Theorizing the Research Divide Between Special Education and Mathematics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disability Studies 1

Disability Studies 1 DST:1101 Introduction to Disability Studies 3 s.h. Introduction and overview of important topics and discussions Disability Studies that pertain to the experience of being disabled; contrast between medical and social models of disability; focus on Chair, Department of Health and Human how disability has been constructed historically, socially, and Physiology politically in an effort to distinguish myth and stigma from • Warren G. Darling reality; perspective that disability is part of human experience and touches everyone; interdisciplinary with many academic Coordinator, Disability Studies areas that offer narratives about experience of disability. GE: • Kristina M. Gordon (Health and Human Physiology) Diversity and Inclusion. DST:1200 Disabilities and Inclusion in Writing and Film Undergraduate certificate: disability studies Around the World 3 s.h. Website: https://clas.uiowa.edu/hhp/undergraduate/ Exploration of human experiences of dis/ability and exclusion/ disability-studies-certificate inclusion. Taught in English. GE: Diversity and Inclusion. Same Disability studies examines disability as a social, cultural, as GHS:1200, GRMN:1200, WLLC:1200. historical, and political phenomenon rather than focusing DST:3102 Culture and Community in Human on its clinical, medical, or therapeutic aspects. It is an Services 2-3 s.h. interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary field that draws on Influence of social issues (e.g., diversity, equity) on human scholarship from diverse disciplines, including anthropology, services; -

The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted Finding New Support for Embodied and Imagined Differences in Contemporary Art

The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted Finding New Support for Embodied and Imagined Differences in Contemporary Art Amanda Cachia Independent scholar and PhD candidate The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted This article undertakes analyses of the contemporary American artists Robert Gober and Cindy Sherman to argue that they use the tropes of the obscene, abject, and traumatic—as discussed by Hal Foster—to make literal and metaphorical reference to David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder’s narrative prosthesis and its “truth,” while simultaneously leaving out the lived experience of disability. Consideration is given to the works of artists Carmen Papalia and Mike Parr, who use complex embodiment as a new methodology to signify empowerment and agency over what we might previously have considered the obscene, abject, or traumatic. They transform traditional understandings of the “prosthetic” within the specific rhetoric of disability. Introduction Why is it so de rigueur for contemporary artists to use disabled embodiment as a means to convey troubled emotional states, as a narrative and literal prosthesis? Narrative prosthesis is a term originally developed by David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, where the disabled body is often inserted into literary, or in this case, visual narratives as a metaphorical opportunity. The disabled body or character is used as a type of crutch or supporting device that allows the narrative to take a turn or a new direction, but often the relationship between the story itself and the disabled body is one based on exploi- tation. “Through the corporeal metaphor,” Mitchell and Snyder articulate, “the disabled or otherwise different body may easily become a stand-in for more abstract notions of the human condition, as universal or nationally specific; thus the textual (disembodied) project depends upon—and takes advantage of—the materiality of the body” (50). -

Fostering Employment for People with Intellectual Disability: the Evidence to Date

Fostering employment for people with intellectual disability: the evidence to date Erin Wilson and Robert Campain August 2020 This document has been prepared by the Centre for Social Impact Swinburne for Inclusion Australia as part of the ‘Employment First’ project, funded by the National Disability Insurance Agency. ‘ About this report This report presents a set of ‘evidence pieces’ commissioned by Inclusion Australia to inform the creation of a website developed by Inclusion Australia as part of the ‘Employment First’ (E1) project. Suggested citation Wilson, E. & Campain, R. (2020). Fostering employment for people with intellectual disability: the evidence to date, Hawthorn, Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology. Research team The research project was undertaken by the Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology, under the leadership of Professor Erin Wilson together with Dr Robert Campain. The research team would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ms Jenny Crosbie, Dr Joanne Qian, Ms Aurora Elmes, Dr Andrew Joyce and Mr James Kelly (of the Centre for Social Impact) and Dr Kevin Murfitt (Deakin University) who have collaborated in the sharing of information and analysis regarding a range of research related to the employment of people with a disability. Page 2 ‘ Contents Background 5 About the research design 6 Structure of this report 7 Synthesis: How can employment of people with intellectual disability be fostered? 8 Evidence piece 1: Factors positively influencing the employment of people -

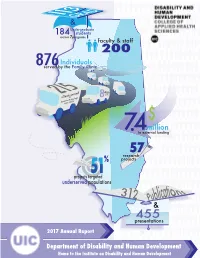

Annual-Report-2017-Web.Pdf

GRAD & Undergraduate 184 students across 7programs faculty & staff 200 Individuals 876served by the Family Clinic Clientsby served Assistive Technology Units (ATUs) $ million 7.4In external funding research57 % projects projects targeted51 underserved populations 2 E.Kief 2017 & 455 presentations 2017 Annual Report Department of Disability and Human Development Home to the Institute on Disability and Human Development Table of Contents 3 - Post-Doctoral Program Trains Tomorrow’s Leaders 4 - PhD Students Expand their Horizons Internationally 5 - First Undergraduate Student Graduates from DHD’s Major 6 - IL LEND Trainees Learn by Doing 7 - DHD Promotes Systems Change Through Training and Advocacy 8 - DHD Awards Three Trainees Diversity Fellows 9 - DHD Alumni as Leaders in Policy and Practice 10 - Assistive Technology Unit Promotes Independence for People with Disabilities 11 - Family Clinic Provides Community Based Programs 12 - Faculty Committed to Scholarship and Activism 13 - RRTCDD Promotes the Health of People with IDD 14 - Continuing the Legacy of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by Bridging Research, Training, and Education 15 - Students Recognized for their Achievements Welcome Statement We are pleased to present the 2016-2017 Annual Report for the Department of Disability and Human Development (DHD) and its Institute on Disability and Human Development (IDHD). It has been an exciting year for DHD as we now offer a full range of academic programs, from an undergraduate minor and major to a PhD program in Disability Studies and graduate certificates in Assistive Technology or Disability Ethics. We are attracting over 600 students to our courses each semester. Additionally, we are now able to offer teaching assistantships to our doctoral students. -

The Disabled People's Movement

The Disabled People’s Movement Book Four A Resource Pack for Local Groups of Disabled People Published by the BCODP The publication of this booklet was made possible by a grant from Charity Projects. First published in 1997 by The British Council of Organisations of Disabled People (BCODP). © BCODP All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publishers and copyright owners except for the quotation of brief passages by reviewers for the public press. Composed by Equal Ability for BCODP Printed by Bailey & Sons Ltd., Somercotes, Derbyshire About this booklet This booklet will not tell you how to run your group, or how to do things. It is designed to signpost you to the information that you need. It will: - Give you ideas about areas you need to think about - Point you in the direction of books and organisations that may help. Some of these books will tell you how to do things. - Fill-in some of the gaps that these books leave about being a group of disabled people. While we were working on these booklets, we talked to many local groups of disabled people. They told us about the hard work and determination you need to succeed. This Resource Pack has been written to help you find support and information so that your hard work does not go to waste. We hope that you will find these signposts get you where you want to go a bit more quickly than you would get there without them! Full details of all books and reference materials mentioned in this booklet is contained in Resource Booklet 6 Introduction What this booklet covers This booklet covers the Disabled People's Movement: • Disability and the Disabled People's Movement • The History of the Movement • International Issues • Integration and inclusion • Campaigning • Self-organisation • BCODP There are some good books that will help you understand more about these subjects. -

Modern Prejudice Towards Disabled People Carli Friedman, Phd Council on Quality and Leadership

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Volume 14 REVIEW OF DISABILITY STUDIES: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL Issue 4 Research Article Aversive Ableism: Modern Prejudice Towards Disabled People Carli Friedman, PhD Council on Quality and Leadership Abstract: The aim of this study was to examine the patterns of explicit (conscious) and implicit (unconscious) disability prejudice. The majority of participants were implicitly prejudiced against disabled people despite having low explicit prejudice. This pattern is in alignment with aversive ableism — disability prejudice was present among those who meant well. Keywords: aversive ableism; prejudice; ableism Unlike the historically prominent medical model of disability that frames disability as an individualized problem one “suffers” from and needs treatment for (Linton, 1998), the ideological shift to the social model conceptualizes disability as something that is socially constructed—a form of social oppression. Under this model, Barnes and Mercer (2003) “conceptualize disability as a form of social oppression akin to sexism and racism, although it exhibits a distinctive form, with its own dynamics…as a historically and culturally specific form of social oppression” (p. 18). Abberley (1987) also argues that the social model or social theory of disability is strongest when it is based on the concept of oppression. Abberley discusses oppression as socially created disadvantages that are placed upon disabled people. This includes the recognition of the social origins of impairment, and opposition to the economic, social, environmental, and psychological disadvantages imposed on disabled people. Systemic discrimination, which is rooted in history, constitutes a significant amount of the oppression disabled people face. -

Governing the Voice: a Critical History of Speech-Language Pathology

© Joshua & Charis St. Pierre DOI: https://doi.org/10.22439/fs.v0i24.5530 ISSN: 1832-5203 Foucault Studies, No. 24, pp. 151-184, June 2018 Governing the Voice: A Critical History of Speech-Language Pathology Joshua St. Pierre, University of Alberta Charis St. Pierre, Independent Scholar Abstract: This essay argues that Speech-Language Pathology (SLP) emerged as a response to the early twentieth-century demand for docile, efficient, and thus productive speech. As the capacity of speech became more central to the industrial and democratic operations of modern society, an apparatus was needed to bring speech under the fold of biopower. Beyond simple economic productivity, the importance of SLP lies in opening the speaking subject up to management and normalization— creating, in short, biopolitical subjects of communication. We argue that SLP accordingly emerged not as a discreet institution, but as a set of practices which can be clustered under three headings: calculating deviance, disciplining the tongue, and speaking the truth of pathologized subjects. Keywords: speech; communication; disability; speech-language pathology; genealogy The therapeutic industry of Speech-Language Pathology (SLP) has become the dominant mode of approaching speech variation. The way we understand voices that stray beyond codified linguistic and temporal boundaries is widely assumed to be medical and scientific, not political. Part of this depoliticization stems from the fact that expert knowledges of speech disability have gone uncontested. This paper thus traces the emergence of SLP in the early twentieth century and argues that it be read alongside the increasing centrality of communicative networks within modern society and the need for a corresponding apparatus to govern speech. -

Disability Studies - Enabling Equality

Rembis; Yes We Can Change 19 Yes We Can Change: Disability Studies - Enabling Equality Michael A. Rembis, Ph.D. University at Buffalo Abstract In this article, I offer a brief assessment of the international disability rights and culture movements and disability studies, as well as a commentary on the future of disability and disability studies. A diverse group of activists, artists, and scholars have brought about momentous legal changes in dozens of countries around the world. They have also enabled a critical rearticulation of what it means to be disabled. Yet, this revisioning of disability and this repositioning of disabled people remains fraught. I contend that while movement participants, scholars, and their allies are off to a great start, they have yet to grapple in any serious way with some of the most important and contentious issues within the disability rights and culture movements and disability studies, namely their own internal diversity and the material reality of many disabled peoples’ lives. Despite these complexities, I maintain that the disability rights and culture movements and disability studies have tremendous transformative potential. We are living at a critical moment of history. The monolith), we recognized that we, the disabled, had ar- election of Barack Obama as the 44th President of the rived socially and politically. Or had we? United States on November 4, 2008 was greeted the In this article, I will offer a brief assessment of the world over with a potent mixture of unrestrained joy recent past and a commentary on the future of disability and hope by those individuals, groups, and organiza- and disability studies. -

Everyday Ableism Notes

Everyday Ableism Amanda Kraus, Ph. D. Historical Oppression of Disabled People [Table] Belief Manifestation Treatment Possessed Danger to self and others Exploitation Immoral/Sinner Contagious Experimentation Defective Incapable of independence Sterilization Institutionalization [End Table] Re/Framing Disability [Table] Prevalent Emerging Due to a physiological difference, diagnosis, The environment disables people with injury or impairment, individual is at a deficit, impairments by its design. must be cured or pitied. The individual is the problem. The environment is the problem. Disabled by impairment. Disabled by design. Access is individual – medical, charity, legal. Access is a right, not a special need. Dominant narrative Disability Studies [End Table] Language, media and design reflect and perpetuate ableism, impacts higher education. “Disability” Language • disABILITY • Special needs • Differently-abled • Handicapable • Physically-challenged • Confined to a chair, wheelchair-bound • The disabled, the blind, the deaf, • Suffers from… • Person-first language Implications: Person-first and Identity-first Language Person-first: • I am a person with a disability. • Distances person from disability. • I am separate from what you think disability is. Identity-first: • I am a disabled person. • Reflects social model – disabled by environments, attitudes, etc. • Consistent with disability studies and many disabled activists and leaders. Media Representation - Helpless v Heroic Helpless • Fear • Angry • Jokes • Charity Heroic • Supercrip -

Disability Studies (DST) 1

Disability Studies (DST) 1 DST 375. (Dis)Ability Allies: To be or not to be? Developing Identity Disability Studies (DST) and Pride from Practice. (3) Explores what it means to be ally to/in/with the disability community DST 102. Beginning ASL II. (4) in America. The course emphasizes identity formation and how that The Beginning II course is a continuation of the Beginning ASL I formation can inform the construction of the ally identity. Through course. This course will continue to introduce conversationally deconstructing learned values, knowledge, and images of disability relevant signs, grammatical principles, and background information that mitigate ally behavior, students discover the micro and macro related to the Deaf culture with the objective of teaching students structures that support ally behavior. By exploring how social control to sign and understand ASL with an increasing ability at the ACTFL and social change have worked in other civil rights movements, proficiency intermediate low-mid level (Swender, Conrad, & Vicars, students understand the necessity of identifying and including allies 2012). Swender, E., Conrad, D. J., & Vicars, R. (2012). ACTFL proficiency in the disability movement for civil rights. IC. CAS-C. guidelines 2012. ACTFL, INC. Cross-listed with EDP/SOC/WGS. Prerequisite: DST/SPA 101 or SPA 248. DST 377. Independent Studies. (0-6) Cross-listed with SPA 102. DST 378. Media Illusions: Creations of "The Disabled" Identity. (3) DST 169. Disability and Literature. (3) (MPF) Provides a critical analysis of past -

Introducing Disability Studies

EXCERPTED FROM Introducing Disability Studies Ronald J. Berger Copyright © 2013 ISBNs: 978-1-58826-866-2 hc 978-1-58826-891-4 pb 1800 30th Street, Ste. 314 Boulder, CO 80301 USA telephone 303.444.6684 fax 303.444.0824 This excerpt was downloaded from the Lynne Rienner Publishers website www.rienner.com Contents Preface ix 1 Disability in Society 1 Speaking About Disability 5 Defining Disability and the Subject Matter of Disability Studies 6 The Disability Rights Movement 15 2 Explaining Disability 25 Beyond the Medical Model 26 Disability Culture and Identity 30 The Political Economy of Disability 34 Insights from Feminist and Queer Theory 37 Disability and Symbolic Interaction 43 3 History and Law 51 Preliterate, Ancient, and Medieval Societies 51 The Uneven March of Progress 55 Rehabilitation and Reform 62 The Contribution of Franklin Delano Roosevelt 65 The Politics of the ADA 69 The Legal Aftermath of the ADA 72 4 The Family and Childhood 79 Parental First Encounters with Childhood Disability 81 Measuring Up to the Norm 89 The Child’s Perspective 93 vii viii Contents Impact on Family Life 99 The Dilemmas of Special Education 104 5 Adolescence and Adulthood 113 The Trials and Tribulations of Adolescence 113 The Transition to Adulthood 123 The World of Work 128 Sexual and Emotional Intimacy 132 Health Care and Personal Assistance 137 6 The Bodily Experience of Disability 145 Perceiving the World Without Sight or Sound 146 The Phenomenology of Sign Language 154 Navigating the Physical Environment with a Mobility Impairment 156 Recovery -

Disability, Work and Welfare Colin Barnes

1 Disability, Work and Welfare Colin Barnes (This is a penultimate draft of a paper that appeared in the academic journal Sociology Compass, 6 (6), pp. 472-484 (2012)). Abstract: There is a wealth of evidence that disabled people experience far higher levels of unemployment and underemployment than non-disabled peers. Yet hitherto sociologists have paid scant attention to the structural causes of this issue. Drawing on a socio/political or social model of disability perspective this paper argues for a reconfiguration of the meaning of disability and work in order to address this problem. It is also suggested that such a strategy will make a significant contribution to the struggle for a fairer and equitable global society. Key words: Disability, Employment, Social model, Theory, Work 2 Re-thinking Disability, Work and Welfare Colin Barnes Introduction Over recent decades, the systematic exclusion of people labelled ‘disabled’ from mainstream society has attracted increasing policy attention within and across nation states. The general response has been policies clustered around notions of ‘care’ and social welfare with additional schemes to get disabled people into paid work. But whilst there has been some improvement in the employment situation for disabled individuals in parts of the world, in most countries unemployment, poverty and dependence are common experiences for the overwhelming majority of people with impairments (Barron and Ncube, 2010). Around 2-3 percent of impairments are present at birth while the remainder are acquired during the life course (2001a; Priestley, 2003). Indeed, recent estimates suggest that more than a billion people (around 15 per cent of the global population) experience ‘disability’ (WHO, 2011).