Thinking Outside the Box: Intersectionality As a Hate Crime Research Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definitions of Oppression, Dehumanization and Exploitation

Definitions of Oppression, Dehumanization and Exploitation Oppression The dictionary definition ((Webster's Third International Dictionary): "Unjust or cruel exercise of authority or power especially by the imposition of burdens; the condition of being weighed down; an act of pressing down; a sense of heaviness or obstruction in the body or mind." The Latin origin has oppressus as the past participle of opprimere, or to press down. Amongst the synonyms: the word subjugation. The Social Work Dictionary, ed. Robert L. Barker defines oppression as: "The social act of placing severe restrictions on an individual, group or institution. Typically, a government or political organization that is in power places these restrictions formally or covertly on oppressed groups so that they may be exploited and less able to compete with other social groups. The oppressed individual or group is devalued, exploited and deprived of privileges by the individual or group which has more power." (Barker, 2003) The Blackwell Dictionary of Sociology has an excellent definition of social oppression: "Social oppression is a concept that describes a relationship between groups or categories of between groups or categories of people in which a dominant group benefits from the systematic abuse, exploitation, and injustice directed toward a subordinate group. The relationship between whites and blacks in the United States and South Africa, between social classes in many industrial societies, between men and women in most societies, between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland - all have elements of social oppression in that the organization of social life enables those who dominate to oppress others. Relationships between groups and relationships between groups and social categories, it should not be confused with the oppressive behavior of individuals. -

A Comparative Analysis of Hate Crime Legislation

A Comparative Analysis of Hate Crime Legislation A Report to the Hate Crime Legislation Review James Chalmers and Fiona Leverick University of Glasgow, July 2017 i A Comparative Analysis of Hate Crime Legislation: A Report to the Hate Crime Legislation Review July 2017 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ________________________________________________ 1 1. WHAT IS HATE CRIME? ________________________________________ 4 2. HATE CRIME LEGISLATION IN SCOTLAND __________________________ 7 3. JUSTIFICATIONS FOR PUNISHING HATE CRIME MORE SEVERELY ______ 23 4. MODELS OF HATE CRIME LEGISLATION __________________________ 40 5. CHOICE OF PROTECTED CHARACTERISTICS _______________________ 52 6. HATE SPEECH AND STIRRING UP OFFENCES _______________________ 68 7. HATE CRIME LEGISLATION IN SELECTED JURISDICTIONS _____________ 89 8. APPROACHES TAKEN IN OTHER JURISDICTIONS RELEVANT TO THE OFFENSIVE BEHAVIOUR AT FOOTBALL AND THREATENING COMMUNICATIONS (SCOTLAND) ACT 2012 ____________________________________________________ 134 ii INTRODUCTION In January 2017, the Scottish Government announced a review of hate crime legislation, chaired by Lord Bracadale.1 Lord Bracadale requested that, to assist the Review it its task, we produce a comparative report detailing principles underpinning hate crime legislation and approaches taken to hate crime in a range of jurisdictions. Work on this report commenced in late March 2017 and the final report was submitted to the Review in July 2017. Chapter 1 (What is Hate Crime?) explores what is meant by the term “hate crime”, noting that different definitions may properly be used for different purposes. It notes that the legislative response to hate crime can be characterised by the definition offered by Chakraborti and Garland: the creation of offences, or sentencing provisions, “which adhere to the principle that crimes motivated by hatred or prejudice towards particular features of the victim’s identity should be treated differently from ‘ordinary’ crimes”. -

Disability Studies 1

Disability Studies 1 DST:1101 Introduction to Disability Studies 3 s.h. Introduction and overview of important topics and discussions Disability Studies that pertain to the experience of being disabled; contrast between medical and social models of disability; focus on Chair, Department of Health and Human how disability has been constructed historically, socially, and Physiology politically in an effort to distinguish myth and stigma from • Warren G. Darling reality; perspective that disability is part of human experience and touches everyone; interdisciplinary with many academic Coordinator, Disability Studies areas that offer narratives about experience of disability. GE: • Kristina M. Gordon (Health and Human Physiology) Diversity and Inclusion. DST:1200 Disabilities and Inclusion in Writing and Film Undergraduate certificate: disability studies Around the World 3 s.h. Website: https://clas.uiowa.edu/hhp/undergraduate/ Exploration of human experiences of dis/ability and exclusion/ disability-studies-certificate inclusion. Taught in English. GE: Diversity and Inclusion. Same Disability studies examines disability as a social, cultural, as GHS:1200, GRMN:1200, WLLC:1200. historical, and political phenomenon rather than focusing DST:3102 Culture and Community in Human on its clinical, medical, or therapeutic aspects. It is an Services 2-3 s.h. interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary field that draws on Influence of social issues (e.g., diversity, equity) on human scholarship from diverse disciplines, including anthropology, services; -

The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted Finding New Support for Embodied and Imagined Differences in Contemporary Art

The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted Finding New Support for Embodied and Imagined Differences in Contemporary Art Amanda Cachia Independent scholar and PhD candidate The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted This article undertakes analyses of the contemporary American artists Robert Gober and Cindy Sherman to argue that they use the tropes of the obscene, abject, and traumatic—as discussed by Hal Foster—to make literal and metaphorical reference to David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder’s narrative prosthesis and its “truth,” while simultaneously leaving out the lived experience of disability. Consideration is given to the works of artists Carmen Papalia and Mike Parr, who use complex embodiment as a new methodology to signify empowerment and agency over what we might previously have considered the obscene, abject, or traumatic. They transform traditional understandings of the “prosthetic” within the specific rhetoric of disability. Introduction Why is it so de rigueur for contemporary artists to use disabled embodiment as a means to convey troubled emotional states, as a narrative and literal prosthesis? Narrative prosthesis is a term originally developed by David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, where the disabled body is often inserted into literary, or in this case, visual narratives as a metaphorical opportunity. The disabled body or character is used as a type of crutch or supporting device that allows the narrative to take a turn or a new direction, but often the relationship between the story itself and the disabled body is one based on exploi- tation. “Through the corporeal metaphor,” Mitchell and Snyder articulate, “the disabled or otherwise different body may easily become a stand-in for more abstract notions of the human condition, as universal or nationally specific; thus the textual (disembodied) project depends upon—and takes advantage of—the materiality of the body” (50). -

Still Getting Away with Murder: Disability Hate Crime in England

Still Getting Away with Murder A report about Disability Hate Crime in England Disability hate crime: this means when somebody commits a crime against a Disabled person because of their impairment. Impairment: in the document, this is used to talk about a Disabled person’s medical condition, diagnosis or difference. This could be physical or mental. Not all Disabled people are comfortable with the word ‘impairment’. However, we are not using this word to talk about who the person is. That is a personal choice. Part A – A Summary of the report One out of five Disabled people say that they have faced unkind or threatening behaviour or even been attacked (Inclusion London, 2020). Disabled people: in this document, this means people with impairments who choose to be part of the Disabled people's movement in the UK. These people stand up for rights for Disabled people across the country. This document looks at the fight against disability hate crime in England over the last 10 years. In 2008, we wrote a report called Getting Away With Murder . Getting Away with Murder Report: this was a report that was written in 2008 by Katharine Quarmby, together with Disability Now, the UK Disabled People’s Council and Scope. It looked at Disabled people’s experiences of hate crime in 2008. Since then, there have been lots of changes in the ways that disability hate crime is dealt with. This document looks at how things have changed since the last report was written. It is hard to say how much change there has been over the last 12 years. -

Harassment and Victimisation Introduction

Harassment and victimisation Introduction Stockholm University is to be characterised by its excellent environment for work and study. All employees and students shall be treated equally and with respect. At Stockholm University we shall jointly safeguard our work and study environment. A good environment enables creative development and excellent outcomes for work and study. At Stockholm University, victimisation, harassment associated with discrimination on any grounds and sexual harassment are unacceptable and must not take place. Victimisation, harassment and sexual harassment all jeopardise the affected person's job satisfaction and chances of success in work or study. As soon as the university becomes aware that someone has been affected, action will be taken immediately. In this brochure, Stockholm University explains • the forms that victimisation, harassment and sexual harassment may take, • what you can do if you or someone else becomes subjected to such behaviour, • the university's responsibilities, • the sanctions faced by those subjecting a person to victimisation, harassment or sexual harassment. Astrid Söderbergh Widding Vice-Chancellor Production: Human Resources Office, Student Services, Council for Equal Opportunities and Equality, and Matador kommunikation. Illustrations: Jan Ed. Printing: Ark-Tryckaren, 2015. 3 What is victimisation? All organisations experience occasional differences of opinion, conflicts and difficulties in working together. However, these occasional conflicts are not considered victimisation or bullying. Victimisation is defined as recurrent reprehensible or negative actions directed against individuals and that may lead to the person experiencing it being marginalised. Examples include deliberate insults, demeaning treatment, ostracism, withholding of information, persecution or threats. Victimisation brings with it the risk that individuals as well as entire groups will be adversely affected, in both the short and long terms. -

Fostering Employment for People with Intellectual Disability: the Evidence to Date

Fostering employment for people with intellectual disability: the evidence to date Erin Wilson and Robert Campain August 2020 This document has been prepared by the Centre for Social Impact Swinburne for Inclusion Australia as part of the ‘Employment First’ project, funded by the National Disability Insurance Agency. ‘ About this report This report presents a set of ‘evidence pieces’ commissioned by Inclusion Australia to inform the creation of a website developed by Inclusion Australia as part of the ‘Employment First’ (E1) project. Suggested citation Wilson, E. & Campain, R. (2020). Fostering employment for people with intellectual disability: the evidence to date, Hawthorn, Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology. Research team The research project was undertaken by the Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology, under the leadership of Professor Erin Wilson together with Dr Robert Campain. The research team would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ms Jenny Crosbie, Dr Joanne Qian, Ms Aurora Elmes, Dr Andrew Joyce and Mr James Kelly (of the Centre for Social Impact) and Dr Kevin Murfitt (Deakin University) who have collaborated in the sharing of information and analysis regarding a range of research related to the employment of people with a disability. Page 2 ‘ Contents Background 5 About the research design 6 Structure of this report 7 Synthesis: How can employment of people with intellectual disability be fostered? 8 Evidence piece 1: Factors positively influencing the employment of people -

ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION and SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE in COLLEGE WOMEN Marina Leigh Costanzo

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 2018 ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE IN COLLEGE WOMEN Marina Leigh Costanzo Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Recommended Citation Costanzo, Marina Leigh, "ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE IN COLLEGE WOMEN" (2018). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11264. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11264 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE IN COLLEGE WOMEN By MARINA LEIGH COSTANZO B.A., University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2010 M.A., University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, CO, 2013 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Clinical Psychology The University of Montana Missoula, MT August 2018 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Christine Fiore, Chair Psychology Laura Kirsch Psychology Jennifer Robohm Psychology Gyda Swaney Psychology Sara Hayden Communication Studies INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE ii Costanzo, Marina, PhD, Summer 2018 Clinical Psychology Abstract Chairperson: Christine Fiore Sexualized violence on college campuses has recently entered the media spotlight. One in five women are sexually assaulted during college and over 90% of these women know their attackers (Black et al., 2011; Cleere & Lynn, 2013). -

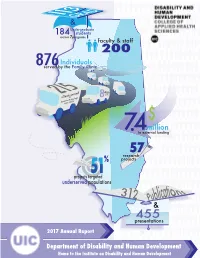

Annual-Report-2017-Web.Pdf

GRAD & Undergraduate 184 students across 7programs faculty & staff 200 Individuals 876served by the Family Clinic Clientsby served Assistive Technology Units (ATUs) $ million 7.4In external funding research57 % projects projects targeted51 underserved populations 2 E.Kief 2017 & 455 presentations 2017 Annual Report Department of Disability and Human Development Home to the Institute on Disability and Human Development Table of Contents 3 - Post-Doctoral Program Trains Tomorrow’s Leaders 4 - PhD Students Expand their Horizons Internationally 5 - First Undergraduate Student Graduates from DHD’s Major 6 - IL LEND Trainees Learn by Doing 7 - DHD Promotes Systems Change Through Training and Advocacy 8 - DHD Awards Three Trainees Diversity Fellows 9 - DHD Alumni as Leaders in Policy and Practice 10 - Assistive Technology Unit Promotes Independence for People with Disabilities 11 - Family Clinic Provides Community Based Programs 12 - Faculty Committed to Scholarship and Activism 13 - RRTCDD Promotes the Health of People with IDD 14 - Continuing the Legacy of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by Bridging Research, Training, and Education 15 - Students Recognized for their Achievements Welcome Statement We are pleased to present the 2016-2017 Annual Report for the Department of Disability and Human Development (DHD) and its Institute on Disability and Human Development (IDHD). It has been an exciting year for DHD as we now offer a full range of academic programs, from an undergraduate minor and major to a PhD program in Disability Studies and graduate certificates in Assistive Technology or Disability Ethics. We are attracting over 600 students to our courses each semester. Additionally, we are now able to offer teaching assistantships to our doctoral students. -

Research Into Cyberbullying and Cyber Victimisation

Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2007, 23(4), 435-454 Bullying in the new playground: Research into cyberbullying and cyber victimisation Qing Li University of Calgary This study examines the nature and extent of adolescents’ cyberbullying experiences, and explores the extent to which various factors, including bullying, culture, and gender, contribute to cyberbullying and cyber victimisation in junior high schools. In this study, one in three adolescents was a cyber victim, one in five was a cyberbully, and over half of the students had either experienced or heard about cyberbullying incidents. Close to half of the cyber victims had no idea who the predators were. Culture and engagement in traditional bullying were strong predictors not only for cyberbullying, but also for cyber victimisation. Gender also played a significant role, as males, compared to their female counterparts, were more likely to be cyberbullies. Cyberbullying and cyber victimisation School bullying has been widely recognised as a serious problem and it is particularly persistent and acute during junior high and middle school periods (National Center for Educational-Statistics, 1995). In the USA, “up to 15% of students … are frequently or severely harassed by their peers. … Only a slim majority of 4th through 12th graders … (55.2%) reported neither having been picked on nor picking on others” (Hoover & Olsen, 2001). Universally, bullying is reported as a significant problem in many countries of the world including European countries, North America, and Japan (Smith et al., 1999), suggesting that bullying may play a important role in adolescents’ life in many societies. More importantly, it is reported that in many cases of school shootings, the bully played a major role (Dedman, 2001; Markward, Cline & Markward, 2002). -

Victimisation from Physical Punishment and Intimate Partner Aggression in South Africa: the Role of Revictimisation

Victimisation from Physical Punishment and Intimate Partner Aggression in South Africa: The Role of Revictimisation Master’s Thesis in Peace, Mediation and Conflict Research Developmental Psychology Magret Tsoahae, 1901696 Supervisor: Karin Österman Faculty of Education and Welfare Studies Åbo Akademi University, Finland Spring 2021 Magret Tsoahae Abstract Aim: The aim of the study was to investigate victimisation from physical punishment during childhood, victimisation from an intimate partner as an adult, and psychological concomitants. Method: A questionnaire was completed by 190 females, 32 males, and three who did not state their sex. The respondents where from South Africa. The mean age was 40.0 years (SD 12.2) for females, and 29.7 years (SD 9.9) for males. Results: For females, victimisation from physical punishment correlated significantly with victimisation from intimate partner controlling behaviours. For females, but not for males, victimisation from physical punishment during childhood correlated positively with depression and anxiety later in life. For both females and males, a high significant correlation was found between victimisation from intimate partner physical aggression and controlling behaviours, intimate partner physical aggression also correlated significantly with depression and anxiety. For males, victimisation from controlling behaviours correlated significantly with anxiety. Respondents who had been victimised more than average from physical punishment scored significantly higher than others on victimisation from controlling behaviours, intimate partner physical aggression, depression, and anxiety. Conclusions: It was concluded that victimisation from intimate partner aggression was associated with previous victimisation from physical punishment during childhood and could therefore constitute a form of revictimisation. Key Words: Controlling behaviours by a partner, physical intimate partner aggression, physical punishment during childhood, depression, anxiety, South Africa. -

Online Hate Speech

Measuring trends in online hate speech victimisation Summary of findings and exposure, and attitudes • Overall, 15% of New Zealand adults reported having been personally targeted in New Zealand with online hate speech in the last 12 months. Prepared by Dr. Edgar Pacheco & Neil Melhuish • Compared to our 2018 survey, this result is What is this about? higher by 4 percentage points. On 15 March 2019 a devastating terrorist attack • Over one third of personal experiences of against the Al-Noor Mosque and the Linwood online hate speech occurred after the Christchurch attacks. Islamic Centre in Christchurch killed 51 people and injured 49, some seriously. In addition to • Half of Muslim respondents said they were the tragic loss of life, the attack generated one personally targeted with online hate in the last 12 months. Prevalence was also more of the most significant online safety challenges common among Hindus. New Zealand has experienced. In the immediate aftermath a text reportedly written by • Similar to 2018, people with disabilities and the attacker that included racist and identifiying as non-heterosexuals were also targeted at higher rates. discriminatory language and a livestream video of the attack went viral and continued to • About 3 in 10 adult New Zealanders say reverberate across the internet. they have seen or encountered online hate speech content that targeted someone About 46 minutes after the attack began, else. Netsafe received its first call from the public • Nearly 7 in 10 New Zealand adults think about this content being accessible online. It that online hate speech is spreading. went onto receive just under 600 enquiries and • Over 8 in 10 adults believe that social complaints in the days following.