Life in Inclusive Classrooms: Storytelling with Disability Studies in Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Assistance Paper

State Board of Education Pam StewartStewart Commissioner of of Education Education Marva Johnson, Chair John R. Padget, Vice Chair Members Gary Chartrand Tom Grady Rebecca Fishman Lipsey Michael Olenick Andy Tuck DPS: 2016-13 Date: January 15, 2016 Technical Assistance Paper Least Restrictive Environment Considerations Related to Individual Educational Plans Summary: This technical assistance paper (TAP) updates previous technical assistance provided to school districts regarding the provision of services for students with disabilities in the least restrictive environment (LRE). Individual educational plan (IEP) teams must adhere to all legal requirements related to placement in the LRE. This TAP will in addition address other considerations that must be addressed when determining the most appropriate placement for a student with a disability. It will also address issues related to service delivery and scheduling methods for students with disabilities. Contact: Jessica Brattain Program Specialist Irgssu ed by the [email protected] 850-245-0475Florida Department of Education Status: X Revises and replacesDivision existing Technical of Public Assistance Schools Paper: 10744Bureau (FY 2000- of Exceptional5): Least Restrictive Education Environment and Student Considerations Services Related to Individual Educationalhttp://www.fldoe.org/ese Plans Issued by the Florida Department of Education Division of Public Schools Bureau of Exceptional Education and Student Services http://www.fldoe.org/ese www.fldoe.org 325 W. Gaines Street | Tallahassee, FL 32399-0400 | 850-245-0505 Table of Contents A. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) Requirements for Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) ........................................................................................... 1 A-1. What does IDEA require related to LRE? .....................................................................1 A-2. What are supplementary aids and services? ...................................................................1 A-3. -

Disability Studies 1

Disability Studies 1 DST:1101 Introduction to Disability Studies 3 s.h. Introduction and overview of important topics and discussions Disability Studies that pertain to the experience of being disabled; contrast between medical and social models of disability; focus on Chair, Department of Health and Human how disability has been constructed historically, socially, and Physiology politically in an effort to distinguish myth and stigma from • Warren G. Darling reality; perspective that disability is part of human experience and touches everyone; interdisciplinary with many academic Coordinator, Disability Studies areas that offer narratives about experience of disability. GE: • Kristina M. Gordon (Health and Human Physiology) Diversity and Inclusion. DST:1200 Disabilities and Inclusion in Writing and Film Undergraduate certificate: disability studies Around the World 3 s.h. Website: https://clas.uiowa.edu/hhp/undergraduate/ Exploration of human experiences of dis/ability and exclusion/ disability-studies-certificate inclusion. Taught in English. GE: Diversity and Inclusion. Same Disability studies examines disability as a social, cultural, as GHS:1200, GRMN:1200, WLLC:1200. historical, and political phenomenon rather than focusing DST:3102 Culture and Community in Human on its clinical, medical, or therapeutic aspects. It is an Services 2-3 s.h. interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary field that draws on Influence of social issues (e.g., diversity, equity) on human scholarship from diverse disciplines, including anthropology, services; -

The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted Finding New Support for Embodied and Imagined Differences in Contemporary Art

The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted Finding New Support for Embodied and Imagined Differences in Contemporary Art Amanda Cachia Independent scholar and PhD candidate The (Narrative) Prosthesis Re-Fitted This article undertakes analyses of the contemporary American artists Robert Gober and Cindy Sherman to argue that they use the tropes of the obscene, abject, and traumatic—as discussed by Hal Foster—to make literal and metaphorical reference to David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder’s narrative prosthesis and its “truth,” while simultaneously leaving out the lived experience of disability. Consideration is given to the works of artists Carmen Papalia and Mike Parr, who use complex embodiment as a new methodology to signify empowerment and agency over what we might previously have considered the obscene, abject, or traumatic. They transform traditional understandings of the “prosthetic” within the specific rhetoric of disability. Introduction Why is it so de rigueur for contemporary artists to use disabled embodiment as a means to convey troubled emotional states, as a narrative and literal prosthesis? Narrative prosthesis is a term originally developed by David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder, where the disabled body is often inserted into literary, or in this case, visual narratives as a metaphorical opportunity. The disabled body or character is used as a type of crutch or supporting device that allows the narrative to take a turn or a new direction, but often the relationship between the story itself and the disabled body is one based on exploi- tation. “Through the corporeal metaphor,” Mitchell and Snyder articulate, “the disabled or otherwise different body may easily become a stand-in for more abstract notions of the human condition, as universal or nationally specific; thus the textual (disembodied) project depends upon—and takes advantage of—the materiality of the body” (50). -

Fostering Employment for People with Intellectual Disability: the Evidence to Date

Fostering employment for people with intellectual disability: the evidence to date Erin Wilson and Robert Campain August 2020 This document has been prepared by the Centre for Social Impact Swinburne for Inclusion Australia as part of the ‘Employment First’ project, funded by the National Disability Insurance Agency. ‘ About this report This report presents a set of ‘evidence pieces’ commissioned by Inclusion Australia to inform the creation of a website developed by Inclusion Australia as part of the ‘Employment First’ (E1) project. Suggested citation Wilson, E. & Campain, R. (2020). Fostering employment for people with intellectual disability: the evidence to date, Hawthorn, Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology. Research team The research project was undertaken by the Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology, under the leadership of Professor Erin Wilson together with Dr Robert Campain. The research team would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ms Jenny Crosbie, Dr Joanne Qian, Ms Aurora Elmes, Dr Andrew Joyce and Mr James Kelly (of the Centre for Social Impact) and Dr Kevin Murfitt (Deakin University) who have collaborated in the sharing of information and analysis regarding a range of research related to the employment of people with a disability. Page 2 ‘ Contents Background 5 About the research design 6 Structure of this report 7 Synthesis: How can employment of people with intellectual disability be fostered? 8 Evidence piece 1: Factors positively influencing the employment of people -

IAC Ch 15, P.1 282—15.2(272) Specific Requirements. for Each Of

IAC Ch 15, p.1 282—15.2(272) Specific requirements. For each of the following teaching endorsements in special education, the applicant must have completed 24 semester hours in special education. 15.2(1) to 15.2(5) Rescinded IAB 7/20/05, effective 8/24/05. 15.2(6) Deaf or hard of hearing. a. Option 1. This endorsement authorizes instruction in programs serving students with hearing loss from birth to age 21 (and to a maximum allowable age in accordance with Iowa Code section 256B.8). An applicant for this option must complete the following requirements and must have completed an approved program in teaching the deaf or hard of hearing from a recognized Iowa or non-Iowa institution and must hold a regular education endorsement. See rules 282—14.140(272) and 282—14.141(272). (1) Foundations of special education. The philosophical, historical and legal bases for special education, including the definitions and etiologies of individuals with disabilities, and including individuals from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. (2) Characteristics of learners. Preparation which includes various etiologies of hearing loss, an overview of current trends in educational programming for students with hearing loss and educational alternatives and related services, and the importance of the multidisciplinary team in providing more appropriate educational programming from birth to age 21. Preparation in the social, emotional and behavioral characteristics of individuals with hearing loss, including the impact of such characteristics on classroom learning. Knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the hearing mechanism and knowledge of the development of secondary senses when hearing is impaired, effect of hearing loss on learning experiences, psychological aspects of hearing loss, and effects of medications on the hearing system. -

1. a Student with a Disability Attends Only Math Class with Students Without Disabilities

__________ 1. A student with a disability attends only math class with students without disabilities. This is an example of: a. Inclusion b. Mainstreaming c. Reintegration d. All of the above __________ 2. What statement best describes “inclusion?” a. A philosophy that brings together diverse families, educators, and institutions to increase belongingness in schools b. A mandate for all students that is supported by special education law c. A system that promotes academic success by grouping students with disabilities in special classrooms d. A program developed by special education teachers designed to improve their working conditions __________ 3. Mainstreaming and inclusion are similar in that both: a. Require students to earn their way into general education b. Mean full-time placement in general education c. Share common goals d. All of the above __________ 4. The Least Restrictive Environment concept: a. Means all students must be placed in general education b. Prevents students from being placed in segregated settings c. Prefers that students attend school as close as possible to their homes d. None of the above __________ 5. Which of the following is not a principle of inclusion? a. All learners have equal access b. All learners are treated the same c. Individual strengths and challenges and diversity d. Community and collaboration __________ 6. Which of the following sequences is consistent with the continuum of educational services from most to least restrictive educational placements for students? a. Full-time special class, special school, residential school b. Full-time special class, part-time special class, general education class with assistance c. -

Annual-Report-2017-Web.Pdf

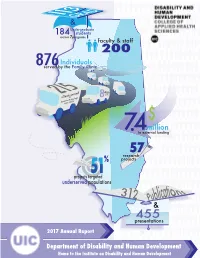

GRAD & Undergraduate 184 students across 7programs faculty & staff 200 Individuals 876served by the Family Clinic Clientsby served Assistive Technology Units (ATUs) $ million 7.4In external funding research57 % projects projects targeted51 underserved populations 2 E.Kief 2017 & 455 presentations 2017 Annual Report Department of Disability and Human Development Home to the Institute on Disability and Human Development Table of Contents 3 - Post-Doctoral Program Trains Tomorrow’s Leaders 4 - PhD Students Expand their Horizons Internationally 5 - First Undergraduate Student Graduates from DHD’s Major 6 - IL LEND Trainees Learn by Doing 7 - DHD Promotes Systems Change Through Training and Advocacy 8 - DHD Awards Three Trainees Diversity Fellows 9 - DHD Alumni as Leaders in Policy and Practice 10 - Assistive Technology Unit Promotes Independence for People with Disabilities 11 - Family Clinic Provides Community Based Programs 12 - Faculty Committed to Scholarship and Activism 13 - RRTCDD Promotes the Health of People with IDD 14 - Continuing the Legacy of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by Bridging Research, Training, and Education 15 - Students Recognized for their Achievements Welcome Statement We are pleased to present the 2016-2017 Annual Report for the Department of Disability and Human Development (DHD) and its Institute on Disability and Human Development (IDHD). It has been an exciting year for DHD as we now offer a full range of academic programs, from an undergraduate minor and major to a PhD program in Disability Studies and graduate certificates in Assistive Technology or Disability Ethics. We are attracting over 600 students to our courses each semester. Additionally, we are now able to offer teaching assistantships to our doctoral students. -

Service Delivery Challenges, Solutions, Options

SERVICE DELIVERY CHALLENGES, SOLUTIONS, OPTIONS GEORGIA SPEECH-LANGUAGE-HEARING ASSOCIATION FEBRUARY 6, 2016 Jean Blosser, CCC-SLP, Ed.D Creative Strategies for Special Education [email protected] – 443-255-5854 www.CSSEconsult.com DISCLOSURES • Financial Financial compensation from GSHA for this presentation Royalties from Plural Publishing and Cengage Publishers President & Education Consultant, Creative Strategies for Special Education. • Non-financial Member, ASHA Committee on Honors Blosser 2 SERVICE DELIVERY IN SCHOOLS Blosser 3 WHAT ARE YOUR OBJECTIVES TODAY? Are you challenged by your complex and diverse workload and caseload? Have you heard about a range of service delivery models but are unsure of how or when to implement them in your program? Do you have questions about dosage for services? Blosser 4 LEARNER OUTCOMES As a result of this course, participants will be able to……………………….. 1. Describe a range of service delivery options and important aspects to consider. 2. Match students with the most appropriate service delivery to meet their needs. 3. Explain service delivery options to parents and teachers for foster buy-in and engagement. 4. Achieve positive outcomes as a result of appropriate services. Blosser 5 AGENDA I. Introduce the topic of service delivery in school-based settings and goals for the session II. Discuss challenges SLPs experience with implementing a range of service delivery options III. Describe a menu of service delivery options IV. Provide tips for matching students with the appropriate dosage and service delivery model V. Recommend strategies and tools for explaining models and options to parents and teachers and getting their buy-in and engagement VI. -

Instructional Assistant - Resource Room

INSTRUCTIONAL ASSISTANT - RESOURCE ROOM Classification: Instructional Assistant – Resource Room Location: Assigned Department Reports to: District Administrator FLSA Status: Non-Exempt Bargaining Unit: OSEA This is a standard position description to be used for instructional assistant positions with similar duties, responsibilities, classification and compensation. Instructional assistants assigned to the position description may or may not perform all of the essential functions indicated in this position description. This job description does not constitute an employment agreement between the employer and employee and is subject to change by the employer as the needs of the employer and requirements of the job change. Part I: Position Summary: The incumbent performs a variety of instructional and/or support duties to assist the school and teachers in instruction, supervision, and education of students with special needs (medical and/or disability) in regular education classroom settings (inclusion), one-on-one, as well as Resource Room pullout. Part II: Supervision and Controls over the Work: Instructional assistants work under the day-to-day direction of the staff member(s) supported, and under the special education teacher assigned responsibility for learning support in a resource room. Teachers and/or educational staff associates provide specific directions and oversight for supervision and/or instructional support for individual students. Instructional Assistants (Resource Room) are responsible for being familiar with the school/district policies and procedures which govern their work, for following the teacher’s direction, and for adhering to the individual student plan. Part III: Major Duties and Responsibilities (depending on specific assignment): 1. Works collaboratively by assisting teachers and specialists in assessment, academic and instructional support, student interactions, enforcing safe behaviors, and enhancing social growth of students in the school setting. -

Special Education Program Descriptions 2016-17

Special Education Student Services Special Education Program Descriptions 2016-17 Bethlehem Central School District 700 Delaware Avenue, Delmar, New York 12054 Introduction This document provides descriptions of the special education programs and services in the Bethlehem Central School District. These descriptions were developed based on the learner characteristics of the students. This allows the district to integrate appropriate supports, professional development, assistive technology and parent supports with each program or type of service. These program descriptions are consistent with the Special Education Principles that were developed in 2004 and form the basis of all of our program planning and services. Bethlehem Central School District Special Education Program Principles . We provide special education services that meet the individual needs of the child, are developmentally appropriate and strength-based. These services are planned in collaboration with all the child-serving systems involved in the child's life and are provided in a supportive learning environment. We recognize that the child’s family is the primary support system for the child and participates in all stages of the decision-making and planning process. We recognize and respect the behavior, ideas, attitudes, values, beliefs, customs, language, rituals, ceremonies and practices characteristic of the child's and family's ethnic group. We will bring special education expertise to the student in the general education learning environment to the greatest extent possible. All instructional staff (administrators, general education teachers, special education teachers, and paraprofessional staff) is supported in developing the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to design learning environments and instruction to meet the needs of diverse learners, including those with significant disabilities. -

NCSD Counseling Handbook

NCSD Counseling Handbook NCSD Counselor Handbook 6.26.18 1 Table of Contents Section Page Number Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 4 NCSD Counseling Vision/Mission .................................................................................................................... 5 NCSD Counseling Beliefs/Philosophy .............................................................................................................. 6 NCSD Program Goals, Curriculum, and Sample Action Plans .......................................................................... 6 Benefits of a School Counseling Program ........................................................................................................ 7 Counselor List .................................................................................................................................................. 9 Counselor Confidentiality .............................................................................................................................. 11 Definitions of Policy, Procedure, Practice ..................................................................................................... 11 Legal Issues for Counseling ............................................................................................................................ 12 NCSD Guidance and Counseling Program Overview (2008-2009) ................................................................ -

The Disabled People's Movement

The Disabled People’s Movement Book Four A Resource Pack for Local Groups of Disabled People Published by the BCODP The publication of this booklet was made possible by a grant from Charity Projects. First published in 1997 by The British Council of Organisations of Disabled People (BCODP). © BCODP All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publishers and copyright owners except for the quotation of brief passages by reviewers for the public press. Composed by Equal Ability for BCODP Printed by Bailey & Sons Ltd., Somercotes, Derbyshire About this booklet This booklet will not tell you how to run your group, or how to do things. It is designed to signpost you to the information that you need. It will: - Give you ideas about areas you need to think about - Point you in the direction of books and organisations that may help. Some of these books will tell you how to do things. - Fill-in some of the gaps that these books leave about being a group of disabled people. While we were working on these booklets, we talked to many local groups of disabled people. They told us about the hard work and determination you need to succeed. This Resource Pack has been written to help you find support and information so that your hard work does not go to waste. We hope that you will find these signposts get you where you want to go a bit more quickly than you would get there without them! Full details of all books and reference materials mentioned in this booklet is contained in Resource Booklet 6 Introduction What this booklet covers This booklet covers the Disabled People's Movement: • Disability and the Disabled People's Movement • The History of the Movement • International Issues • Integration and inclusion • Campaigning • Self-organisation • BCODP There are some good books that will help you understand more about these subjects.