrace, 26th Street, Forbes Wood Town Center Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City Contact Phil +63 939 421 3829 Primary Purpose Group (English/Tagalog - Open) Makati Medical Center 3rd F Neuro-Science Center Conference Rm. (across Pancake House) No. 2 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City Fort Serenity Group – Daily Refelections New Manila Group ************************************************ ********* Wednesday 55-A 11th Street, New Manila, Quezon City UCC Cafe Terrace, 26th Street, Forbes Wood Town Center Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City Call Fernan – +63 915 765 4789 Purple Tree Group Contact Phil +63 939 421 3829 The Purple Tree Bed and Breakfast, President’s Avenue, Parañaque, Metro Manila Call Jovi – +63 917 819 4697 Call JJ – +63 917 521 6621 Thursday Alcoholics Anonymous Philippines Meeting Schedule 2017 Metro Manila TIME/DAY 12:30PM 6:30PM 7:00PM 7:30PM Primary Purpose Group (English/Tagalog - Open) Makati Medical Center 3rd F Neuro-Science Center Conference Rm. (across Pancake House) No. 2 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City ************************************************ Friday ********* Fort Serenity Group – Daily Refelections UCC Cafe Terrace, 26th Street, Forbes Wood Town Center Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City Contact Phil +63 939 421 3829 Manila Bay Group Primary Purpose Group (English/Tagalog - Open) UCC Cafe Terrace, 26th Street, Forbes Wood Town Amici Restaurant (Don Bosco School) Saturday Center Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City A. -

1-Piracy-Tolentino 3-25-2010.Pmd

R. B. TOLENTINO PIRACY REGULATION AND THE FILIPINO’S HISTORICAL RESPONSE TO GLOBALIZATION Rolando B. Tolentino Abstract The essay examines the racial discourse of Moros and Moro-profiling by the state in piracy—sea piracy in olden times and media piracy in contemporary times. Moro piracy becomes a local cosmopolitanism in the Philippines’ attempt to integrate in various eras of global capitalism. From the analysis of media piracy, the Moro “dibidi” (pirated DVD) seller becomes the body that mediates between the Filipinos’ middle-class fantasy of a branded lifestyle and the reality that most Filipinos do not have full access to global consumerism. Using a cultural studies framework, the essay draws a connection between seemingly unlinked events and sources, allowing for a historical and social dialog, past and present, to mix, creating junctures for sites of dialog and critique. Keywords: race formation, Moro, media piracy, conjectural history, middle class Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, piracy includes, among others, “any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any acts of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or properties on board such ship or aircraft; against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State...” (in Eklof 2006, 88). According to the Asia Times Online (Raman 2005) pirate attacks have tripled between 1993 and 2003, with half the incidence happening in Indonesian waters in 2004 (especially in the Strait of Malacca). -

Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1959–1974

Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership: Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1959–1974 By Joseph Paul Scalice A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in South and Southeast Asian Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Associate Professor Jerey Hadler, Chair Professor Peter Zinoman Professor Andrew Barshay Summer 2017 Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership: Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1957-1974 Copyright 2017 by Joseph Paul Scalice 1 Abstract Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership: Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1959–1974 by Joseph Paul Scalice Doctor of Philosophy in South and Southeast Asian Studies University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Jerey Hadler, Chair In 1967 the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (pkp) split in two. Within two years a second party – the Communist Party of the Philippines (cpp) – had been founded. In this work I argue that it was the political program of Stalinism, embodied in both parties through three basic principles – socialism in one country, the two-stage theory of revolution, and the bloc of four classes – that determined the fate of political struggles in the Philippines in the late 1960s and early 1970s and facilitated Marcos’ declaration of Martial Law in September 1972. I argue that the split in the Communist Party of the Philippines was the direct expression of the Sino-Soviet split in global Stalinism. The impact of this geopolitical split arrived late in the Philippines because it was initially refracted through Jakarta. -

Global University Catálogo De La Facultad De Estudios De Pregrado De Biblia Y Teología

2017 GLOBAL UNIVERSITY CATÁLOGO DE LA FACULTAD DE ESTUDIOS DE PREGRADO DE BIBLIA Y TEOLOGÍA 1211 South Glenstone Avenue • Springfield, Missouri 65804-0315 USA Teléfono: 800.443.1083 • 417.862.9533 • Fax 417.862.0863 Correo electrónico: [email protected] • Sitio Web: www.globaluniversity.edu ©2017 Global University Todos los derechos reservados ÍNDICE De parte del Presidente ..............................................4 Crédito por aprendizaje basado en la experiencia .........23 De parte del Preboste .................................................5 Admisión en un programa de estudio para un segundo título de pregrado .................24 Información general .................................................. 6 Prólogo ........................................................................ 6 La orientación estudiantil ............................................24 Historia ........................................................................ 6 El número de alumno y el carné ....................................24 Misión de Global University........................................... 6 Rendimiento académico aceptable ..............................24 Declaración Doctrinal.....................................................7 La transferencia de crédito de Global University ...........25 Declaración de política de no discriminacion ..................7 Los expedientes académicos de los Oficina Internacional de Global University ......................7 créditos de Global University ......................................