Peacebuilding and the Politics of Writing (PDF, 238Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Narrative Report 2012

GgÁkarGnupléRBeQI Non-Timber Forest Products __________________________________________________ Annual Narrative Report for 2012 to ICCO & Kerk in Actie from NTFP Non-Timber Forest Products Organization Ban Lung, Ratanakiri Province, CAMBODIA Feb 28 2012 1 Contact addresses: Non-Timber Forest Products Organization (NTFP) Mr. Long Serey, Executive Director Email: [email protected] NTFP Main Office (Ratanakiri) NTFP Sub-office (Phnom Penh) Village 4, Sangkat Labanseak #16 Street 496 [Intersects St. 430] Banlung, Ratanakiri Province Sangkat Phsar Deom Skov CAMBODIA Khan Chamkarmorn Tel: (855) 75 974 039 Phnom Penh, CAMBODIA P.O. Box 89009 Tel: (855) 023 309 009 Web: www.ntfp-cambodia.org 2 Table of Contents Acronyms Executive summary 1. Overview of changes and challenges in the project/program context 1.1 Implications for implementation 2. Progress of the project (summary) ʹǤͳ ǯrograms and projects during 2012 2.2 Contextualized indicators and milestones 2.3 Other issues 2.4 Monitoring of progress by outputs and outcomes 3. Reflective analysis of implementation issues 3.1 Successful issue - personal and community perspectives on significant change 3.1.1 Account of Mr Bun Linn, a Kroeung ethnic 3.1.2 Account of Mr Dei Pheul, a Kawet ethnic 3.1.3 Account of Ms Seung Suth, a Tampuan ethnic 3.1.4 Account of Ms Thav Sin, a Tampuan ethnic 3.2 Unsuccessful issue (implementation partially done) 4. Lessons learned to date, challenges and solutions 4.1 Reference to KCB 4.2 Reference to youth (IYDP) 4.3 Reference to IPWP 4.4 Reference to CC 4.5 Reference to CF 4.6 Reference to CMLN 5. -

Ratanakiri, Cambodia*

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 47, No. 3, December 2009 Understanding Changes in Land and Forest Resource Management Systems: Ratanakiri, Cambodia* Jefferson FOX,** John B. VOGLER*** and Mark POFFENBERGER**** Abstract This paper draws on case studies from three communities in Ratanakiri to illustrate both the forces driving land-use and tenure change as well as how effective community stewardship can guide agricultural transi- tions. The study combines a time series of remotely sensed data from 1989 to 2006 to evaluate changes in land use, and relates this data to in-depth ground truth observations and social research from three villages. The methodology was designed to evaluate how indigenous communities who had historically managed forest lands as communal resources, are responding to market forces and pressures from land speculators. Krala Village received support from local non-government organizations (NGOs) to strengthen community, map its land, demarcate boundaries, strengthen resource use regulations, and develop land-use plans. The two other villages, Leu Khun and Tuy, each received successively less support from outside organizations for purposes of resource mapping and virtually no support for institutional strengthening. The remote sensing data indicates that in Krala, over the 16 year study period, protected forest areas remained virtually intact, while total forest cover declined at an annual rate of only 0.86% whereas in Leu Khun and Tuy the annual rates were 1.63 and 4.88% respectively. Keywords: land use, land cover, forest management, resource management systems, Cambodia I Introduction Over the past decade, Ratanakiri Province has experienced unprecedented changes in land use and tenure. This study analyzes remotely sensed images taken in 1989 and December 2006 to assess changes in vegetative cover in three areas near Banlung the provincial capital, and draws on in-depth case studies from three communities in the research area. -

Impacts of Economic Land Concessions on Project Target

Impacts of Economic Land Concessions on Project Target Communities Living Near Concession Areas in Virachey National Park and Lumphat Wildlife Sanctuary, Ratanakiri Province Impacts of Economic Land Concessions on Project Target Communities Living Near Concession Areas in Virachey National Park and Lumphat Wildlife Sanctuary, Ratanakiri Province Submitted by: Ngin Chanrith, Neth Baromey, and Heng Naret To: Save Cambodia’s Wildlife November 2016 Contact: Save Cambodia's Wildlife (SCW), E-Mail: [email protected] , Phone: +855 (0)23 882 035 #6Eo, St. 570, Sangkat Boeung Kak 2, Khan Tuol Kork, Phnom Penh, Cambodia www.facebook.com/SaveCambodiasWildlife, www.cambodiaswildlife.org Impacts of Economic Land Concessions on Project Target Communities Living Near Concession Areas in Virachey National Park and Lumphat Wildlife Sanctuary, Ratanakiri Province CONTENTS ACRONYMS i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ii CHAPTER: Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Backgrounds and Rationale …………………………………………………..………...1 1.2. Aim and Objectives …………………………………………………………..………...2 2. METHODOLOGY 2.1. Data Collection Methods…………………………………………………..…………..3 2.2. Sampling Techniques and Sampling Frames……………………………………..…….. 4 2.3. Data Analysis Methods………………………………………………………..………..5 2.4. Limitations of the Study…………………………………………………………..….....5 3. STATUS OF INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY LIVELIHOODS IN RATANAKIRI 3.1. Profile and Characteristics of Ratanakiri Province……………………………..……....6 3.2. Livelihood Vulnerability of Indigenous Communities…………………………..……....8 3.3. Capital Assets of Indigenous Community Livelihoods………………………..………17 4. ELCs AND IMPACTS ON INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY LIVELIHOODS 4.1. Status of Economic Land Concessions in Ratanakiri Province………………..……....27 4.2. Impacts of ELCs on Indigenous Communities and Their Areas…………………..…. 29 4.3. ELC-Community Conflicts and Existing Conflict Resolution Actors …………..…… 36 5. LIVELIHOOD INTERVENTION PROGRAMS OF CONCERNED STAKEHOLDERS 5.1. Community Perceptions of Current Livelihood Interventions Mechanisms….……. -

Download Publication

BASIN PROFILE OF THE LOWER SEKONG, SESAN AND SREPOK (3S) RIVERS IN CAMBODIA August 2013 MK3 Optimising cascades Paradis Someth, of hydropower Sochiva Chanthy, Chhorda Pen, Piseth Sean, BASIN PROFILE Leakhena Hang Authors Paradis Someth, Sochiva Chanthy, Chhorda Pen, Piseth Sean, Leakhena Hang Produced by Mekong Challenge Program for Water & Food Project 3 – Optimising cascades of hydropower for multiple use Led by ICEM – International Centre for Environmental Management Suggested citation Someth, P. et al. 2013. Basin Profile of the Lower Sekong, Sesan and Spreok (3S) Rivers in Cambodia. Project report: Challenge Program on Water & Food Mekong project MK3 “Optimizing the management of a cascade of reservoirs at the catchment level”. ICEM – International Centre for Environmental Management, Hanoi Vietnam, 2013 More information www.optimisingcascades.org | www.icem.com.au Image Cover image: High flows in Sesan river at Ta Veaeng (Photo Peter-John Meynell). Inside page: Sesan river near the border between Cambodia and Vietnam, a few kilometres below the proposed dam site of Sesan1/5 HPP (Photo Peter-John Meynell). Project Team Peter-John Meynell (Team Leader), Jeremy Carew-Reid, Peter Ward, Tarek Ketelsen, Matti Kummu, Timo Räsänen, Marko Keskinen, Eric Baran, Olivier Joffre, Simon Tilleard, Vikas Godara, Luke Taylor, Truong Hong, Tranh Thi Minh Hue, Paradis Someth, Chantha Sochiva, Khamfeuane Sioudom, Mai Ky Vinh, Tran Thanh Cong Copyright 2013 ICEM - International Centre for Environmental Management 6A Lane 49, Tô Ngoc Vân| Tay Ho, HA NOI | Socialist Republic of Viet Nam i MEKONG CPWF| Optimising cascades of hydropower (MK3) Basin Profile of the Lower Sekong, Sesan and Srepok (3s) Rivers in Cambodia TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................ -

Policy Making for Sustainable Development and the Yeak Laom Commune Protected Area

Policy Making for Sustainable Development and the Yeak Laom Commune Protected Area Consultant Report Kenneth G. Riebe International Development Research Centre of Canada and UNDP/CARERE-Ratanakiri CAMBODIA February 1999 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In a broad and general way this report covers over three years of work developing a sustainable development policy strategy for Northeast Cambodia. In a much more specific manner it deals with the experience of Yeak Laom Commune Protected Area, in Ratanakiri Province. Program activities took place both in Phnom Penh and Ratanakiri, with a fair amount of travel in between. I need to acknowledge a number of fellow travelers for their support, both personal and professional. Kep Chuktema and the rest of the Provincial Administration of Ratanakiri Province Andrew McNaughton Bill Herod Michael Barton Dominic Taylor-Hunt Ardhendu Chatterjee Jeremy Ironside Nhem Sovanna By Seng Leang Thomas deArth Jeffrey Himel Touch Nimith Cheam Sarim Chan Sophea Kham Huot Tonie Nooyens Ashish John Caroline McCausland Som Sochea Kong Sranos Bie Keng Byang Bep Bic Pleurt and the rest of the Committee and staff All the People of Yeak Laom Commune. Photos: Dominic Taylor-Hunt, Touch Nimith and the author. Cover Photo: Ethnic Tampuan Highlanders place traditional bamboo weaving and thatch roof on the Yeak Laom Lake Environmental and Cultural Centre. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY POLICY MAKING FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT AND THE YEAK LAOM COMMUNE PROTECTED AREA The pace at which Cambodia’s Northeast is being ‘developed’ is threatening to worsen an already weak position from which the indigenous Ethnic Highlanders or Chunchiets could gain from that development. The external pressures generated from immigration of lowlanders from other provinces and from Cambodian and foreign investment in land, for industrial agriculture crops such as oil palm, rubber, cassava, kapok, coffee, etc., and especially logging, are all contributing to the increasing disenfranchisement of the Highlanders. -

![[Partner Name and Country]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5309/partner-name-and-country-2065309.webp)

[Partner Name and Country]

Control and Prevention of Malaria (CAP-Malaria) Cambodia Semi-Annual Progress Report (October 1, 2014 to March 31, 2015) Last update April 30, 2015 Prepared by the CAP-Malaria Team EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 1 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 PROGRAM PERFORMANCE/ACHIEVEMENTS DURING REPORTING PERIOD ........... 5 2.1 Malaria Prevention ....................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.1 LLIN Distribution and Monitoring ............................................................................................................... 5 2.1.2 BCC Interventions/Services ........................................................................................................................ 6 2.1.3 Community Mobilization ............................................................................................................................ 8 2.1.4 Display IEC Materials and Printed Materials .............................................................................................. 8 2.2 Malaria diagnosis and treatment .................................................................................................................. 9 2.2.1 Training on RDT Use and Basic Microscopy ............................................................................................. -

Map of Cambodia

0 50 miles THAILAND LAOS The Dragon’s Tail 0 50 km Samrong Anlong Veng Cheom Ksan ODDAR MEANCHEY Siempang Tbeng Virachey National Park BANTEAY Meanchey MEANCHEY STUNG Banlung TRENG Poipet SIEM REAP PREAH VIHEAR g RATANAKKIRI n a o Sisophon Boeung Per k e Angkor Wat r Stung Treng Lumphat Phnom Wildlife Sanctuary e A M Malai t Siem Reap s e r Battambang o F Tonle g Sandan n PAILIN BATTAMBANG Sap a L KAMPONG THOM y e Pailin r MONDULKIRI Moung P KRATIE Roessei Kampong Thom Samlaut Kratie Sen Monorom Pursat Peam Koh Snar Kampong PURSAT Chhnang KAMPONG KAMPONG CHAM Snoul Ca CHHNANG Kampong Cham rd a Kang Meas Memot m o m KAMPONG Koh Kong M SPEU KANDAL o Phnom Penh u n Prey Veng KOH KONG ta PREY VIET NAM in Kampong Takhmao s VENG Speu SVAY RIENG Sre Ambel Neak Svay Rieng TAKEO Loeung KAMPOT Bavet Takeo PREAH SIHANOUK Bokor National capital Kampot M ek Provincial capital on Sihanoukville Kep g The Parrot’s (Kampong Som) KEP Beak Town, village Provincial border Major road Gulf of Thailand Rail Map of Cambodia. xvi 1 “Brother Number One”: Pol Pot, Cambodia’s Robespierre and the architect of the Khmer Rouge revolution, photographed shortly after taking power in Phnom Penh in April 1975. 2 Women toil on a communal worksite in Democratic Kampuchea. 3 Supporters of the Vietnamese-backed Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation celebrate the collapse of Democratic Kampuchea in Chhbar Ampov, Phnom Penh, on January 25, 1979. The sign in the photo reads, “Bravo, Cambodia is fully liberated!” 4 The new masters of Cambodia: Heng Samrin (center) and Pen Sovan (left) greet a state media delegation from the Mongolian People’s Republic at Pochentong International Airport on March 15, 1979. -

11925773 07.Pdf

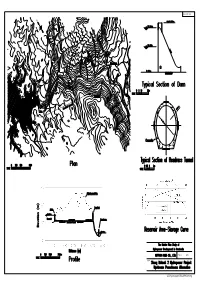

Final Report Appendix-B Results of Natural Environment Survey by Subcontractor APPENDIX-B RESULTS OF NATUAL ENVIRONMENT SURVEY BY SUBCONTRACTOR NATURAL ENVIRONMENT The rapid economic growth of Cambodia in recent years drives a huge demand for electricity. A power sector strategy 1999–2016 was formulated by the government in order to promote the development of renewable resources and reduce the dependency on imported fossil fuel. The government requested technical assistance from Japan to formulate a Master Plan Study of Hydropower Development in Cambodia. The objective of this paper is to survey the natural and social environment of 10 potential hydropower projects in Cambodia that can be grouped into six sites as listed below. This survey constitutes part of the Master Plan Study of Hydropower Development in Cambodia. The objective of the survey is to gather baseline information on the current conditions of the sites, which will be used as input for a review and prioritisation of the selected project sites. This report indicate the natural environment of the following projects on 6 basins. Original Site No. Name of Project Provice Protected Area (Abbreviation) 1 No. 12, 13 & 14 Prek Liang I, IA, II Ratanak Kiri Virachey National Park (VNP) 2 No. 7 & 8 Lower Se San II & Lower Stung Treng - Sre PokII 3 No. 29 Bokor Plateau Kampot Bokor National Park (BNP) 4 No. 22 Stung Kep II Koh Kong Southern Cardamom Protected Forest (SCPF) 5 No. 16 & 23 Middle and Upper Stung Koh Kong Central Cardamom Protected Forest Russey Chrum (CCPF) 6 No. 20 & 21 Stung Metoek II, III Pursat & Koh Phnom Samkos Wildlife Sanctuary Kong (PSWS) No. -

Cambodia Municipality and Province Investment Information

Cambodia Municipality and Province Investment Information 2013 Council for the Development of Cambodia MAP OF CAMBODIA Note: While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the information in this publication is accurate, Japan International Cooperation Agency does not accept any legal responsibility for the fortuitous loss or damages or consequences caused by any error in description of this publication, or accompanying with the distribution, contents or use of this publication. All rights are reserved to Japan International Cooperation Agency. The material in this publication is copyrighted. CONTENTS MAP OF CAMBODIA CONTENTS 1. Banteay Meanchey Province ......................................................................................................... 1 2. Battambang Province .................................................................................................................... 7 3. Kampong Cham Province ........................................................................................................... 13 4. Kampong Chhnang Province ..................................................................................................... 19 5. Kampong Speu Province ............................................................................................................. 25 6. Kampong Thom Province ........................................................................................................... 31 7. Kampot Province ........................................................................................................................ -

Land Acquisitions in Northeastern Cambodia: Space and Time Matters

Land grabbing, conflict and agrarian‐environmental transformations: perspectives from East and Southeast Asia An international academic conference 5‐6 June 2015, Chiang Mai University Conference Paper No. 24 Land Acquisitions in Northeastern Cambodia: Space and Time matters Christophe Gironde and Amaury Peeters May 2015 BICAS www.plaas.org.za/bicas www.iss.nl/bicas In collaboration with: Demeter (Droits et Egalite pour une Meilleure Economie de la Terre), Geneva Graduate Institute University of Amsterdam WOTRO/AISSR Project on Land Investments (Indonesia/Philippines) Université de Montréal – REINVENTERRA (Asia) Project Mekong Research Group, University of Sydney (AMRC) University of Wisconsin-Madison With funding support from: Land Acquisitions in Northeastern Cambodia: Space and Time matters by Christophe Gironde and Amaury Peeters Published by: BRICS Initiatives for Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS) Email: [email protected] Websites: www.plaas.org.za/bicas | www.iss.nl/bicas MOSAIC Research Project Website: www.iss.nl/mosaic Land Deal Politics Initiative (LDPI) Email: [email protected] Website: www.iss.nl/ldpi RCSD Chiang Mai University Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University Chiang Mai 50200 THAILAND Tel. 6653943595/6 | Fax. 6653893279 Email : [email protected] | Website : http://rcsd.soc.cmu.ac.th Transnational Institute PO Box 14656, 1001 LD Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tel: +31 20 662 66 08 | Fax: +31 20 675 71 76 Email: [email protected] | Website: www.tni.org May 2015 Published with financial support from Ford Foundation, Transnational Institute, NWO and DFID. Abstract Over the last decade, the highlands of Ratanakiri province in northeastern Cambodia have witnessed massive land acquisitions and profound land use changes, mostly from forest covers to rubber plantation, which has contributed to rapidly and profoundly transform the livelihoods of smallholders relying primarily on family-based farming. -

The Master Plan Study on Rural Electrification by Renewable Energy in the Kingdom of Cambodia

No. Ministry of Industry, Mines and Energy in the Kingdom of Cambodia THE MASTER PLAN STUDY ON RURAL ELECTRIFICATION BY RENEWABLE ENERGY IN THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME 5: APPENDICES June 2006 Japan International Cooperation Agency NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD., Tokyo ED JR KRI INTERNATIONAL CORP., Tokyo 06-082 Japan International Ministry of Industry, Mines and Cooperation Agency Energy in the Kingdom of Cambodia THE MASTER PLAN STUDY ON RURAL ELECTRIFICATION BY RENEWABLE ENERGY IN THE KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME 5 : APPENDICES June 2006 NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD., Tokyo KRI INTERNATIONAL CORP., Tokyo Final Report (Appendices) Abbreviations Abbreviations Abbreviation Description ADB Asian Development Bank Ah Ampere hour ASEAN Association of South East Asian Nations ATP Ability to Pay BCS Battery Charging Station CBO Community Based Organization CDC Council of Development for Cambodia CDM Clean Development Mechanism CEC Community Electricities Cambodia CF Community Forestry CFR Complementary Function to REF CIDA Canadian International Development Agency DAC Development Assistance Committee DIME Department of Industry, Mines and Energy DNA Designated National Authority EAC Electricity Authority of Cambodia EdC Electricite du Cambodge EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return ESA Energy Service Agent ESCO Energy Service Company EU European Union FIRR Financial Internal Rate of Return FS Feasibility Study GDP Gross Domestic Product GEF Global Environment Facility GHG Greenhouse Gas GIS Geographic -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Asian Adventures, 48 Blue 7 Massage (Phnom ATMs (automated-teller Penh), 85 machines), Laos, 202 Boat travel ARP, 43, 204 A Cambodia, 35, 37 Accommodations. See also Laos, 199, 200 Accommodations Index akeng Hill (Angkor), 114 Phnom Penh, 60–61 best, 4, 6 B Bamboo Train (Battambang), Sangker River (Battam- AIDS, 41 143 bang), 144 Airport (Sihanoukville), 164 Banlung, 148 Siem Reap, 94 Air travel Ban Phanom Weaving Sihanoukville, 162 Cambodia, 33, 35 Village, 280 Body Tune Spa (Siem Reap), Laos, 196, 198 Banteay Kdei (Angkor), 121 125 All Lao Services (Luang Banteay Srei, 121–122 Bokor Mountain, 172 Prabang), 258 Baphuon (Angkor), 118 Bokor Palace Casino and All Lao Travel Service (Luang Battambang, 3, 133–145 Resort (Kampot), 172–173 Prabang), 282 accommodations, 138–140 The Bolaven Plateau, 319–320 Ambre (Phnom Penh), 87 arriving in, 133–134 Bonkors (Kampot), 172 American Express, 91, 239 ATMs, 137 Bonn Chroat Preah Nongkoal Amret Spa (Phnom Penh), 85 attractions, 142–144 (Royal Plowing Angkor Balloon, 119 banks and currency Ceremony), 30 Angkor National Museum exchange, 137 Bonn Pchum Ben (Siem Reap), 124 business hours, 137 (Cambodia), 31 Angkor Night Market, 128 doctors and hospitals, 137 Books, recommended Angkor Thom, 116 food stalls, 142 Cambodia, 25 Angkor Village (Siem Reap), getting around, 136–137 Laos, 189 12, 93, 131 Internet access, 137 Boom-Boom Records dance performances, 129 nightlife, 144–145 (Sihanoukville), 163 guidelines for visiting, 113 post office, 137 Boom Boom Room (Phnom sunrises and sunsets, 119 restaurants, 140–142 Penh), 87–88 temple complex, 112–121 shopping, 144 Bopha Penh Titanic Restau- Angkor Wat, 7, 93, 113–114.