Fostering Employment for People with Intellectual Disability: the Evidence to Date

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil War Pensions

- - - -- Volume 52 Fall 2000 Number 1 BEFOREDISABILITY CIVIL RIGHTS: CIVIL WARPENSIONS AND THE POL~TICSOF DISABILITY IN AMERICA Peter avid ~lanck* Michael Millender** The tenth anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act ("ADA") has been a bittersweet event for the scholars and activists who have used the occasion to take stock of the statute's impact on the lives of disabled Americans. On the one hand, they have celebrated the fact that the ADA is quietly transforming the nation's built environment and prompting employers to make workplace accommodations that have enabled disabled persons to join, or remain in, the workforce.' On the other hand, they have noted the discouraging judicial reception of the ADA, which has resulted in defendant victories in over ninety percent of . Professor of Law, of Occupational Medicine, and of Psychology at the University of Iowa, and Director of the Law, Health Policy, and Disability Center at the Iowa College of Law; PLD., Psychology, Harvard University; J.D., Stanford Law School. The research on the lives of the Civil War veterans would not have been possible without the generous assistance of Dr. Rob- ert Fogel and his colleagues at the University of Chicago. Michael Stein and Peter Viechnicki provided most helpful comments on earlier versions of this Article. Special thanks to Barbara Broffitt and Michal Schroeder for invaluable research support. The program of research described herein is supported, in part, by grants from The University of Iowa College of Law Foundation; the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, U.S. Department of Education; and" The Great Plains Disability and Technical Assistance Center. -

Disability Studies 1

Disability Studies 1 DST:1101 Introduction to Disability Studies 3 s.h. Introduction and overview of important topics and discussions Disability Studies that pertain to the experience of being disabled; contrast between medical and social models of disability; focus on Chair, Department of Health and Human how disability has been constructed historically, socially, and Physiology politically in an effort to distinguish myth and stigma from • Warren G. Darling reality; perspective that disability is part of human experience and touches everyone; interdisciplinary with many academic Coordinator, Disability Studies areas that offer narratives about experience of disability. GE: • Kristina M. Gordon (Health and Human Physiology) Diversity and Inclusion. DST:1200 Disabilities and Inclusion in Writing and Film Undergraduate certificate: disability studies Around the World 3 s.h. Website: https://clas.uiowa.edu/hhp/undergraduate/ Exploration of human experiences of dis/ability and exclusion/ disability-studies-certificate inclusion. Taught in English. GE: Diversity and Inclusion. Same Disability studies examines disability as a social, cultural, as GHS:1200, GRMN:1200, WLLC:1200. historical, and political phenomenon rather than focusing DST:3102 Culture and Community in Human on its clinical, medical, or therapeutic aspects. It is an Services 2-3 s.h. interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary field that draws on Influence of social issues (e.g., diversity, equity) on human scholarship from diverse disciplines, including anthropology, services; -

The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted Finding New Support for Embodied and Imagined Differences in Contemporary Art

The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted Finding New Support for Embodied and Imagined Differences in Contemporary Art Amanda Cachia Independent scholar and PhD candidate The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted This article undertakes analyses of the contemporary American artists Robert Gober and Cindy Sherman to argue that they use the tropes of the obscene, abject, and traumatic—as discussed by Hal Foster—to make literal and metaphorical reference to David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder’s narrative prosthesis and its “truth,” while simultaneously leaving out the lived experience of disability. Consideration is given to the works of artists Carmen Papalia and Mike Parr, who use complex embodiment as a new methodology to signify empowerment and agency over what we might previously have considered the obscene, abject, or traumatic. They transform traditional understandings of the “prosthetic” within the specific rhetoric of disability. Introduction Why is it so de rigueur for contemporary artists to use disabled embodiment as a means to convey troubled emotional states, as a narrative and literal prosthesis? Narrative prosthesis is a term originally developed by David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, where the disabled body is often inserted into literary, or in this case, visual narratives as a metaphorical opportunity. The disabled body or character is used as a type of crutch or supporting device that allows the narrative to take a turn or a new direction, but often the relationship between the story itself and the disabled body is one based on exploi- tation. “Through the corporeal metaphor,” Mitchell and Snyder articulate, “the disabled or otherwise different body may easily become a stand-in for more abstract notions of the human condition, as universal or nationally specific; thus the textual (disembodied) project depends upon—and takes advantage of—the materiality of the body” (50). -

Appendix K: the Disability Support Pension

K The disability support pension Chapter 6 sets out some options for reform of the DSP given the introduction of the NDIS and NIIS. The desirability and form of change needs to take account of: • the trends in the uptake of the DSP, why these have occurred and what they might mean for policy • the current and impending policy environment and their effects. This appendix examines these issues, as background to the more schematic discussion in the main report. K.1 Background to the DSP Many people with a disability receive their principal income from income support payments, mainly the DSP. Around 800 000 Australians received the DSP in June 2010 at a cost to taxpayers of $11.6 billion in 2009-10. The projected cost is nearly $13.3 billion in 2010-11 and $13.9 billion in 2011-12 (box K.1). The DSP represents the largest income support payment aimed at working age people in Australia and has shifted from around one third of such payments to one half in the decade from 2001-02 (figure K.1). People on DSP are highly disengaged from the labour market. While DSP recipients are permitted to work and to retain at least some benefits, around 90 per cent do not get any income from employment. The share searching for a job is even smaller, with 0.8 per cent of the stock of people on the DSP (or around 6600 people) using Job Services Australia in March 2011.1 1 Centrelink and JSA customer populations from the DEEWR website. -

The Americans with Disabilities Act As Welfare Reform

William & Mary Law Review Volume 44 (2002-2003) Issue 3 Disability and Identity Conference Article 3 February 2003 The Americans with Disabilities Act as Welfare Reform Samuel R. Bagenstos Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Disability Law Commons Repository Citation Samuel R. Bagenstos, The Americans with Disabilities Act as Welfare Reform, 44 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 921 (2003), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol44/iss3/3 Copyright c 2003 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT AS WELFARE REFORM SAMUEL R. BAGENSTOS* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................... 923 I. THE CRITIQUE: BETRAYING THE PROMISES OF THE ADA? ... 930 A. The Definition of "Disability ..................... 930 B. JudicialEstoppel Cases ........................... 936 1. The Basic Problem ............................. 936 2. The Cleveland Decision ......................... 941 3. The Cleveland Aftermath ........................ 943 4. The Critique .................................. 948 C. ReasonableAccommodation Cases .................. 949 II. THE ADA AND THE WELFARE REFORM ARGUMENT ........ 953 A. The Welfare Reform Argument and the ADA .......... 957 1. Early Signs: The Commission on Civil Rights and National Council on the HandicappedReports... 958 2. The Welfare Reform Argument in the Congressional Hearings:Members of Congress Build the Case ...... 960 * Assistant Professor of Law, Harvard Law School. Betsy Bartholet, Matthew Diller, Christine Jolls, Gillian Metzger, Frank Michelman, Martha Minow, Richard Parker, Bill Stuntz, David Westfall, Lucie White, and, as always, Margo Schlanger, offered very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this Article. Thanks to Lizzie Berkowitz, Carrie Griffin, Scott Michelman, Nate Oman, and Lindsay Freeman Wiley for their excellent research assistance. -

Social Protection and Social Security (Including Social Protection Floors)

TRANSLATION---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Guiding Questions for Defining the Normative Content of the Issues Examined at the Tenth Working Session of the Open-ended Working Group: Social Protection and Social Security (including social protection floors) Definition 1. What is the definition of the right to social security and social protection (including social protection floors) for older persons in the national legislation in your country? Or how should such a right be defined, considering existing national, regional and international legal framework? ¿Cuál es la definición del derecho a la seguridad social y la protección social (incluidos los pisos de protección social) para las personas mayores en la legislación nacional de su país? ¿O cómo debería definirse dicho derecho, considerando el marco legal nacional, regional e internacional existente? The right to social security is recognized in various international law instruments that are enshrined in the constitution in Argentina. In the Argentine Constitution, the right to social security is defined as a comprehensive, inalienable right and as a benefit that must be guaranteed by the State. According to the definition in the Inter-American Convention on Protecting the Human Rights of Older Persons (CIPDHPM), ratified by Argentina, the right to social security is a right that must be afforded to older persons in order for them to lead a decent life. Scope of the right 2. What are the key normative elements of the right to social protection and social security for older persons? Please provide references to existing standards on such elements as below, as well as any additional elements: ¿Cuáles son los elementos normativos clave del derecho a la protección social y la seguridad social para las personas mayores? Proporcione referencias a las normas existentes sobre los elementos que se detallan a continuación, así como sobre cualquier elemento adicional: a) Availability of contributory and non-contributory schemes for older persons. -

Revised Proof

Housing Policy in Australia “Australia has avoided a recession in its economic system for nigh on 30 years. Good management our political leaders claim. But Australia’s housing system has failed throughout this time: homelessness has risen; insecure and unaffordable rental are common-place; the over-valuing of homeownership has escalated; and a massive shortage of social and affordable housing has been allowed to develop. How is such neglect or mismanagement of Australians’ housing dreams possible? This book explains why and what to do about it. Pawson, Milligan and Yates carefully document compelling evidence on these issues to provide a contemporary and robust analysis of the when, where, how and why of housing problems in Australia. Moreover, the authors provide the policy solutions and actions to be taken by Federal, State and local governments, as well as the development, fnance and property management industries. Pawson, Milligan and Yates are Australia’s foremostPROOF housing analysts. This book is essential reading for anyone with an interest or a care in reforming Australia’s housing system to be once again ft for all Australians.” —Ian Winter, Housing consultant, and Director, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute 2000–17 “Housing policy and housing systems are rapidly changing and profoundly reshaping access to affordable and high quality housing across all Australia’s cities and regions. Housing Policy in Australia superbly harnesses international evidence and more than two decades of experience to not only analyse but also provide potential solutions to the current housing policy impasse. The book’s comprehen- sive canvassing of housing system diversity—tenures, social differentiation, histor- ical trends—will become necessary reading for housing practitioners and students. -

Invasive Meningococcal Disease (IMD) an Update on Prevention in Australia Prof Robert Booy, NCIRS

Invasive Meningococcal Disease (IMD) An update on prevention in Australia Prof Robert Booy, NCIRS Declaration of interests: RB consults to vaccine companies but does not accept personal payment Invasive Meningococcal Disease Caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis1 • Meningococci are classified into serogroups that are determined by the components of the polysaccharide capsule1 • Globally, 6 serogroups most commonly cause disease2 A B C W X Y • In Australia, three serogroups cause the majority of IMD3 B W Y Cross-section of N. meningitidis bacterial cell wall (adapted from Rosenstein et al)4 1. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). The Australian Immunisation Handbook 10th Edition (2018 update) . Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2018 [Accessed September 2018] 2. Meningococcal meningitis factsheet No 141. World Health Organization website. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs141/en/ [Accessed February 2017] 3. Lahra and Enriquez. Commun Dis Intell 2016; 40 (4):E503-E511 4. Rosenstein NE, et al. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344:1378-1388 Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) in Australia • Overall, the national incidence of invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) in Australia is low • From 2003 to 2013, there was a large decrease in the number AUS notifications: 99% drop in Men C! - after the introduction of 2003 meningococcal C (Men C) dose at 12 months to National Immunisation Program (NIP) – catch-up vacc’n 2-19 year olds (herd immunity <1 & >20yrs) • & reduced smoking +improved SES: 55% drop in Men B! Without a vaccine program • However, in recent years the rate of IMD has increased: 2017 had the highest rate in 10 years • Men W and Y now important in older adults Notifications of invasive meningococcal disease, Australia, 1992- 2017, by year, all serogroups 2013-2017: 4 yrs 3rd Age peak 60-64 yrs W and Y 2017:2018: 383281 cases Highest2019: number? fewer of cases since 2006 Nat’l Men C program from 2003 Adapted from National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System1 1. -

Long-Term Disability Programs in Selected Countries by Ilene R

Long-Term Disability Programs in Selected Countries by Ilene R. Zeitzer and Laurel E. Beedon* In 1985, the Social Security Administration commis- sioned an 18-month research project to study disability in eight industrialized countries: Austria, Canada, Finland, the Federal Republic of Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The study focused on three key areas: (1) the initial determination of disability, (2) the methods of monitoring disability, and (3) the incen- tives to return to work. Although the study revealed great variations among the countries in the definition of long- term disability, the approach followed in providing benefits, and the organization and features of the pro- grams, some basic similiarities were also found. Among the similarities are: (1) most countries have several income- maintenance programs to protect workers in the event that they are disabled, and (2) the disability test to determine whether a person is eligible for a disability benefit is am- biguous in that the various programs each have different eligibility criteria, different definitions of disability, differ- ent considerations given to labor-market conditions, and so forth. This article examines the diversity among the coun- tries and attempts to highlight unique approaches to ad- judicating disability, providing linkages to rehabilitation, and creating incentives for returning to work. This article compares key features of social security Overview long-term disability programs in eight industrialized countries.’ The countries whose program features are Most of the countries in the study have three public surveyed are: Austria, Canada, Finland, the Federal income-maintenance programs to protect workers in Republic of Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, case of disability. -

Annual-Report-2017-Web.Pdf

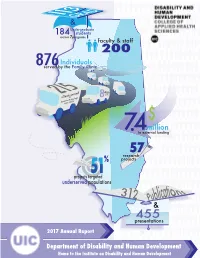

GRAD & Undergraduate 184 students across 7programs faculty & staff 200 Individuals 876served by the Family Clinic Clientsby served Assistive Technology Units (ATUs) $ million 7.4In external funding research57 % projects projects targeted51 underserved populations 2 E.Kief 2017 & 455 presentations 2017 Annual Report Department of Disability and Human Development Home to the Institute on Disability and Human Development Table of Contents 3 - Post-Doctoral Program Trains Tomorrow’s Leaders 4 - PhD Students Expand their Horizons Internationally 5 - First Undergraduate Student Graduates from DHD’s Major 6 - IL LEND Trainees Learn by Doing 7 - DHD Promotes Systems Change Through Training and Advocacy 8 - DHD Awards Three Trainees Diversity Fellows 9 - DHD Alumni as Leaders in Policy and Practice 10 - Assistive Technology Unit Promotes Independence for People with Disabilities 11 - Family Clinic Provides Community Based Programs 12 - Faculty Committed to Scholarship and Activism 13 - RRTCDD Promotes the Health of People with IDD 14 - Continuing the Legacy of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by Bridging Research, Training, and Education 15 - Students Recognized for their Achievements Welcome Statement We are pleased to present the 2016-2017 Annual Report for the Department of Disability and Human Development (DHD) and its Institute on Disability and Human Development (IDHD). It has been an exciting year for DHD as we now offer a full range of academic programs, from an undergraduate minor and major to a PhD program in Disability Studies and graduate certificates in Assistive Technology or Disability Ethics. We are attracting over 600 students to our courses each semester. Additionally, we are now able to offer teaching assistantships to our doctoral students. -

Disability and Aging: Historical and Contemporary Challenges William N

Marquette Elder's Advisor Volume 11 Article 4 Issue 1 Fall Disability and Aging: Historical and Contemporary Challenges William N. Myhill Peter Blanck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/elders Part of the Elder Law Commons Repository Citation Myhill, William N. and Blanck, Peter (2009) "Disability and Aging: Historical and Contemporary Challenges," Marquette Elder's Advisor: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/elders/vol11/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Elder's Advisor by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISABILITY AND AGING: HISTORICAL AND CONTEMPORARY CHALLENGES William N. Myhill and Peter Blanck* INTRODUCTION Older Americans and Americans with disabilities face challenges actively participating in the workforce and community, living independently, and aging in place.' The proportion of older adults in the U.S. population is growing rapidly. 2 Similarly, individuals with life-long or existing * William N. Myhill, M.Ed., J.D., Director of Legal Research & Writing, Burton Blatt Institute (BBI), Adjunct Professor (College of Law) & Faculty Associate, Center for Digital Literacy (iSchool), Syracuse University; Peter Blanck, Ph.D., J.D., University Professor & Chairman BBI, Syracuse University. The program of research described herein is supported, in part, by grants from: (a) the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), U.S. Department of Education, as follows (i) "Demand Side Employment Placement Models," Grant No. -

Persons with Disabilities Act, 2011 Working Draft (9

Persons with Disabilities Act, 2011 Working Draft (9th February, 2011 version) Prepared by Centre for Disability Studies NALSAR University of Law Hyderabad, India 1 INDEX Contents Page Nos Objects and Reasons Preamble Part I: Introductory • Extent • Enforcement • Purpose • Definitions • Guiding Principles for Implementation and Interpretation Part II: Lifting the Barriers • Awareness Raising • Accessibility • Human Resource Development • Equality and Non discrimination • Pro-active Interventions for Persons with Disability with increased vulnerability. • Women with Disabilities • Children with Disabilities Part III: Legal Capacity and Civil and Political Rights • Right to Equal Recognition before the Law • Right to life • Situations of Risk and Humanitarian Emergencies • Right to Liberty • Access to Justice • Right to Integrity • Right to be Protected against Violence Abuse and Exploitation • Right to Privacy • Freedom of Speech and Expression • Right to Live Independently and in the Community • Right to Home and Family • Right to Exercise Franchise, Stand for Election and Hold Public Office 2 Part IV: Capability Development • Programmatic Entitlements and definition of Persons with Disability • Education • Employment Work Occupation • Social Security • Health • Habilitation and Rehabilitation • Leisure Culture and Sport Part V: Regulatory and Adjudicative Authorities • Disability Rights Authority • Court of the National Disability Commissioners • State Disability Courts Part VI: Offences and Penalties Part VII: Miscellaneous • Power to make rules • Power to make regulations 3 The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2011 Statement of Objects and Reasons India has ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD) and has undertaken the obligation to ensure and promote the full realization of all human rights and fundamental freedoms for all Persons with Disabilities without discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability.